This story originally appeared on RateGenius and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

The 3,000-year history of toll roads

Paying for passage along one's journey was a common practice even for the gods. Humans have written the ritual into ancient treatises and mythologies. Whether it involves the transportation of souls, livestock, or a road-tripping family of four, the fundamental truth of the road is that travelers must pay their way.

Toll roads are intended to move high volumes of people and goods quickly and efficiently. This is why you'll never see a stop sign or a red light on a toll road. Because of this, they are expensive to build and maintain, so travelers are charged before they can use the road. This money goes towards repairs and improvement, which is why coming across a car-swallowing pothole is a rare sight—unlike on municipal thoroughfares.

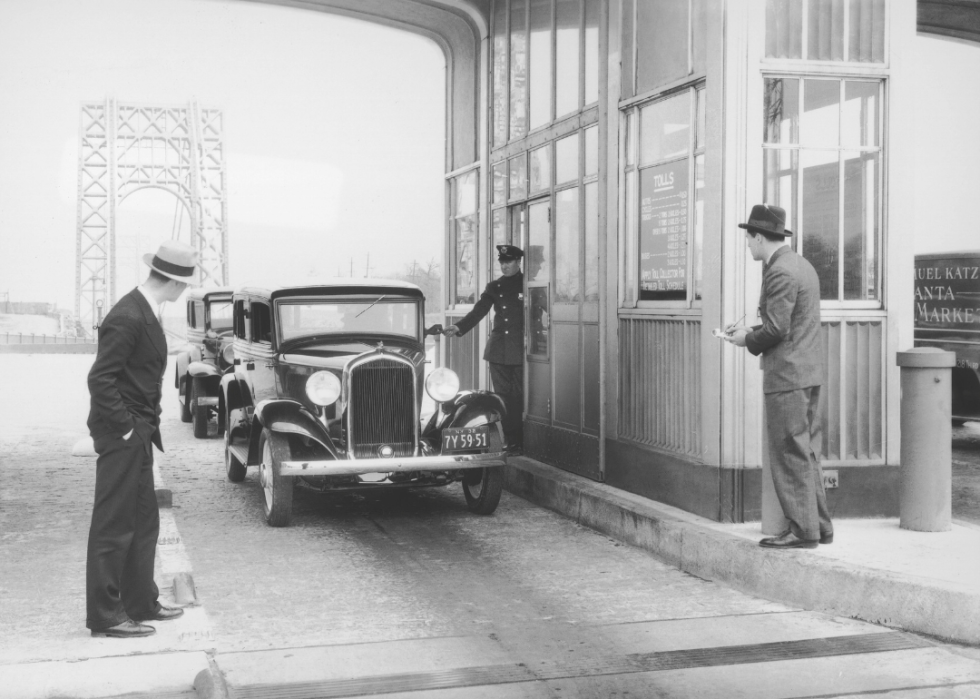

Toll roads have a long history, but the last 30 years alone have brought some of the most rapid and dramatic transformations. In the late 1980s, tolls were manned by human operators; drivers scrambled for exact change as they inched towards the booths, among other drivers fumbling for dollars and cents in a center console. Today, tolls are captured by transponders or license-plate imaging, and the concept of reaching out the window to exchange cash with a tollbooth operator feels nostalgic, almost quaint.

RateGenius compiled this history of U.S. tolling—beginning with its roots abroad and in ancient history—tapping into research from the Federal Highway Administration; the International Bridge, Tunnel and Turnpike Association; and other organizations. Read on to learn more about how culture and policies during the 20th and 21st centuries shaped the evolution of toll roads in the U.S.

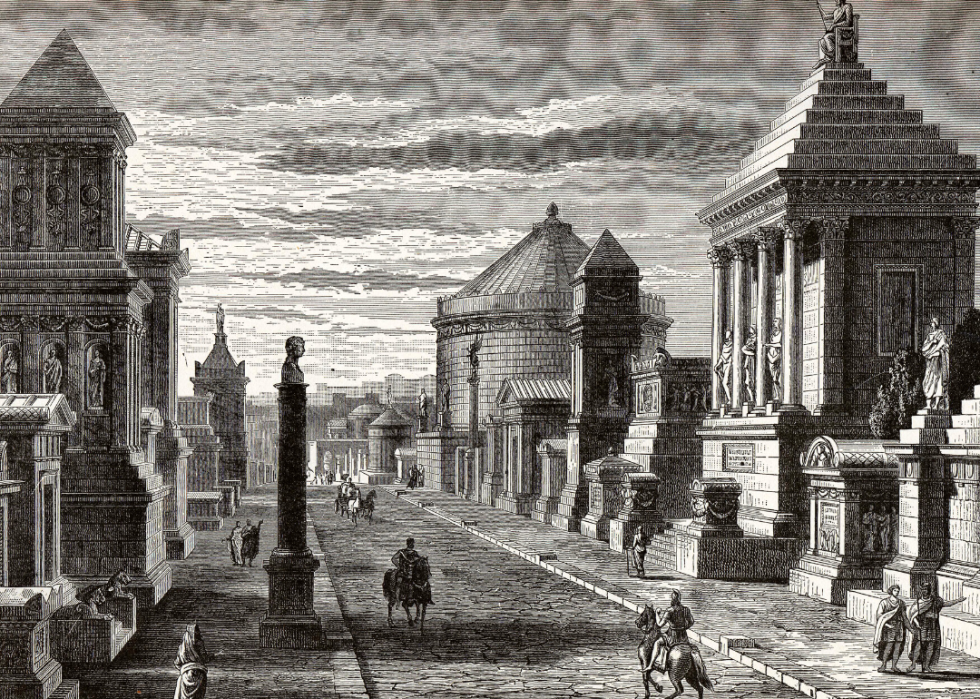

7th to 3rd centuries B.C.: Tolls in mythology and ancient history

In Greek mythology, Charon was a boatman and a toll collector whose job was to ferry souls across the River Styx for Hades, god of the underworld. Payment was a coin placed in the mouth of the dead. Mesopotamian and Egyptian mythologies also contained underworld rivers where souls must be ferried. The oldest reference to tolls in real civilizations is the Arthashastra. Dating back to the third century B.C., the Arthashastra is an ancient Sanskrit treatise on economics, politics, and military strategy and contains an entire chapter devoted to toll payment.

A.D. 500 to 15th century: Medieval tolling

In the Middle Ages, tolls were used to fund bridge construction and maintenance. Travelers were charged for passing over and under bridges. A privileged few who had earned recognition for special services might be granted an exemption from paying toll payments—a reward any commuter would be envious of even today.

17th century: Introduction of turnpikes

Turnpike trusts were among the first official organizations to levy tolls to finance road improvements. This work was formerly done by parishes, which used property taxes and up to six days of labor per year from their residents to finance road work. By the 1830s, the turnpike network in England and Wales included around 1,000 trusts managing 20,000 miles of roadways. Total road spending between 1730 and 1800 increased fourfold as a result of turnpike trust management. Road improvements led to decreased travel time and freight charges.

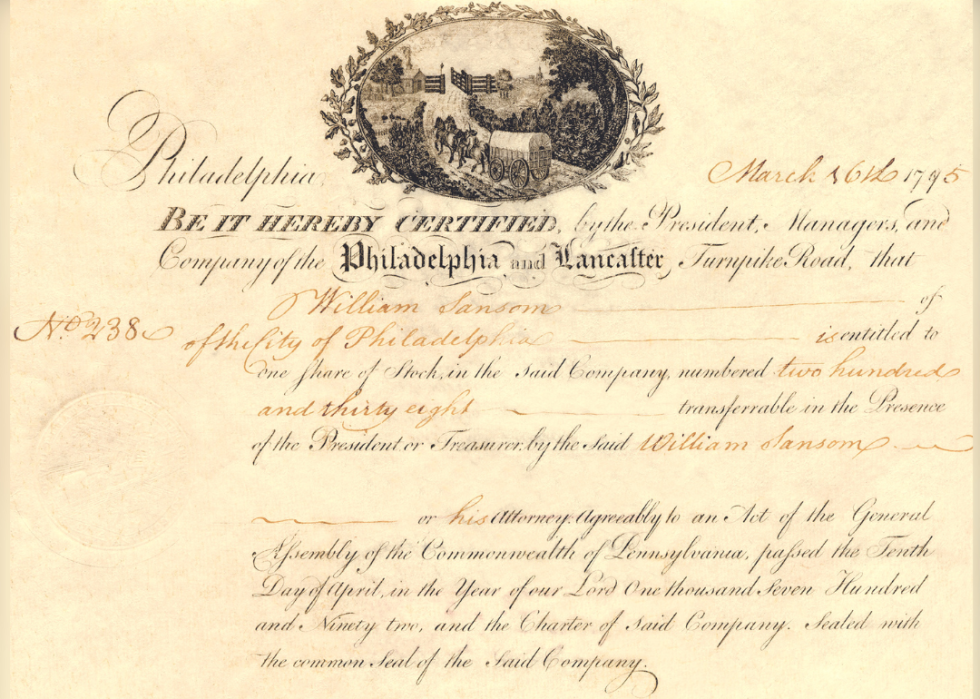

1792: First American turnpike

America's first turnpike, known as the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike in Pennsylvania, was constructed in 1792. Shortly after, dozens of turnpike companies popped up in surrounding states—including Connecticut, New York, and Massachusetts—with longer, better roads expanding outward. In 1806 the federal government agreed to fund the Cumberland Road—stretching from Maryland through Pennsylvania, over the Cumberland Mountains, to the Ohio River.

1916: Federal-Aid Road Act

With the rise of automobiles came an increased demand for better-quality roads than the dirt and loose rock roads that were commonplace. The Federal-Aid Road Act was the first piece of legislation establishing federal funding for the construction of rural post roads—or any public road by which mail was delivered—with the condition that they would be toll-free. While that provision still exists, there are exceptions to the blanket ban on tolls. New construction of roads, bridges, and tunnels may be tolled, and preexisting infrastructure may be tolled if they are reconstructed or replaced.

1921: Federal Highway Act of 1921

With more than half of all families owning a vehicle by the 1920s, the Federal Highway Act of 1921 spurred more construction of roads, bridges, and tunnels. The act provided some financial assistance to states, but many of these projects were funded through tolls.

1945-1955: Many state turnpikes built

World War II significantly increased reliance on American roadways, as soldiers returning from war were met with a GI Bill that allowed them to purchase homes in newly constructed suburbs winding out away from cities and employment. The commute, the Sunday drive, and the distinctly American tradition of drive-in restaurants and movies were all born of this time.

Car culture meant more roads and more road maintenance. State turnpikes were constructed en masse throughout the late '40s and early '50s, with funds raised at tolls ostensibly going to road repair—although a 2017 report from American Transportation Research Institute (the nonprofit arm of American Trucking Associations) found that tolls were the least effective means of funding national highways.

1956: Federal-Aid Highway Act

Also known as the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act, this legislation provided federal funding for the creation of the interstate highway system. A federal Highway Trust Fund—generated primarily by taxes on fuel, as well as buses, trucks, and tires—would cover 90% of highway construction costs, and states were required to pay the remaining 10%. Funding construction through tax preserved the toll ban established in the Federal-Aid Road Act of 1916.

1980s: Electronic tolling systems introduced

Electronic tolling systems are relatively new on the long timeline of toll collection. The first electronic tollbooth in the world, located in Norway, wasn't installed until 1987. Throughout the 1980s, electronic tolling technology was exploratory, pursued primarily by universities and in-house U.S. Department of Transportation researchers.

An engineer named Mario Cardullo was circling the million-dollar idea in the 1970s when he patented a transponder that could transmit information, but it expired in 1990. By the next year, the Oklahoma Turnpike Authority's Pikepass became the first electronic toll collection system in the United States.

1991: The Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991

This act had three primary goals, including intermodalism, flexibility, and efficiency. This legislation permitted the tolling of non-interstate federal-aid highways. Additionally, existing roads and bridges—otherwise banned from tolling—would be able to implement fees only after reconstruction. This provision connected and incentivized road improvements as a means to obtaining tolling revenue.

1990s: Private sector tolling emerges

Public-private partnerships, or P3s, formed to develop, construct, and manage highways is not exactly a new idea—the 1792 Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike was a P3. But by the 1990s, it was recognized by private industry that highway tolling was pretty big business. In 1998, the passage of the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21) pumped billions of dollars into state coffers for road projects, and with it states began to delve further into building toll roads.

The manner by which private enterprise operates on a tollway is what's known as "concession." Here, a private company concessionaire can invest its own money to construct a toll road project. Or, in the case of an existing toll road, it can use a combination of equity and debt to pay its public partner for the right to operate the tollway for a specified period of time. Companies will usually collect toll revenue either by taking periodic payments based on the tollway's rate of revenue or by taking a "shadow toll," which is a pre-set percentage taken from each toll collected.

The U.S. PIRG Education Fund determined that from 1994 to 2006, P3s invested $21 billion in 43 toll facilities across the country.

2000s: New focus on HOV tolling and congestion pricing

To reduce areas where traffic is the worst, the 21st century brought with it calls for "congestion pricing" and high-occupancy vehicle tolling.

In a congestion pricing model, toll rates are adjusted according to peak use times like rush hour in the hopes of pushing drivers to seek alternative modes of transportation such as public buses or subways. New York City is expected to roll out congestion pricing in Manhattan sometime in 2023.

High-occupancy tolling entails allowing passage free of charge to HOVs and other exempt vehicles while charging a variable fee to other vehicles based on demand.

Both of these mechanisms are part of the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users, which earmarked more than $200 billion for American transportation infrastructure improvements, environmental protection, and to support economic growth.

2008: Taxes and fees fail to fund transportation

In 2008, the Highway Trust Fund ran out of money, and Congress completed an $8 billion bailout. The Great Recession led to higher fuel costs, less gasoline consumed, and as a result, less fuel tax being banked. Moreover, the fed refused to raise the gas tax, despite the recession (as of 2022, it has not been raised since 1993). The proposed solution was to expand tolling to cover the deficit, but tolls—even electronic ones—were found to be inefficient and expensive, eating into overall revenue by 10%. And that doesn't even factor in the actual tolling infrastructure.

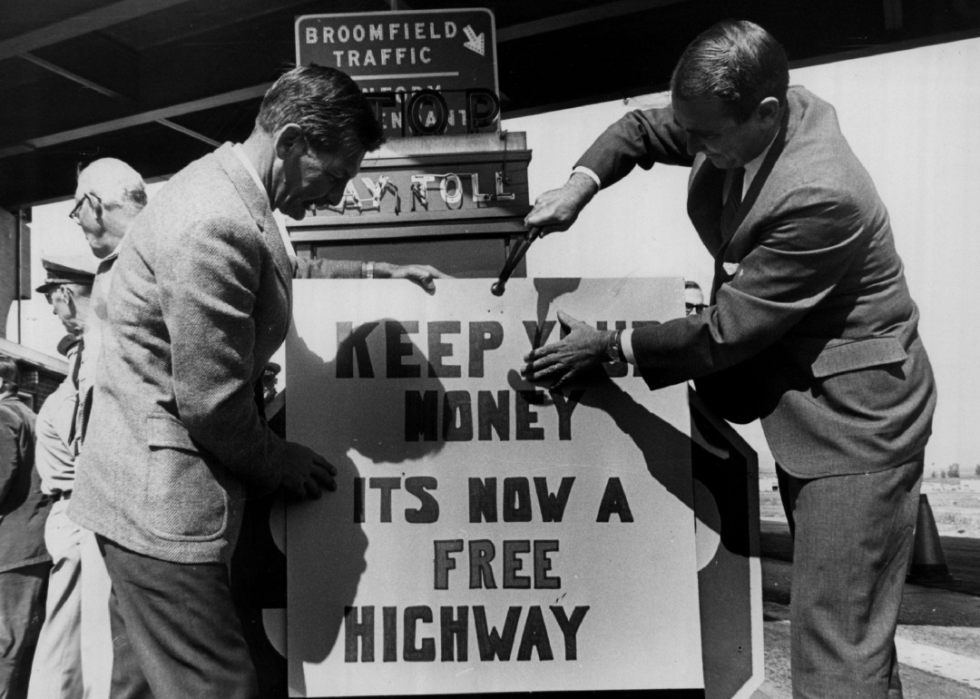

2010s: Cashless tolling

Completely cashless tolling first began as an experiment in the Denver area around 2009, though electronic tolling systems had been in place as early as 1989 on the Dallas North Tollway in conjunction with traditional cash booths. Over the last decade, electronic tolling gained traction as a safer, more efficient way to collect tolls.

Cashless tolling keeps vehicles moving steadily with little to no wait times and can even help mitigate congestion by allowing operators to raise and lower prices. COVID-19 pushed many road systems to adopt a cashless model to eliminate physical transactions and potential spread of the disease. In July 2022, the George Washington Bridge became the latest cashless crossing.

2020 and beyond: COVID-19 diminishes toll road travel

COVID-19 restrictions, the work-from-home movement, and permanently altered commuter habits have resulted in less road traffic and fewer tolls being paid over the last two years. Some markets, like the Maryland Transportation Authority, predict losses in the hundreds of millions due to these factors. The MTA announced a $422 million reduction in toll revenue through 2026 partly due to the pandemic. Although restrictions have been lifted and more people are returning to pre-pandemic travel, industry experts anticipate the industry will lose more than $9 billion nationwide.