States are enacting laws this year to put opioid overdose remedies in more public places

This story originally appeared on Ophelia and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

States are enacting laws this year to put opioid overdose remedies in more public places

Twenty-two high school-aged Americans died of a drug overdose each week in 2022. Their deaths were preventable, and lawmakers around the country are passing laws requiring overdose reversal drugs in more public places, challenging the stigma of drug use.

Ophelia analyzed new state legislation tracked by the National Conference of State Legislatures to illustrate how lawmakers are placing lifesaving overdose drugs where they can make a difference.

Opioids were involved in 75% of all overdose deaths in 2021 (the latest CDC data). And synthetic opioids, specifically fentanyl, have played a part in the majority of those overdose deaths, according to the CDC.

Studies have shown that some teens aren't necessarily seeking out dangerous synthetic opioids like fentanyl. Instead, driving the epidemic of drug overdose deaths are other illicit drugs laced with fentanyl, often unbeknownst to the people taking them.

"Some kids experiment with substances, unaware that just one counterfeit pill can contain enough fentanyl to be fatal," pediatrician and Washington State's chief science officer Tao Sheng Kwan-Gett said in a notification earlier this year, encouraging the availability of naloxone in public high schools.

In a letter to educators around the start of the 2023-24 school year, the White House urged schools to "focus on measures to prevent youth drug use and ensure that every school has naloxone and has prepared its students and faculty to use it."

It came on the heels of an American Medical Association notice urging schools to keep naloxone on hand. Departments of health in some states, like Indiana, are also using public messaging to combat the misguided belief that naloxone promotes risky drug use by providing a way to reverse overdoses.

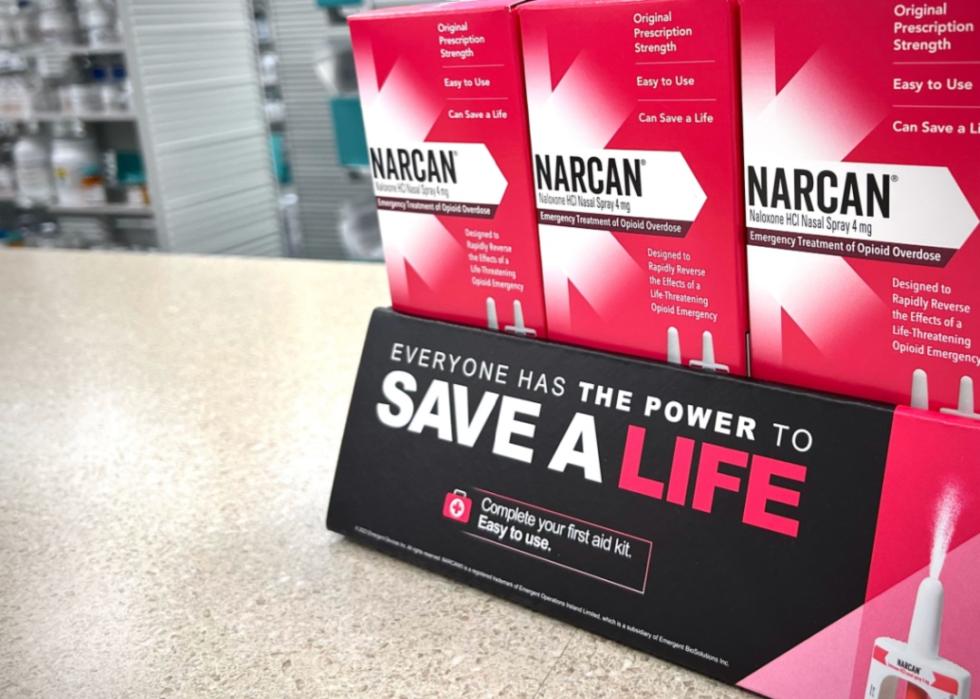

Many legislatures are now placing circumstance above stigma, having proposed or enacted 126 laws related to opioid overdoses in 25 states over the last year. Common among the laws passed recently are authorizations allowing school nurses to stock overdose reversal drugs in public schools and public places like concert venues.

Because opioid use in youth follows the same patterns as opioid use disorder in adults, according to a 2022 study in the Journal of Adolescent Health, newer policy addressing the opioid epidemic affecting the approximately 2.5 million adults over age 18 looks to tackle it where it starts.

Recruiting school nurses

School nurses are on the front lines of the battle against the opioid epidemic affecting young people—often the most accessible day-to-day health professionals for children. Their work is crucial: A 2017 study in the Addiction Science & Clinical Practice journal showed that the younger a person begins using opioids, the higher their risk of having a physical or psychiatric injury.

The National Association of School Nurses, representing around 19,000 professionals, has endorsed stocking naloxone in schools since 2015. States, including Oklahoma and Arkansas, have expanded access to these medications in K-12 schools. A Georgia bill authorizing schools to stock and use naloxone has been sent to the governor's desk to be signed into law.

There is some evidence that authorization alone, and not requiring schools to stock naloxone, may not adequately address barriers to making the lifesaving drugs readily available.

California already authorized schools to stock and use the overdose reversal drug, but a new bipartisan bill would amend the previous authorization and require them to keep it in stock. That bill is still pending at the time of writing, and there are concerns about how much the program would cost taxpayers.

A 2021 study published in the journal Public Health Nursing examined Pennsylvania schools' use of naloxone after it became widely available without a prescription in 2015. It found that 55% of public schools stocked the drug, while only 39% of private schools did so. Barriers to school nurses carrying the drug included cost, awareness, lack of community or school support, and negative personal experiences.

Equipping public venues

States, including California and Illinois, have taken steps to require that opioid overdose drugs, also called opioid "antagonists," be available in places where people are likely to use substances.

California business coalitions have supported having naloxone in more establishments as long as the costs are not burdensome. There are also concerns about creating too much demand for overdose reversal drugs, which arose after the legislature proposed another bill that would require all workplaces to stock the drug.

In Illinois, lawmakers amended its liquor laws to require licensed music venues to stock overdose reversal drugs and have staff able to administer them. Lawmakers in Hawaii proposed a bill requiring restaurants to carry naloxone, which is now making its way through the legislative process.

The newly passed laws in Illinois and California also exempt a person from civil or criminal liability if they publicly administer naloxone in "good faith."

Recognizing an opioid overdose

It can be challenging to tell the difference between someone who is under the influence of opioids and someone nearing an overdose or in the midst of one, according to the nonprofit National Harm Reduction Coalition. Someone high on opioids, including fentanyl, might have reduced motor function in their muscles, seem spacey or out of it, slur their speech, scratch their skin frequently, or have small, contracted pupils.

There are, however, several signs someone is in the midst of a dangerous overdose.

- Their body is very limp.

- They are unconscious and do not react to slight shaking.

- They can't talk.

- They have pale or clammy skin or blue or purplish lips.

- Their heartbeat is slow, erratic, or nonexistent.

If the person meets this criteria, and you suspect they might have recently used opioids intentionally or accidentally, you can potentially save their life by acting fast; an overdose can take hours or just minutes to become fatal. The National Harm Reduction Coalition recommends calling 911 immediately, administering naloxone if available, monitoring breathing, and staying with the person until help arrives.

Story editing by Shannon Luders-Manuel. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn. Photo selection by Ania Antecka.