50 most common jobs held by women 100 years ago

50 most common jobs held by women 100 years ago

The past century has been a remarkable one for women in the workplace. As of August 2025, women held 49.9% of the jobs in the United States, not counting farm workers and the self-employed, according to the government's Bureau of Labor Statistics. Though women's presence in the workforce is generally unquestioned today, this represents a drastic change from just 100 years ago.

In the 1920s, 1 in 5 women were earning salaries, typically as clerks, servers, teachers, and telephone operators, laboring amid attitudes that women should not work outside the home if their husbands were employed and that working women were taking jobs away from men who needed them more. Plenty of high-paying, powerful jobs were kept out of women's reach, and women often were expected to quit their paying jobs if they got married.

Women only got the right to vote in 1920, and the Fair Labor Standards Act, signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, established a minimum wage, standardized work week, a requirement to pay overtime, and child labor bans in 1938. Not until 1963 did the Equal Pay Act formally forbid paying men and women different wages for the same work.

Of course, problems persist. Though the wage gap has narrowed, women still make about 85 cents for every dollar earned by men, and the explosive #MeToo movement illustrated how untold numbers of women have struggled with sexual harassment and assault in the workplace.

Stacker has compiled a list of the most common jobs held by women a century ago by looking at comparison tables from 1920 in the 1940 U.S. Census. The Census occupation classifications have been lightly edited, and some classifications have been removed from the dataset due to a lack of specificity.

#50. Artists, sculptors, and teachers of art

- Total female employment: 14,617

Creative occupations were open to women in the arts, and teaching was considered a natural extension of motherhood. In the 19th century, teaching had been a male profession, but industrialization brought more lucrative jobs, leaving education to women. Waves of immigration also fueled a need for teachers, especially in cities. By the 20th century, some three-quarters of teachers were women.

#49. Building, general and not specified laborers

- Total female employment: 15,235

Most women had minimal education in the early 20th century, which limited their opportunities to jobs like unskilled laborers. A 1929 report by the Women's Bureau, a government advocacy agency established in 1920, said while women's wages were critical to their family finances, the earnings of unskilled laborers were less than what was needed for a "a decent standard of living."

#48. Restaurant, cafe and lunchroom keepers

- Total female employment: 15,644

Women were educated in home economics, learning nutrition, cooking, and food management, and got food service jobs in factories, institutions, and schools. Statistics from early in the 20th century show there was one female restaurant keeper for every five male keepers. Women also dominated such jobs in cafeterias and tea rooms, both considered eating places suited for women.

#47. Cotton mill laborers

- Total female employment: 16,669

In cotton mills, women mostly worked in the spinning room, where they tended to the machines that spun the cotton into weavable thread, while men did the heavier lifting, fed the fiber into carding machines, or worked as weavers. Mill workers put in 10- to 12-hour shifts six days a week, laboring in loud, hot conditions in air filled with lint and dust. Women often brought babies and children to their mill jobs, where they would help or start learning skills for their own future employment.

#46. Glove factory operatives

- Total female employment: 16,773

As of 1920, women comprised about a fifth of the U.S. labor force, and many worked in apparel manufacturing. Gloves were still a popular fashion accessory, although on the decline as standards of modesty loosened, and tanned rather than pale skin became popular.

#45. Telegraph/radio operators

- Total female employment: 16,860

The expansion of the nation's telegraph system helped modernize business and finance when stock and commodities prices could be transmitted rapidly across the country. These early telecommunications created a demand for skilled operators, and women were hired in part because smaller hands were deemed to be suitable for the quick, detailed work and because they could be paid less than men.

#44. Rubber factory operatives

- Total female employment: 18,834

The rubber industry, and jobs in it, expanded rapidly with the demand for automobile tires, but took a hit from overproduction and tightening credit ahead of the Great Depression. Typically in factories in 1920, men would be paid 40 cents an hour, and women were paid 25 cents an hour.

#43. Charwomen and cleaners

- Total female employment: 24,955

In the 1920s, charwomen cleaned office buildings, scrubbing staircases and scouring floors. A Massachusetts state survey in 1919 of some 200 buildings found nearly all the charwomen were being paid less than $9 a week, well below the $11.65 that was considered minimal pay. The state legislature mandated a nine-hour workday for women, on grounds that they were frail and in need of protection, and many buildings responded by firing the charwomen and replacing them with men who were not covered by such restrictions.

#42. Religious and social workers

- Total female employment: 26,927

Social work jobs took off in the early 1900s with a rise in public awareness and efforts on behalf of people in need. Jane Addams, a pioneer in social work, was one of the first women to be awarded a Nobel Peace Prize. Addams built settlement houses for immigrants in Chicago. Social worker Frances Perkins was appointed secretary of labor in 1933 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, becoming the first woman to serve in the U.S. cabinet.

#41. Electrical machinery and supply factory operatives

- Total female employment: 27,389

In 1920, nearly a quarter of employed women were working in manufacturing. The U.S. Congress established the Women's Bureau, a federal agency, to oversee the working conditions of women in industry and advocate for the welfare of working women.

#40. Janitors and sextons

- Total female employment: 29,038

Janitors and janitresses were responsible for overseeing maintenance of apartment buildings, typically as live-in labor. They shoveled coal into boilers, cleaned out ash and trash, fixed pipes, did repairs, and washed windows, always on call to meet tenants' needs. Their living quarters were often in the basement.

#39. Foreman and overseers (manufacturing)

- Total female employment: 30,171

In the years following World War I, most manufacturing employees worked at plants with at least 100 workers, and a third worked at plants with more than 1,000 workers. The role of the foreman was to represent management, setting the pace of production, deciding on pay, and assigning tasks and shifts. The job also included the authority to fire workers at will.

#38. Candy factory operatives

- Total female employment: 31,368

A century ago, commercial candy production flourished. Fannie May opened its first retail candy store in Chicago, and Jujyfruits, Mound Bars, Chuckles, Gummi Bears, the Charleston Chew, Baby Ruth bars, Milky Way bars, Mr. Goodbar, Milk Duds, Heath Bars, and Reese's Peanut Butter Cups—all still popular today—made their debuts in the 1920s.

#37. Tailoresses

- Total female employment: 31,828

Tailoresses, or dressmakers, could capitalize on their sewing skills, which were traditionally taught to girls. They often would work for upper class women who did not want to sew or mend their own clothes.

#36. Printing, publishing, and engraving operatives

- Total female employment: 32,545

Printing and publishing jobs were available as the industry advanced technologically. Offset presses became the most common form of lithography, and addressing, duplicating, and labeling machines were introduced as were the first paperback books in the 1930s.

#35. Barbers, hairdressers, and manicurists

- Total female employment: 33,246

Opportunities for hairdressers and manicurists grew as the salon business grew, and women no longer were having their hair styled by servants. In the 1920s, nearly 25,000 hair salons opened in the United States, and women enjoyed such innovations as electric hair dryers, permanent waves, and hair color.

#34. Iron and steel and machinery factory operatives

- Total female employment: 36,338

To equip an industrializing nation, manufacturers were busily producing the equipment the country's consumers needed. The machine tool industry was booming to meet demand for sewing machines, typewriters, railroad supplies, armaments, automobiles, and airplanes.

#33. Non-specified textile mill operatives

- Total female employment: 36,374

Women found work in textile mills in part because their low wages kept production costs down. At best, no matter what their skill level, they were paid three-quarters of what unskilled men earned. Women working in textile mills suffered from high rates of brown lung disease, and there was little protection against machinery accidents.

#32. Shirt, collar, and cuff factory operatives

- Total female employment: 42,016

In women's fashion, the functional, button-down blouse called a shirtwaist became the popular staple for working women, so its production was a source of employment. Shirtwaists were embellished with lace or detailed stitching on the collars and cuffs. A working woman in a crisp, tailored shirtwaist became a lasting image of the women's rights movement of the era.

#31. Other manufacturing industry operatives

- Total female employment: 46,196

Women were finding more jobs in an array of industries such as chemical, glass, and metal manufacturing as the nation industrialized, and they were doing less in traditional piecework at home. Due in part to pressure by the federal Women's Bureau and trade unions, by the 1920s, 45 states instituted 10-hour days and 50-hour work weeks. The other five states had 54-hour work weeks.

#30. Woolen and worsted mill operatives

- Total female employment: 61,715

Women found work in mills when male workers were called away to fight in World War I. Children often would accompany their mothers until child labor laws brought an end to the practice. Jobs in woolen mills declined with competition from overseas manufacturing.

#29. Suit, coat, and overall factory operatives

- Total female employment: 64,515

The garment industry grew with consumer demand for cheaper clothes, spurred by increased mail-order catalog and department store sales. To find cheap labor and lower production costs in the early 20th century, many manufacturers moved out of New York City for smaller urban areas like Cincinnati and Baltimore where they could build large, more efficient factories and pay lower wages.

#28. Milliners and millinery dealers

- Total female employment: 69,598

Jobs in millinery were on the decline in the early 1900s, amid growing demand for ready-to-wear accessories. Hat styles for women after World War I were smaller and less showy, and the popularity of hats declined in the decades that followed.

#27. Musicians and teachers of music

- Total female employment: 72,678

Women came to dominate teaching jobs in the early 20th century, when education was seen as acceptably akin to motherhood. As such, the jobs were low-paid and subject to close supervision by administrators. Music education was typically taught by elementary school teachers, most of whom were women.

#26. Silk mill operatives

- Total female employment: 72,768

Silk mills were lucrative, but labor-intensive endeavors in the early 1900s. The silkworms had to be well-protected, and the silk itself cleaned, separated into skeins, wound onto bobbins, twisted into yarn, and put on looms for weaving. After the Great Depression, the tedious jobs were less desirable, and competition from synthetics fibers like rayon took a toll as well.

#25. Shoe factory operatives

- Total female employment: 73,412

Shoemaking factories were tedious and dangerous workplaces, with a constant threat of machinery fires, but the mechanization of production provided plentiful jobs. Men operated heavy machinery, and women did lighter work such as cutting, pasting, finishing, stitching, and packing.

#24. Retail dealers

- Total female employment: 78,980

Jobs for women in retail were in supply as the growth of the cosmetics and beauty market required women to sell products to other women. Small shops that sold dresses and accessories also provided work. The jobs were considered respectable, and the hours decent compared with factory and farming work.

#23. Knitting mill operatives

- Total female employment: 80,682

The highest-paid and most skilled workers in knitting mills were men who were trained to operate the machinery and handle the dye processes. Women tended to do skilled or semi-skilled work such as transferring the tops of stockings onto circular knitting machines run by other women who would attach the feet of the stockings. Other jobs done by women were sorting, inspecting, folding, and mending.

#22. Laundry operatives

- Total female employment: 80,747

Demand for commercially done laundry rose as urban areas grew more industrialized, polluted, and dirty. Laundries became mechanized, but many did washing by hand, and women took in washing or worked in middle- and upper-class homes. While the laundry business declined overall during the Great Depression, people still sought out linen services and laundries for washing, starching, and pressing men's shirts.

#21. Cigar and tobacco factory operatives

- Total female employment: 83,960

Employees in cigar and tobacco factories typically worked on assembly lines, divided by gender and by race, doing tedious, repetitious labor. Women would inspect tobacco leaves, roll cigars, pack boxes, or apply labels, while men did more physically strenuous tasks.

#20. Boarding and lodging housekeepers

- Total female employment: 114,740

Demand for boarding and lodging grew as workers, especially women, would move away from home to find jobs. In 1923, 1 in 5 employed young women lived away from their family home. Some estimates say as many as a half to a third of American families in cities took in boarders and lodgers in the early 20th century.

#19. Waitresses

- Total female employment: 116,921

In the 1920s, low- and moderate-priced restaurants like cafeterias and luncheonettes grew popular, and it became more common for families to go out for meals, especially on Sundays. In these less formal eateries, women instead of men were hired as servers and became the majority of food-service staff. Prohibition from 1920 to 1933 negated concerns over women serving alcohol, and waitresses were considered friendlier and more attractive to customers.

#18. Other clothing factories operatives

- Total female employment: 124,350

Women working in clothing factories held most of the jobs on the shop floor, but rarely moved to higher paying positions. Public awareness and concern over their working conditions improved in the wake of the Triangle Shirtwaist fire in 1911 in New York City that came to symbolize abusive working conditions. The fire broke on the eighth floor of the Triangle garment factory, and 146 workers died, most of them young female immigrants, trapped by locked doors and a lack of fire exits.

#17. Midwives and nurses (not trained)

- Total female employment: 137,431

Jobs as midwives were waning as the medical profession adopted the attitude that births required trained professional doctors in hospital settings. But while a growing number of middle-class women began choosing doctors over midwives and home births, midwifery did expand in isolated regions and among poor and immigrant communities.

#16. Trained nurses

- Total female employment: 143,664

At the turn of the century, most nurses went into private duty, working for individual patients in their homes, but that changed with World War I, when 23,000 American nurses served in the military. When they returned home, they could use their training at hospitals that were providing increasingly sophisticated care.

#15. Cotton mills operatives

- Total female employment: 149,185

Women living in the South could find work in textile mills. Women tended to hold mill jobs that involved guiding the fibers into machines that cleaned and smoothed the cotton before spinning. Women were often preferred as employees because they could be paid less than men. Mills in the South did not hire Black women, however, due to segregation policies.

#14. In-store clerks

- Total female employment: 170,397

The growth of large-scale retailing at the start of the 20th century provided unprecedented job opportunities to women as in-store clerks. Before the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, they worked long hours, standing all day on their feet in poor conditions for low pay. Yet sales clerk jobs were considered respectable and sought after, compared with options such as domestic or factory work.

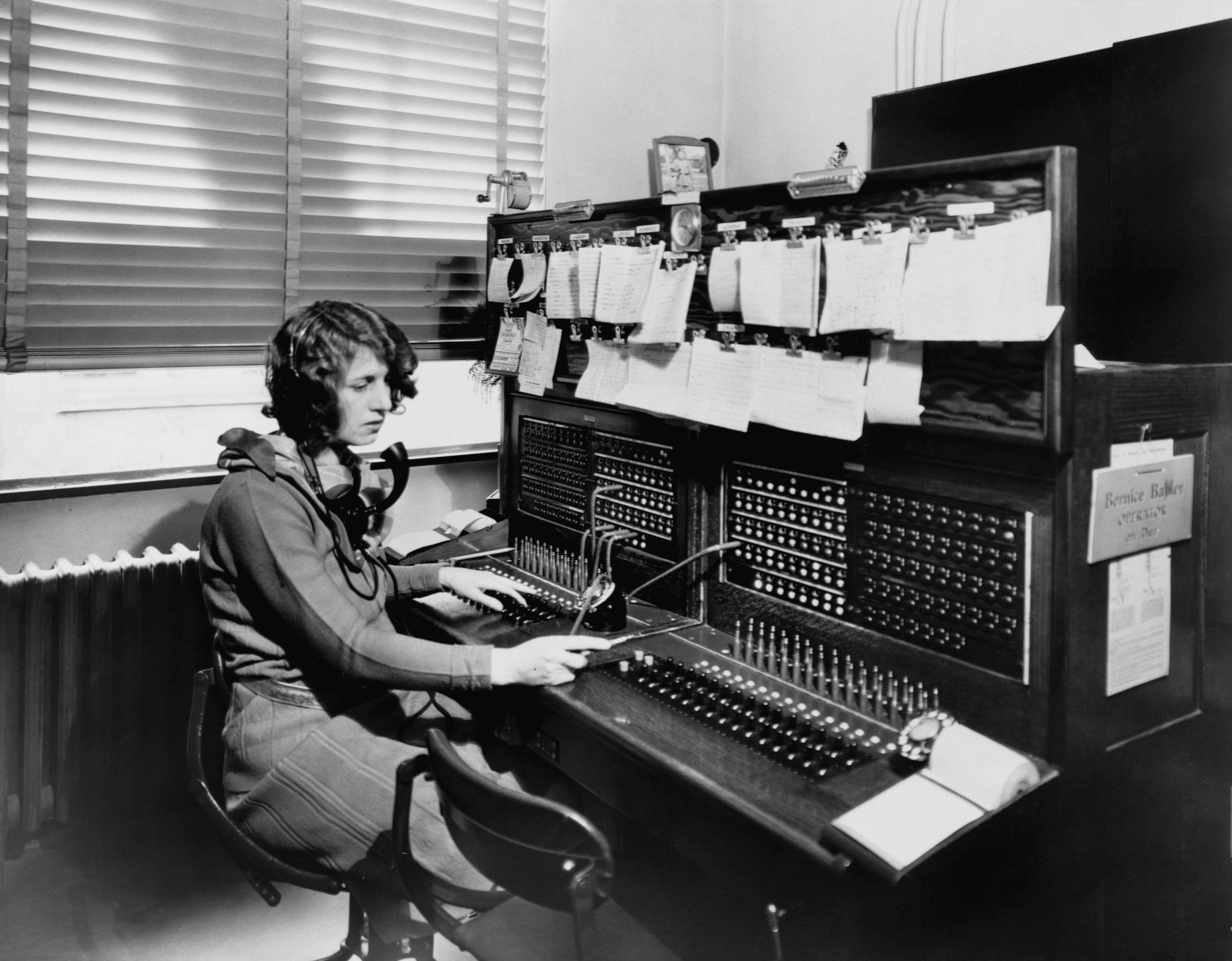

#13. Telephone operators

- Total female employment: 178,379

Originally, operators at early telephone companies who manually connected calls on a switchboard were teenage boys. But they proved to be unruly employees, and the idea of hiring women for their more soothing voices was introduced. These "hello girls" often took diction and elocution classes to improve their voices, and immigrants with discernible accents weren't hired. This avenue of employment for women grew as more homes acquired telephones.

#12. Housekeepers and stewards

- Total female employment: 204,530

More women worked in domestic service than in any other occupation according to every 10-year census from 1870 to 1940. Housekeepers were the heads of female staff, managing employees that might include cooks, nannies, housemaids, kitchen maids, laundry maids, and scullery maids.

#11. Dressmakers and seamstresses (not in factory)

- Total female employment: 235,519

Seamstress and dressmaking jobs were open to women, although they were low-paying, seasonal, and demanding, but they were under pressure in the early 1900s with the expansion of department stores and ready-to-wear fashion. Mary Brooks Picken, who would write nearly 100 books on sewing and dressmaking, opened the Women's Domestic Institute correspondence school in Scranton, Pennsylvania, that taught women to sew and set up businesses as seamstresses.

#10. Farmers

- Total female employment: 265,577

Farming was a family business, and women did every job from menial tasks to the finances, and they often supplemented the family income by selling eggs and produce for cash. They also handled seasonal jobs like slaughtering, canning, and pickling. The 1920s were a time of agricultural depression, and farmers faced falling prices, a need to buy costly machinery for large-scale harvests, debt, and the threat of foreclosure.

#9. Cooks

- Total female employment: 268,618

Not only was cooking a traditional role for women, but they started learning domestic science, or home economics, at schools that included culinary training. In the early 20th century, domestic science education at colleges and universities trained women in nutrition, quantity cooking, and large-scale dining management, and those degrees helped them find work in the restaurant and hospitality industries.

#8. Saleswomen (stores)

- Total female employment: 356,321

The rise of department stores, which offered customers a wide selection of goods and the chance to aspire and browse, provided jobs for urban working-class women. Saleswomen were paid half as much as men, considered a stable workforce because they had fewer other job options, and were familiar with household products for sale. But while the jobs entailed shorter hours than factory work, saleswomen faced huge fines for job infractions like sitting down as well as uncompensated overtime and sexual harassment.

#7. Bookkeepers, cashiers, and accountants

- Total female employment: 359,124

Economic growth created demand for clerical workers such as bookkeepers, cashiers, and accountains. Such jobs were seen as an improvement over factory work, and by the 1920s, public schools were teaching classes for girls in office skills. The jobs tended to be filled by young women who were expected to leave when they got married.

#6. Launderers and laundresses (not in laundry)

- Total female employment: 385,874

Launderers and laundresses took in other people's washing or worked in other people's homes. The job would involve sorting, washing, starching, ironing, and folding. As of 1920, about a quarter of laundry workers in Chicago were Black, working jobs that provided a step out of agricultural work. The jobs fell into decline with the Great Depression, when people could no longer hire outside help, and with the growing use of electric washing machines.

#5. Non-store clerks

- Total female employment: 472,163

These days, a non-store clerk would likely work in an enterprise that is not brick and mortar, like Amazon or other e-business. A hundred years ago, it might have meant clerks working in back offices. By the 1920s, such jobs were so acceptable and plentiful for women that clerical skills were taught in Chicago's public schools.

#4. Stenographers and typists

- Total female employment: 564,744

Stenographers used shorthand to take down dictation, and typists wrote it up, typically in groups or pools, and speed was critical. The jobs were considered stepping stones to becoming office secretaries.

#3. Teachers

- Total female employment: 639,241

Teaching was considered an acceptable job for women, but the wages were terrible and conditions difficult. Teachers could lose their jobs for their teaching methods, criticizing an administrator, wearing the wrong clothing or hairstyle, being over 40, or getting married.

#2. Servants

- Total female employment: 743,515

Fitting traditional roles, women had options to be domestic servants, such as housekeepers, housemaids who had lower status, governesses, nannies, and nursery maids. As fans of television's period piece "Downton Abbey" know, lady's maids helped the women of the house with dressing, fixing their hair, applying their makeup, and running their baths.

#1. Farm laborers

- Total female employment: 890,230

Nearly a third of all Americans worked on farms a century ago, when the farm population numbered almost 32 million, according to U.S. Census data. Everyone in the family had responsibilities, including women and children, who gathered eggs, tended to gardens, preserved vegetables, and milked cows.