The numbers behind baseball's triple play

Four innings into what was otherwise an unremarkable July game in 1990, the Minnesota Twins did the improbable by getting three Boston Red Sox out in a single play. It was the first triple play of the entire 1990 season, and the first time the ballclub had turned such a play in nearly two years. Four innings later, the Twins did the seemingly impossible: their defense turned another triple play. It was the first (and still only) time in Major League Baseball history that a team turned two triple plays in a single game.

When you dig into the numbers, Minnesota's feat becomes even more impressive. In almost 150 years of professional baseball, there have only been 730 triple plays. That equates to just under five per season, or one for roughly every 489 games. The Twins pulled off two within four innings of each other. A Rhode Island College professor estimated for the Boston Globe that the odds of such an event happening is about 370,000 to 1, or once every 175 years. Adding to the rarity of the accomplishment: Minnesota wouldn't turn another triple play until almost 16 years later.

Because triple plays are so scarce, Stacker wanted to uncover the numbers behind this elusive game changer. Using data from the Society for American Baseball Research, Stacker analyzed all 730 triple plays that have occurred in the major leagues over the past 146 years (as of July 2022). The findings are ahead.

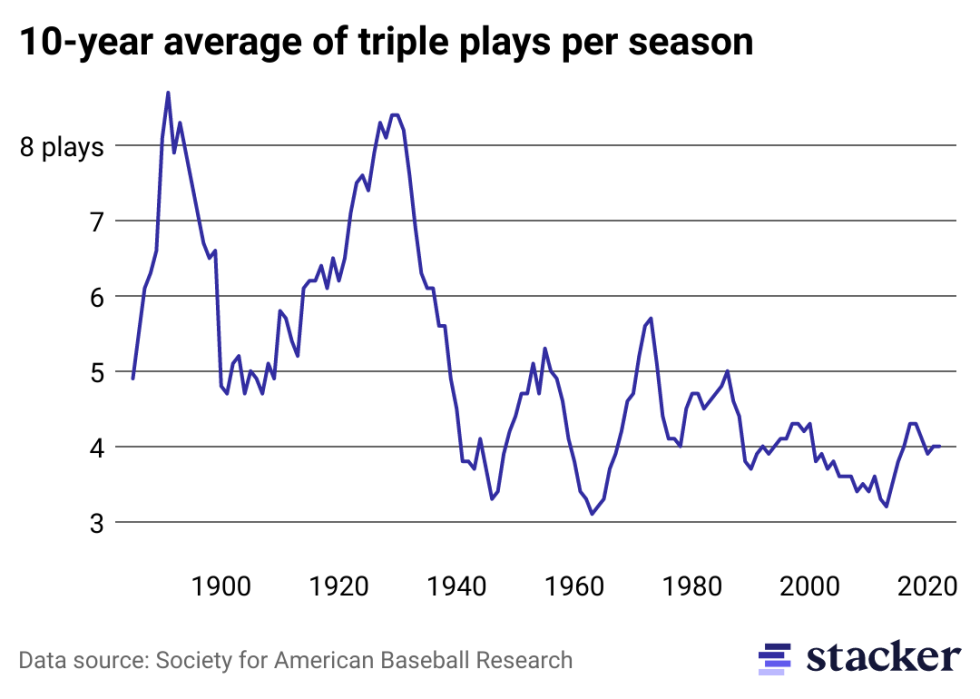

Triple plays have become rarer

During the dead ball era of the early 1900s, the average number of triple plays per season reached a number as low as 4.7 over 10 years. That rate spiked to above 8 in the late 1920s. Since a high of 8.4 triple plays per season over 10 years in 1929 and 1930, the rate shrank and has frequently remained below even dead ball era averages. The 10-year average currently sits at around 4.0 per season.

The rate of triple plays appears roughly correlated to offensive production. Throughout the years, as the rate of balls-in-play changes, so too does the rate of triple plays. The dead ball era—well known for its meager offensive numbers—saw fewer triple plays and balls-in-play. Then in the 1920s, balls-in-play and triple play frequencies shot up, as offense ruled the day. Ever since that initial post-dead ball era burst, the rates have generally decreased for both stats.

While the triple play is an execution on defense, its correlation to offensive production makes sense. A triple play requires at least two players to reach base. This means that if players are more unlikely to reach base, the chances of a triple play decrease. Because batters are putting fewer balls in play than they were 90 years ago, there are fewer chances for triple plays.

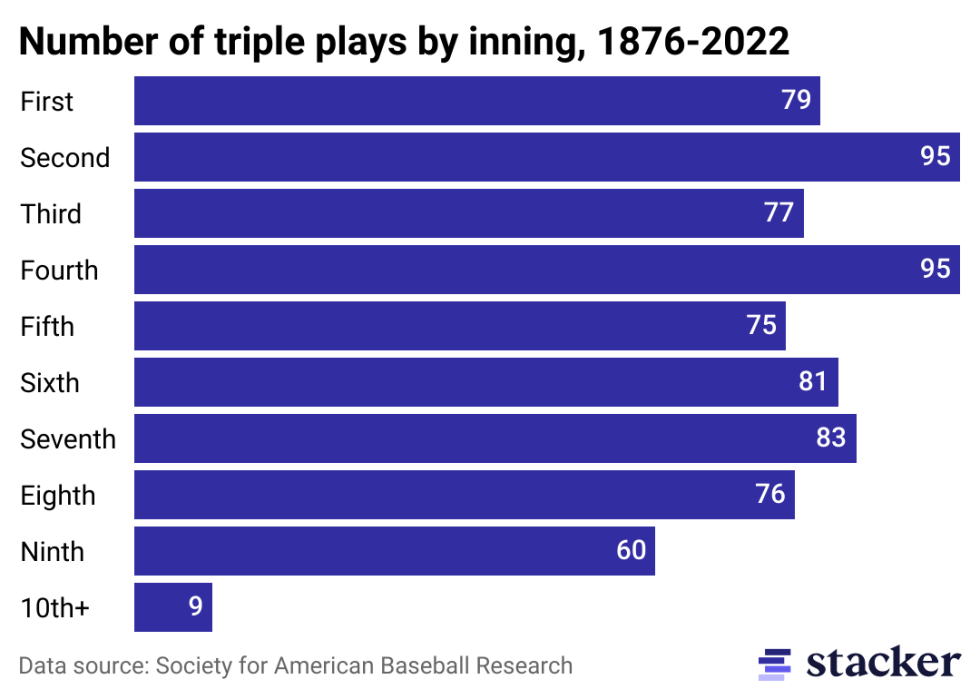

2nd, 4th innings are triple play hot spots

The rate of triple plays in each regulation inning is roughly similar, save for three outliers. The ninth inning is home to the fewest triple plays in history, which makes sense because the game can end without reaching the bottom of the ninth, making the final inning shorter on average than the preceding eight stanzas.

The other two outliers are a bit more complex. Both the second and fourth innings have had 95 triple plays throughout history. Ignoring the ninth inning because it can last half as long, 95 works out to roughly 1.5 standard deviations above the 82.6 average of the first eight innings. What gives?

A working theory revolves around the batting order. In the first and second inning, the batters most likely to encounter a triple play scenario will be the third and fourth hitters, who are usually solid at the plate and pick up more RBIs than other positions in the batting order. The second and third innings, meanwhile, are often reserved for the back half of the order. As such, those innings more frequently see weaker hitters, who may be more likely to hit into a triple play opportunity.

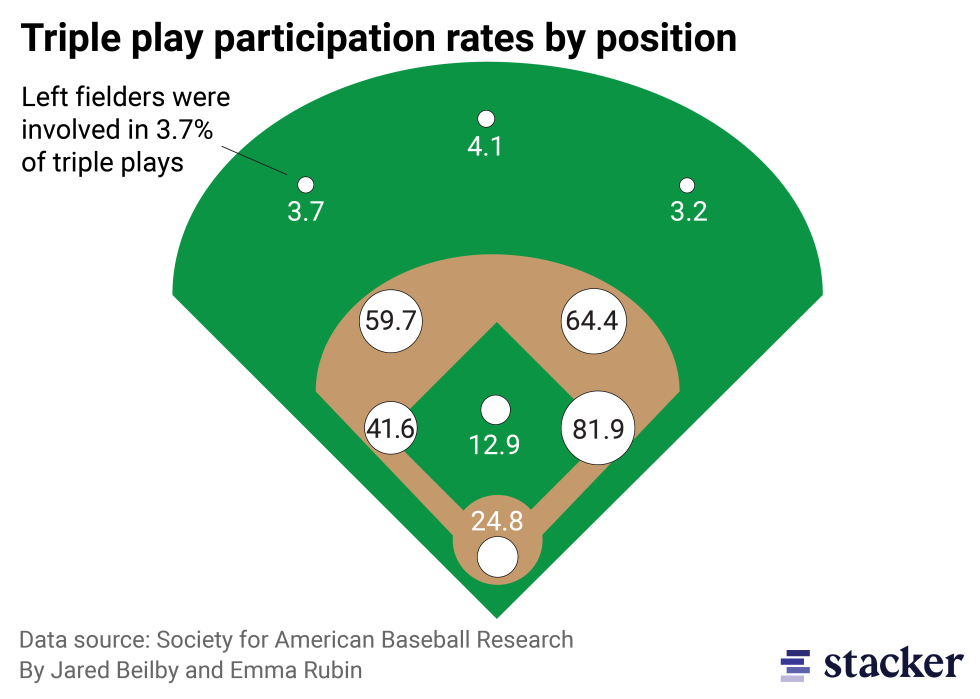

First basemen participate in over 80% of triple plays

An overwhelming number of triple plays involve the first basemen—nearly 82%. This is wholly unsurprising, because first base is in the most prominent position to get either the batter or the trailing base runner out. The other infield positions follow accordingly, with second base turning 64.4% of triple plays, shortstop 59.7%, and third base 41.6%.

The outfield, meanwhile, is largely absent from triple plays. In total, 10.8% of triple plays involve outfielders. The highest participation rate comes from center field, which also happens to be the only outfield position to turn an unassisted triple play.

When looking at how triple plays are scored, 5-4-3 (third base to second to first) has occurred 13.6% of the time, making it the most common type of triple play. In total, triple plays have been scored 243 different ways, with 174 occurring just once.

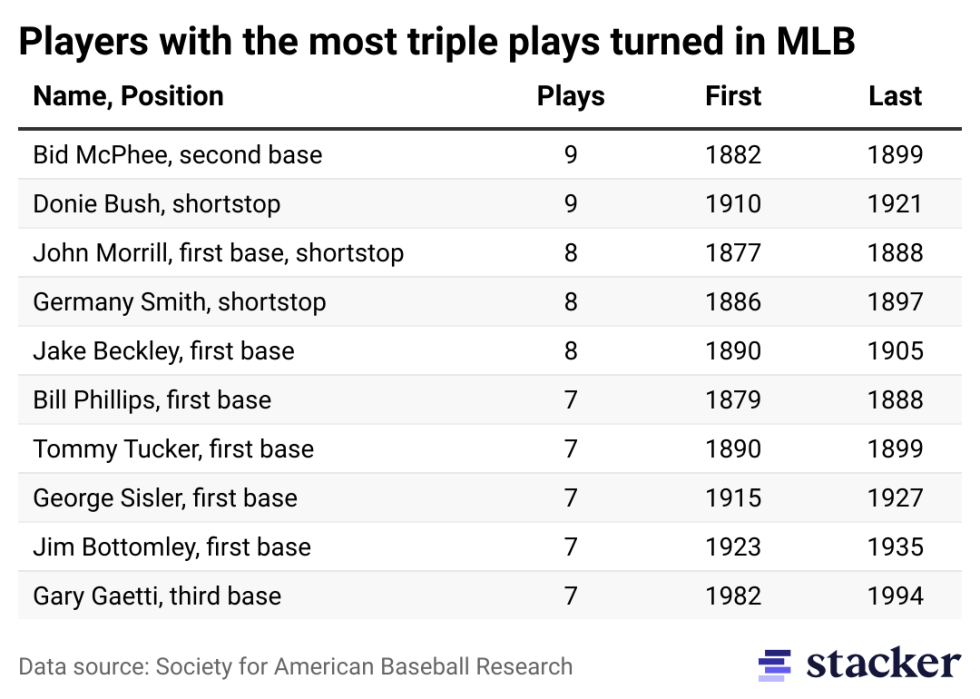

No player has been involved in turning more than 9 triple plays

Based on the data already uncovered, the all-time list of players who have participated in turning the most triple plays is unsurprising—most played 80-plus years ago, and first basemen make up the bulk of positions represented.

The all-time record is shared by two players: Bid McPhee and Donie Bush. McPhee played second base while spending his entire 18-year career in Cincinnati. Bush, meanwhile, was a longtime Detroit Tigers shortstop, who went on to have a career as a manager.

Gary Gaetti is perhaps the biggest oddity on this list. Not only is he the only third baseman to participate in seven or more triple plays, he's also the only player to be active in the past 30 years. On top of that, two of Gaetti's triple plays came in that already-mentioned double triple play game by the Minnesota Twins.

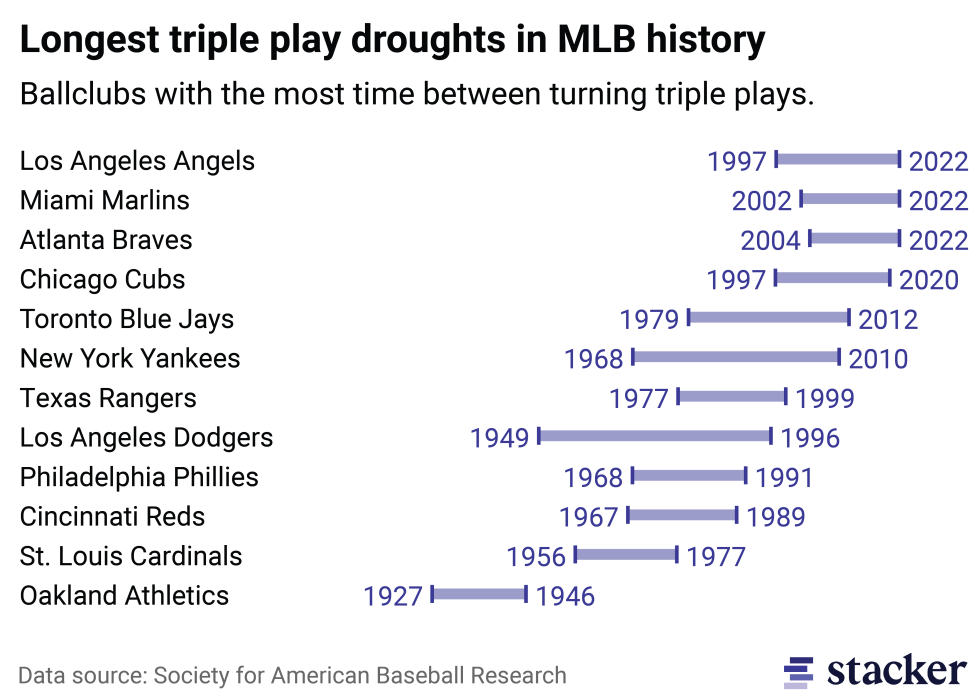

The longest triple play drought for a team lasted over 47 years

While the Minnesota Twins may have the shortest time in between triple plays, several ballclubs have experienced decades-long droughts.

The record for the longest drought in between triple plays goes to the Brooklyn/Los Angeles Dodgers. Brooklyn turned a triple play in April 1949—one which involved Hall of Famer Jackie Robinson—and didn't pull off another one before moving west in 1958. It wouldn't be until June 1996 that the drought ended, after a 2,700-mile move and the passage of 47 years. In a strange coincidence, the Dodgers stung the Braves franchise with both those triple plays—the first while the Braves were in Boston, and then again after the Braves moved to Atlanta.

Other teams with monstrous droughts include the New York Yankees (42 years between 1968 and 2010) and the Toronto Blue Jays (33 years between 1979 and 2012). Three long droughts are currently active, the longest being held by the Los Angeles Angels, a franchise that last turned a triple play in 1997. Maybe there's just something about Southern California?

All told, the rarity of triple plays means 47-year droughts or turning two in one game are statistical oddities with little to no explanation. It's nearly impossible to predict when the next one will occur. And, perhaps, that's part of what makes the triple play so special.