Why administrative health care costs are high and how they can be reduced

This story originally appeared on Soundry Health and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Why administrative health care costs are high and how they can be reduced

Health care services have become increasingly costly, with many Americans seeing insurance premiums rise every year. On top of that, administrative fees—which cover everything from the paper in your doctor's fax machine to the labor it takes to manage complex claims, document clinical information, and request prior authorizations—can often be hidden in medical bills.

Soundry Health examined academic research to see why U.S. administrative health care costs are so high and what could be done to reduce them.

In 2022, the U.S. spent more than 17%—about $4.5 trillion dollars—of its gross domestic product on health care, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of national health expenditure data. In 1970, however, the nation only spent 7%.

Additionally, between 2021 and 2022, total national health expenditures grew by $175 billion, according to the KFF Tracker. Hospital expenditures and retail prescription drugs were the two largest categories that grew, but physician and clinic expenses, medical goods, and, of course, administration costs, also contributed to the growth.

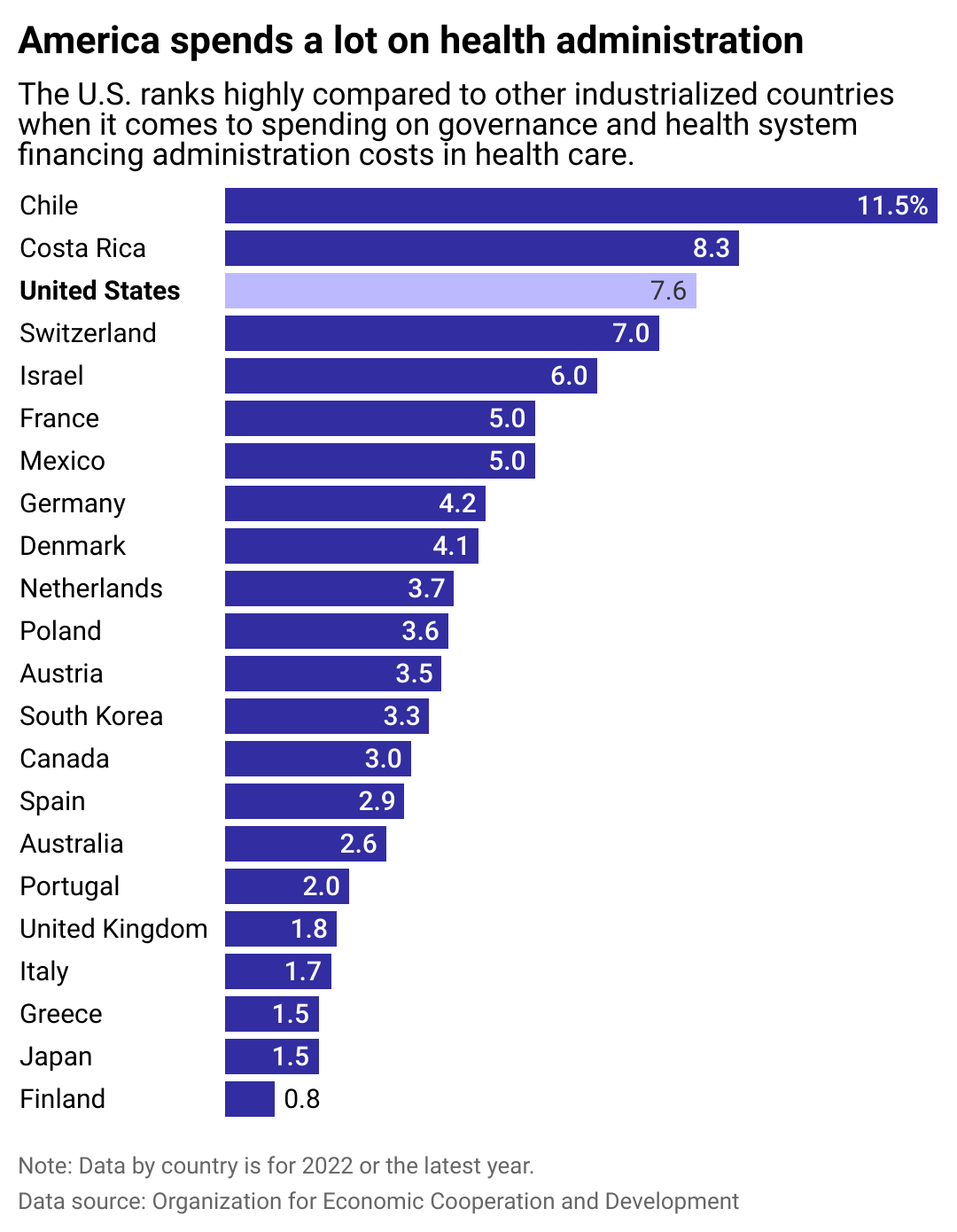

While some researchers vary on what services they define as "administrative," the U.S. spent anywhere from 7% to 34% of its health care dollars on administration as recently as 2022—and no matter how you tally it up, the U.S. spends more on health administration than other similarly wealthy countries such as Canada, Germany, and Japan.

Doctors face 'administrative load,' hampering care

Administrative costs are the "leftover" costs after accounting for clinical activities, explained a Health Affairs research brief on health spending.

Some costs—such as money needed to market an insurance company, the overhead cost of operating a doctor's office, or expenses associated with training hospital staff—are a regular part of doing business, and those expenses aren't likely to go away.

Other, more hidden costs, such as the work it takes providers to locate and log the proper insurer-specific medical codes or the time it takes physicians to seek and obtain prior authorization from an insurance company, can be altered with new nationwide policies or practices.

Many experts suggest a universal health care system as a solution, and in some cases, it has proven to be more cost-effective for the government to set the rates and pay out insurance claims for everyone.

"Reducing U.S. per capita spending for hospital administration to Scottish or Canadian levels would have saved more than $150 billion in 2011," according to one study published in Health Affairs. Scotland and Canada both have universal health care systems.

That same study found administrative costs accounted for more than 25% of U.S. hospital expenditures in 2011, while the same costs made up only about 20% and 15% in the Netherlands and England, respectively.

A separate study, which quantified 2017 spending for administration by both insurers and providers, noted that the gap between Canada and the United States' administrative spending is not only large, but widening. The gap "reflects the inefficiencies of the U.S. private insurance-based, multipayer system. The prices that U.S. medical providers charge incorporate a hidden surcharge to cover their costly administrative burden."

However, universal health care has some drawbacks, and cost savings would depend on how policy is implemented in the states, David Cutler, Harvard professor for applied economics, explained in a policy proposal. For example, one way Canada saves money is by regulating who can obtain medical technology, resulting in fewer MRI machines available to patients—Canada has only one-quarter the number of MRI machines per person compared to the U.S.

Additionally, unless the U.S. implements spending constraints along with universal health care, a remaining concern is that lower administrative costs would cause the volume of services to increase, therefore counteractively causing higher spending. It could also lead back to costly constraints out of necessity, such as the currently used prior authorization requirements.

Alternative ways to reduce administration costs

There are other measures lawmakers and health care leaders can take to greatly reduce administrative burden without overhauling the whole health care system, and Cutler outlines a few.

First, the U.S. can establish a nationwide "clearinghouse" that enforces billing and documentation standards and facilitates payments between providers and insurers.

Something similar exists in banking with the direct deposit system used to distribute paychecks. Although the employer and employee may use different banks, the employer is able to send money directly to the employee's account because almost all banks follow the same rules and standards for transmitting funds, established by the National Automated Clearinghouse Association and overseen by the Federal Reserve.

This lowers banking transfer administration costs from "roughly $300 million annually compared to more than $50 trillion transferred annually," according to Cutler. The health care sector could similarly reduce administrative costs by standardizing documentation and working within a centralized clearinghouse system.

Second, health care leaders and policymakers can simplify prior authorization. Practitioners often have to seek approval from a patient's insurance company before prescribing medicine or scheduling a procedure or test so the insurance companies can make sure costly drugs or services are truly needed, according to Michael Bihari, a pediatrician and former writer for Verywell Health, a health and wellness website.

The American Medical Association calls prior authorization "an administrative nightmare" and notes that physicians and their staff spend an average of 14 hours a week seeking prior authorizations.

This comes at a great administrative cost for insurance companies and providers. The U.S. spent $1,055 per individual on "governance and health system financing administration" in 2020, compared with the average of $193 per person in similarly wealthy countries, according to a report from the Commonwealth Fund. While the report acknowledges higher prices as a driving factor, it also points to excess spending.

Automating the prior authorization system and integrating it into doctors' existing computer systems can speed up the process. The federal government has recently proposed changes to speed up prior authorization, recommending that Medicaid, Medicare Advantage, and insurance plans on the Affordable Care Act marketplace be required to respond to requests within seven days, instead of 14.

Establishing a clearinghouse and streamlining prior authorization would be a challenge that would require the federal government to mandate or incentivize insurance companies, health systems, and providers to share information among themselves and standardize their practices. However, researchers and medical doctors tend to agree that decreasing the administrative load would mean more people can access more affordable care when they need it, according to the AMA, which can be all the more crucial at a time of high inflation.

Health care spending a major focus for US

Americans have seen a slew of health care reform bills over the past decade, and the COVID-19 pandemic brought health spending under more scrutiny. The U.S. did see a bump in health care spending in 2020, but by 2022, it represented a similar share of the GDP as it did before the pandemic, according to the KFF Health System Tracker.

Americans faced price hikes in rent, groceries, and other services immediately following the coronavirus pandemic, and while inflation is beginning to cool, those prices are still elevated compared to 2019.

General inflation outpaced growth in health care spending in 2022, but experts warn that in 2024, employer-based health care coverage will rise at the fastest pace in years. Debbie Ashford, the North America chief actuary for Health Solutions at Aon, said this was because insurance contracts with providers are locked in for several years, so employer-based insurance lags a bit behind the general economy.

So, as medical providers seek to keep up with rising costs of wages and goods, they will demand higher rates from insurance companies in 2024, and Americans will likely see a chain reaction of rising costs.

Story editing by Shanna Kelly and Ashleigh Graf. Copy editing by Tim Bruns.