When schools experimented with $10,000 pay hikes for teachers in hard-to-staff areas, the results were surprising

This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education, and reviewed and distributed by Stacker Media.

When schools experimented with $10,000 pay hikes for teachers in hard-to-staff areas, the results were surprising

School leaders nationwide often complain about how hard it is to hire teachers and how teaching job vacancies have mushroomed. Fixing the problem is not easy because those shortages aren't universal. Wealthy suburbs can have a surplus of qualified applicants for elementary schools at the same time that a remote, rural school cannot find anyone to teach high school physics.

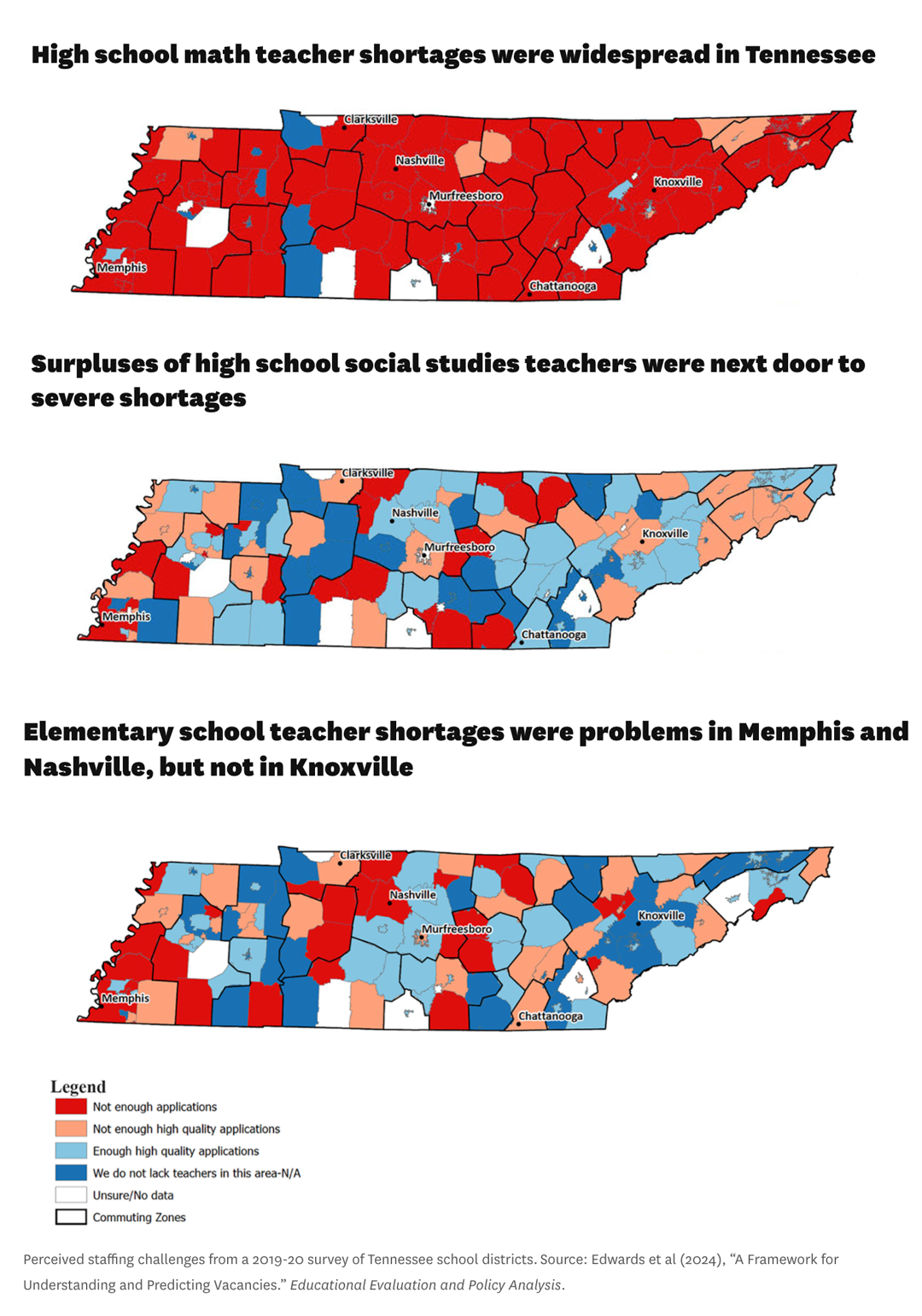

The Hechinger Report analyzes findings from a study published online in April 2024 in the journal Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis that illustrates the inconsistencies of teacher shortages in Tennessee, where one district had a surplus of high school social studies teachers, while a neighboring district had severe shortages. Nearly every district struggled to find high school math teachers.

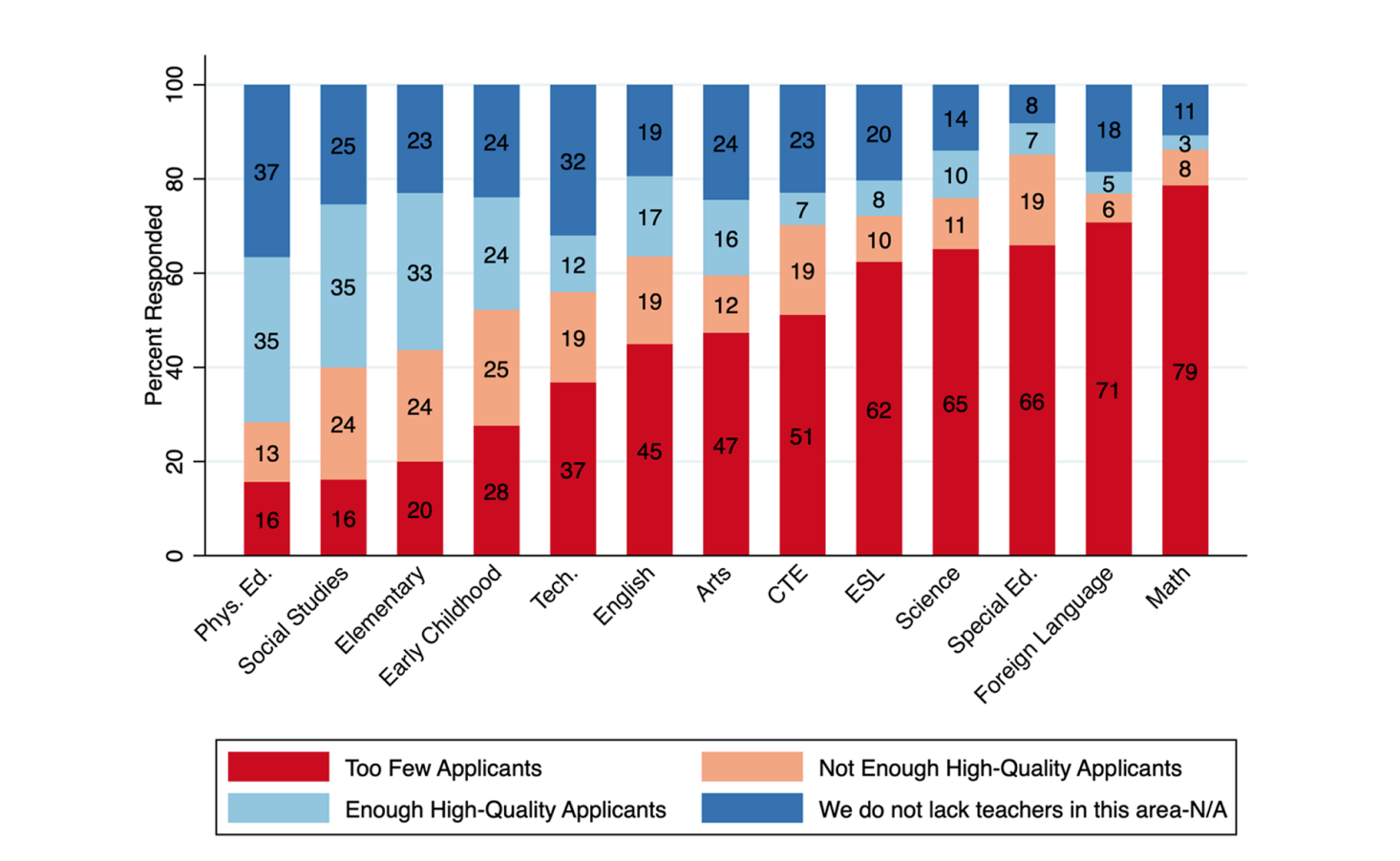

Tennessee's teacher shortages are worse in math, foreign languages and special education

(above, A 2019–2020 survey of Tennessee school districts showed staffing challenges for each subject. Tech = technology; CTE = career and technical education; ESL = English as a second language. Source: Edwards et al (2024), "Teacher Shortages: A Framework for Understanding and Predicting Vacancies." Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis.)

Economists have long argued that solutions should be targeted at specific shortages. Pay raises for all teachers, or subsidies to train future teachers, may be good ideas. But broad policies to promote the whole teaching profession may not alleviate shortages if teachers continue to gravitate toward popular specialties and geographic areas.

Targeted financial incentives can have unintended consequences

Some school systems have been experimenting with targeted financial incentives. Separate groups of researchers studied what happened in two places – Hawaii and Dallas, Texas, – when teachers were offered significant pay hikes, ranging from $6,000 to $18,000 a year, to take hard-to-fill jobs. In Hawaii, special education vacancies continued to grow, while the financial incentives to work with children with disabilities unintentionally aggravated shortages in general education classrooms. In Dallas, the incentives lured excellent teachers to high-poverty schools. Student performance subsequently skyrocketed so much that the schools no longer qualified for the bump in teacher pay. Teachers left and student test scores fell back down again.

This doesn't mean that targeted financial incentives are a bad or a failed idea. But the two studies show how the details of these pay hikes matter because there can be unintended consequences or obstacles. Some teaching specialities – such as special education – may have challenges that teacher pay hikes alone cannot solve. But these studies could help point policy makers toward better solutions.

Roddy Theobald, a statistician at the American Institutes for Research (AIR), presented a working paper, "The Impact of a $10,000 Bonus on Special Education Teacher Shortages in Hawai'i," at the annual conference of the Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research. (The paper has not yet been peer-reviewed or published in an academic journal and could still be revised.)

In the fall of 2020, Hawaii began offering all of its special education teachers an extra $10,000 a year. If teachers took a job in a historically hard-to-staff school, they also received a bonus of up to $8,000, for a potential total pay raise of $18,000. Either way, it was a huge bump atop a $50,000 base salary.

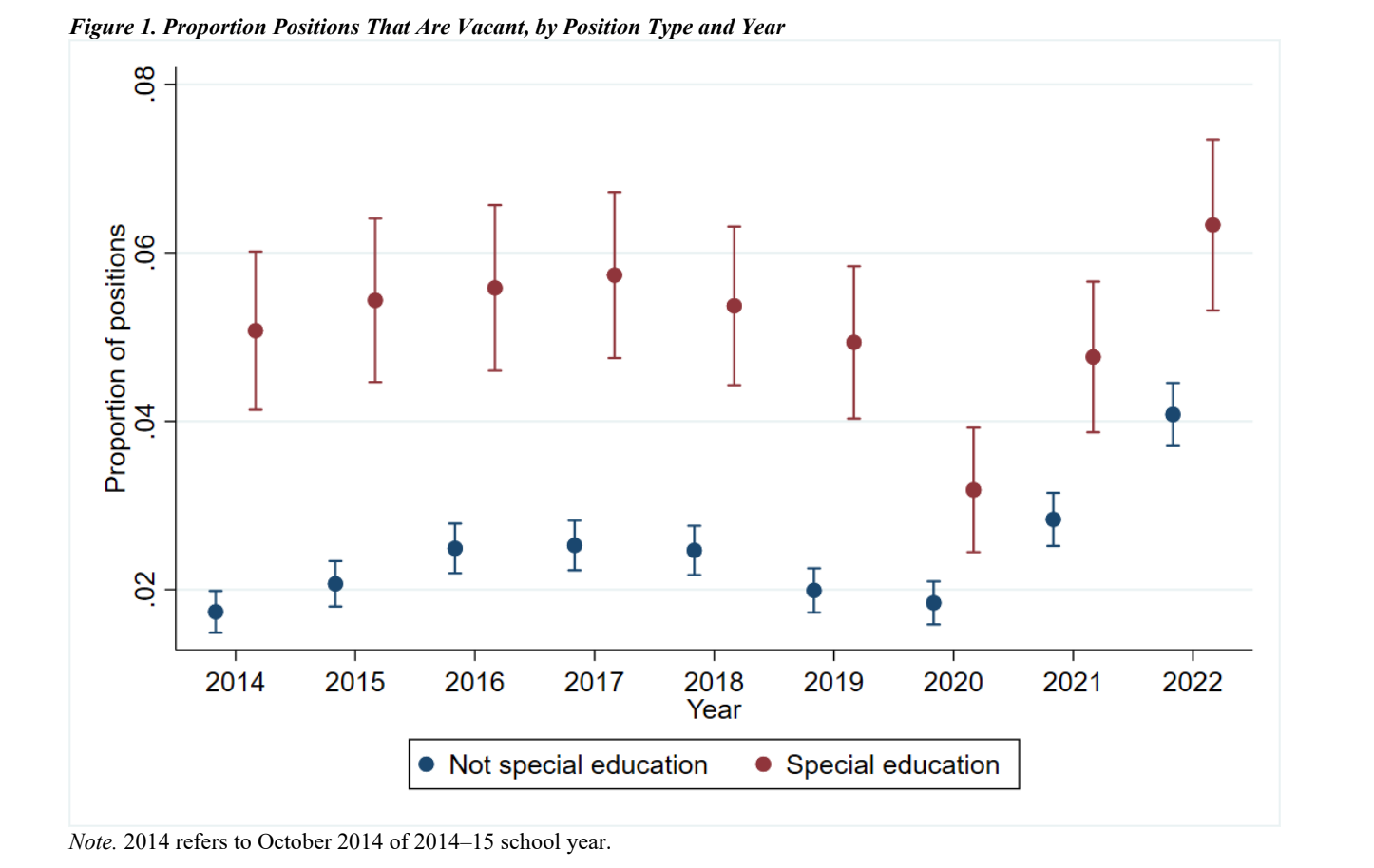

Theobald and his five co-authors at AIR and Boston University calculated that the pay hikes reduced the proportion of special education vacancies by a third. On the surface, that sounds like a success and other news outlets reported it that way. But special-ed vacancies actually rose over the study period, which coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, and ultimately ended up higher than before the pay hike.

What was reduced by a third was the gap between special ed and general ed vacancies. Vacancies among both groups of teachers initially plummeted during 2020-21, even though only special ed teachers were offered the $10,000. (Perhaps the urgency of the pandemic inspired all teachers to stay in their jobs.) Afterward, vacancies began to rise again, but special ed vacancies didn't increase as fast as general ed vacancies. That's a sign that special ed vacancies might have been even worse had there been no $10,000 bonus.

As the researchers dug into the data, they discovered that this relative difference in vacancies was almost entirely driven by job switches at hard-to-staff schools. General education teachers were crossing the hallway and taking special education openings to make an extra $10,000. Theobald described it as "robbing Peter to pay Paul."

These job switches were possible because, as it turns out, many general education teachers initially trained to teach special education and held the necessary credentials. Some never even tried special ed teaching and decided to go into general education classrooms instead. But the pay bump was enough for some to reconsider special ed.

Hawaii's special education teacher vacancies initially fell after $10,000 pay hikes in 2020, but subsequently rose again

(above, The dots represent the vacancy rates for two types of teachers. Source: Theobald et al, "The Impact of a $10,000 Bonus on Special Education Teacher Shortages in Hawai'i," CALDER Working Paper No. 290-0823)

This study doesn't explain why so many special education teachers left their jobs in 2021 and 2022 despite the pay incentives or why more new teachers didn't want these higher paying jobs. In a December 2023 story in Mother Jones, special education teachers in Hawaii described difficult working conditions and how there were too few teaching assistants to help with all of their students' special needs. Working with students with disabilities is a challenging job, and perhaps no amount of money can offset the emotional drain and burnout that so many special education teachers experience.

Dallas' experience with pay hikes, by contrast, began as a textbook example of how targeted incentives ought to work. In 2016, the city's school system designated four low-performing, high-poverty schools for a new Accelerating Campus Excellence (ACE) initiative. Teachers with high ratings could earn an extra $6,000 to $10,000 (depending upon their individual ratings) to work at these struggling elementary and middle schools. Existing teachers were screened to keep their jobs and only 20 percent of the staff passed the threshold and remained. (There were other reforms too, such as uniforms and a small increase in instructional time, but the teacher stipends were the main thrust and made up 85 percent of the ACE budget.)

Five researchers, including economists Eric Hanushek at Stanford University's Hoover Institution and Steven Rivkin at the University of Illinois Chicago, calculated that test scores jumped immediately after the pay incentives kicked in while scores at other low-performing elementary and middle schools in Dallas barely budged. Student achievement at these previously lowest-performing schools came close to the district average for all of Dallas. Dallas launched a second wave of ACE schools in 2018 and again, the researchers saw similar improvements in student achievement. Results are in a working paper, "Attracting and Retaining Highly Effective Educators in Hard-to-Staff Schools."

The program turned out to be so successful at boosting student achievement that three of the four initial ACE schools no longer qualified for the stipends by 2019. Over 40 percent of the high-performing teachers left their ACE schools. Student achievement fell sharply, reversing most of the gains that had been made.

For students, it was a roller coaster ride. Amber Northern, head of research at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, blamed adults for failing to "prepare for the accomplishment they'd hoped for."

Still, it's unclear what should have been done. Allowing these schools to continue the stipends would have eaten up millions of dollars that could have been used to help other low-performing schools.

And even if there were enough money to give teacher stipends at every low-performing school, there's not an infinite supply of highly effective teachers. Not all of them want to work at challenging, high-poverty schools. Some prefer the easier conditions of a high-income magnet school.

These were two good faith efforts that showed the limits of throwing money at specific types of teacher shortages. At best, they are a cautionary tale for policymakers as they move forward.