How the pandemic impacted teacher shortages—and ways schools are adapting

This story originally appeared on HeyTutor and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

How the pandemic impacted teacher shortages—and ways schools are adapting

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic swept the country and closed schools, teacher shortages were a problem. In 2016, Learning Policy Institute, a nonprofit research group, estimated that American schools were short more than 100,000 teachers. The group's "A Coming Crisis in Teaching?" report found that between 2009 and 2014, enrollment in teaching education programs had dropped 35%, which resulted in approximately 240,000 fewer new teachers entering the workforce.

HeyTutor cited data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics to examine the impact of the pandemic on teacher shortages and to explore new policies and initiatives school districts have implemented to counter this issue.

The pandemic worsened the problem as more teachers left the profession, worn out by low wages, the unique difficulties of remote learning, and political fights over what they can teach in schools. They worried about their health and the health of others in their families. School shootings added further tension.

Approximately 300,000 public school teachers and other staff quit the field between February 2020 and May 2022, according to the Wall Street Journal, citing data from the BLS: That's a decrease of almost 3%. At the start of this school year, 44% of public schools had vacancies for full- or part-time teaching positions, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. In more than 60% of schools with at least one vacancy, the openings resulted from resignations related to COVID-19.

Federal assistance came in multiple forms: The Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief fund was distributed in three waves—most recently as a portion of the American Rescue Plan. The Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds pumped billions into the public school system to ease teacher shortages, bolster in-classroom safety protocols, and provide technical support to students transitioning to remote learning.

Still, shortages remain, and the national public school system is attempting to address the shortage of new teachers entering the classroom while reinvigorating its employees—teachers and support staff alike.

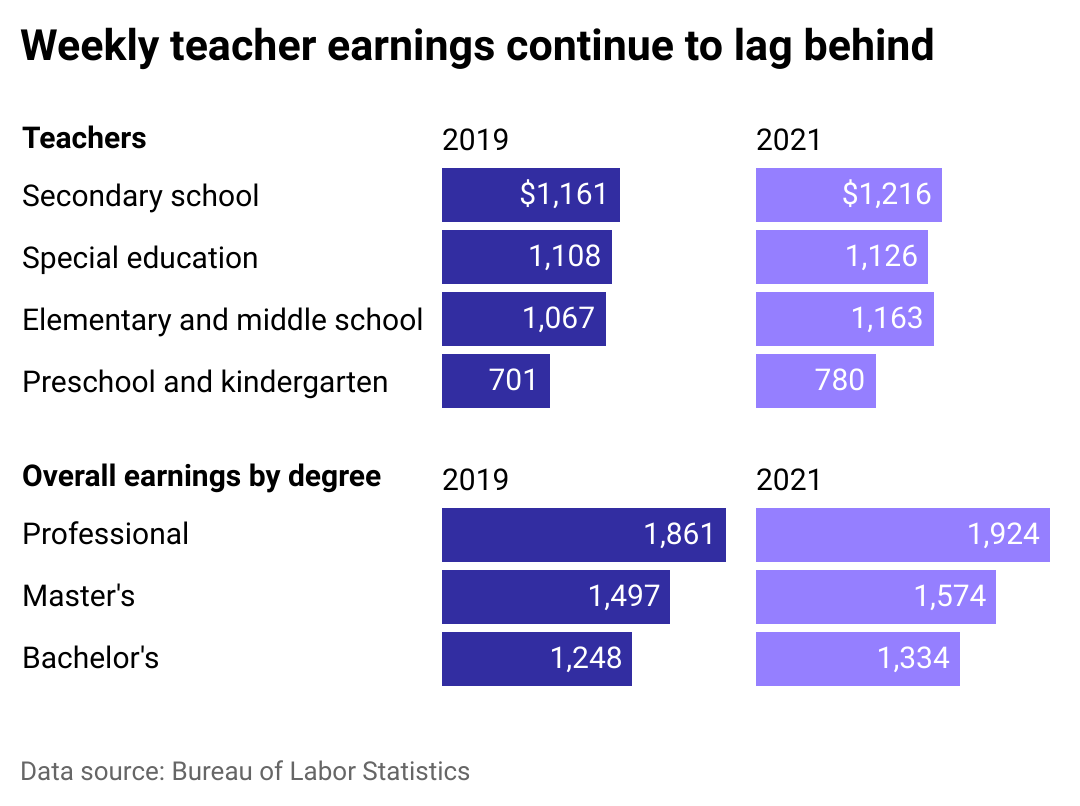

With teachers making less than other college-educated professionals, there are more calls for salary increases

The average national salary has increased over the past decade by just 0.9% when adjusted for inflation, according to the National Education Association, the country's largest teachers union. The highest average teacher salaries in the 2019-2020 school year were found in New York at $87,069, California at $84,531, and Massachusetts at $84,290. The lowest were in Florida ($49,102), Mississippi ($46,843), and South Dakota ($48,984).

However, a growing number of states are giving teachers pay raises to tackle shortages in the classroom. The salary hikes are some of the largest in decades, particularly in states where teacher earnings have traditionally been much lower than elsewhere in the nation.

New Mexico, for example, increased base salary levels by 20% on average in March 2022. Florida is raising teachers' starting salary to $47,000 from an infusion of $800 million approved in the state's most recent legislative session. Mississippi approved a salary increase that will boost teachers' pay by 10%, an average of $5,100. Alabama will offer pay increases from 4% to almost 21%, while Georgia planned $2,000 bonuses for its teachers.

Mental health support and well-being programs for teachers aim to decrease staff turnover

A Rand Corporation survey conducted early in 2021 found that 1 in 4 teachers strongly considered leaving their positions before the end of the 2020-2021 school year, and since that report, it seems stress levels for teachers have not dissipated. Rand conducted a further survey in January 2022, published in June, which found levels of stress in teachers and school principals to be twice that of the general working public. But only one-third of school leaders had made counselors or mental health services available to staff since the beginning of the pandemic, according to a 2022 Education Week survey.

K-12 teachers are the most likely to report feeling anxious, stressed and burnt out. A January 2022 report issued by the NEA found that 55% of surveyed educators planned to leave the profession early, either through taking early retirement or resigning their positions. Mental health resources for teachers, while not stemming from a single nationalized source, do exist. Teach for America has created a repository list of resources, and the NEA also offers assistance.

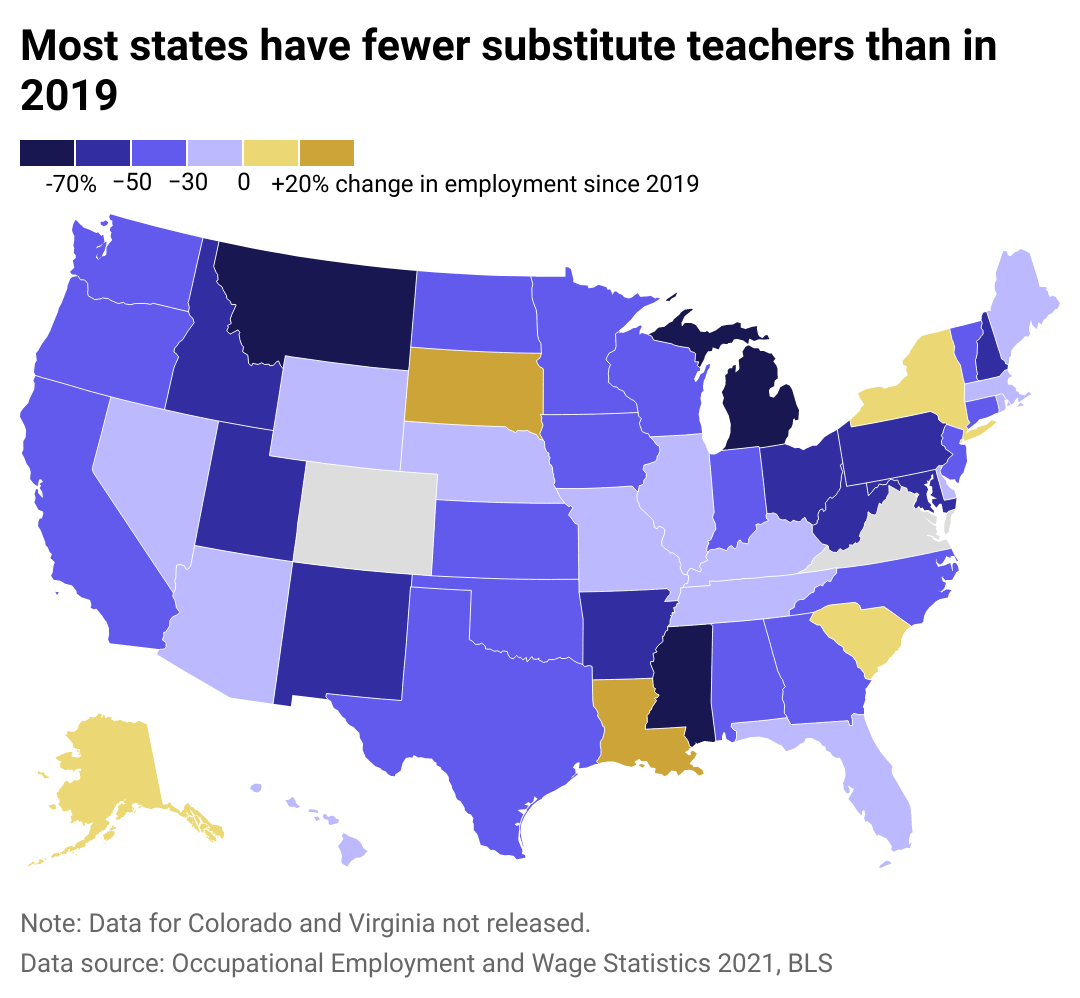

Increased attention on substitute teacher staffing

The coronavirus pandemic made the problem of teacher shortages more visible as schools scrambled to find substitutes for ill or quarantining staff. Qualified substitutes also have been in short supply, with the Brookings Institution citing Ohio's Madison school district as having fewer than one-third of the number of substitutes needed to cover its classrooms.

States have loosened some regulations to draw in teachers. Nevada, Iowa, and Missouri no longer require substitute teachers to have earned a minimum of 60 hours of college credits or an associate's degree, while Connecticut has eased the requirement that substitutes hold a bachelor's degree. Substitutes in New York can enter the classroom without a teaching degree. New Mexico turned to the state's National Guard to help plug the substitute gap.

The problem is not evenly spread among schools, however. A Brookings Institution study found that nearly half of teachers in schools with the highest number of Black and Hispanic students reported difficulty finding substitutes, compared to only 9% of teachers in schools with the lowest number of Black and Hispanic students.

More attention on high teacher turnover and its impact on students

The pandemic further exacerbated another ongoing problem: the trouble some school districts have retaining teachers.

Even before the pandemic, some high-needs schools reported turnover of as much as 30%. Among the reasons cited by teachers for choosing to leave the profession were low salaries that failed to keep up with inflation and significant increases in stress leading to general mental health concerns.

The resulting strain on those teachers and support staff who choose to remain means an increased workload, potential disruptions to student scheduling and curriculum, and increased costs to the school district. Hiring new teachers can cost a school system from $15,000 to $30,000 for recruitment and training.

Less experienced teachers can result in lower test scores and poor performances by students—this continues to be of particular concern in light of the release of the National Assessment of Education Progress report. The study found what Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona calls an "appalling and unacceptable" drop in overall test scores nationwide resulting from the mass disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Some schools have switched to four-day weeks

Four-day school weeks had already gained popularity before the coronavirus pandemic hit. A Brookings Institution study found that 662 school districts in 24 states had turned to them before the pandemic forced schools to close, an increase of 600% since 1999.

By 2022, more than 800 districts have gone to four-day weeks, with the trend noticeable in rural areas of the Midwest and the South—dozens of districts in Texas, Missouri, Colorado, and Oklahoma had adopted them. The Brookings study reported that many teachers prefer the four-day week, but the authors still offered several cautions for districts to consider. Although the shortened week provided the districts more flexibility, they did not appear to save money overall. Some research found that student achievement fell, so school districts were urged to keep instructional time the same.