How school cafeteria meals have changed

A piece of President Joe Biden's recently released American Families Plan aims to provide school lunches throughout the summer to some 29 million school-aged children. If passed, the proposal would greatly expand the current school lunch program and ensure that millions of food-insecure children are guaranteed at least one meal each day. Throughout the pandemic, a short-term version of the program has been in place, but this new proposal would make it permanent.

The idea of feeding children who might otherwise go without is at the heart of the public school lunch program. In their earliest days, these programs were run by charities and welfare organizations that wanted to prove that good nutrition was foundational to success in school and in life. While the nutritional aspect of cafeteria meals may have been lost over the last century or so, the belief that a full stomach is an important part of a person's success has remained intact.

Using government and news reports, Stacker has traced the history of cafeteria meals from their inception to the present day, with data from news and government reports. Read on to see how various legal acts, food trends, and budget cuts have changed what kids are getting on their trays.

1894: First school lunch program appears

Ellen Swallow Richards, a nutrition and home economics pioneer, began the first-ever school lunch program at Boston Latin School, the oldest public school in the country. Under the umbrella of her company, The New England Kitchen, which was designed to provide the poor and immigrant communities with nutritious and affordable meals, Richards began serving hot lunch at the school daily. Meals were free to students, included items like fish chowder and bread with butter, and cost about 10 cents to prepare.

1900: Boston and Philadelphia lead the way

Following the success of Richards’ experiment, the first school lunch programs began appearing in Boston and Philadelphia by the early 1900s. By no means city-wide, these programs were run by charity organizations who would prepare the food in a central kitchen, then deliver it to participating schools. By 1913, it is estimated that there were 40 similar programs in place around the country, serving students for just 1 cent a meal. Meals were composed of things like pea soup, rice pudding, and lentils.

1920s: “The Americanization agenda”

According to Harvey Levenstein, author of “Revolution at the Table,” one of the unspoken early goals of public school lunches was to Americanize the tastes of immigrant youth. He writes: “[the immigrant children] were learning an important lesson: it was the food in their homes, not on the steam tables, which was out of the mainstream, and that to enter that stream they would ultimately have to learn to appreciate its food."

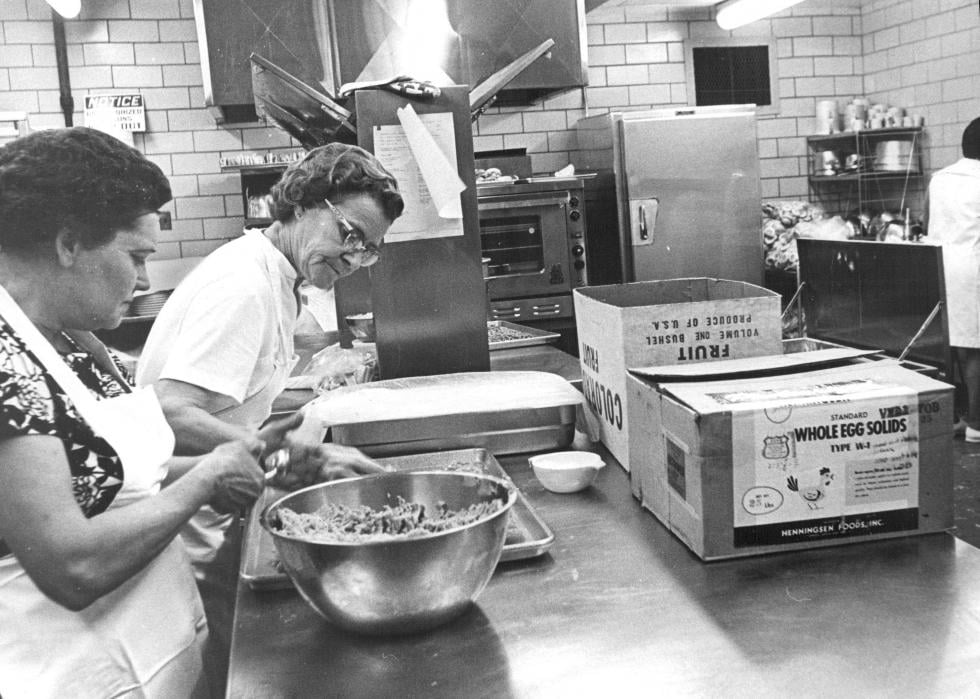

1930s: School lunch and the New Deal

During the worst years of the Great Depression, food was scarce and work even scarcer. As a part of his New Deal, President Roosevelt bought up surplus food from farmers, then hired thousands of out-of-work women to cook and serve the food to hungry public school students. The program was so successful that by 1941 every state (plus Washington D.C.) had a lunch program in place. A typical school lunch at the time included items like veggie soup, peanut butter sandwiches, and the occasional piece of fresh fruit.

1940: WWII ups the ante

In the 1940s, as the U.S. escaped the Great Depression and entered into WWII, it began to understand just how devastating those lean years had been. As the country called up its young men to fight, it realized that up to one-third of them were unfit for service due to malnutrition (compare this to today, when 20% of Americans are unfit for service due to obesity). This was the first time that the welfare of the country's kids was identified as an issue of national security. Entrees like creamed chipped beef, cornmeal pudding, and a pork dish called scrapple were all popular offerings.

1946: The National School Lunch Act signed

As a result of these realizations, President Truman signed the National School Lunch Act in 1946. Through federal subsidies, the act provides low or no-cost school lunches to children who need them.

1950s: Nutritional quality goes down

In the 1950s, with the rise of pre-packaged convenience foods and the government’s emphasis on lowering food costs overall, the nutritional quality of school lunches plummeted. Although schools were serving calorically dense meals, they often offered little in the way of healthy veggies, fresh fruits, or lean proteins, instead offering things like cheese meatloaf and sausage shortcake. The lack of nutrition was one of the driving factors behind the Child Nutrition Act of 1966, which gave control over what schools could offer at mealtime to the Department of Agriculture.

1962: National School Lunch Week established

In 1962 President John F. Kennedy created National School Lunch Week to advocate for healthy and nutritious school lunches for children. The program’s purpose is two-fold—to encourage children and teenagers to make healthier choices and to remind those in charge why continual funding for the National School Lunch program is so important.

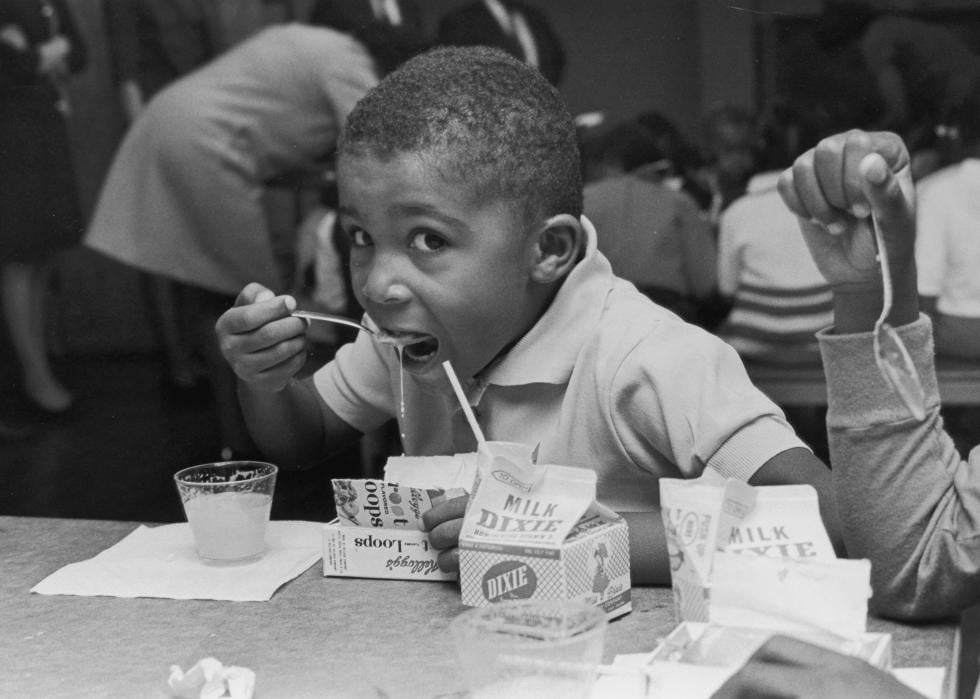

1966: School breakfast program begins

Another aspect of the Child Nutrition Act that President Johnson signed in 1966 was the establishment of a school breakfast program. Public schools and daycare centers across the country began offering free or low-cost breakfasts to students in need before the school day began. Typical menu items include fresh fruit, assorted pastries, yogurt, and cereal.

1966: Special Milk program first offered

A third tenet of the Child Nutrition Act was the Special Milk Program, which provided students with free milk with every meal. In the '60s, the beverage typically accompanied foods like meatloaf and mashed potatoes, peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, and fish sticks, though options like enchiladas and chili con carne were making their way onto many menus.

1968: Summer food program begins

After realizing that food insecurity was not an issue that went away when the school year ended, the Summer Food Service Program began in 1968. Initially just a three-year program, the service provided meals to children who may not otherwise have them through the public school system. The programs often go hand-in-hand with a school’s summer program, which serves as free childcare throughout the warmer months.

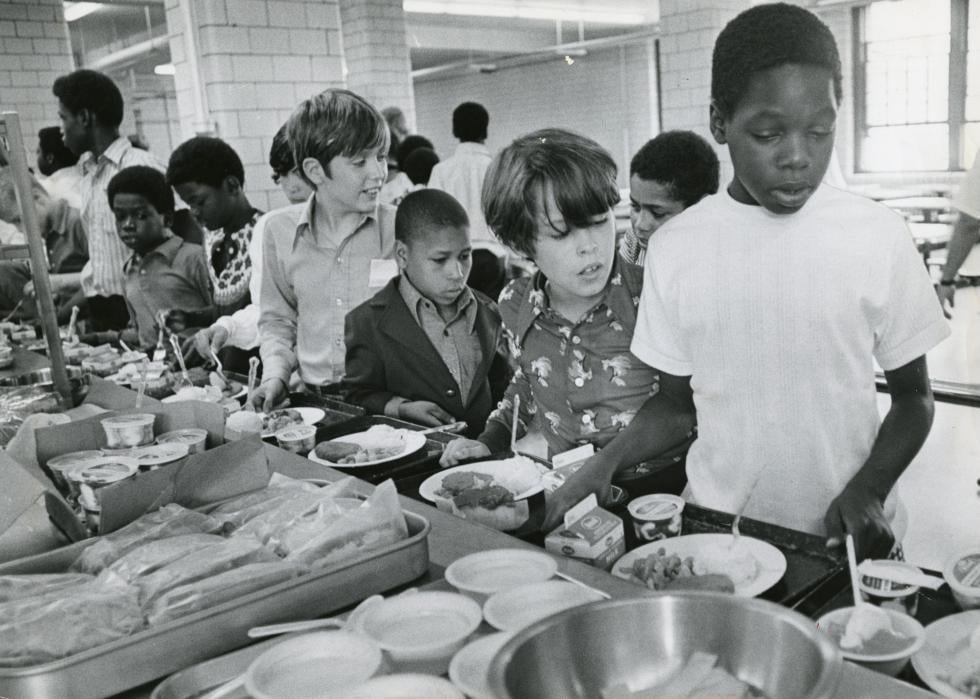

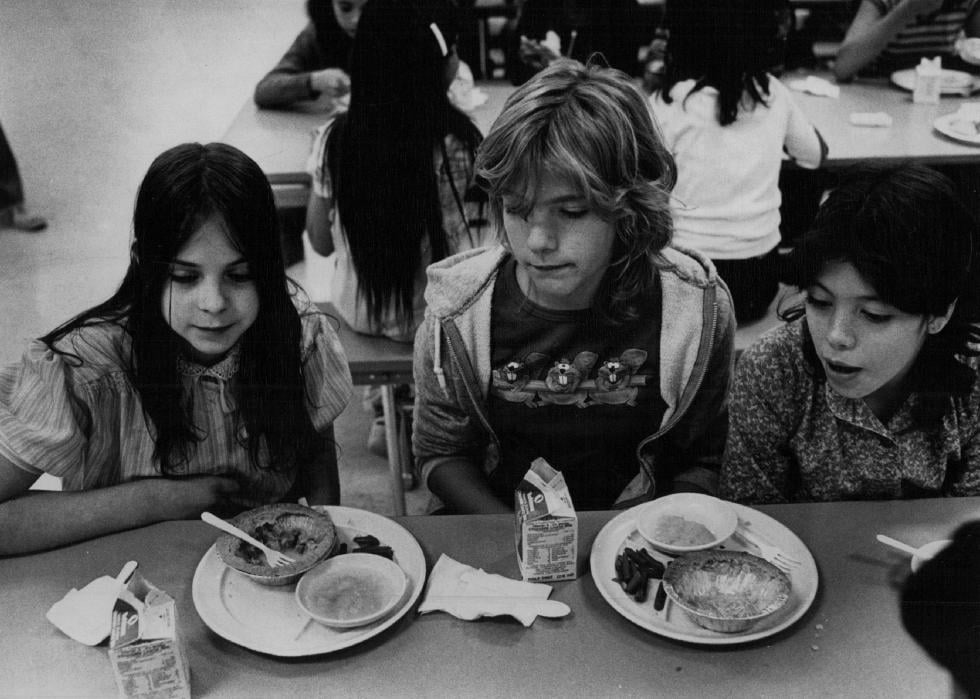

1977: Nutritional value called into question

In the 1970s, the nutritional quality of school lunches was called into question again when a government report found that the meals “fell far short of providing minimum nutritional standards,” were high in fat and low in iron, and could be linked to growing rates of obesity. These findings came as schools began serving dishes like hamburgers, chili dogs, fried chicken, and fruit gelatin.

1981: Ketchup is a vegetable

In the early 1980s, the Reagan administration cut federal funding for lunch programs around the country, which resulted in shrinking portions and reduced eligibility for free and low-cost lunch. The cuts also resulted in ketchup being accepted as a vegetable, demonstrating just how far standards had fallen since the first programs were offered back in the late 1800s.

1980s: School lunches become a privatized business

As a result of the budget cutbacks, many districts outsourced their school lunch program to private companies in the 1980s. An effort to save on cost, this meant that nutritional standards were further skimped on and overall quality went down. Frozen and processed fare began to rule the school, with offerings like chicken nuggets, pizza, and chocolate pudding landing on almost every tray.

1995: The Department of Defense is placed on vegetable duty

By 1995 the nutrition situation had gotten so dire that the Department of Defense was tasked with providing freshly grown fruits and veggies to American public schools. An extension of an existing program that also supplied Army bases, this move went a long way in helping offset some of the consequences of other school lunch trends.

2000s: Fast food vendors amp up their lunchroom presence

The trend in question? The increased presence of fast food vendors in public school lunchrooms. By 2005 an estimated 50% of cafeterias offered meals from restaurants like McDonald’s, Chick-fil-A, and Little Caesar’s, all of which met (low) federal government standards and helped with funding.

2010: The Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act passes

The Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act from the Obama era gives free lunch and breakfast to every kid in school where 40% or more of the student body is food-insecure. This helps to eliminate food shaming, cuts down on administrative work, and ensures that all children, even those who might not technically be food-insecure but don’t always have access to high-quality meals, are fed.

2014: Smart Snacks in School standards implemented

Another recent set of regulations, the Smart Snacks in School standards created guidance around the nutritional values of foods and beverages that are sold in schools outside of the federal meal program. These standards place limits on the amount of fat, sugar, sodium, and calories that are acceptable, with the object of lowering obesity rates.

2018: Trump rolls back nutrition standards

In the middle of his single term in office, President Trump quietly rolled back Obama-era regulations that limited sodium content and mandated the inclusion of whole grains in school lunch entrees. In 2020, the rollback was reversed, but for a two-year span, students were back to eating higher-calorie, lower-nutrient options for breakfast and lunch each day.

2020: COVID-19 necessitates curbside grab-and-go

When COVID-19 upended life and the school year at the beginning of 2020, many schools began offering their students meals through curbside pickup. This policy has extended through the 2020-2021 school year, and many wonder if it's here to stay.