History of workers' strikes in America

History of workers' strikes in America

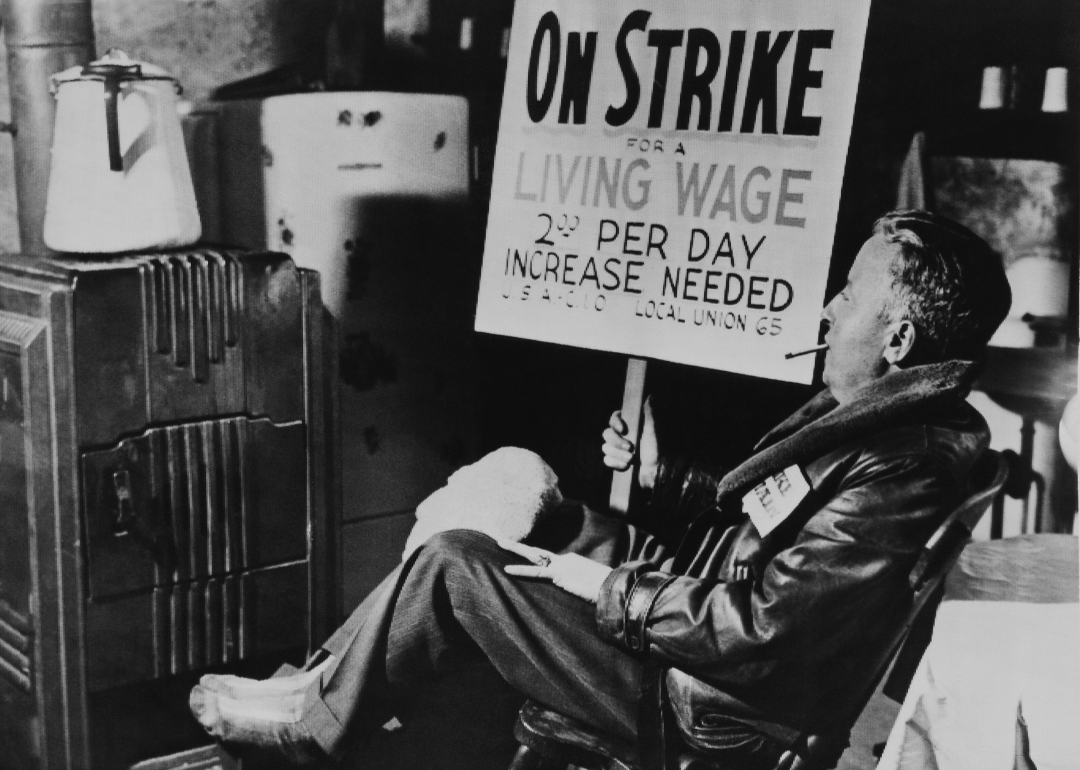

Before the U.S. was even a nation, labor strikes drove significant social and economic change. From the founding of the first major U.S. labor union, the Knights of Labor, to the development of the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), labor unions have helped employees stand up to the companies they work for in order to secure higher wages, safer working conditions, and bigger benefits. Although the frequency of strikes and positive outcomes have fluctuated over the years, walkouts are still vehicles through which American workers can try to pressure management into offering better pay rates and improvements in working environments.

Some periods of U.S. history saw higher incidents of labor stoppages than others, such as the years directly following World War I and World War II. Strikes in the U.S. became more prevalent during these periods than in other times, with wages and union recognition typically at the heart of the labor conflicts that arose in industries like mining and automobiles.

The Milwaukee Bucks' decision to stay off the basketball court on Aug. 26 showed a new kind of strike—a kind that goes beyond withholding labor to win concessions from an employer. This strike, the Bucks said in a statement from their locker room, was to demand action from Wisconsin lawmakers in response to the police shooting of Jacob Blake, a Black father shot in front of his children in Kenosha, Wisconsin. "Despite the overwhelming plea for change," the Bucks' statement read, "there has been no action, so our focus today cannot be on basketball."

Strikes aren't a thing of the past. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that 20 major labor strikes occurred in 2018 and 25 occurred in 2019. Most of these strikes involved workers in the education, health care, and social service sectors. 2020 has seen a handful of major labor strikes, in addition to strike threats from teachers unions, as in Chicago and New York City, in response to school reopening plans during the pandemic.

Funding for American public schools and compensation for teachers have been long-standing issues, as is apparent from the string of teachers' strikes throughout the decades. 2018 and 2019 saw a surge of teacher walkouts, starting with the West Virginia teachers' strike in 2018, in which 20,000 public school professionals demanded better pay and more affordable health care. Teachers in Arizona, Colorado, California, and other states followed suit, all fighting for higher wages. In 2019, L.A. teachers went on strike for a week and Chicago teachers went on strike for 11 days.

Read on to learn about some of the largest and most important labor strikes in American history, from the 1619 Jamestown Polish craftsmen strike to 21st-century strikes in the automotive, communications, and education fields. Information is compiled from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, publications like The Wall Street Journal and Fortune, as well as the AFL-CIO.

You may also like: 30 victories for workers' rights won by organized labor over the years

1619 Jamestown Polish craftsmen strike

In the first recorded strike in pre-revolutionary American history, Polish glassmakers and producers of pitch, tar, and turpentine for ship-building refused to continue working for the British Virginia Company until granted the right to vote in the seminal election for the Virginia House of Burgesses. Colonists had hired the Polish workers to come to Jamestown in order to manufacture items essential for the colony's economy—however, only those of English origin had the right to vote in elections at the time. The strike forced the company's hand, and the workers were granted full voting rights.

1661 indentured servants' plot

Isaac Friend and William Clutton led this indentured servants' strike in York County, Va., because of sub-par food rationing; some were given only corn to eat and water to drink. The uprising was largely unsuccessful. Subsequent laws were passed restricting servants' rights, permitting the brutal treatment of slaves, and advising masters to keep their servants under close watch. The revolt was followed by other sizeable uprisings, such as the 1663 rebellion against the governor of Gloucester County.

1774 ironworks' strike

Carpenters of the New Jersey Hibernia Iron Works were some of the first American building trades workers. Building trades unions played major roles in New Jersey trade federations that formed in the mid-1800s, like the New Jersey State Federation of Labor that expanded into the state's American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations. The New Jersey Building and Construction Trades Council and its associated union helmed the struggle for the eight-hour workday, higher wages, safer working environments, and stable pension plans.

1786 printers' strike

In the first recorded strike for higher pay in U.S. history, Philadelphia printers organized this work stoppage to demand an increase from 35 shillings a week to $6 a week. The strike met with success and led to similar wage-related disputes in Philadelphia, such as the 1806 strike of the Cordwainers, the first union to be charged with a criminal scheme.

1791 carpenters' strike

This carpenters' strike, also in Philadelphia, pushed for the 10-hour workday and was the first official building trades' strike in the U.S. The action succeeded and marks the first time a local union engaged in collective bargaining. As unions started to gain traction across the U.S., however, employers started pushing back. That led to more trade-centric upheavals, such as the 1824 textile strike.

1834 Lowell Mill women's strike

In the face of 13-hour work days and wage cuts, the women who ran Lowell Mill in Massachusetts protested for the reinstatement of their original pay and rallied women from other mills to join them in the fight. Their employers shut down the strike and sent the women back to work. Although these mill workers' efforts sparked future political uprisings in the form of the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association, which sought to establish 10-hour workdays, their fight for social justice was slow to bring substantial change. Case in point: New Hampshire passed the 10-hour workday law in 1847, but employers were not required to enforce it.

1873 coal miners' strike

A 20% wage cut was at the heart of this coal miners' strike in the northeastern valleys of Ohio and Pennsylvania. Miners demanded a small pay increase per ton of coal, but their efforts ultimately failed. With thousands of miners on strike, mine owners hired African-American and Italian replacement workers, which sparked a violent backlash from the strikers. The employers' use of immigrant substitute workers meant that the miners were unable to successfully organize.

1877 Great Railroad Strike

When the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad cut workers' pay twice in the previous year, their employees halted the running of trains until their most recent pay cut was reversed. After the West Virginia government attempted to restore order by sending in militia troops, the strike spread to Baltimore, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, and Chicago. In some cities, strikers became violent and destroyed railroad property. The strike ended primarily because of government and militia intervention, and the B&O Railroad hiring strikebreakers.

1881 Atlanta's washerwomen strike

Jim Crow laws were in full force in America in the late 1800s, but this didn't prevent a group of African-American washerwomen in Atlanta known as the Washing Society from banding together to insist on higher wages and workplace autonomy. In the face of disapproval from the press and arrests of protest leaders, this group of laundry maids addressed the mayor of Atlanta, demanding full control over the city's washing business in exchange for a $25 annual licensing fee. The city ultimately agreed to this condition, and the Washing Society paved the way for improvements in labor conditions in other Atlanta industries.

1886 Great Southwest Railroad Strike

In this strike involving over 200,000 workers, railroad employees in five states rose up against the Union Pacific and Missouri Pacific Railroads, owned by Jay Gould. They revolted on the grounds that a worker was fired "without due notice and investigation," as per the agreement between the then Knights of Labor and the Union Pacific. Gould hired strikebreakers to keep the railroads running, and, ultimately, the Knights of Labor disintegrated. But shortly thereafter Samuel Gompers and Peter McGuire founded the American Federation of Labor.

1887 sugar cane workers' strike

African-American sugar cane workers in Louisiana faced excruciating working conditions and extremely low pay: They earned about $13 a month paid in scrip, a coupon only valid at the plantation owner's store where prices were marked up. Workers were more often than not indebted to planters. Sugar cane workers rose up against plantations and demanded discontinuation of scrip payments, a daily pay increase, and a payday twice a month. The Louisiana Sugar Producers' Association refused these demands, leading to one of the bloodiest labor disputes in U.S. history—the Thibodaux massacre, where government militia attacked and killed black sugar workers who had been evicted from plantations.

1891 cotton pickers' strike

In September of 1891, a group of black sharecroppers in Lee County, Ark., possibly associated with the Colored Farmers' Alliance, rebelled against cotton plantation owners in demand of higher pay. However, the strike was largely unsuccessful; a white-led mob shut down the revolt and killed at least a dozen black cotton pickers. The severity of the backlash from this strike served as something of a precursor of future landowner retaliation against African-American labor disputes, such as the 1919 Elaine massacre.

1892 Homestead steel strike

In one of the most pivotal disputes in U.S. labor history skilled, steelworkers rose up against the Carnegie Steel Corporation in response to improved steel-making technologies and the subsequent mass hiring of unskilled workers and sliding scale wages. The Amalgamated Association of Iron Steel Workers organized this strike, making it one of the first highly organized and well-led labor revolt in American history. Carnegie Steel ultimately refused to recognize the union, and American steelworkers (and those in other heavy industries) were unable to gain recognition for collective bargaining until the 1930s.

1894 Cripple Creek miners' strike

When the Panic of 1893 caused deflation of the price of silver and an influx of silver miners began working in gold mines, the pay of gold miners dropped and they lashed out against their employers. Leaders of the Free Coinage Union teamed up with the Western Federation of Miners demanding $3 per eight-hour work day instead of the proposed $2.50. Ultimately, the union won, which led to the organizing of other workers, as well as the growth of the WFM in the years following the strike.

1899 newsboys' strike

When the Spanish-American War led to an increase in newspaper sales, some publishers raised the bulk price of 100 newspapers from 50 cents to 60 cents. As a result, newsboys in Long Island City, N.Y., began the strike against Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst, publishers of the New York World and the New York Journal, respectively. More strikers rose up in other parts of New York City. The demonstrations ended when Pulitzer and Hearst proposed to keep the price of 100 newspapers at 60 cents, but would buy back papers the newsboys couldn't sell. DC Comics fictionalized the newsboys in the 1942 comic "Newsboy Legion," and Disney created the musical movie "Newsies," retelling the story of the strike.

1907 San Francisco streetcar strike

In one of the most violent U.S. streetcar strikes in the first third of the 20th century, drivers walked off the job, demanding eight-hour workdays and wages of $3 a day. This did not bode well for the city of San Francisco, which relied on its trolley cars to function. When the president of United Railroads called for 400 strikebreakers, strikers took to the streets. They attacked strikebreakers on Tuesday, May 7, in what the San Francisco Chronicle described as “Bloody Tuesday.” After 31 deaths the strike ultimately failed and the streetcar union was disbanded.

1912 Lawrence textile strike

In what was also known as the Bread and Roses Strike, members of the Industrial Workers of the World rose up against owners of the Everett Mill in Lawrence, Mass., in response to a decrease in weekly hours and a 32 cent per week pay-cut. In the early 1900s, textile workers survived on very little to eat and typically died before the age of 40. Workers of dozens of nationalities, many of whom were women, stood at the heart of this strike. After President William Howard Taft called for an investigation into mill working conditions, owners awarded workers a 15% wage increase and higher overtime pay. The strike paved the way for hundreds of thousands of New England textile workers and those in other industries to receive better wages.

1919 Great Steel Strike

On the heels of tapering wartime inflation, American steel workers experienced low wages, long hours, and poor working conditions. The AFL ground half the steel industry to a halt in this strike of 35,000 workers, demanding an eight-hour workday, better pay, and union recognition. Steel companies pushed back hard, portraying steelworkers, a workforce largely composed of immigrants, as radical threats to American society. The strike failed, and the steel industry saw virtually zero union organizing for more than a decade.

1922 Great Railroad Strike

Railroad maintenance and repair workers called for a strike when the Railroad Labor Board reduced their wages by 7 cents an hour—a 12% cut overall. About 400,000 railroad workers across the nation walked out on their jobs. Strikebreakers were hired to replace the original workers, and labor-related violence and picket lines ensued. U.S. Attorney General Harry Daugherty finally ended the strike by calling for a federal judge to issue an injunction against striking and organizing, technically violating First Amendment rights. However, these events led to the 1926 Railway Labor Act, which allowed railroad workers to join unions.

1934 West Coast waterfront strike

In this 82-day strike, longshoremen in every West Coast city stepped away from their jobs and demanded an independent union, lighter loads, and more men per crew loading cargo ships. After violence broke out, rifts arose between longshoremen's and seamen's unions, and the Roosevelt administration became involved in an attempt to end the strike. Longshoremen eventually gained recognition of a coastwide union, higher wages, and a union-controlled hiring hall.

1945 United Auto workers' strike

The 113-day United Automobile Workers strike against General Motors was one of a series of sizable walkouts in the years following WWII. With the end of the wartime economy, which had held down wages, the UAW, headed by Walter Reuther, stopped production, demanding a 30% pay increase and calling for GM to stop artificially raising car prices through “planned scarcity,” which led to lost jobs. In the end, the UAW and GM settled on a 17.5% pay raise, overtime pay, and paid time off.

1946 United Mine Workers of America strike

At the culmination of an eight-month-long nationwide strike organized by the United Mine Workers of America to demand health benefits and higher pay, the U.S. government proposed an agreement with the union known as The Promise of 1946. The promise dictated that miners would receive a welfare and retirement pensions, as well as a separate health fund. It was a pivotal point in the history of labor rights for miners.

1968 New York teachers' strike

When the school board in Brooklyn's neighborhood of Ocean Hill-Brownsville transferred over a dozen white Jewish teachers and administrators out of their predominantly black and Hispanic schools, the United Federation of Teachers pushed back, calling the board's action anti-Semitic. Essentially, black parents and administrators thought that black teachers ought to be teaching their children. As white teachers tried to return to work, hundreds of board-supporting community members and teachers blocked their paths, giving way to a 36-day shutdown of local public schools. In the end, the New York State Education Commissioner seized control of the Ocean Hill-Brownsville district and rehired the transferred teachers.

1970 postal workers' strike

Postal workers in New York City and other cities across the country ceased work for eight days due to low wages and substandard working conditions. A meager 5.4% pay increase compared with a 41% boost in congressional pay angered postal workers, whose 200,000-strong work stoppage led to the establishment of the Postal Reorganization Act of 1970. The act combined the major postal unions into the U.S. Postal Service and facilitated collective bargaining rights.

1983 Arizona copper mine strike

The Phelps Dodge Corporation butted heads with unions when the price of copper dropped in 1981 and the company laid off thousands of workers. Ultimately, Phelps Dodge was able to stay afloat, though it cut the cost of living adjustment from miners' contracts, established worker health care copays, and reduced wages for new employees. As the strike wore on, the National Labor Relations Board gave approval when workers voted to decertify 13 unions associated with Phelps Dodge, the largest decertification in U.S. labor history.

1995–1997 Detroit newspaper strike

Six labor unions and 2,500 people were at the center of this lengthy newspaper strike that lasted over a year after management of the Detroit Free Press and The Detroit News moved to crush unions by hiring independent contractors instead of staff writers. The Detroit papers continued publication despite the walkout, and strikers started publishing their own paper. However, many strikers eventually went back to work for the Free Press and The News, and the unions ended the strike because of high costs.

2000 Verizon strike

After Bell Atlantic and GTE merged to form Verizon, the new company decided to move stores and offices to non-union locales, forcing many employees to relocate or lose their jobs. On top of that, employees were required to work extra overtime hours. About 85,000 union members of the Communication Workers of America and the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers went on strike for 18 days. The strike ended when Verizon agreed to cap overtime at 10 hours a week and also gave a small pay increase to bilingual workers providing customer assistance in other languages.

2007–2008 Writers Guild of America strike

Film and TV writers belonging to the Writers Guild of America went on strike asking for higher compensation. The three-month walkout resulted in the laying off of hundreds of writers and production assistants, and the “Big Four” networks saw significant drops in prime-time ratings and had to scramble for content, which many think led to the rise of reality TV.

2012 Chicago teachers' strike

In the first Chicago teachers' strike since the '80s, the Chicago Teachers Union went up against the city of Chicago asking for higher pay and benefits plans, protections for teachers laid off due to school closings, a curriculum that included art, music, and gym, less high-level testing for students, and smaller class sizes, among other things.

2018 West Virginia teachers' strike

This pivotal strike involved about 20,000 teachers and staffers from 55 state counties helmed by the West Virginia branch of the American Federation of Teachers and the National Education Association. Teachers gathered in front of the West Virginia State Capital in a fight for higher pay and lower health care costs. The strike ended when the West Virginia Senate approved a 5% pay increase, though it could not offer a solution to spiking costs of health care. This action inspired teachers in Oklahoma, Colorado, Arizona, and other states to strike on similar grounds later in 2018.

2019 surge in strikes

In 2018 and 2019, 455,400 workers on average participated in major work stoppages, "the largest two-year average in 35 years," according to the Economic Policy Institute. Teachers continued their activity from 2018 into 2019, with educators in L.A., Chicago, Denver, Oakland, Sacramento, Nashville, North Carolina, and South Carolina engaged in strikes around teacher pay and state cuts to education budgets. 2019 saw a rise in teachers' unions using their power to fight for broader issues that affect their students. The Chicago teachers' strike included calls for affordable housing, immigrant safety, and more money for the city's poor and underserved neighborhoods. Both Chicago and L.A. strikes resulted in more nurses and librarians in schools. The other big strike of the year was by auto workers. General Motors workers went on strike for 29 days. With 46,000 workers missing days of work, the GM strike was the largest strike in terms of lost work days.

2020 professional sports strike

The Milwaukee Bucks never emerged from their locker room to play their game against the Orlando Magic on Aug. 26, engaging in a strike to protest the police shooting of Jacob Blake, a Black man, in nearby Kenosha, Wisconsin. In quick succession the Milwaukee Brewers announced they wouldn't play their game that night; the rest of the night's NBA games were postponed; and games in professional soccer, tennis, women's basketball, and baseball were canceled. It's a wave of professional athletic activism without precedence. The Bucks called on the Wisconsin legislature, which has been inactive for months, to call a session to address police reform.