'Quick quitting': A closer look at the growing trend in the job market

This story originally appeared on Tovuti LMS and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

'Quick quitting': A closer look at the growing trend in the job market

Quiet quitting, a term coined to describe employees who simply stopped putting in extra effort at work, has gotten most of the headlines. But another phenomenon also has been underway since the coronavirus pandemic hit: quick quitting. People began to abandon the conventional wisdom that you should remain in a job—even one you dislike—for at least a year.

Those quick quitters were among a record number of workers who left their jobs in an exodus known as the Great Resignation. More than 47 million Americans quit in 2021, an increase of 33% from the year before, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. And about 50.6 million people left their jobs in 2022—double the number in 2012.

Many observers point to COVID-19 as a spur for the unprecedented departure from the workforce. However, an article in the Harvard Business Review cautioned against attributing the phenomenon to the pandemic alone, arguing the shift was part of an existing trend. Quick quitting has gone hand in hand with a tight labor market, in which workers are in demand and can leave one job confident they will find another easily.

Tovuti LMS analyzed how quick quitting has evolved, using data provided by Revelio Labs. Revelio Labs analyses draw from publicly available online job data, including LinkedIn and other sources.

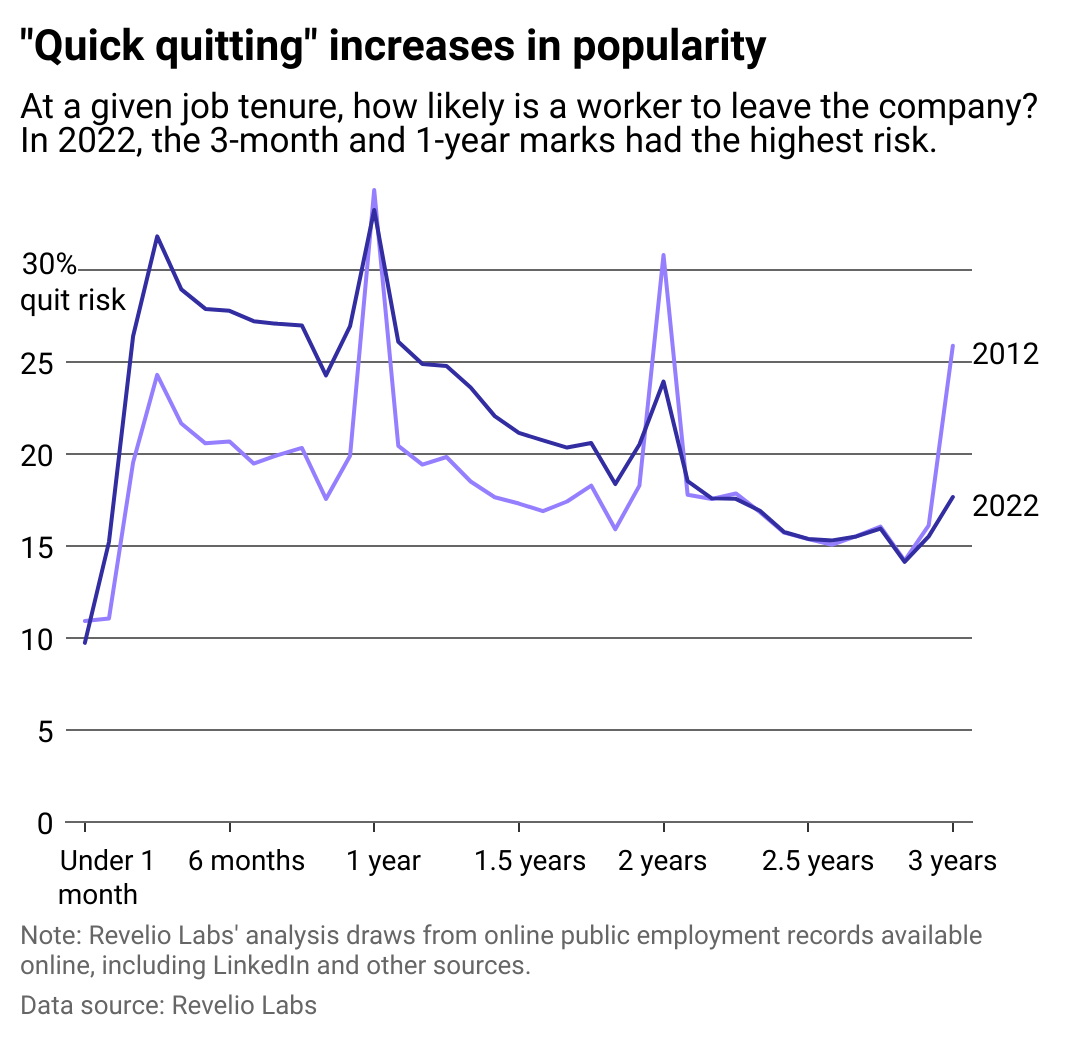

Attrition risk is highest during early employment months

The most common time for an employee to quit is three months, followed by the one-year mark. After that, the chances of a worker resigning drops significantly, with the probability that they leave within the subsequent year at only 20%, according to Revelio Labs.

Promoting hard-working employees before that one-year anniversary could encourage them to stay rather than take a better job at another company, Revelio Labs data suggests. Another possibility is to consider more options for remote work. A 2022 study by Skynova found that more than 1 in 3 workers asked to work remotely before quitting.

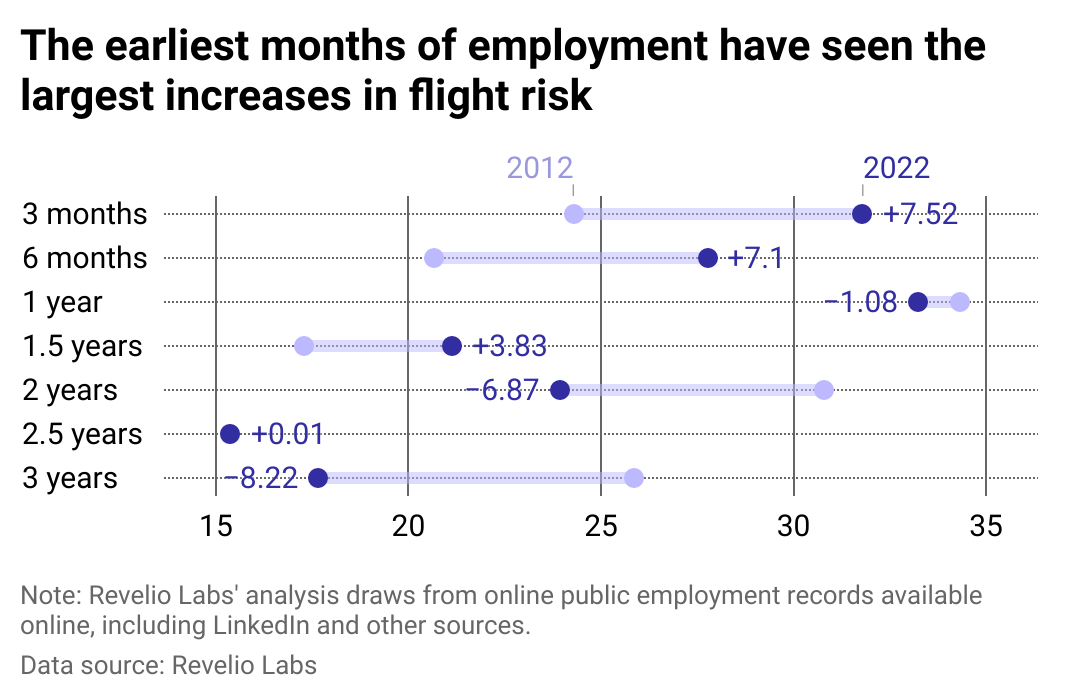

At the 3- and 6-month marks, attrition has grown significantly since 2012

When the coronavirus pandemic struck, workplaces had to become more flexible. An analysis by the investment company BlackRock published in October 2022 found that employees' expectations for their workplace had changed fundamentally.

People are prioritizing work-life balance, well-being, and career development more. They also have more opportunities for gig jobs and remote work outside a traditional schedule or office. Companies, however, have pulled back on perks and often demand employees return to the office, at least part of the time.

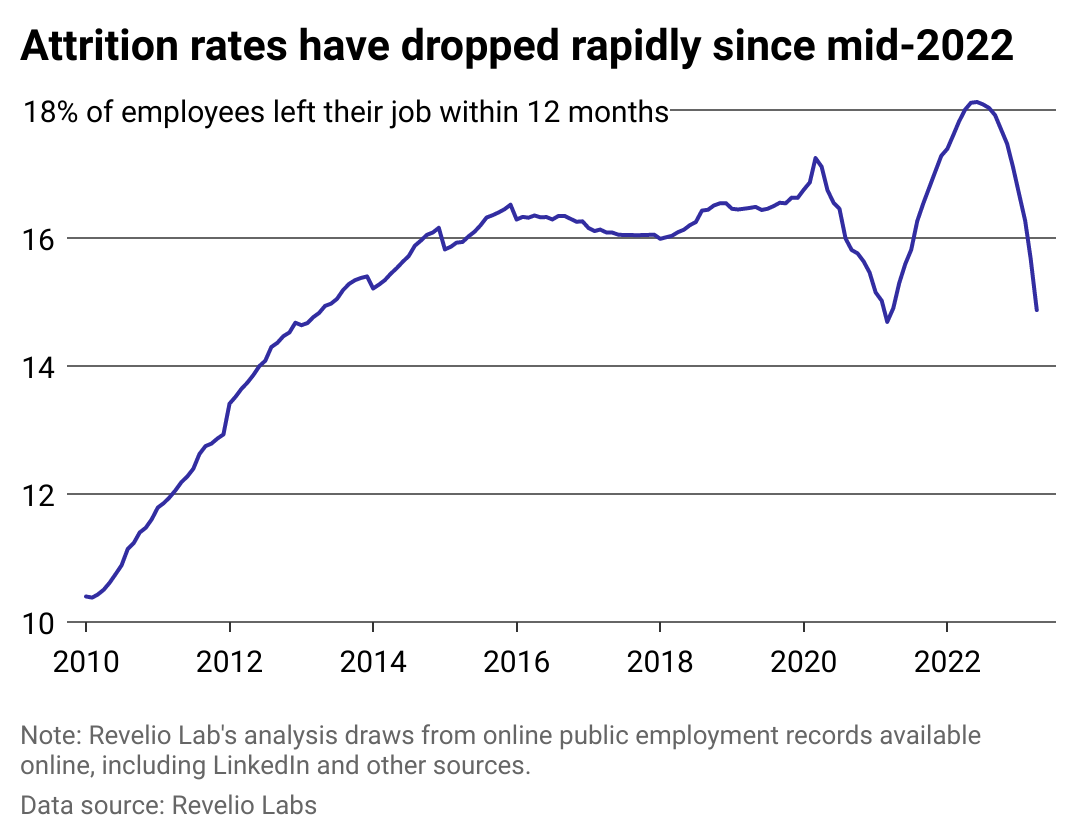

Quit rates—especially in the first year of employment—were exceptionally high in 2022

According to LinkedIn, the number of jobs held for less than a year began to grow in August 2021. By March 2022, that number was up 9.7% year-over-year. One factor driving the phenomenon has been a strong labor market, with a low unemployment rate of 3.6% in May 2022 and 3.7% a year later.

With about 10 million job openings, workers are more willing to leave a new job quickly if they are confident they can find another position. That's not to say that some industries haven't had sizable layoffs with the end of low interest rates. By the beginning of 2023, the tech industry, for example, had laid off 200,000 employees.

Many Americans feared 2023 would be the year of a recession, with high inflation and rising housing prices spurring some workers to look for a new job now, but job creation remains strong, easing some of those concerns.

Story editing by Jeff Inglis. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.