How adolescent substance use treatment has changed over the past 70 years

This story originally appeared on Sandstone Care and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

How adolescent substance use treatment has changed over the past 70 years

A "one size fits all" philosophy doesn't work for substance use treatment, particularly when comparing adolescents to adults.

Teens who misuse substances tend to be focused on their immediate problems, are prone to bingeing and peer pressure, and have more instances of multiple psychiatric disorders than adults. Teens also are less inclined to believe they have a substance abuse problem, according to Current Psychiatry Reports.

Sandstone Care explored data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and other research to look at how adolescent substance use disorder treatment has evolved over time and where it's available now.

In 2022, reports of illicit drug usage were at or below levels from before the COVID-19 pandemic after the pandemic nosedived adolescent use of drugs and alcohol, according to the annual Monitoring the Future survey from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

While substance use hasn't increased, the number of overdose deaths has skyrocketed, likely due to the increase of fentanyl in other drugs. Overdose deaths more than doubled among 14- to 18-year-olds, from 2.36 deaths per 100,000 in 2019 to 5.49 deaths per 100,000 in 2021, according to a study by UCLA and Harvard health scholars published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

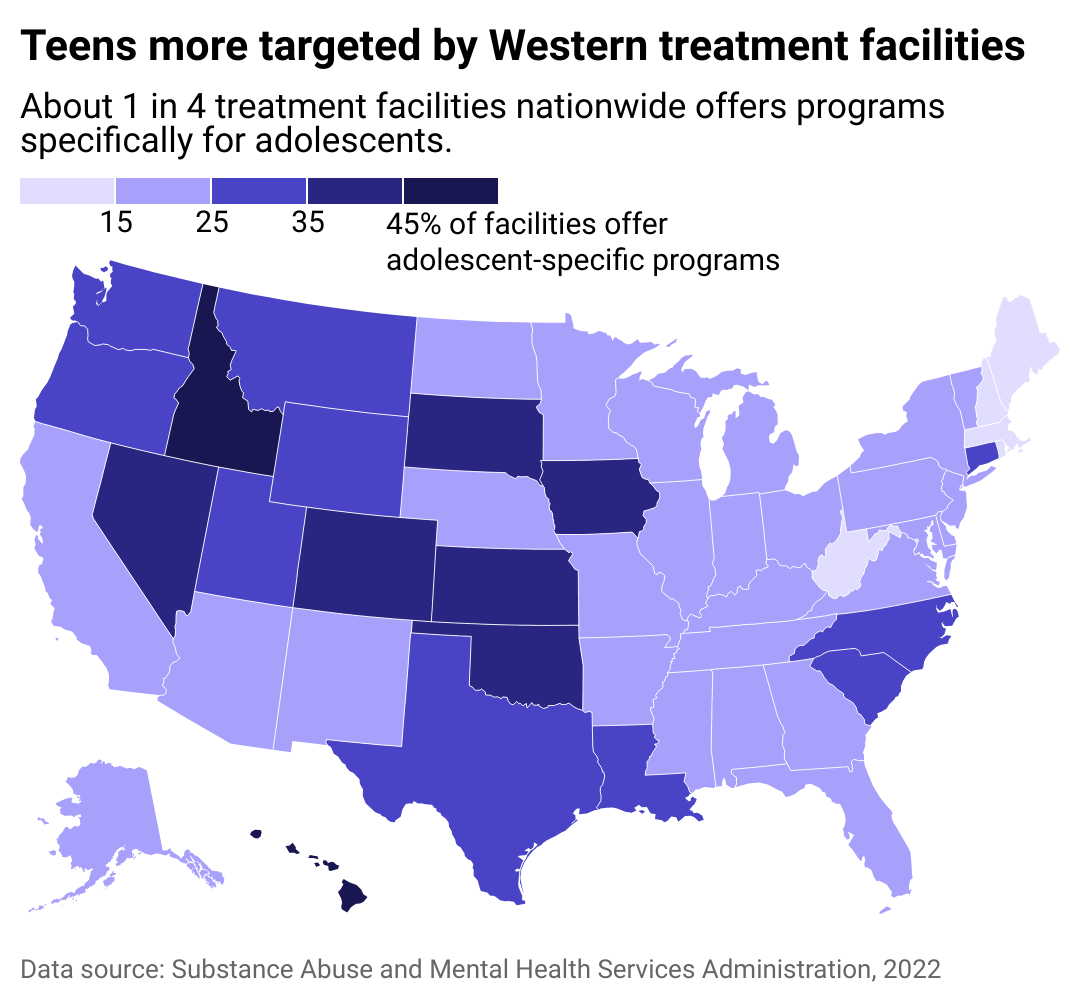

A small population of those who use drugs and alcohol will develop use disorders, which are a compulsion to continue using drugs or alcohol even with negative consequences. But of the nearly 15,000 treatment facilities in the United States, less than 25% of them offer programs specifically for adolescents.

Targeted treatments for adolescents began in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, according to "A Brief History and Some Current Dimensions of Adolescent Treatment in the United States." Interest in treatments grew around World War I after the military rejected thousands of drafted men addicted to heroin.

Teens started receiving specialized treatment in the 1950s when hospitals and churches noticed that substance use disorders manifested differently in younger users. In 1952, New York City's new Riverside Hospital became the first substance use disorder treatment center for adolescents. However, most adolescents still received adult-centered treatment through the 1980s until research disproved these methods.

Today, well-established, evidence-based treatment for adolescents, according to a 2019 paper in Current Psychiatric Reports, includes the following.

- Family-based therapy, which works with parents, siblings, and caregivers.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy, which teaches adolescents how to respond differently to their thoughts and behaviors.

- Multicomponent psychosocial therapy, which combines several other therapies into one treatment plan.

These specific treatment plans are needed because teenage brains are still developing—they won't fully mature until they reach their mid-20s—and are more malleable than adults' brains, according to the journal Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics.

At this stage of neurodevelopment, teens' brains want pleasure, but their ability to assess risk and make good decisions is not as well-developed. Curiosity about alcohol or drugs may lead to use, and during teenage years, substance use may alter vital neural circuits that are still developing.

Where adolescent-focused treatment is most available

Addiction research suggests teens experience fewer withdrawal symptoms than adults, lowering the need for age-focused withdrawal treatment. Opioids and fentanyl are changing the game, though, making withdrawal more difficult, even in teens.

However, there's not much assistance out there for teens who need specialized treatment centers to help them with withdrawal. According to KFF Health News, just 63 of the 160 adolescent residential treatment centers they contacted offered on-site detoxing, and fewer offered access to buprenorphine, a drug that helps treat withdrawal. Just one site—Denver Health—had an adolescent inpatient detox unit.

With so little specialized help, many teens' families are left to seek assistance where they can get it, even if it's not the best care. They may have to call dozens of treatment centers before finding one that offers medication-assisted treatment and suffer more than medical research indicates they need to. That makes teens more vulnerable to stopping treatment and returning to their addictions. And members of marginalized communities, such as people from families with lower income or racial or ethnic minorities, are at even more risk of treatment failure.

The CDC is putting more attention on substance misuse in adolescents because these behaviors could lead to many future health and well-being problems. While it won't provide immediate help, the American Society of Addiction Medicine is revising its standards for opioid use disorder treatment in young people in 2024, which may provide the impetus for more teen-focused treatments.

Story editing by Jeff Inglis. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.