Despite lower diagnosis rates, Black men are more likely to die from melanoma

This story originally appeared on Northwell Health and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Despite lower diagnosis rates, Black men are more likely to die from melanoma

Skin cancer diagnosis rates are on the rise across the developed world. Between 1975 and 2018, American melanoma incidence rates more than tripled from 7.9 to 25.3 cases per 100,000 people, according to a study published in 2021; today, melanoma represents the fifth-most common type of cancer in the country. The reasons for this increase are wide-ranging, from longer life spans to increased ultraviolet radiation exposure.

While more people have been diagnosed with melanoma, patients with this type of skin cancer are facing increasingly better survival odds overall. Since 2013, the death rate from melanoma among all patients has fallen by more than a quarter, per data from the National Cancer Institute. Approvals in the last decade for novel treatment methods for advanced cases of melanoma, such as immunotherapy, are contributing to the overall improving survival rates.

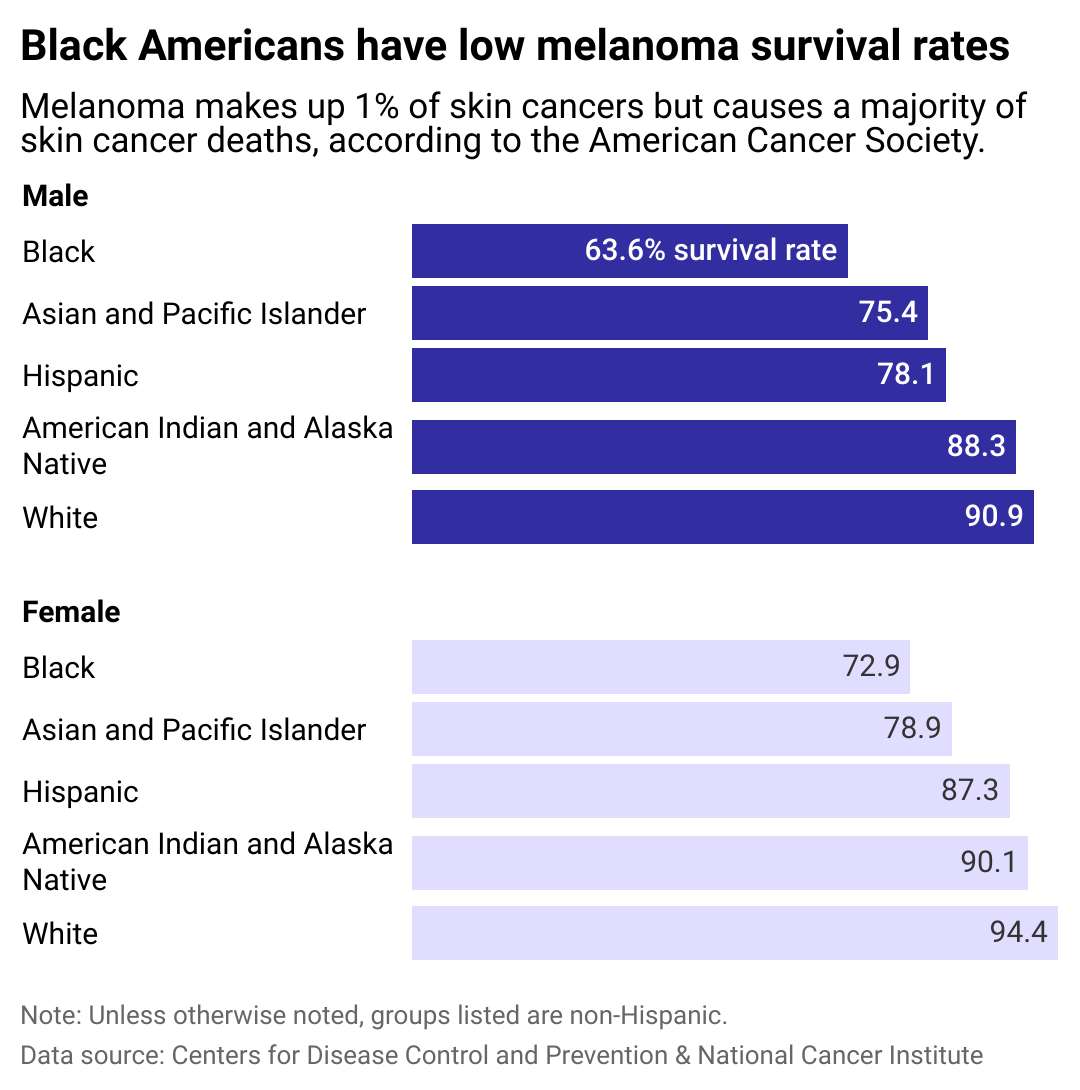

But as is true with other health outcomes, mortality rates vary significantly among racial and ethnic groups in the country. Black Americans have a 26% higher risk of death from melanoma than white Americans, according to a study released in July 2023, with Black men experiencing the lowest survivability rate of any racial demographic despite having lower rates of diagnosis.

Northwell Health examined data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Cancer Institute to show how melanoma diagnoses and survival rates vary by race and sex.

Exposure to UV radiation from the sun (or by artificial means, such as tanning beds) is among the leading risk factors for developing melanoma. The strength of UV rays varies by location, with the highest intensity measured around west-central South America. While our planet's ozone layer helps to block harmful UV rays emitted by the sun, UV damage can occur anywhere the sun shines—and depleted ozone from the use of chemicals such as those found in refrigerators, air conditioners, aerosols, and other commonly used products can make UV radiation more intense. According to the World Health Organization, just a 10% reduction in the ozone layer accounts for an additional 4,500 cases of melanoma, making human-caused ozone depletion a contributing factor to increased incidences of the disease. For Black people and others with darker skin, however, melanoma is not linked to sun exposure, according to the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Keep reading to learn more about variations in melanoma diagnoses, how survival rates in the U.S. are affected by race and sex, and how Black men are disproportionately vulnerable.

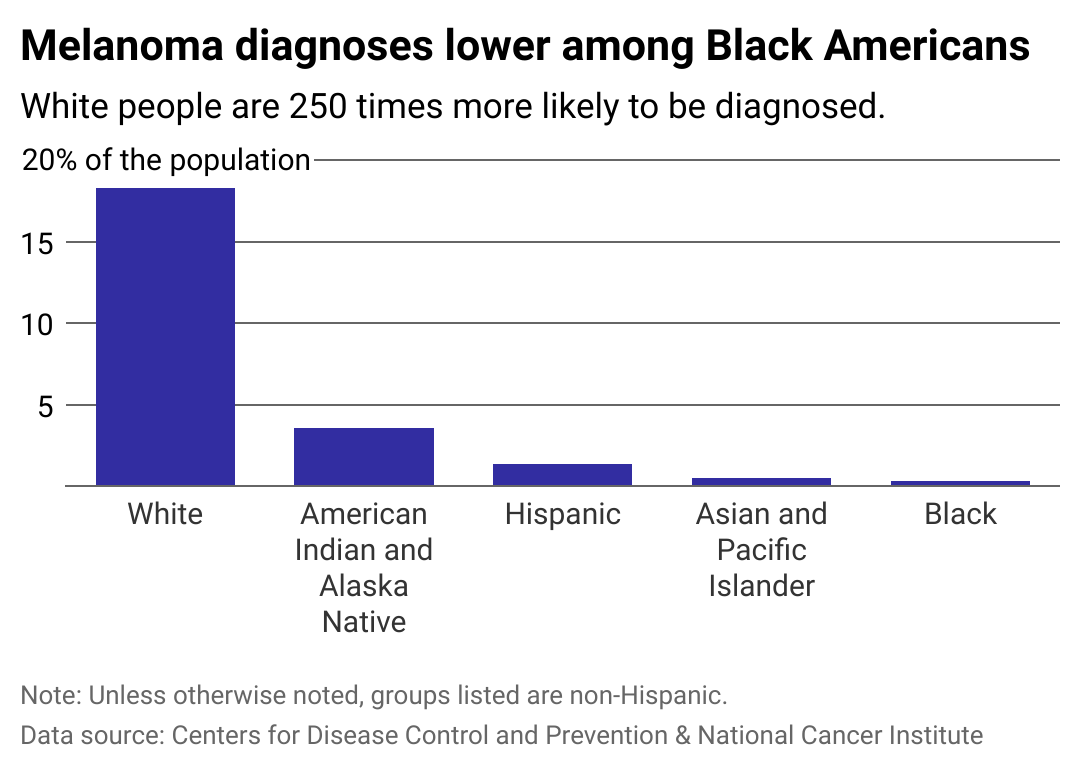

Black Americans less likely to be diagnosed with melanoma

Melanin, a color pigment found in skin, eyes, and hair, acts as a natural sunscreen by scattering UV radiation, which prevents its penetration into the skin—but it does not altogether remove one's risk of melanoma.

Research shows that melanin in Black individuals allows for three times less UV radiation than in white individuals, resulting in just 1 in 10 Black people experiencing at least one sunburn in a year compared to one-third of Hispanic people and two-thirds of white people, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The type of melanoma most common among Black people, acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM), actually occurs on parts of the body with the least sun exposure. According to a 2019 study in the Preventing Chronic Disease journal, the nail beds, soles of feet, and palms of the hands are where most incidences of melanoma in Black people occur. This subtype of melanoma is also deadlier, with lower survival rates than the most common types of melanoma among white people.

Because many people—including doctors and the medical community at large—lack the education and experience to identify melanoma on dark skin, Black Americans with this form of cancer often go untreated for longer than their white counterparts.

Black Americans also have lower survival rates

Because melanoma among Black communities and other communities of color is often not caught early—whether due to a lack of self-inspection or screenings from doctors, barriers to health care, or other factors—the cancer is often more advanced when it is diagnosed, making standard treatments far less effective.

A survey published in 2023 revealed that public melanoma awareness messaging fails to speak to Black people and that patients in this racial group tend to underestimate their lifetime risk of developing skin cancer. The disparities in diagnoses and survival rates make clear the stark need for communities of color to be appealed to with awareness campaigns that clarify the risks and advise people to pay close attention to vulnerable parts of the body for this demographic, such as nail beds and palms.

How to detect skin cancer early

Early detection significantly improves the likelihood of curing melanoma. Regular dermatologist visits can help with detection, but the American Cancer Society also recommends monthly self-examinations. These can be performed in a well-lit room, using mirrors to inspect hard-to-see areas. Checking the skin on the lower body, such as the buttocks, lower legs, and the bottoms of the feet, for changes is especially important for people with darker skin.

Melanoma often manifests as new moles, sores, lumps, blemishes, or changes to existing body marks in appearance or texture. It manifests on Black peopels's skin, and on other people with darker skin, as darker patches of skin or dark lines underneath the nails. Physicians advise scheduling an appointment with a dermatologist if any of these signs are discovered.

Public health education, early detection, and access to treatment are all essential components of reducing mortality rates among the general population—and in particular in Black communities.

Story editing by Nicole Caldwell and Kelly Glass. Copy editing by Tim Bruns.