Health care inflation remains low as other services continue to spike

This story originally appeared on Vivian Health and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Health care inflation remains low as other services continue to spike

If filling up your tank or getting your groceries in 2023 were any indication, the dollar hasn't been stretching as far as it used to. Since 2000, prices for consumer goods and services in the U.S. have risen by just over 80%—however, medical prices have increased by nearly 115%.

It's no secret health care in the United States is among the costliest in the world, but there's some good news: Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index data released in October 2023 reported that prices for consumer goods and services rose 6% from February 2022 to February 2023, while the cost of medical services grew just 2.1% over the same period.

Health insurance costs fell from a peak in September 2022 by about 3% to 4% a month, mirroring a decrease in insurers' profits when people began using health services again. There had been a steep drop in 2020 when medical practices were largely closed, but insurers pocketed premiums all the same.

The major events of the past few years, like the COVID-19 pandemic and worsening geopolitical conflicts, played a large part in overall inflation in 2023.

Vivian Health used data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, news coverage, and research studies to analyze health care costs year-over-year and the ways that health care inflation differs from other consumer goods and services.

Measuring inflation isn't always straightforward

Complications in the supply chain for items like semiconductors were profound during the height of the pandemic. Car manufacturing paused when automakers couldn't get their hands on chips that provide key features due to factory or logistics closures and increased demand for computers to service the swift shift to remote working. The Russia-Ukraine war also put additional pressure on the global energy market and food costs, which reverberated throughout the U.S. economy.

More recently, price increases for gasoline and cars have slowed. But even when the market cools off, health care inflation rates tend to remain elevated and continue to rise incrementally, according to a Money interview with HealthView Services CEO Ron Mastrogiovanni.

Health insurance costs are expected to bounce back up and have begun rising 1% each month since October 2023, according to a CNBC interview with Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody's Analytics.

The way economists measure inflation, though, depends on how they slice it. The CPI's measurement of health insurance inflation, in particular, isn't an exact science. It only shows a picture of how prices for consumers change.

For instance, since health insurers don't provide health plans of equal quality, the BLS measures health insurance inflation using health insurers' profits instead of trying to weigh the benefits and risk factors that vary across policies. Also, Medicaid and workers' compensation payments aren't factored into the CPI, since consumers don't need to pay out-of-pocket to participate.

Measuring inflation for other costs, such as those included in the Personal Consumption Expenditures price index, is more straightforward. It involves examining how much consumers, their employers, and the government pay for specific goods and services.

Inflation for services and what it means for health care

The pandemic precipitated medical staff shortages. Large numbers of health care employees quit from burnout or frustration, or retired. During this time, many staff nurses left to work as traveling nurses, allowing them to earn more money in places where help was needed most.

By 2025, researchers at the McKinsey consulting firm expect a 10% to 20% labor shortage in registered nurses and 6% to 10% for doctors. As a result, compensation for health service workers has increased by 4.9% since last year. In addition, growing evidence shows that as more hospitals and health systems merge across markets, there could be fewer places for people to receive health care. Experts know consolidation that lessens competition also results in higher prices.

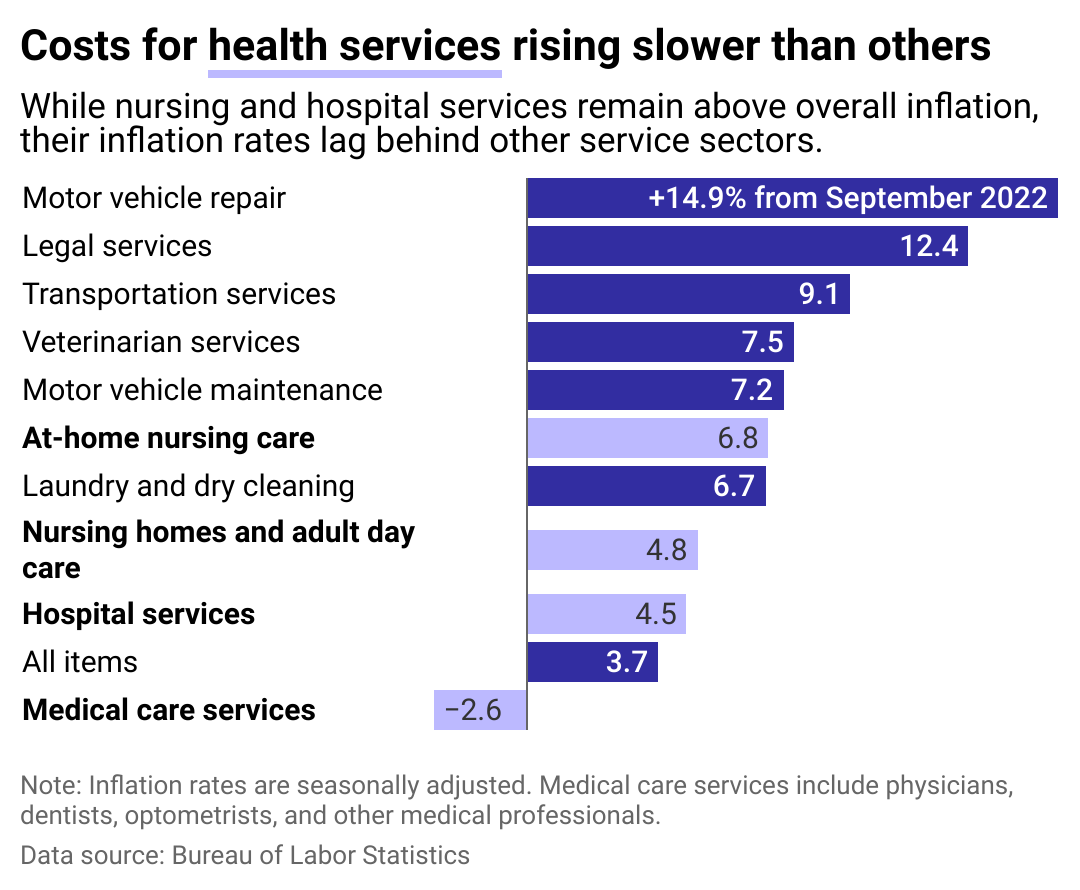

These factors are compounded by an aging population in the U.S. that will soon deplete Medicare's Hospital Insurance Trust Fund. The BLS found that at-home nursing care, nursing homes and adult day care, and hospital services costs are still rising—by 6.8%, 4.8%, and 4.5% respectively.

In particular, high prices mean competition for long-term care placements that accept Medicaid is also high. Only 18% of residential care centers and 62% of nursing homes take Medicaid, and the residents must be both frail enough to qualify and have very little money. Some facilities have yearslong waiting lists, reports the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Paying privately for elder care is also beyond the reach of many Americans, with assisted living costs increasing 31% faster than inflation. One spokesperson from a facility that charges $750 per month to make sure residents take their daily medicine explained that "the cost and complexity of providing care and housing to seniors has increased exponentially due to the pandemic and record-high inflation," according to New York Times reporting.

So while the success of the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act may help put downward pressure on the sky-high costs of prescription drugs—at least for Medicare enrollees—there's still a lot of work to be done to ensure many Americans can afford the health care they need.

Story editing by Jeff Inglis. Copy editing by Tim Bruns.