Sticker shock at the supermarket? These states have taken the biggest grocery price inflation hit

Sticker shock at the supermarket? These states have taken the biggest grocery price inflation hit

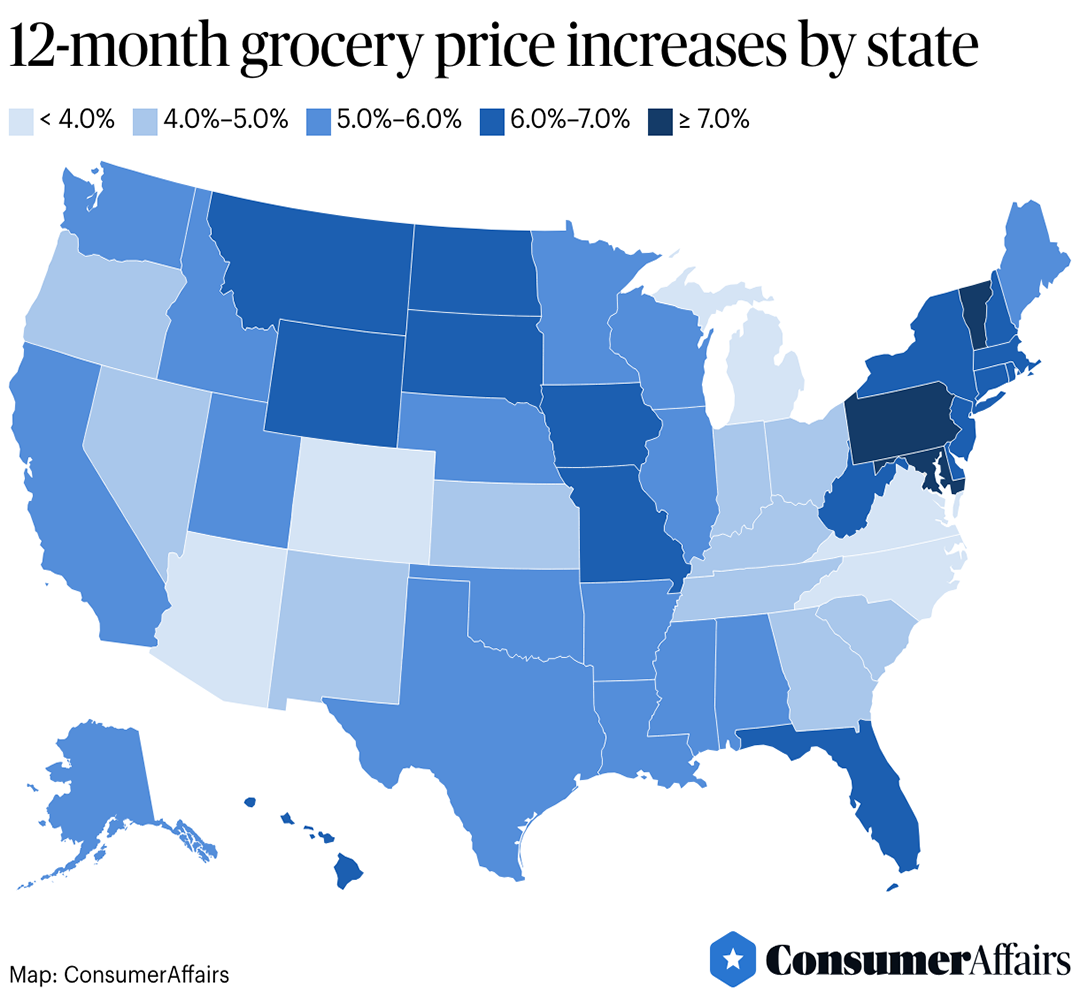

Grocery shoppers in every town and city know that the nation's food prices are higher than just a few months ago. But what remains hidden from American shoppers is that in some states, like Pennsylvania, prices have actually risen twice as fast as in others, like Colorado. What gives?

This is the topsy-turvy reality of local food prices that gets masked by nationwide inflation data and headlines.

A ConsumerAffairs analysis of grocery price data in 15 categories, collected in real time from 150,000 stores by partners at Datasembly, found that grocery prices increased 5.3% year over year. No surprise there. That's actually a dramatic improvement for grocery shoppers compared with the pace of food inflation in 2022. Going back two years, prices of those same goods have risen 25.5% nationwide.

The surprise is that in the past 12 months, grocery inflation has varied by as much as 5% from state to state. In dollars and cents, that means where you live could make a $500 a year difference for a family of four that spends $750 a month on groceries, enough to drive a sizable number of Americans to take on new debt.

Similarly, some metro areas have had far higher grocery price inflation than others. Orlando, Florida, ranks in the top six metros in terms of grocery hikes, with an average increase of 6.5% in 12 months. That's more than twice the increase felt by grocery shoppers in Richmond, Virginia, or San Diego.

It takes a toll. Beth Nicholas, of Sanford, Florida, near Orlando, says she has noticed that prices of everything have gone up in the last year, often by $1 or more. Sometimes, she says, the increase is a lot more – for beverages especially.

"A case of Diet Coke has gone from $7.88 to about $12.88, and that's at Walmart," she told ConsumerAffairs. "And candy is a lot more expensive. A bag of Dove chocolates used to be about $4 and now it's over $6."

The disparity between states with high and low price increases is significant

As of mid-November, the states seeing the largest increase in these prices are clustered in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states.

- Pennsylvania: 8.2%

- Vermont: 7%

- Maryland: 7%

- West Virginia: 6.9%

- New Jersey: 6.8%

- Massachusetts: 6.6%

- Connecticut: 6.4%

- Florida: 6.4%

- Montana: 6.4%

- South Dakota: 6.4%

- North Dakota: 6.4%

- Iowa: 6.4%

The states with the lowest grocery price hikes are located all over the map, but over 12 months their price hikes were barely half as large as Pennsylvania's.

- Colorado: 2.9%

- Arizona: 3.3%

- North Carolina: 3.5%

- Michigan: 3.5%

- Virginia: 3.6%

- Nevada: 4.2%

- South Carolina: 4.3%

- Indiana: 4.4%

- Ohio: 4.4%

- Oregon: 4.5%

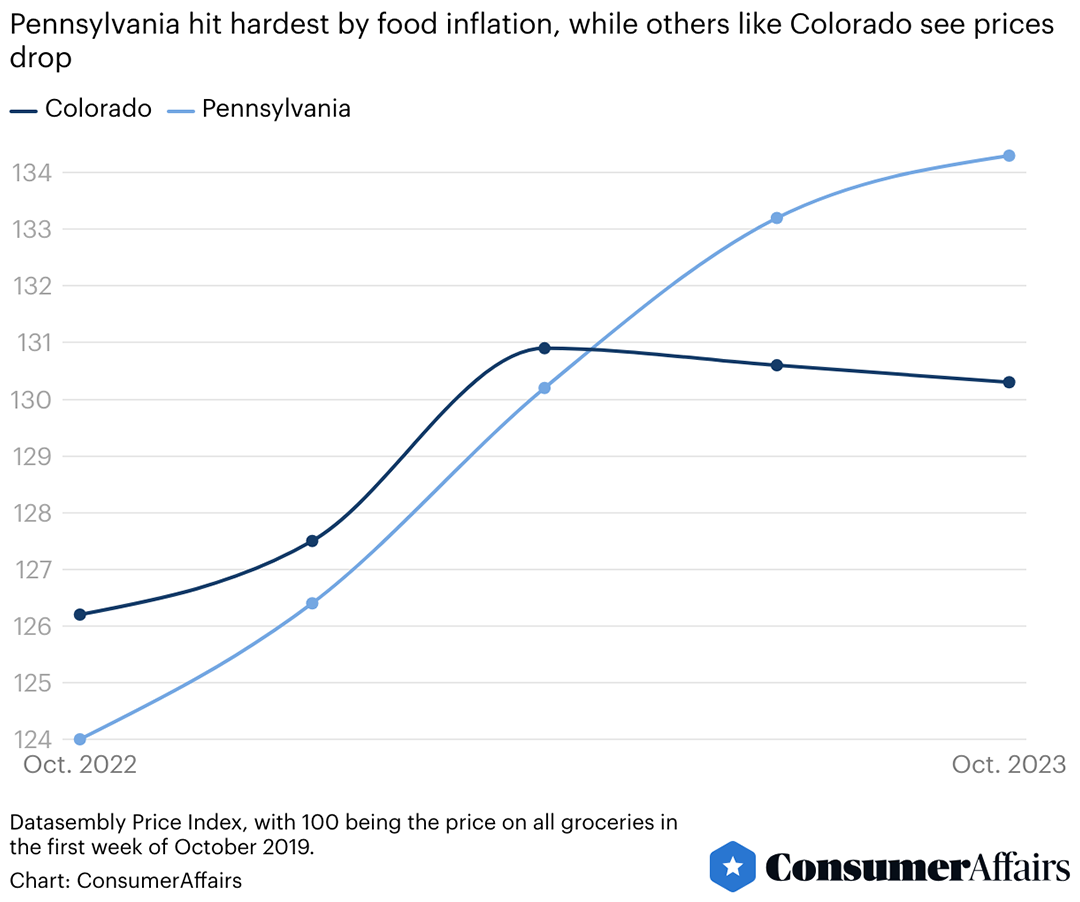

A tale of two states

In Pennsylvania, prices in the 15 grocery categories analyzed are up 8.2% in the last 12 months, the nation's highest hike. In Colorado, meanwhile, the prices of those same product categories are up just 2.9%.

A Colorado family of four that spends an average of $750 a month on groceries saw their food bill rise by $21.75 a month in 12 months. A Pennsylvania family of four spending the same amount is forking over an extra $61.50 a month, for a difference between the two families of $477 over the course of a year.

The data shows that price hikes in individual grocery categories, often completely independent of each other, range widely nationally and locally.

The war in Ukraine, for example, has reduced shipments of wheat, which has affected the prices of everything from bread and crackers to cereal.

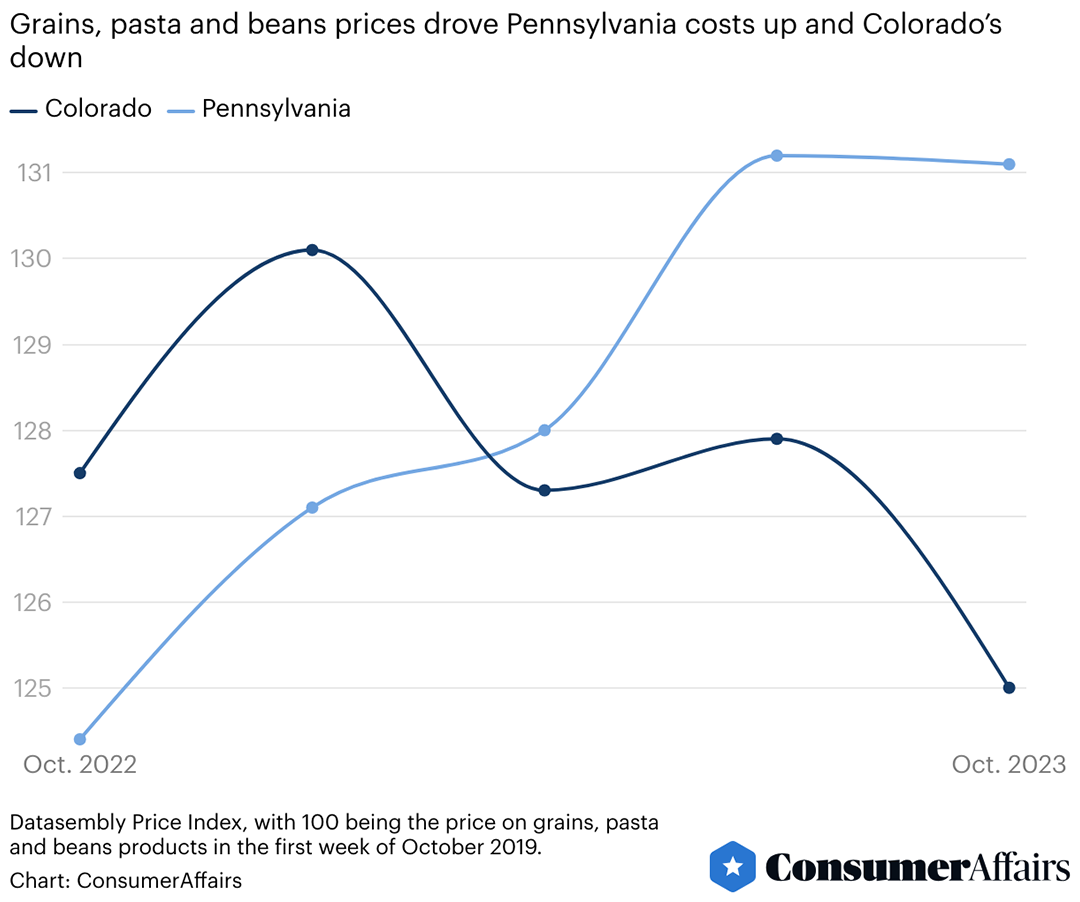

Are there any product categories that help explain the large differences in grocery inflation between Pennsylvania and Colorado? One stands out.

Nationally, prices for grains, beans, and pasta are up 1.5% over 12 months. Yet in Colorado those products actually went down in price and are nearly 2% cheaper than a year ago, helping to explain the state's low food inflation.

A year ago, the prices a Pennsylvania shopper paid for grains, beans, and pasta products were rising slower than those paid by the average Colorado shopper. But with those prices in the Keystone State rising by 5.3%, faster than the national average, the lift in costs is now far faster than in Colorado.

Why price inflation varies in different states and cities

Julie Companey, director of client strategy in the grocery industry for Vericast, said it's often hard to determine why price hikes for the same product vary in different markets. The explanation can be buried in a region's average grocery store operating costs or how different chains get a product to their stores.

"Reasons include the differences between supply chain and overhead expenses," she told ConsumerAffairs. "Like local labor, utilities, tax, and real estate costs."

George Davis, professor of agriculture and applied economics at Virginia Tech, believes that sometimes the explanation goes back to basics: supply and demand.

Large cities with large populations produce added demand. Higher salaries in an area make it easier for some stores to charge higher prices. "In general, food prices tend to be higher in the Northeast and the West," Davis told ConsumerAffairs. "The basic reason is more population density and incomes."

If it were that simple, however, dense big cities like Los Angeles, Chicago, or Dallas would have the fastest grocery inflation. That is not the case. All three cities had their grocery prices rise at about average rates this year.

One reason: Density creates more stores competing for business, which can counteract a region's high incomes and keep prices in check. "Retailers track competitive pricing and promotions and adjust their own to deliver their desired value proposition to their customers in each market," Companey said. "One of the most influential factors is the level of competition."

Davis says urban and suburban grocery chains must go out of their way to scale supply to compete. Supermarkets in the city and suburbs tend to be much larger and carry a wider assortment of products and can settle for a smaller profit margin.

"The larger the store, its cost of providing groceries is lower per unit," Davis said. "Also, by diversifying the products they sell, they get what's called economies of scope."

Are rural areas paying more?

Grocers in rural areas, on the other hand, lack competition. The result: Grocery price inflation for rural shoppers ran 7.6% in the past 12 months, compared with only 5.6% for residents of large cities.

Rural grocery prices historically tend to be higher than elsewhere. Companey says many grocery stores in rural areas are usually supplied by wholesalers instead of buying directly from manufacturers, which adds a layer to the supply chain and lifts transportation costs.

Rural areas also tend to be lower in household income, which counterintuitively can be tied to higher grocery price hikes, due to the lack of grocers attracted to poorer areas. Datasembly found that the biggest rise in grocery prices over 12 months came in ZIP codes where the average income is $35,000 to $50,000, the lowest band it tracks. Price inflation there was equal to those in the highest-income ZIP codes in America.

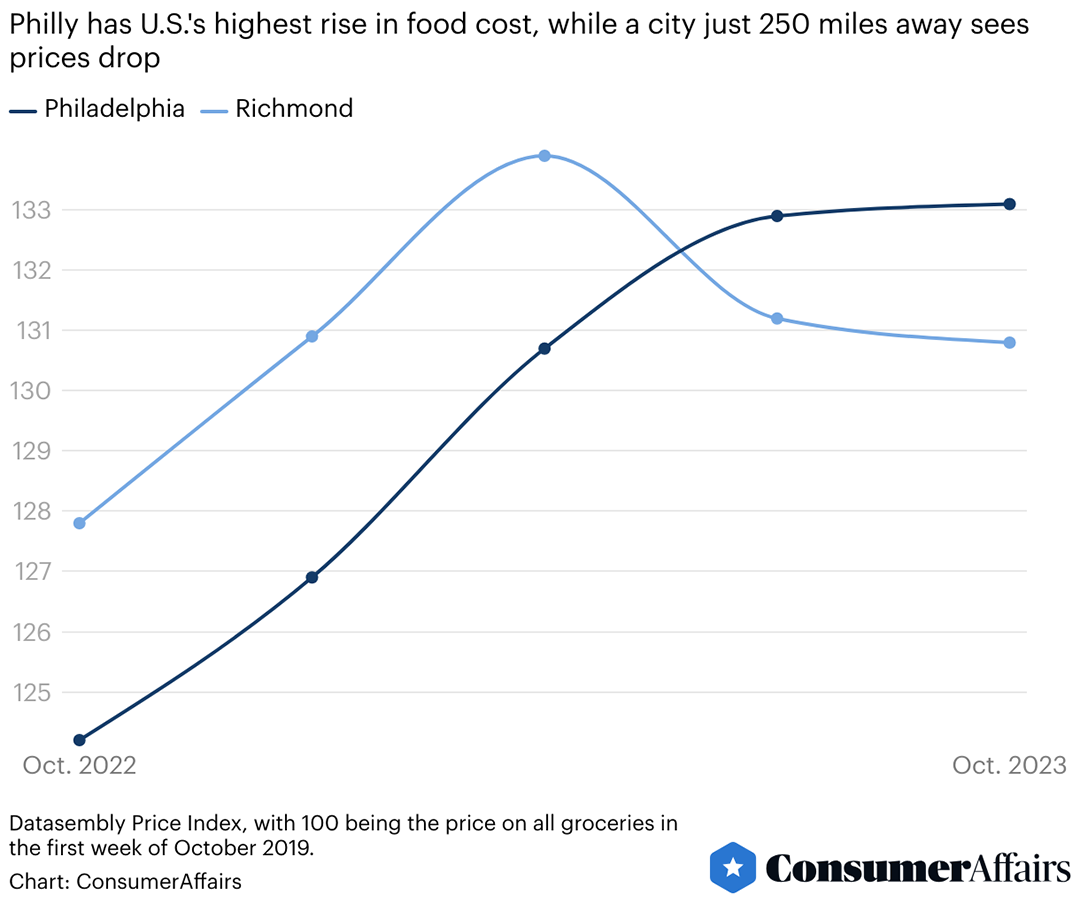

A tale of two cities

Grocery cost hikes vary even more widely between metro areas. Philadelphia had among the nation's highest grocery price increases this year, while Richmond, Virginia, 253 miles down Interstate 95, had among the nation's lowest.

In Philadelphia, prices across the 15 categories analyzed have increased by 7.1% over the last 12 months. In Richmond, the cost is up just 2.3%, well below the national average of 5.3%.

A family of four in Philadelphia spending $9,000 a year on these grocery items is now spending $645 more than a year earlier. In Richmond, that same family would spend an extra $218.

Philadelphia shoppers who buy grain, beans, and pasta are paying 3.7% more than a year ago, and the price of meal solutions (those pre-made meals prepped by grocers for dining at home) has risen 5.1%. The prices paid by Richmond shoppers have actually dropped 2.5% year over year for grains, beans, and pasta and 2.1% for meal solutions.

There is also a serious divergence when it comes to beverage inflation. In Philadelphia, the annual increase in beverage prices was 6.1%. In Richmond, beverage prices increased by less than 1%.

Metros that experienced the largest price increases over the last 12 months are:

- Philadelphia: 7.4%

- Albany, N.Y.: 7.2%

- Syracuse, N.Y.: 7.1%

- Baltimore: 7%

- Boston: 6.7%

At the other end of the scale, grocery prices have risen just 2.3% in Richmond, Virginia, and 3.3% in San Diego.

A tale of two foods

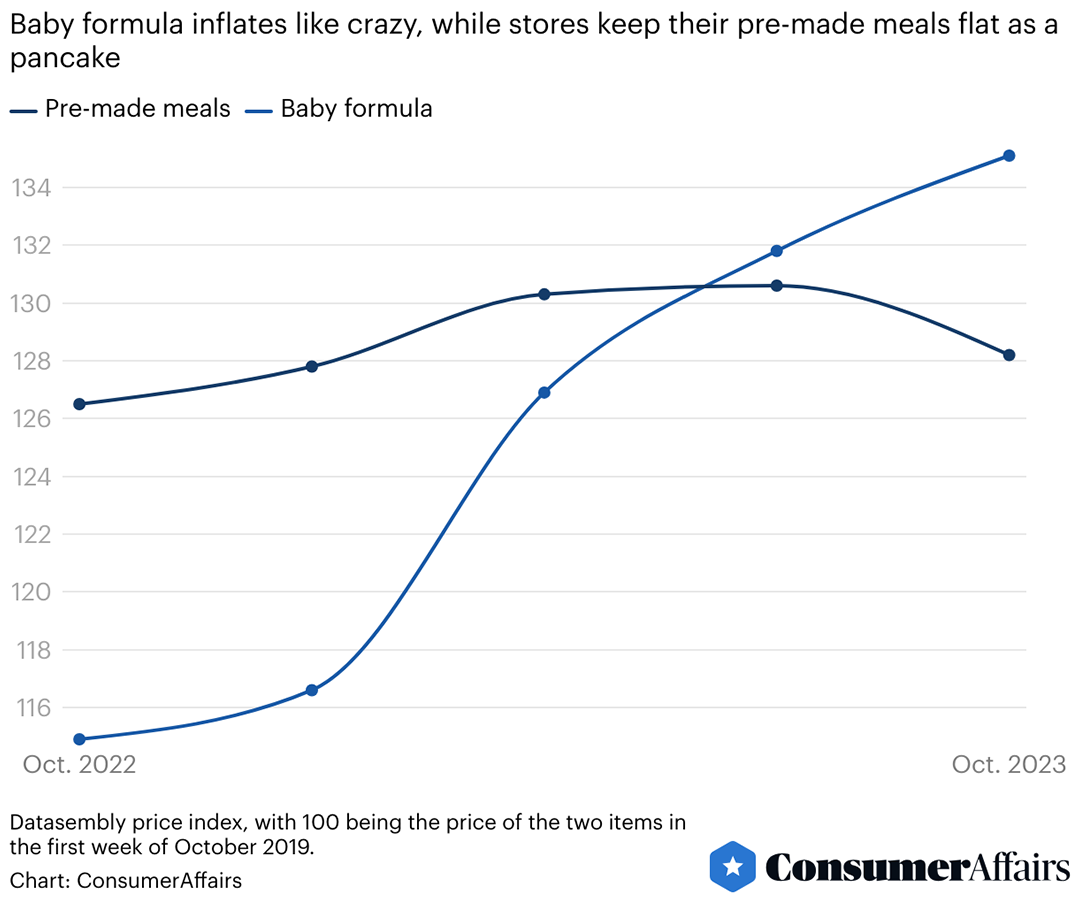

Consumers looking for tangible ways to manage their money can often reduce the burden of inflation by adjusting their menu, substituting a less expensive food for a more expensive one. But sometimes that can't be done. For example, a family with a newborn may have to purchase infant formula.

Unfortunately, the price of infant formula has risen more than any other grocery category over the last year, costing 17.5% more than a year ago. The price began to rise in early 2022, when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), working with plant owner Abbott Labs, closed a major infant formula plant for months because of potential contamination.

Compared with meal solutions, the category with the lowest price inflation, the contrast can be startling, ConsumerAffairs found.

Noticeable to anyone with a sweet tooth, the cost of candy and gum has also registered a double-digit increase nationally, rising 10.7%. Beginning in April, rising sugar prices began to pick up speed.

The price of pet food is up 8.2%, the cost of baby food has risen 7.5%, cookies and crackers cost 6.6% more, beverages are up 6.5%, and cereal prices are 5.4% higher — all larger increases over 12 months than the inflation rate for groceries generally.

Grocery categories included in the analysis are below. They're listed from the biggest 12-month price change to the smallest between October 2022 and October 2023.

- Baby formula: (17.5%)

- Candy/gum: (9.7%)

- Pet food: (8.5%)

- Cookies/Crackers: (+6.6%)

- Beverages: (+6.5%)

- Seasonings/Sauces: (+5.7%)

- Snacks: (+5.6%)

- Condiments/Spreads/Dressing: (+5.2%)

- Fruit/vegetables: (+4.9%)

- Cereal: (+4.8%)

- Baby food: (+3.6%)

- Bakery: (+3.4%)

- Baking: (+3.4%)

- Grains/Beans/Pasta: (+1.5%)

- Meal solutions: (0%)

What consumers are noticing

Linda Quilter and Becky Merriman, two consumers in rural eastern Virginia, have certainly noted some items have risen more than others.

"Beverage prices are much higher," Merriman told ConsumerAffairs. "I think I paid close to $10 for a 12-pack of ginger ale. Paper plates are also a lot more expensive."

According to Datasembly, beverage prices are up just 1% in Virginia. However, they may be more expensive in Merriman's area because it is served by only two supermarket chains.

"The price of bag salads has gone out of sight," Quilter added, noting that bacon is still pretty high where she shops. In Virginia, produce prices are up 3.8%, compared with 4.9% nationwide.

Watchdogs have a word when grocery providers raise prices beyond inflation: "greedflation." Scott Lieberman of Touchdown Money advises greedflation-whacked consumers to hunt out cheaper substitutes. "As much as I love Oreos," he told ConsumerAffairs, "now that they've raised the price so much, I've switched to the generic supermarket brand cookies that are similar."

When grocery inflation disrupts your family budget

Even savvy shoppers who switch to store-brand foods are challenged by today's prices. Credit card and other consumer debt is at an all-time high and rising grocery costs are a primary reason. To manage, the editors at ConsumerAffairs advise:

Eat at home more often, not less. Even in an inflationary era, planning for more meals at home will save money over time. Just a few meals a week from restaurants, even takeout, can drive the family food budget into the red. Smarten your shopping with detailed meal planning so you can stick to the list at the market, avoid impulse buys, and build meals around lower-cost or sale items or those with coupons.

Limit the daily debt damage. Using a credit card to pay for weekly market trips or monthly hauls of staples is better than not feeding your family. The key is to plan ahead how to escape the debt treadmill. Can you transfer all or part of the balance to a credit card with a 0% introductory rate? Can you convince your auto and homeowners' insurance companies to lower your rates so you need your credit cards less often? When will it be worth it to get help or a debt management plan?

Wherever you live, grocery inflation is now a fact of life, but nothing that a thoughtful household can't deal with directly.

This story was produced by ConsumerAffairs and reviewed and distributed by Stacker Media.