How the American wealth gap has increased

How the American wealth gap has increased

America's wealth gap is at historic levels, nearing the inequality that marked the exuberant years of the Jazz Age, when the country's riches were concentrated in the hands of the very top echelon.

During the Roaring Twenties, the most affluent Americans held close to a quarter of total household wealth, a number that tumbled during the Great Depression along with the stock market. But the concentration of fortune among the most prosperous has been on the rise since the 1980s, with some economists worrying that a stock market bubble will again burst with severe economic consequences.

A slew of factors contribute to the country's income inequality. Among those cited, and often disputed, are tax cuts for the wealthy, assistance to the poor, a decline in the influence of unions, globalization, technological advances, and the minimum wage's shrinking value. Liberals argue that the notion that tax cuts will spur business growth has failed repeatedly. Conservatives are less likely to say that the wealth gap is unfair, though they do donate to charities and otherwise help the poor at an individual level instead of addressing the problem systematically.

Globally, America is one of the world's richest countries but also one of the most unequal. Among developed countries in 2017, it ranked 23 out of 30 in a measure focused on income, health, poverty and sustainability. Here is a look at some significant milestones in the country's march toward that inequality. Stacker searched news reports, academic studies, and international assessments to compile this list of important moments in American history.

1920s roar like the cat’s meow

Tycoons thrived in the Jazz Age, when a list of the country’s richest compiled by Forbes in 1918 included such household names as banking giant J.P. Morgan Jr., steel tycoon Charles M. Schwab, and Vincent Astor, whose family owned a large amount of New York City real estate. At the time, the top 0.1% accounted for nearly 25% of the wealth, according to research by Gabriel Zucman, an economics professor at the University of California, Berkeley. But then came the stock market crash of 1929, and the amount of wealth held by the richest Americans fell, landing at under 10% by the late 1970s. That number later reversed and is now close to 20%.

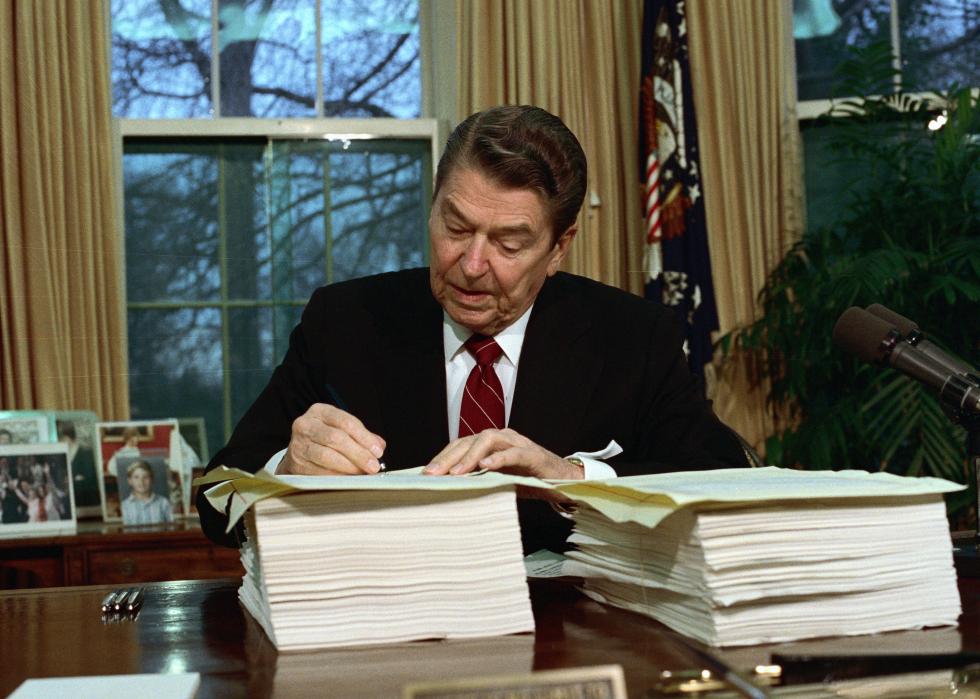

Reagan slashes tax rates

President Ronald Reagan started off decades of cuts to the tax rates paid by the country’s top earners, a trend that economists point to as one cause of the enormous wealth gap in today’s United States. The first round of Reagan tax cuts, enacted by both Republicans and Democrats, came in 1981, when the top rate dropped to 50% from 70%. The second round brought that top rate down to 28% by 1988. The country’s top 1% won a bonanza of $350,000 in tax cuts in 1985 compared to $3,500 for a typical household and a few hundred dollars for the poor, according to John Komlos, an economics historian.

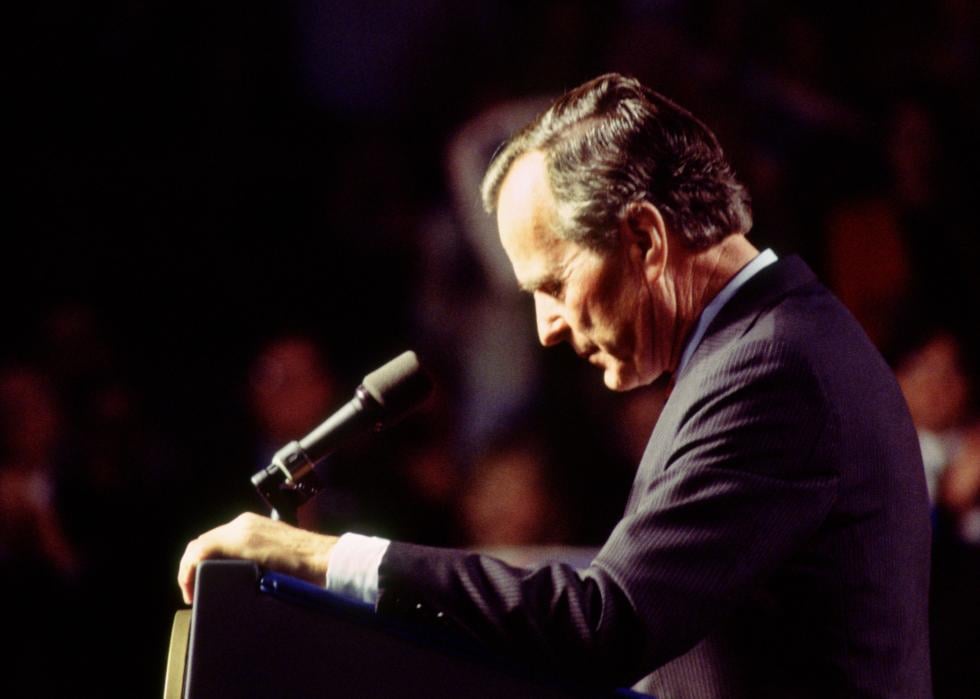

George H.W. Bush pays a political price

President George H.W. Bush, who famously campaigned on the pledge “read my lips, no new taxes,” did partly reverse President Reagan’s cuts once he was in office, and raised the top rate to 31%. He was notably skeptical of the supply-side economic theories favored by Republicans, calling them “voodoo economics” before he joined the Reagan administration as vice president. But his policies angered fellow Republicans and he paid a price. In the end, he failed to win re-election in a three-way race against Democrat Bill Clinton and independent Ross Perot and since then, no national Republican leader has favored raising taxes to keep government services.

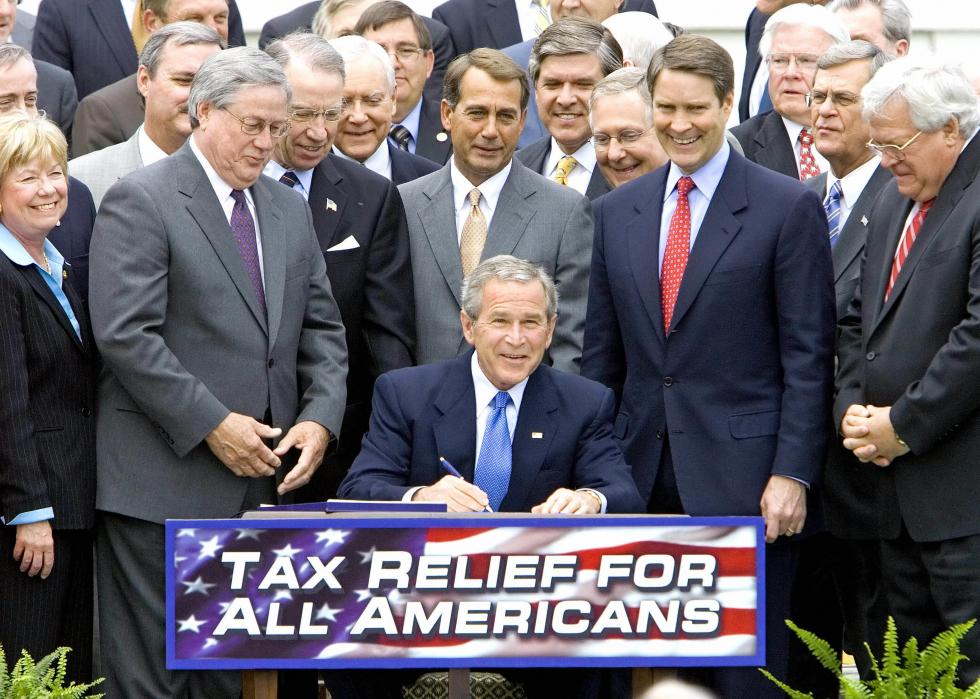

George W. Bush twice cuts taxes, benefiting the rich

The tax rate cuts under President George W. Bush mostly benefited high-income taxpayers, according to the Center of Budget and Policy Priorities. The top 1% got a tax cut of on average more than $570,000 in the years between 2004 and 2012, increasing their after-tax income by more than 5% each year as a result. Besides cutting rates, the acts also phased out the estate tax and included provisions for the middle class. The cost of the tax laws? About 2% of the GDP in 2010, the year they were fully integrated.

The Great Recession leads to widening income inequality

The burst of the housing bubble that led into the Great Recession left low- and middle-income homeowners struggling. Households in the bottom four-fifths saw a 39% drop in net worth between 2007 and 2010, while the top 20% lost only 14% of net worth. Meanwhile, the top 1 percent of household income has grown 229% since 1979, according to the Economic Policy Institute. That is far greater than for the bottom 90% of households. Their growth was just 46%.

Trump’s tax cuts exacerbate financial woes

Many economists argue that the 2017 tax cuts under President Donald Trump, promoted by the White House as a boon to the middle class, actually worsened income inequality. Three years after the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was passed—in which individual, corporate and estate tax rates were cut—wealthy Americans and large corporations stand out as the main beneficiaries. The tax cuts did not pay for themselves, as promised, and the legislation is expected to cost the country $1.9 trillion over a decade. The Brookings Institution found that the amount of tax revenue collected in the 2018 fiscal year was significantly lower than what was projected by the Congressional Budget Office—by $275 billion or 7.6% of revenues that were expected before the tax cuts took effect.

Middle class shrinks each decade, income gap grows

The share of middle-class Americans has shrunk from 61% in 1971 to 51% in 2019, and the decrease has been steady as each decade ended with a smaller percentage of adults in middle-income households than it started. Some Americans are moving into wealthier income brackets, with the share of upper-income adults growing from 14% to 20% from 1971 to 2019. Conversely, the percentage of lower-income adults increased from 25% to 29%. But middle-class incomes have not grown at the same rate as others, increasing 49% from 1970 to 2018—much less than the 64% increase for upper-income households. The Economic Policy Institute points to the labor movement’s role in building a “vibrant middle class” that has deteriorated along with lower union participation. From 1979 to 2019, de-unionization in the United States resulted in inequality growth over that 40 year period, from around 13-20% for women and 33-37% for men.

America outpaces Europe in income inequity

In 1980, the United States and Western Europe shared a similar wealth gap, with the top 1% receiving 10% of the income in both places. Since then, they have deviated significantly, according to the 2018 World Inequity Report. By 2016, Western Europe’s top 1% got about 12% percent of the income, compared to 20% in the United States. In the United States, the income share held by the bottom 50% tumbled to 13% in 2016 from more than 20% in 1980.

Black, white discrepancies worsen during the pandemic

The coronavirus pandemic worsened the gulf that already existed between Black and white wealth in the United States, as Black households had to contend with more financial emergencies with less savings. Here’s an example, offered by the liberal Center for American Progress: In 2020, nearly 47% of unemployed white households did not have $400 for an emergency, compared to 65% of unemployed Black households. One result has been a growing gap in funds for education, business start-ups, housing, and retirement between Black and white families, according to the CAP report.

Billionaires reap the riches

America's billionaires got even richer during the coronavirus pandemic, as the collapse of some parts of the economy left some workers sick with COVID-19, without jobs or health care and with their homes in jeopardy. The billionaires' wealth grew by $2.1 trillion or 70% during the pandemic, from just shy of $3 trillion in March 2020 to more than $5 trillion in October 2021; meanwhile, the bottom 50% had just $3 trillion. The number of American billionaires increased, too, from 614 in 2020 to 745 in 2021. That's according to data from Forbes, which was analyzed by two progressive groups, Americans for Tax Fairness and the Institute for Policy Studies Program on Inequality.