How the US minimum wage compares to other countries

This story originally appeared on JobTest.org and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

How the US minimum wage compares to other countries

For almost 15 years, the U.S. federal minimum wage has remained stuck at $7.25 an hour, amounting to $15,080 annually for a full-time, 40-hour week. That's just over the poverty line.

More than 3 out of 5 adults representing almost every demographic group in the U.S. favor raising the federal wage floor to $15 an hour, according to a 2021 survey by the Pew Research Center. Even among those who oppose the $15 raise, a majority still favor a slight increase.

Inflation and productivity have long outpaced the $7.25 federal minimum wage. Its purchasing power dropped 17% between 2009 and 2019, reflecting an annual loss of over $3,000 in earnings for full-time workers. It is an unlivable wage in most parts of the U.S., covering only 29% of living expenses in places like New Hampshire. The National Low Income Housing Coalition points out that the average minimum wage earner would have to work 97-hour weeks to afford rent in a two-bedroom apartment at fair market value.

What's more, swaths of low-wage workers in the U.S. aren't covered by the minimum wage umbrella. This includes tipped employees, disabled workers, and teenagers who have been employed for under 90 days.

In addition to stagnant wages and decreased purchasing power, other cutbacks are affecting minimum wage earners. Around 20% less federal spending is now going to benefits like Medicaid, public housing, and social security insurance than in the early 1990s. Squeezed between an unlivable wage and a social safety net that's wearing thin, many minimum wage earners are in an untenable situation.

The minimum wage backstory

The mandate to establish standardized pay for workers—the minimum wage—in the U.S. was almost always contentious, finally enacted by former President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1938 after years in the courts on grounds of unconstitutionality. Since its foundation, the minimum wage has been raised 22 times, creeping up from a pittance of 25 cents per hour until plateauing in July 2009.

In some cases, raising the minimum wage had an effect on equality across the economy. The 1966 raise bridged the income gap by more than 20% between Black and white Americans, according to an analysis by University of California, Berkeley researchers.

Until the 1970s, rate increases were linked to inflation and productivity—the ability to generate income by creating goods and services. By adjusting the minimum wage in tandem with other economic increases, workers were better able to keep up with rising costs.

Today, the stagnant minimum wage makes the U.S. an outlier among other countries. According to the Pew Research Center, at least 80 other countries have requirements to review their minimum wages every few years. However, unlike some other countries, the U.S. has the ability to give states, cities, and industries the power to set their own minimum wages exceeding the federal mandate. For instance, California fast-food workers earn at least $20 an hour, and in Tukwila, Washington, a $20.29-per-hour minimum wage makes it the highest local rate in the country.

Resistance to change

Some opponents of raising the rate argue that minimum wage workers are "unskilled," just getting started in the workforce, or only need extra spending money. This contradicts analysis from the Brookings Institution, a nonprofit and nonpartisan organization, which found that the majority of low-wage workers were at the peak of their earning years and were the primary breadwinners for their families.

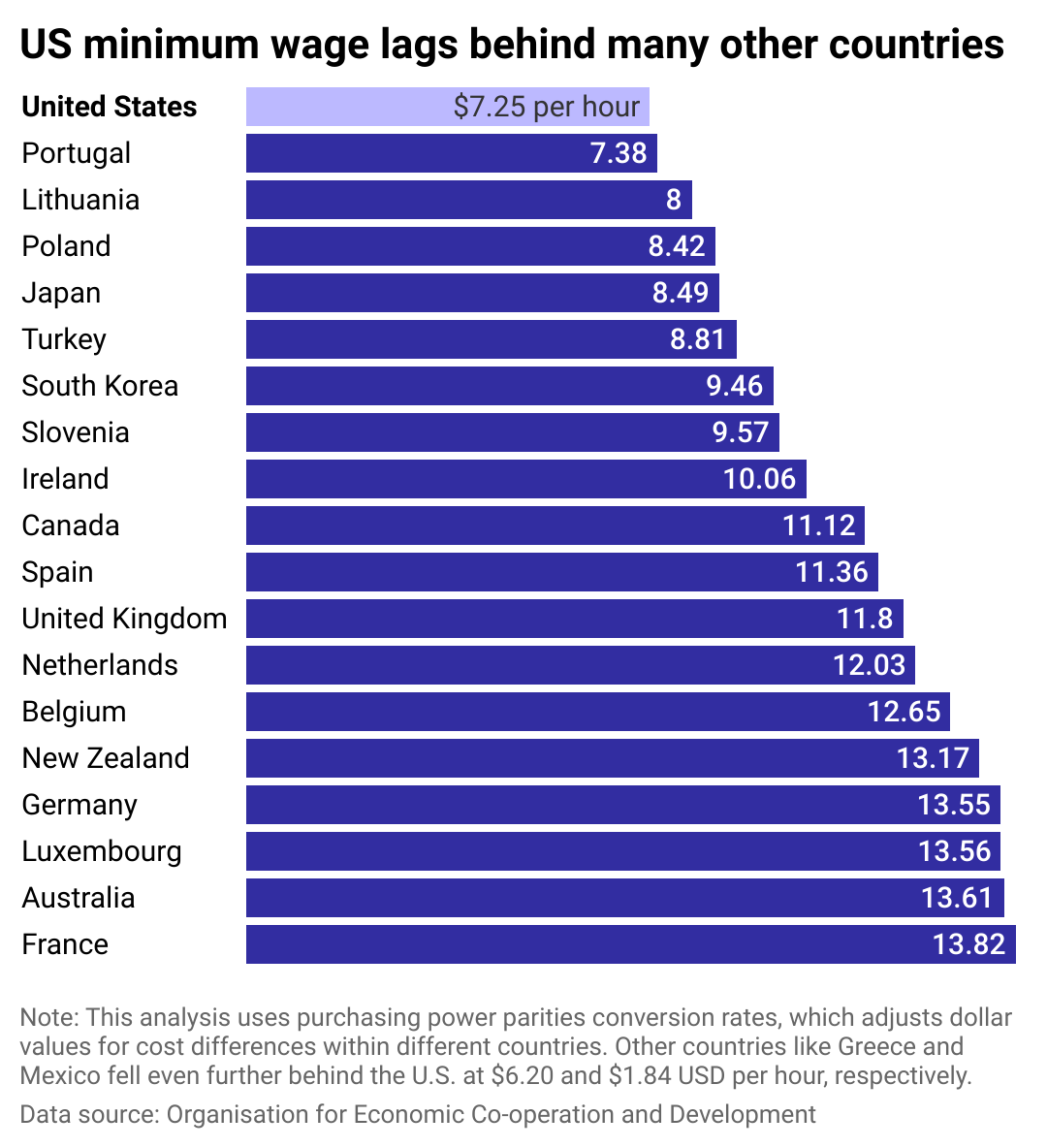

To chart the wage disparities between the U.S. and other developed nations, JobTest.org used data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development to look at minimum wages across continents. Only 18 of the 35 OECD countries are illustrated here, representing only the countries with higher minimum wages than the U.S.

This analysis used purchasing power parities conversion rates to compare earnings across currencies, adjusting dollar values for cost differences.

Across continents, minimum wages are higher than in the US

There are numerous ways that other countries around the world handle the establishment of a minimum wage. A variety of factors can impact the pay and benefits of minimum wage earners, and minimums are set by commissions, collective bargaining, or other factors.

In 2022, when inflation was around a 40-year high, minimum wage earners in the poorest countries were often hit hardest. Luckily for workers in France, Belgium, Poland, and Luxembourg, the minimum wage is essentially raised automatically, in line with price indexes. As of April 2024, only about 17% of countries have minimum wages at or above the cost of living, many of which are in Western Europe, according to data from the WageIndicator Foundation, a global nonprofit that maintains a global living wage database.

Other increases may pay lip service to economic equity but don't impact real change. For example, in Hong Kong—a region with a wage gap of 47 times between the richest and poorest residents—the government raised its minimum wage by a mere 32 cents in May 2023, pushing it up to 40 Hong Kong dollars, or around $5.10 in U.S. currency. Critics argued that the new minimum wage still falls behind what a family of two is eligible for through social services.

Other countries use government benefits to bolster—or harm—minimum wage earners. France has fought again and again since 1995 to reduce employers' contributions to social security for minimum wage workers, according to an OECD policy brief. Meanwhile, the United States, Spain, Slovenia, and Mexico make minimum wage workers pay more in social security benefits or employment taxes than workers earning the median wage.

Some states surge ahead

While the federal wage remains stuck, local jurisdictions—and even some companies—are finding a workaround. Thirty-four U.S. states and territories have surpassed the federal minimum wage to varying degrees. West Virginia bumped the wage floor slightly up to $8.75; on the higher end, beginning July 2024, Washington D.C. will pay a minimum wage of $17.50.

A number of cities, like Chicago, have introduced their own minimum wage. The rate in Illinois is $14, but in Chicago, the rate is $15.80 for companies with 21 workers or more, and it will increase again in July 2024. Some companies, including Costco and Amazon, have also instituted company-wide minimum wages.

For more than a decade, the ongoing partisan divide has thwarted attempts in Congress to override the minimum wage statute. The latest federal movement on wages was the Raise the Wage Act, a bill first introduced in 2017. Frequently resurfaced by its sponsor, Independent Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont, the latest initiative in 2023 proposed a gradual federal minimum wage increase to $17 by 2028. Currently, the bill sits in committee.

There are some bright spots on the wage horizon, however. President Biden signed an executive order in 2021 that raised the hourly wage for federal contractors to $15, with automatic increases for inflation, covering a range of workers from maintenance professionals to nurses caring for veterans.

And despite a standstill at the federal level, local jurisdictions will achieve much of what advocates have long pushed for by year's end. In 25 states as well as 60 cities and counties, the minimum wage floor has or will increase by the time 2024 comes to a close, with over half of those jurisdictions hitting a $15 minimum.

Story editing by Alizah Salario. Copy editing by Tim Bruns.