As wildfires intensify, new housing developments put Americans closer to danger

As wildfires intensify, new housing developments put Americans closer to danger

When human development butts up against previously undeveloped wild land, this new region is called the wildland-urban interface, and roughly one-third of the U.S. population lives in it.

These areas are often on the outskirts of desirable metropolitan regions. They appeal to prospective homeowners because they are close to nature and more affordable than urban housing; however, this proximity also puts residents—and their homes—at an increased risk of wildfires. By settling along the edges of forests, grasslands, and scrublands near combustible vegetation, communities increase their risk of exposure and loss to fires. Similarly, as more humans occupy these once-wild areas, they're increasingly likely to start fires as well: According to the U.S. Fire Association, 89% of all wildfires nationwide are caused by humans.

Some fires, such as controlled burns set by professionals or those ignited by lightning strikes, are essential to maintaining healthy ecosystems. Much of America's landscape depends on fires to renew habitats that support plant and animal populations by reducing overgrowth of weak or diseased trees, clearing debris, and enriching the soil with nutrients—literally clearing the way for new generations of healthy species to thrive.

Human-ignited wildfires, particularly in the WUI, behave differently; they are more frequent and destructive. The Federal Emergency Management Agency cites rising housing costs, climate change, reduced land management practices, and lax housing development regulations as contributing factors to the growth of the WUI and the fires that ravage it.

In the last 10 years, more than 51,000 structures have been destroyed and hundreds of lives lost due to wildfires. Still, the WUI shows no signs of shrinking. It grew by 12.6 million more houses and 25 million more people between 1990-2010, according to a 2018 analysis. Without addressing the causes of WUI expansion, wildfires will continue to pose a significant threat to the nearly 99 million Americans living in these regions.

Stacker examined the expanding boundaries of the wildland-urban interface and what it means for residents living with already-intensifying wildfires, citing data from the Spatial Analysis For Conservation and Sustainability Lab at the University of Wisconsin Madison, satellite imagery, and the National Interagency Fire Center.

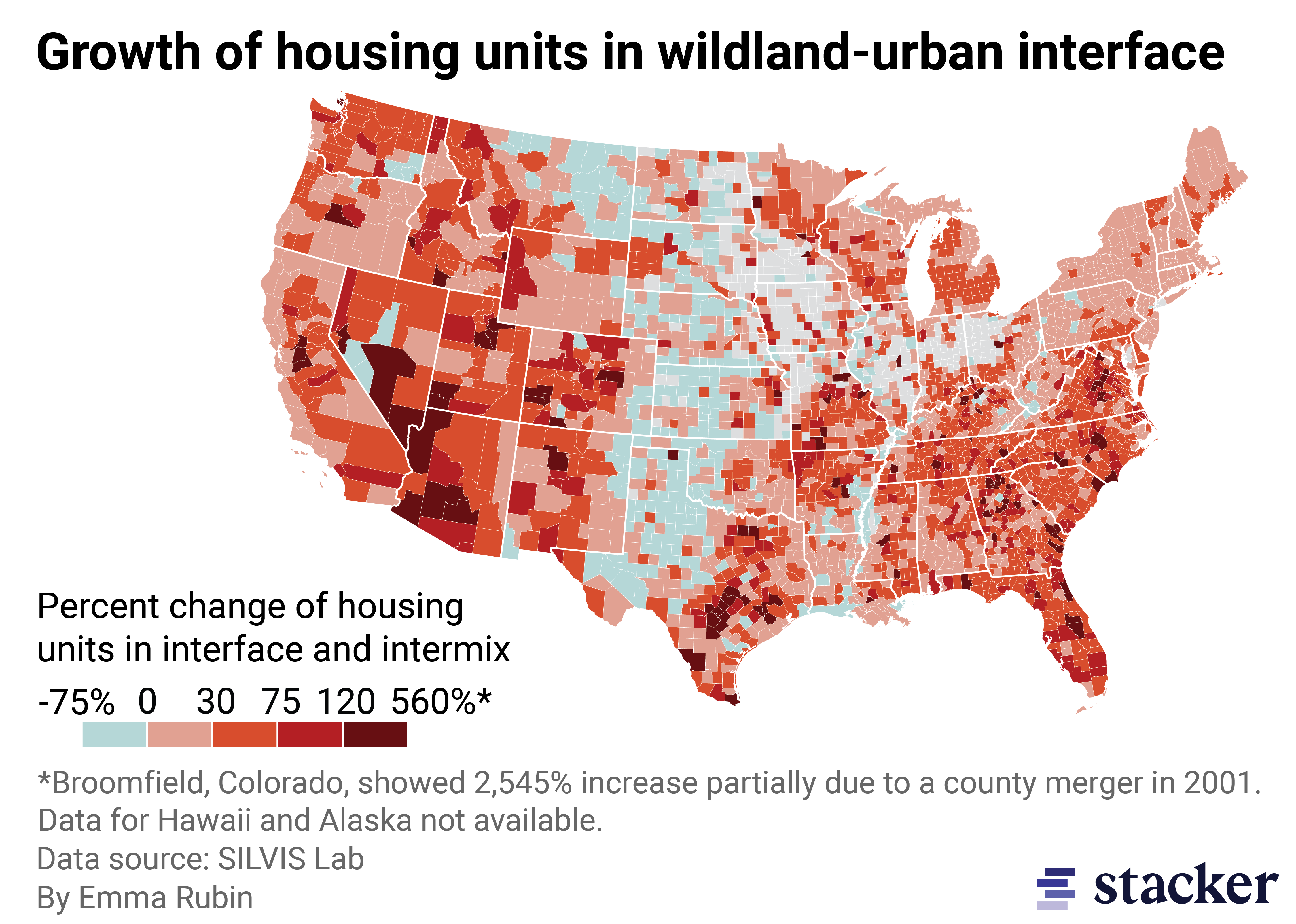

Between 1990 and 2010, the wildland-urban interface grew 33%

The growth of the WUI comes from the introduction of housing in what was previously wild land. A forest without the presence of housing is wild land. But when a property is constructed at the edge of the forest, that land becomes part of the WUI. The WUI now occupies more than 190 million acres across the U.S.—a 33% increase in physical space in just two decades, according to a June 2022 FEMA report. This translates to roughly 46 million properties, valued at $1.3 trillion, at risk of wildfire damage. Climate scientists have also discovered that the population in WUI regions considered to be at the highest risk of wildfires has grown by 160%, from 1 million to 2.6 million residents, in the same time frame.

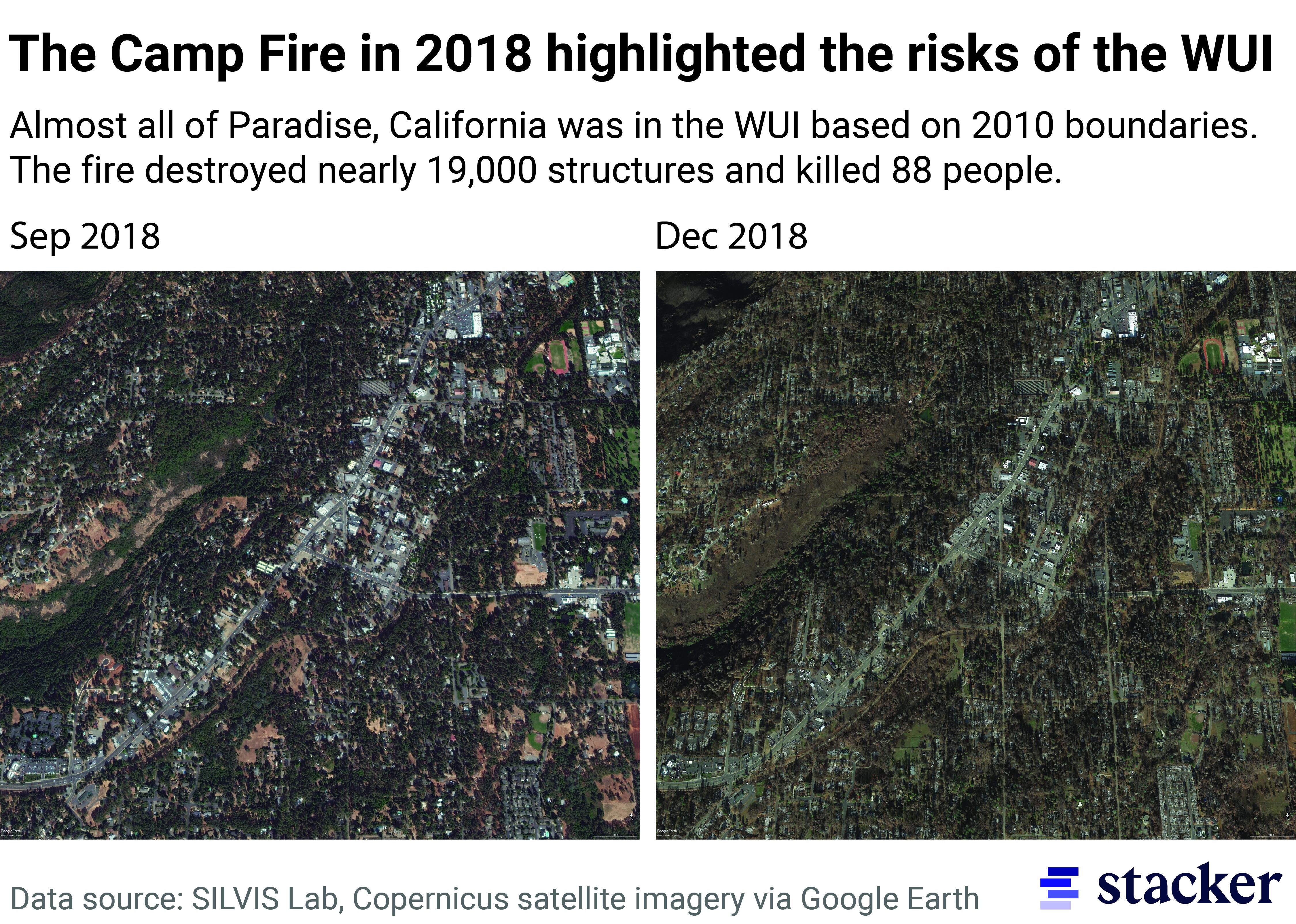

When fires break out in the WUI, their impacts can be devastating

In wildfire-prone regions, fuel breaks are built as a way to allow firefighters to control a fire. These wide tracts of modified land are designed to slow the burn and reduce the type of vegetation that fuels it. But miles of fuel breaks could not control California's 2018 Camp Fire. Ignited by a faulty Pacific Gas and Electricity power line, the fire was exacerbated by hot, dry, windy conditions that turned vegetation into tinder. High winds sent burning embers sailing over fuel breaks making its spread uncontrollable. The Camp Fire was the most destructive blaze in California's history by a hefty margin, destroying nearly 19,000 structures. The second most destructive fire—the 2017 Tubbs fire in Napa and Sonoma—destroyed roughly 5,600 structures. Just two years after the Camp Fire, the nearby town of Paradise was the fastest-growing city in California based on new housing production reports.

Greater population in WUI can also contribute to higher risk of human-caused wildfires

Because humans cause about 89% of all wildfires are caused by humans, nearly all wildfires that threaten homes can be attributed to humans. Unattended campfires, discarded cigarettes, electrical malfunctions, and even the occasional gender reveal stunt can all lead to devastating fires. These types of fires are far more destructive than those that occur naturally, not because they are chemically any different, but because weather conditions and the vegetative makeup of the WUI create an environment where fires can thrive. When seasonal lightning strikes ignite a fire in the middle of a dense, fire-adapted forest, that fire burns in a controlled and expected way, typically far away from people. When a spark from a faulty power line that services a community in the WUI ignites a fire at the forest's edge on a dry, windy day, the burn can quickly get out of control. Using satellite data, researchers from the University of California found that human-caused fires burned twice as fast and destroyed double or triple the number of trees lost to fires caused by lightning strikes.

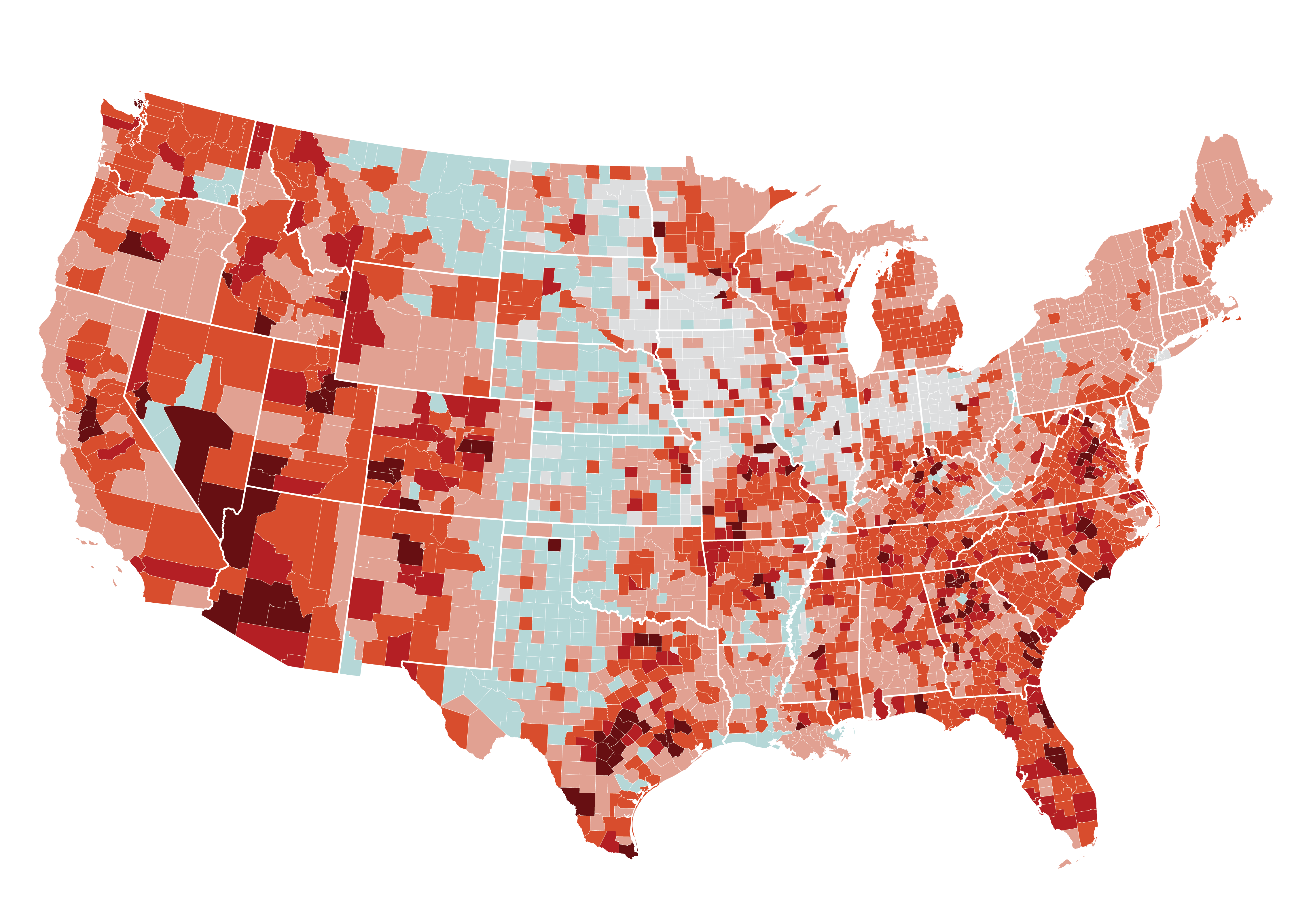

Nationally, the number of housing units in the WUI grew 41% between 1990-2010

Many people living in wildfire-prone regions may have purchased homes without knowing the full extent of the risk they have assumed. Home sellers in all but two states—California and Oregon—are not required to disclose wildfire risk to potential buyers, and even when it is provided, the language is non-specific and technical. Oregon's disclosure, for example, only indicates if a property is within a "forestland-urban interface," with no explicit mention of wildfires or more colloquial terminology that would signal danger. In recent years, online real estate brokers like Realtor.com and Redfin began including property risk assessments in their listings.

New construction in the wildland-urban interface is also highly unregulated and attractive for people who can't afford to buy or build in nearby cities. Local governments are often incentivized to approve more housing developments despite the risks, in order to reap certain financial benefits such as increased property taxes. Since 1991, California has required that all new structures in the WUI be built with noncombustible materials. However, there are no programs to retrofit old homes, like those that exist for flood and earthquake protection, for fire risk.

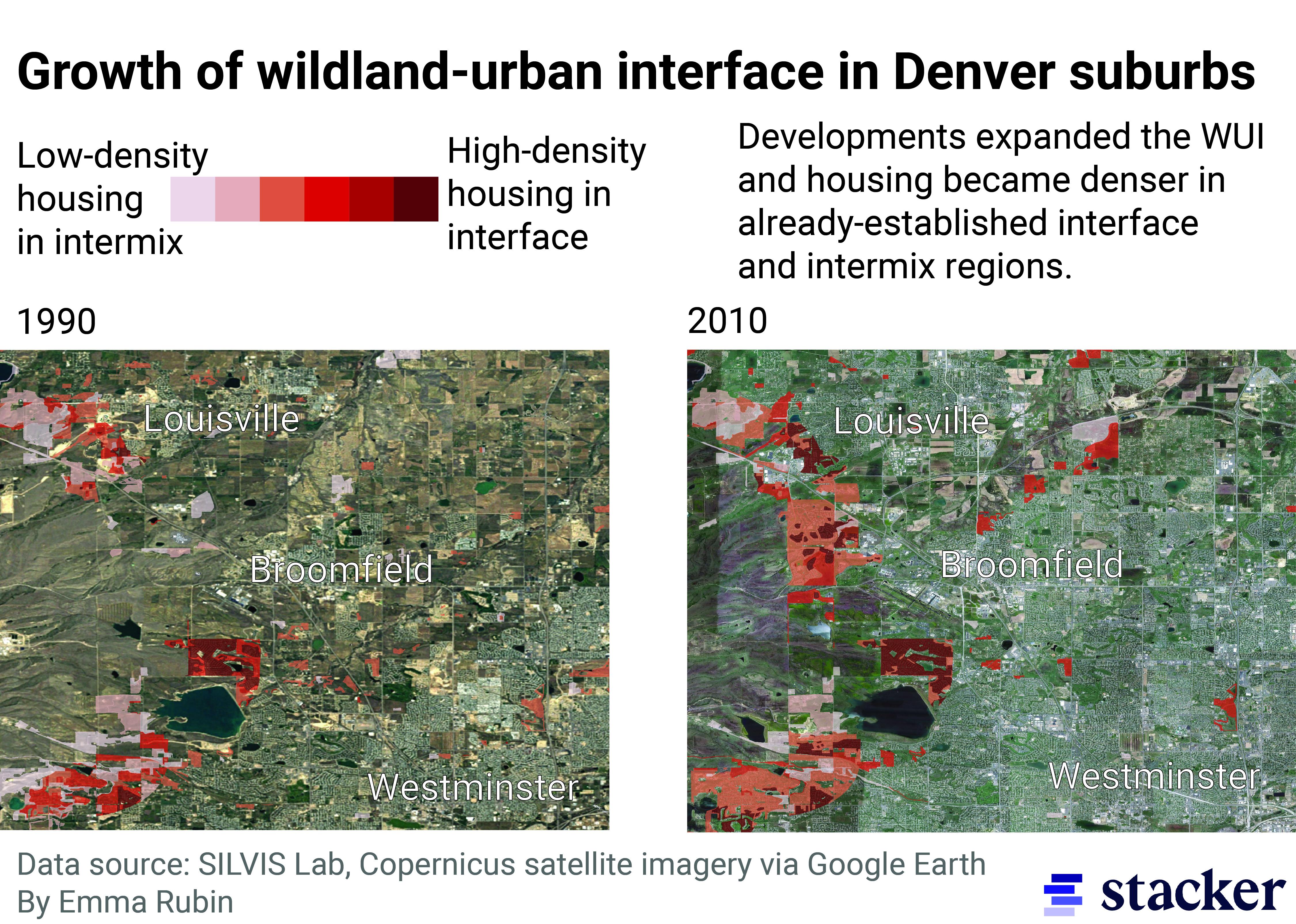

Sprawl of growing metropolitan areas like Denver contributed to the expansion of the WUI

Unaffordable housing in cities pushes people to buy or build in more remote areas. According to a market report by First American Title, which uses data provided by real estate app REcolorado, median home prices in Denver have risen from just over $215,000 in 2009 to approximately $575,000 as of Q1 2022. The Denver Metro Association of Realtors pegs that median figure at an even higher $580,000 as of September 2022. Median rent prices have likewise gone up by 77%, according to data from the Apartment Association of Metro Denver. As America's population center moves westward and housing prices remain high, people will continue to settle in more affordable ex-urban regions like Broomfield County. Situated between Denver and Boulder, Broomfield county grew from 62 units to 1,640 units between 1990-2010. It is important to note that Broomfield was incorporated in 2001 and absorbed properties from several surrounding counties, so this growth does not totally reflect new housing. Still, these homes exist in a region highly prone to wildfires and represent the danger of population shifts to the WUI.