From Kodak cameras to the internet: The evolution of American privacy law

This story originally appeared on Zapproved and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

From Kodak cameras to the internet: The evolution of American privacy law

Privacy is both a moving target and a living thing, requiring constant updates to the American body of law in order to keep up.

From the end of the American Revolution to the present, Zapproved compiled a timeline of federal privacy law in the United States. These landmark pieces of writing or legislation illustrate the extent to which privacy—and how it’s defined and regulated—has played a role in the American way of life since the time of the country’s Founding Fathers.

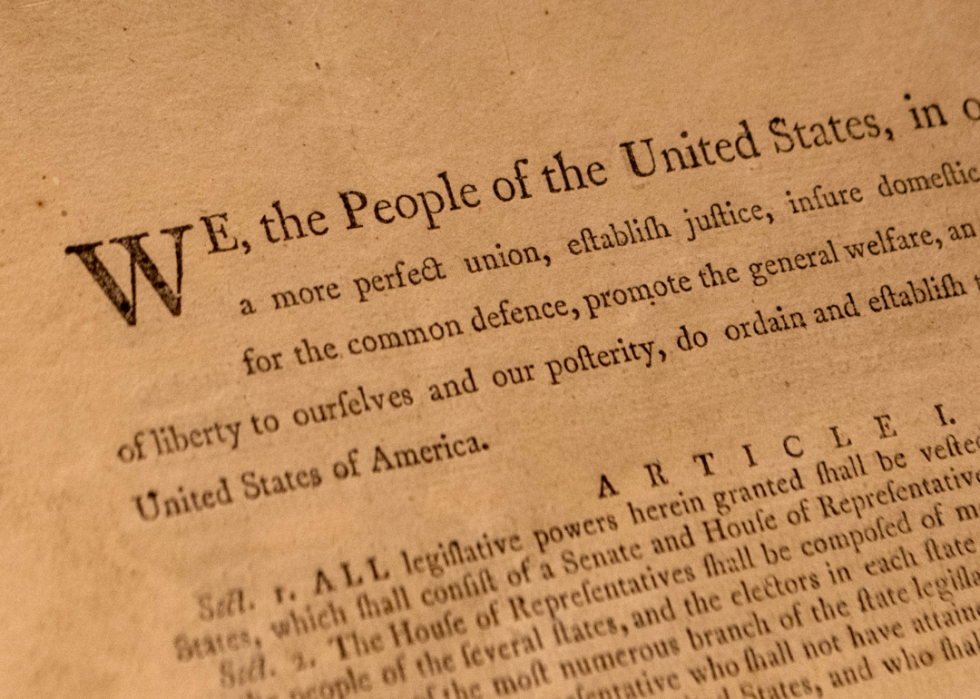

Following the writing of the U.S. Constitution in 1787 (ratified in 1788 and operational since 1789), colonists ratified the Bill of Rights in December of 1791. These constitutional amendments represented essential liberties that colonists claimed at the time, including the First Amendment protecting freedom of speech and the Second Amendment affirming all citizens’ rights to keep and bear arms.

The little-publicized Third Amendment, which prohibited the federal government from requiring households, private businesses, or local governments to house soldiers, may seem abstract today. But that amendment ultimately established a level of protection for an American citizen’s right to ownership and use of property without government interference.

Keep reading to learn more about how American culture, invention, and adoption of technology helped to shape how we perceive and legislate privacy in our own homes, in public, and online.

1789: The US Constitution's Fourth Amendment

The fourth entry in the Bill of Rights offers citizens protection from “unreasonable searches and seizures... and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

This is often shortened to “no unreasonable search,” safeguarding the public from government searches of property or person without due cause. In most cases, that cause requires a warrant, except in the case of emergencies or when “probable cause” is up to the judgment of police.

1888: ‘Kodak No. 1’ camera courts debate over privacy rights

When Kodak introduced the first popular amateur camera, the company opened a floodgate of concerns about privacy as it became viable for virtually anyone to spy on or document the actions of their family, friends, and neighbors—not to mention celebrities and politicians. By the time Kodak’s founder, George Eastman, released the mass-produced Kodak Brownie camera in 1900 for $1 a pop, photography had officially gone mainstream.

While photography is protected by the First Amendment, there are many documented cases even today of photographers being compelled to defend their use of photography in public spaces. And although public photographs of people are also protected, by 1890 a person’s right to their own likeness was called into question.

1890: Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis write "The Right to Privacy"

Warren and Brandeis’ influential 1890 article “The Right to Privacy,” published in the Harvard Law Review, picks up many of the thorny issues raised by the first availability of Kodak’s amateur camera.

“The Right to Privacy” was widely considered among the most influential law review articles written and has been credited with pushing more than a dozen state courts to recognize similar laws to individuals’ rights to privacy. Among those bills was New York’s adoption of sections 50 and 51 in its Civil Rights Law, affirming individuals’ rights to the use of their own likeness.

Suggestions outlined by Warren and Brandeis further paved the way for other state laws, such as rendering the recording of private conversations without both parties’ consent illegal. Other issues, like whether people running for public office should still have privacy in their personal dealings and actions, continue being debated today.

1917: The Espionage Act

It’s resoundingly commonplace for the U.S. federal government to limit civilian rights during wartime, from President Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus during the Civil War or the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

The Espionage Act of 1917 pulls a page from the same playbook. In it, the government outlines that certain dangerous ideas are “enemies” of the United States and can be punished by law. These ideas included certain actions, like whistleblowing, considered harmful at the time to the United States armed forces.

Edward Snowden is one of the most high-profile people to have been charged with crimes against the state under this act.

1960: William L. Prosser outlines the privacy torts

In 1890, Warren and Brandeis examined the existing body of law in order to discuss privacy as a legal ideal. By 1960, William Prosser, the dean of the University of California–Berkeley’s law school, nailed down his choice of four torts concerning privacy.

A tort is a cause allowing people to sue in civil court for financial damages. Prosser’s torts concern intrusion into private life, disclosure of embarrassing facts, misleading publicity, and appropriation of someone’s likeness. In the modern age, critics of Prosser’s privacy torts say the list, while influential, does not adequately protect people from intrusions such as data gathering or identity theft.

1965: Griswold v. Connecticut

Until 1965, Comstock Laws—which aimed to prevent the sale of licentious materials like pornography—also ensured the illegality of selling contraceptives.

Estelle Griswold, the head of Connecticut’s branch of Planned Parenthood at the time, went before the Supreme Court to represent the movement to legalize contraceptives. The Court ruled to legalize the sale of contraceptives, finding the Constitution protects a married couple’s right to marital privacy and protection from state restrictions on contraception.

1967: Katz v. United States

Charles Katz was a wildly successful bookie in Los Angeles who calculated the fluctuating odds that one team would win over the other—known as “handicapping.” The FBI, suspicious Katz was illegally communicating gambling information to clients in other states, discovered he was using a payphone to relay information to clients.

Because the payphone was technically public, the FBI was able to use eavesdropping technology to catch Katz red-handed and convict him on eight counts for illegally transmitting wagering information to Boston and Miami.

Katz and his attorneys appealed the decision all the way up, with the Supreme Court ultimately ruling that people have the right to Fourth Amendment protections and a reasonable expectation of privacy, even in public places. This ruling has been particularly influential in the internet age.

1974: The Federal Privacy Act and Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act

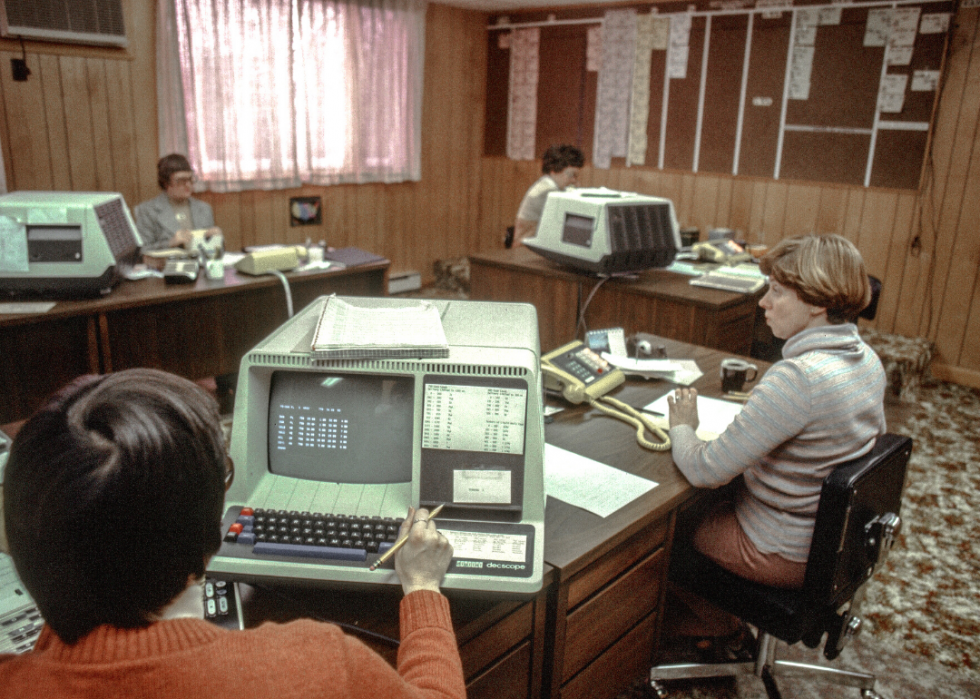

The Privacy Act of 1974 deals with the way federal agencies handle the data of Americans. It came about in response to public concerns about how the creation and use of computerized databases, first introduced in the ’60s, could affect individual privacy rights.

The act establishes that agencies must secure records, keeping them safe unless the person in the record explicitly signs off on any additional use. People also have the right to see and amend what their federal agency records may say about them.

There are a number of exemptions given to the Privacy Act of 1974, including for simple statistical purposes like the U.S. Census as well as more salient law enforcement reasons. There are also de facto exemptions because of the number of records that are held outside of strictly “agencies,” like those of U.S. courts.

1984-1998: Privacy laws on cable, telecommunications, and video are signed

By the 1980s, technology had again begun to accelerate leagues ahead of the existing body of privacy law. Consumers began to use home computers with rudimentary modem technology. People at public universities and government facilities were connected in the earliest form of what later became the internet. These emerging networks warranted a new kind of privacy protection.

The Cable Communications Policy Act of 1984, The Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986, and the Video Privacy Protection Act of 1988, among others like them, sought to protect people from the computer equivalent of wiretaps, making it illegal to “listen in” on regular electronic communications.

1996: Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act is better known by its abbreviation, HIPAA. This influential and wide-reaching law prevents patient information from being shared without patient permission.

In it, HIPAA states that only patients and their authorized representatives are able to access the patient’s health records or information. The act has been in effect for most of the era of mainstream internet use. A key application of HIPAA came up during the coronavirus pandemic in regard to health care providers being required to use secure channels to message or videochat with patients.

1998: Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act

Keen-eyed observers noticed a Twitter crackdown several years ago when a variety of accounts disappeared because of their listed birthdays. These accounts fell afoul of the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act, which makes it very legally complex for companies like Twitter to allow users under the age of 13. Of course, on Twitter, this also affected silly pet accounts and organization accounts that listed their founding dates.

It’s not actually illegal for users under 13 to sign up for accounts on these sites. The law outlines exactly how sites could communicate with parents or guardians in order to obtain the right consent. But to do so on a wide scale seems to have intimidated most social networks, for example, which opted to simply ban users under age 13 altogether.

1999: Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act

The Gramm–Leach–Billey Act (GLB) accounted for a specific way banks wanted to be able to consolidate different functions, inspired by a real-life merger between a bank and an insurance company. Whether that is or isn’t a good idea is in the eye of the beholder, but the act also goes into detail about some aspects of banking privacy. If you receive an annual privacy notice from your bank, from PayPal, or from any other financial institution, that’s because of the GLB. Banks must disclose how they gather information as well as how that information is to be used. They must also detail how they protect the information.

2014: USA Freedom Act

Hot on the tails of the expiring USA Patriot Act, the USA Freedom Act introduced certain protections for Americans while holding up or introducing new invasions of privacy by the government. The law is also a response to the Edward Snowden leaks describing extensive government monitoring of communications.

The USA Freedom Act is: “An Act to reform the authorities of the Federal Government to require the production of certain business records, conduct electronic surveillance, use pen registers and trap and trace devices, and use other forms of information gathering for foreign intelligence, counterterrorism, and criminal purposes, and for other purposes.”

The law gently juggles what the government is allowed to demand, striking a balance between the post-9/11 Patriot Act and the post-Snowden interest in restoring privacy.