50 facts and figures about D-Day

Five years into World War II, the Allies were squeezing the Nazis from two sides. In Western Europe, Allied forces had managed to slow Adolf Hitler's ruthless expansion across the continent. Meanwhile, to the East, the Russians had successfully locked German forces into a brutal war of attrition. Nazi Germany, however, was still firmly secure in its continental fortress. And scores of occupied nations suffered as a result.

Then came D-Day.

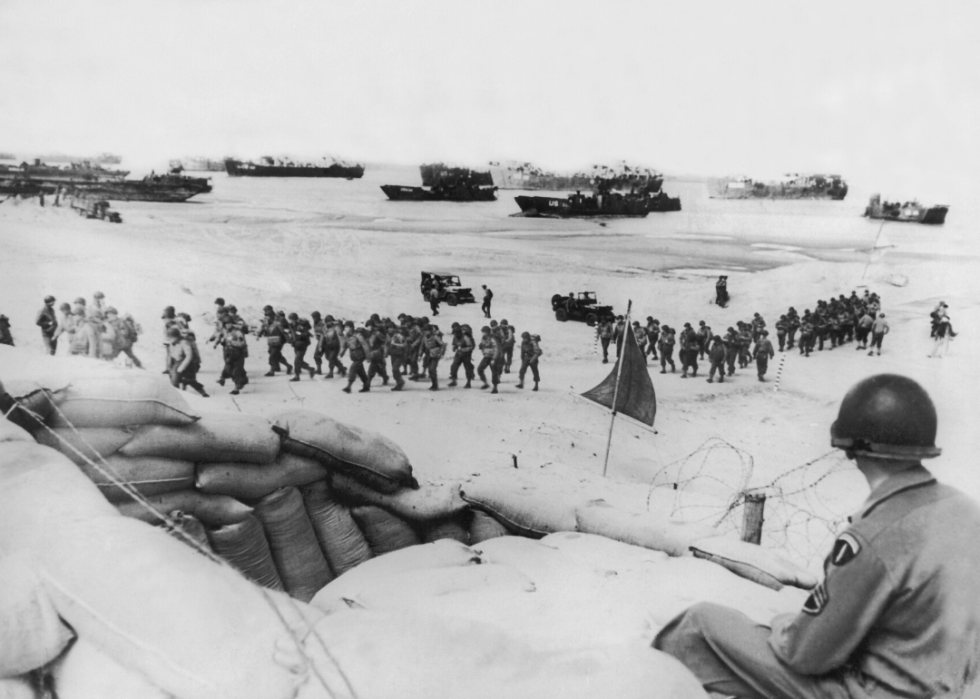

On June 6, 1944, Allied planes, ships, vehicles, supplies, and men from the United Kingdom, United States, France, and Canada stormed the coast of occupied France's Normandy region in numbers so staggering they're difficult to comprehend. The largest amphibious operation in the history of warfare, the Normandy landings—better known as D-Day—were years in the making.

Supported by meticulous planning, cunning deception, and pitch-black humor, D-Day marked a gargantuan effort to dislodge and dismantle one of the most effective war machines ever assembled. On that gloomy spring day in 1944, Normandy became the final resting place for thousands of fallen soldiers–a costly first step in a months-long campaign that culminated in the liberation of Paris, and ultimately, the fall of Nazi Germany and the end of the Second World War in Europe.

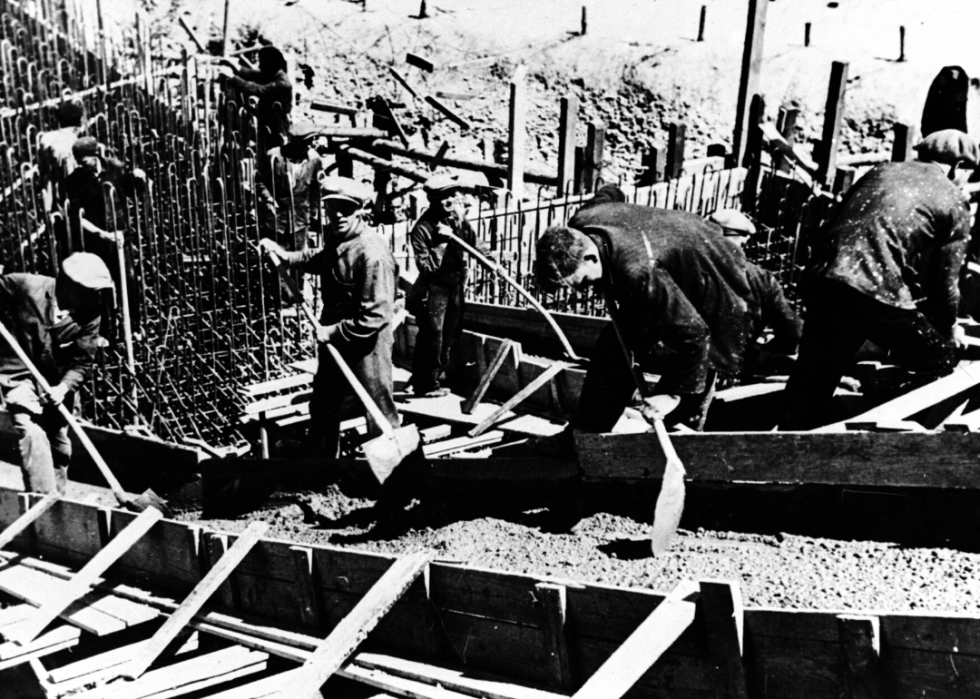

The German defenders, however, did everything they could to prevent that from happening. The Nazis used their plundered wealth—not to mention armies of enslaved laborers—to construct defensive fortifications that remain among the largest, most robust military entrenchments ever built. Those fortifications were manned by well-armed and battle-hardened German troops who fought to defend the real estate they were charged with holding.

The result was one of the most significant military events in human history. The 81st anniversary of that battle takes place this month, on June 6, 2025. Festivals and commemorations to mark D-Day's global significance include everything from veteran pilgrimages to reenacted parachute drops to powerful memorial art installations, like the "Standing with Giants" installation at the British Normandy Memorial.

To recognize this landmark event, Stacker compiled a list of 50 facts and figures that defined the historic landings. Sources include the D-Day Center, the Department of Defense, and the White House, as well as media reports, historical accounts, and information from memorial sites and museums. Keep reading to learn more about one of the most consequential days in military history.

It was the largest amphibious assault in history

The mythical Greek siege of ancient Troy is probably the most famous and romanticized amphibious assault in history. The Normandy invasion, however, was very real. To date, it is the most significant waterborne attack ever to take place on any shoreline anywhere at any time.

The 'D' in D-Day is redundant

The "D" in D-Day stands for "Day," the traditional military protocol used to indicate the occurrence of a major operation. The day before D-Day, June 5, was D-1. The day after, June 7, was D+1.

Secrecy and deception were key

Dubbed "the century's best-kept secret" by the Saturday Evening Post, for years, the Allies executed a series of elaborate ruses known collectively as Operation Fortitude, designed to hide Allied intentions from the enemy. They spread misinformation through false news reports, planted intelligence, and created false radio broadcasts designed to be intercepted by the Axis powers. They also created make-believe tanks composed of wood and rubber, fake troop encampments, and launched fleets of inflatable dummy warships.

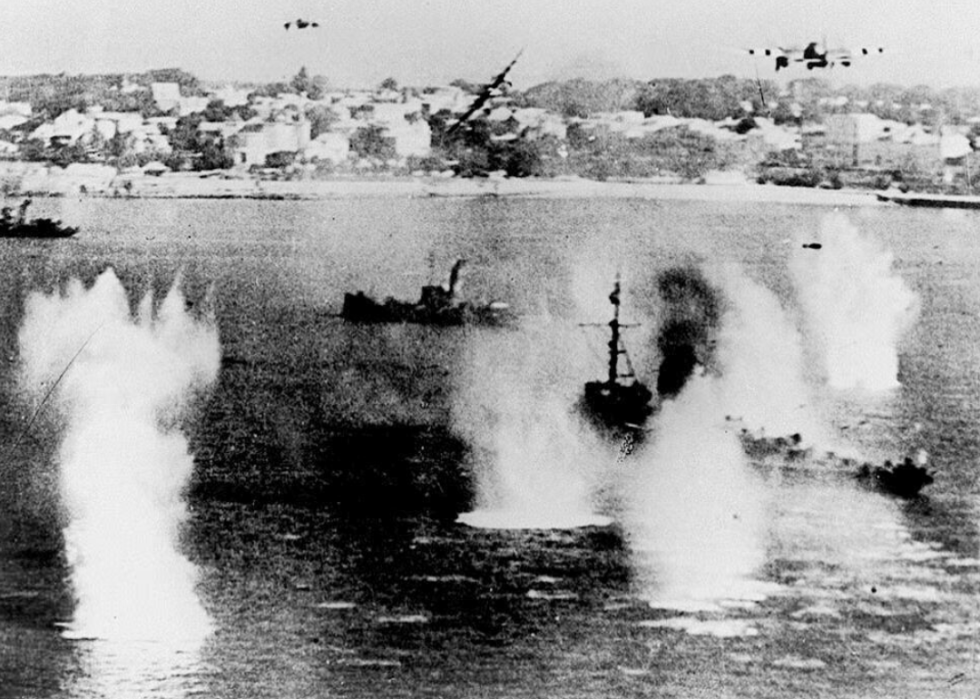

The practice run turned deadly

Exercise Tiger, a D-Day dress rehearsal, proved as fatal as Omaha Beach. Around 700 Allied sailors and soldiers died in a training exercise at a friendly British beach. Speedy German attack vessels called E-boats became aware of the rehearsal and attacked the Allied flotilla, sinking several ships with torpedoes. Some survivors who went on to storm the beaches of Normandy later recalled that the Exercise Tiger fiasco was more terrifying than D-Day itself.

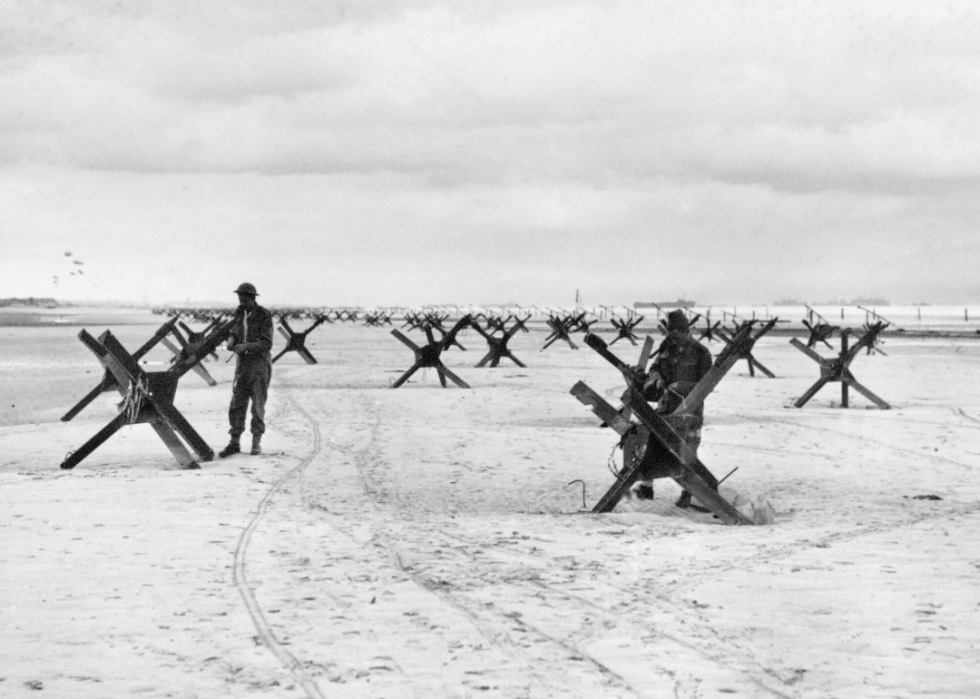

German defenses were the war's biggest construction project

The Germans had been anticipating an Allied invasion by sea since at least 1942. To prepare, they began construction that year of the Atlantic Wall, an enormous defensive fortification stretching from the west coast of Norway, down through Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France, to the border of Spain. Bristling with weapons, bunkers, and early warning systems, the Atlantic Wall, completed in 1944, is remembered as one of the greatest feats of military engineering in history.

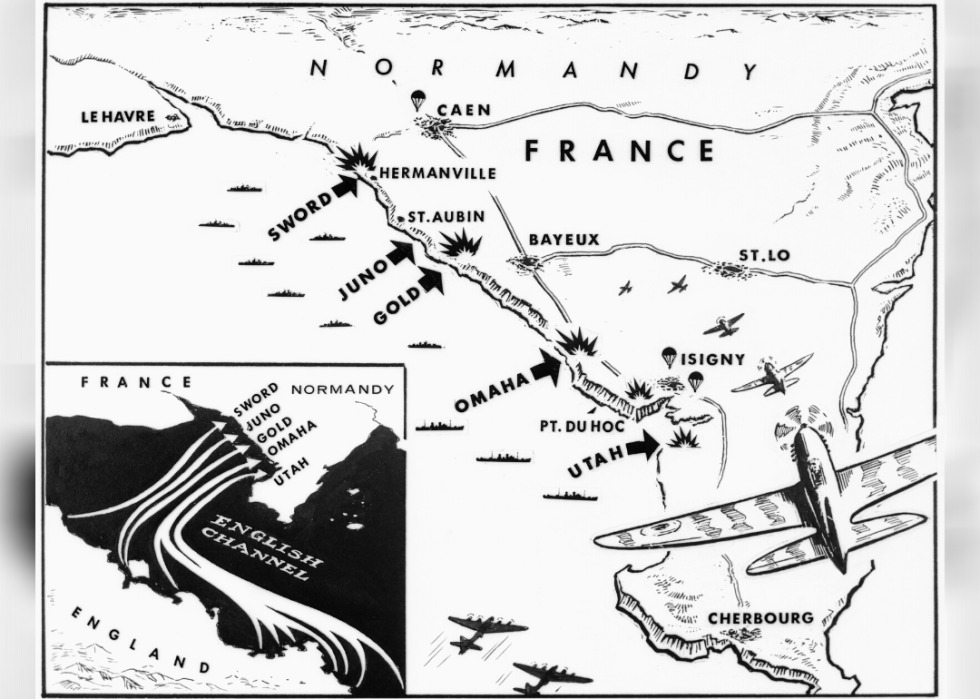

Forces landed on 5 code-named beaches

The landing zones for D-Day were code-named as part of the massive effort to maintain secrecy. The Americans landed at Omaha and Utah beaches, the British at Gold and Sword, and the Canadians and British at Juno Beach.

Omaha Beach was the hardest fought

The 1998 movie "Saving Private Ryan" depicts the events that took place at Omaha Beach, the deadliest of all five landing zones where the German defenses remained almost entirely intact. The first infantry wave at Omaha experienced the worst carnage of the D-Day campaign, with large sections of entire companies killed or drowned before ever reaching the shore or firing a shot. In the end, U.S. forces suffered 2,400 casualties on Omaha Beach.

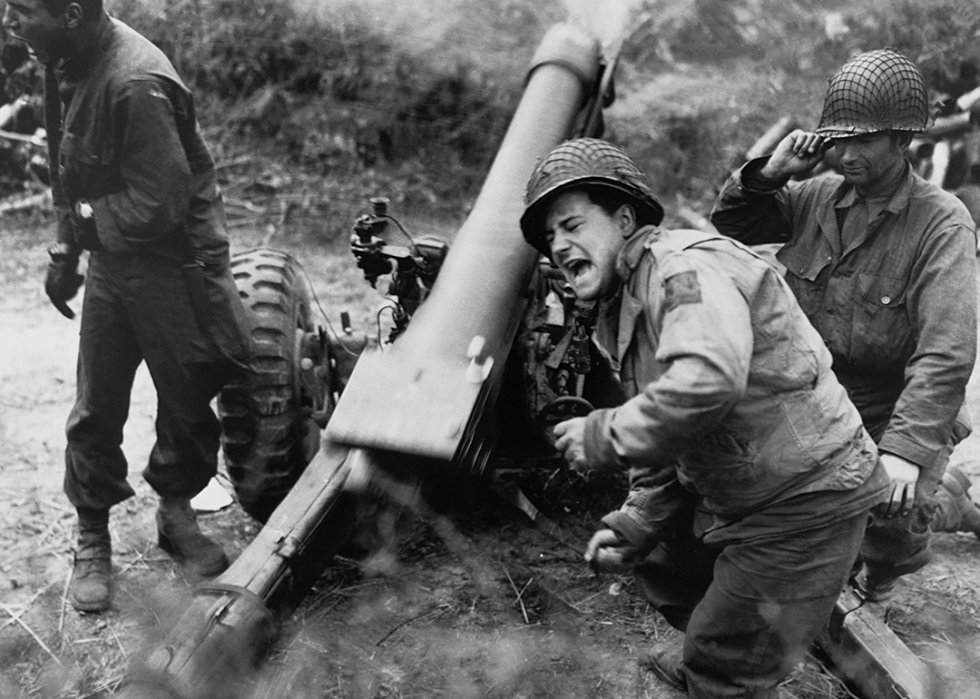

A massive bombardment preceded the invasion

The mighty Atlantic Wall and its sprawling coastal fortifications were the targets of a crushing Allied aerial bombardment that preceded the infantry invasion. On June 6, shortly after midnight, 2,200 Allied bombers attacked German positions to soften the landing zones for amphibious troops. One of the reasons Omaha Beach was so bloody was that thick cloud coverage in that area rendered the bombing campaign at Omaha ineffective, leaving enemy infrastructure—and guns—in perfect working order.

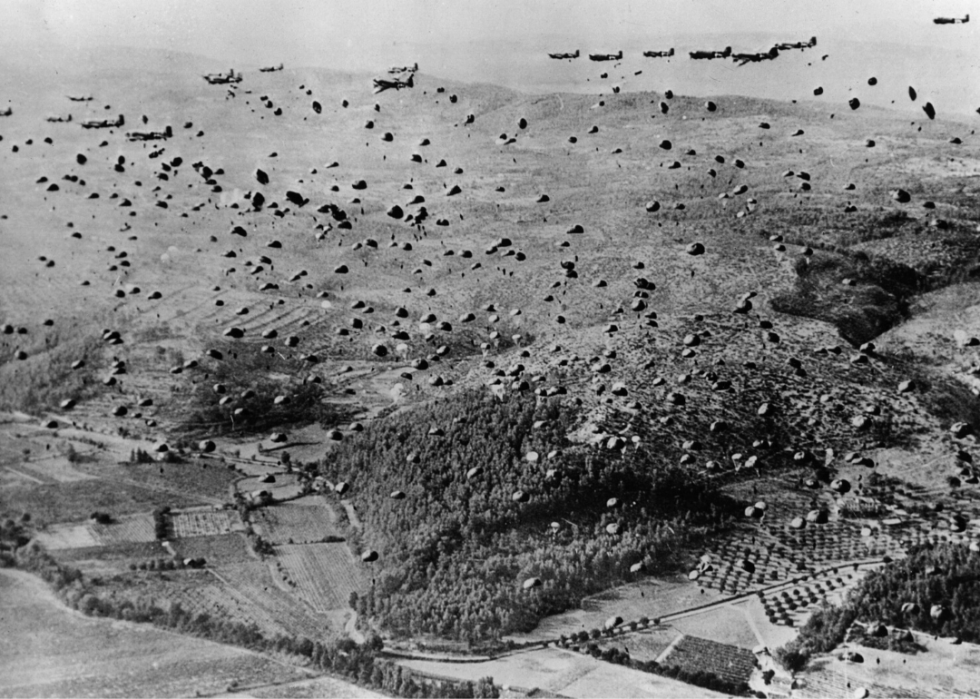

Thousands of paratroopers landed first

After the aerial bombardment, but before the beach landings, 24,000 American, Canadian, and British paratroopers parachuted in behind enemy lines to secure the beaches' exits. The same heavy cloud coverage that hindered the Omaha Beach bombardment also foiled the paratroopers. Many units ended up far away from their intended landing zones amid the chaos.

Canadian forces captured the most ground

The Canadians attacking Juno Beach suffered carnage similar to what the Americans experienced at Omaha, particularly the first wave of troops, many of whom died before reaching the shore thanks to rough seas and relentless Nazi artillery. In the end, however, it was the Canadians who captured more towns, more strategic positions, and more ground than any other battalion.

The operation had a code name

Like the beaches and landing zones themselves, the invasion had a code name. What history knows as the Battle of Normandy was called Operation Overlord by Allied planners. The initial beach landings on D-Day were dubbed Operation Neptune.

D-Day involved nearly 7,000 Allied ships…

The beach invasion involved an unprecedented 6,939 ships and other vessels. Eighty percent of them were British.

…and more than 11,500 Allied aircraft

The D-Day operation also included 11,590 aircraft. They supported the naval fleets, dropped off paratroopers, conducted reconnaissance, and bombarded Nazi defensive positions.

There were 73,000 American troops at D-Day

In addition to American soldiers, 61,715 British Allied liberators and 21,400 Canadian troops fought in D-Day. In total, 156,115 Allied troops stormed the beaches of Normandy.

Comanche 'code-talkers' joined the siege

The U.S. government enlisted the service of now-famous Comanche "code-talkers" in both World War I and World War II. Using their native tribal language, they developed a secret messaging code that proved unbreakable for the Germans. Thirteen of these code-talkers were among the Allied soldiers who landed at Normandy.

The Allies faced 50,000 German defenders

Roughly 50,000 Germans defended the massive structures of the Atlantic Wall. Heavily armed and ordered to hold their ground at all cost, German forces were among the hardest and most seasoned veterans in the Nazi war machine.

The battle lasted until August

D-Day was only the start of the long and brutal Battle of Normandy, which raged until the end of August. In terms of average daily casualties, the campaign was bloodier than the infamous Battle of the Somme during World War I.

The exact number of fallen is unknown

It's believed that 4,413 Allied troops were killed on D-Day. But reliable records of German fatalities are much harder to come by. Estimates range between 4,000-9,000 Germans were killed on June 6, 1944.

Most Allied troops arrived after D-Day

Between June 6 and August 21, more than 2 million Allied troops landed in northern France. Relative to the larger battle of Normandy, the soldiers who participated in the D-Day landings represented only a small percentage of the overall combatants.

The operation led to the liberation of Paris

On August 8, the Germans staged a last-ditch counterattack repelled by Allied forces, marking the beginning of the end of the Nazi occupation of France. The Allies finally broke out of Normandy a week later on August 15, and on August 25, they liberated Paris.

A memorial cemetery sits on US soil in France

Most of the 9,387 Americans buried at the Normandy American Cemetery were killed on D-Day or in the early stages of the Allied fight to establish a beachhead. It's one of 14 permanent World War II military cemeteries the American Battle Monuments Commission built on foreign soil. It sits on land granted to the United States by France.

Families fought—and died—together

Among those buried at the Normandy American Cemetery are 33 sets of brothers who are buried beside each other. A father and son are also buried there together.

Around 14,000 corpses were returned home

There used to be far more fallen servicemen buried at the cemetery and in the surrounding region. The remains of roughly 14,000 people were returned home at the request of their families.

The Allies lost more than 11% of their troops

Of the 2 million-plus Allied liberators, the Battle of Normandy resulted in more than 226,386 casualties. Of those, 72,911 were either killed or missing, and 153,475 were wounded.

German casualties exceeded 240,000

The Nazi defenders suffered similar losses, with German casualties topping 240,000 throughout the Battle of Normandy. The Allies also captured more than 200,000 German prisoners.

The action was far from consistent

Allied troops on D-Day had radically different experiences depending on where they landed. In some places along the 50-mile front, there were almost no casualties at all. In other places, casualty rates rose as high as 96%.

The tide was a double-edged sword

The planning for an operation of this magnitude required a meticulous consideration of an uncountable number of details and variables. If the attack happened at high tide, for example, landing craft might hit submerged German obstacles. If the Allies landed at low tide—the course that planners eventually chose—they would avoid those obstacles, but troops would be forced to sprint the length of the beach with no cover under relentless fire.

The beach was a minefield

The most enduring images of D-Day are of exposed Allied troops being cut down by machine gun fire from elevated German positions. While machine guns certainly caused a hideous number of casualties, death and danger didn't only come from above. It's estimated that the Germans planted roughly 4 million landmines on the Normandy beaches, making every footstep a potential catastrophe for Allied forces.

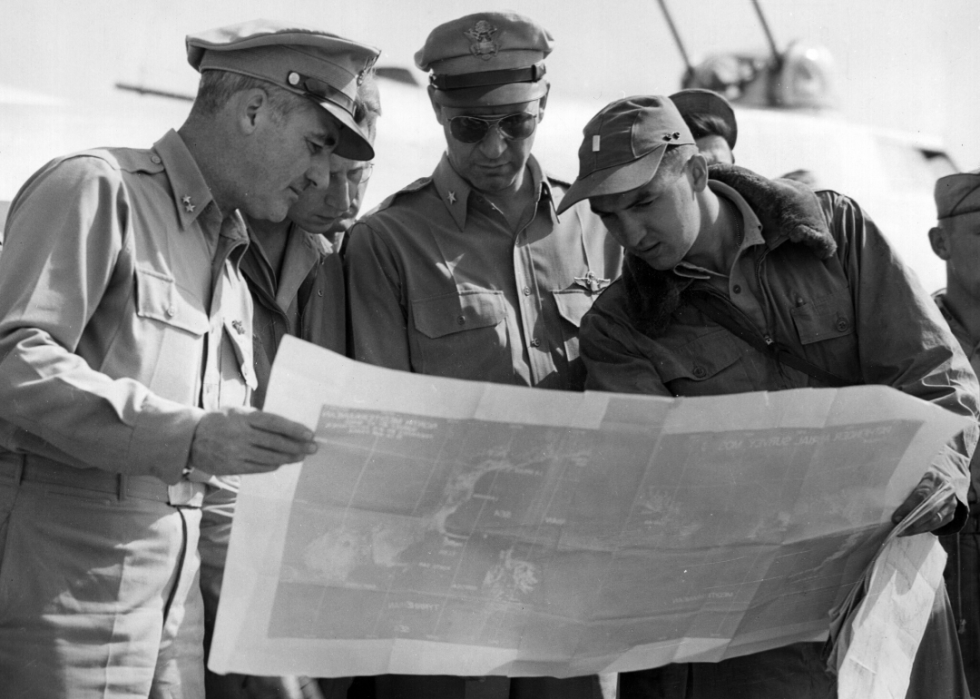

D-Day was the result of trial and error

U.S. and British commanders reviewed plans for Operation Overlord at the Quadrant Conference in 1943. However, the seeds of D-Day were planted the year before. In 1942, the Allies suffered heavy losses during a failed raid on a French port, a moment that persuaded military strategists to plan for future beach landings.

The Germans almost thwarted D-Day

The Germans knew that a sea-based attack in northern France was imminent; they just didn't know where. They concentrated their forces near Calais because it was at the English Channel's thinnest point. It was the logical move, but Supreme Allied Commander Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower was a step ahead and chose Normandy because it was west of that obvious landing point.

It was supposed to happen a month earlier

The D-Day invasion was originally planned for May 1944. However, there weren't enough landing craft ready, though, so Eisenhower had to postpone the attack for a month.

Nature played a pivotal role

Poor weather almost caused another delay in June, but this time, Eisenhower decided to attack anyway. Relying on natural illumination, the Allies had to invade during a full moon, and by June 5, that window was beginning to close. Eisenhower ordered the attack for the following day both despite and because of the bad weather; not only did they still have the crucial full moon, but angry skies kept German planes grounded.

Higgins boats whisked many troops to shore

Fleets of now-iconic Higgins boats ferried most men ashore on D-Day. Technically called LCVP, for "landing craft vehicles and personnel," the vessels were designed and built by an ambitious and eccentric Irish American industrialist named Andrew Higgins. Made from wood and steel, Higgins boats were simple, practical, reliable, and easy to mass produce. In 1964, Eisenhower famously credited Higgins and his efforts with winning the war.

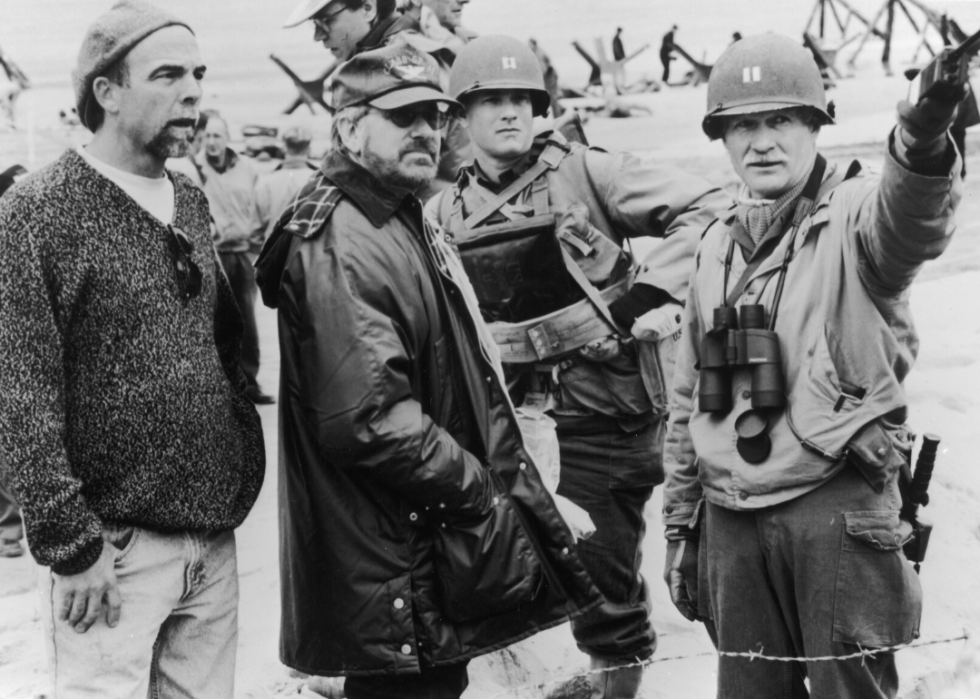

D-Day films have become part of American popular culture

The Normandy invasion has been the subject of countless movies and television series, some of which are considered to be among the finest films ever made. At the top of nearly every D-Day movie best-of list is Steven Spielberg's "Saving Private Ryan." In one of the most notorious episodes in Oscars history, the celebrated Normandy epic lost out to Harvey Weinstein's "Shakespeare in Love" for Best Picture at the 1999 Academy Awards after the now-disgraced producer muscled his period piece through with a campaign of backroom bullying and politicking.

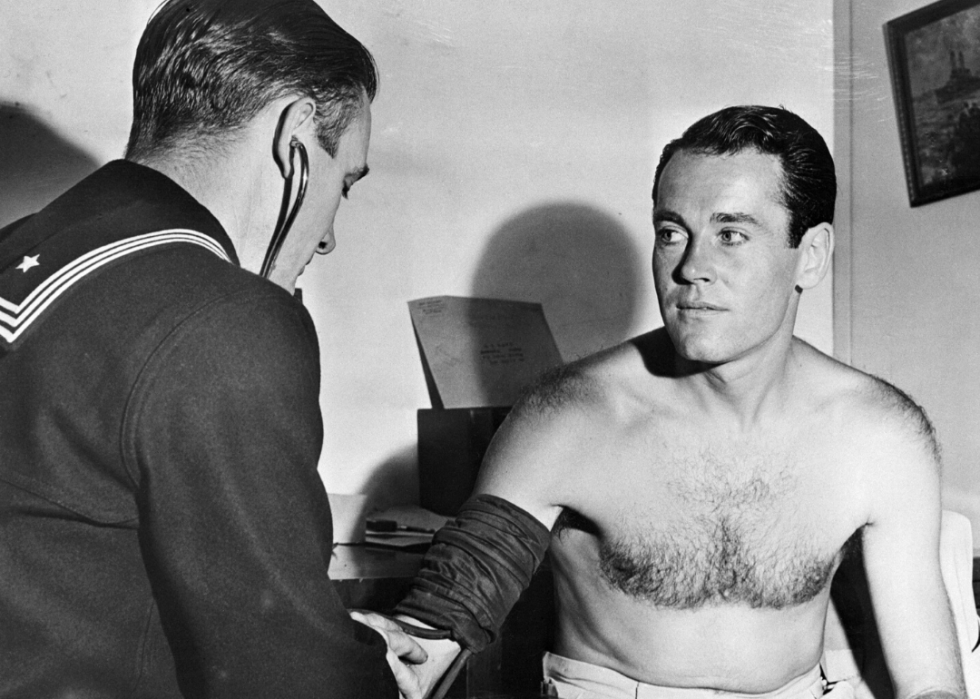

A D-Day movie star served on D-Day

Actor Henry Fonda was 37 in 1942 when he enlisted for military service. On D-Day, he served as quartermaster on the USS Satterlee, an American destroyer. He went on to star in "The Longest Day," a 1962 film that, along with "Saving Private Ryan," is consistently ranked near the top of lists of best D-Day movies—and war movies in general.

Many other famous people served on D-Day

Yankees catcher Yogi Berra took part in the D-Day invasion, as did author J.D. Salinger and slain civil rights activist Medgar Evers, who supported the invasion as part of a segregated unit. Golf great Bobby Jones was 40 when he successfully petitioned his Army Reserve commander to allow him to join the fray. Oscar-winning British actor David Niven was among the first officers to land, winning a U.S. Legion of Merit Medal. Before he played Scotty on "Star Trek," James Doohan sustained six bullet wounds and lost his middle finger on Juno Beach. Actor Charles Durning, thrown into the first wave at Omaha Beach, won a Silver Star and a Purple Heart and was the sole survivor from his landing group.

Gargantuan supply shipments preceded the invasion

To prepare for the landings, the Americans shipped 7 million tons of supplies from the U.S. to a staging area in England. Among the haul was 450,000 tons of ammunition.

17 million maps were needed

Allied commanders planned meticulously for years, photographing the area from the air and painstakingly cataloging every detail of the landscape. In the end, war planners created 17 million maps to support D-Day operations.

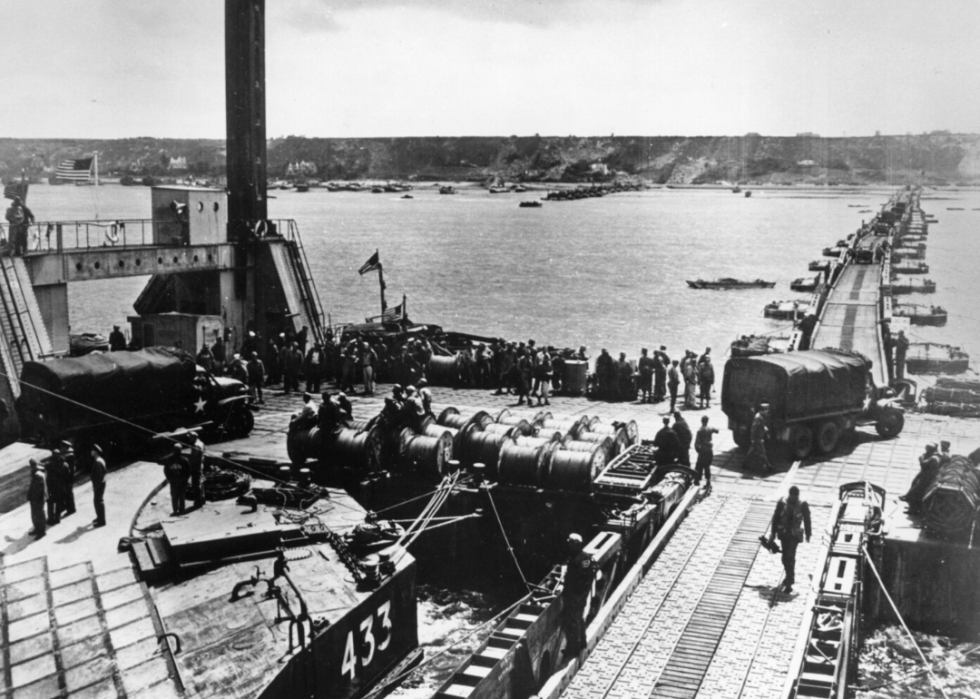

The landings opened a supply line

By establishing a beachhead, the Allies opened a supply chain that allowed desperately needed resources to flow into France. By June 11 (D+5), 104,428 tons of supplies, 54,186 vehicles, and 326,547 troops had followed in the footsteps of the first infantrymen to hit the shores.

Artificial harbors supported the supply lines

In order to accommodate the massive influx of people and things, the Allies constructed two enormous artificial pre-fabricated harbors called the Mulberry Harbours. 55,000 workers spent six months getting the job done, pouring 1 million tons of concrete.

The Army attacked with 6 divisions

The 1st, 4th, and 29th Infantry Divisions were called to serve in the D-Day landings. The 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions were there too. Finally, a massive collection of nondivisional units served at Normandy as well.

500 gliders took to the air

Five hundred primitive but effective motorless gliders were launched to support the paratroopers and their bungled parachuting mission behind enemy lines. Glider infantry carried not only weapons but badly needed signal and medical units. Although the pilots were technically Army Air Corps personnel, they became infantrymen the moment their plywood aircraft hit the ground.

A separate battle raged high above the beach

As part of their Atlantic defenses, the Germans placed artillery pieces atop Pointe du Hoc, 100-foot cliffs overlooking Omaha and Utah beaches and the English Channel. Those artillery units could have annihilated Allied forces landing on the beaches below, but U.S. Army Rangers scaled the cliffs, seized the guns, and held the terrain against significant German counterattacks. The Rangers' efforts to secure Omaha Beach's left flank came at a tremendous loss of life.

The Atlantic Wall was breached in a day

The 80 miles of the German Atlantic Wall that stretched along the coastline of France were believed to be impregnable by some commanders. It fell in a single day—on June 6, 1944.

The day produced 12 Medals of Honor

The Medal of Honor is the highest award that the U.S. Armed Forces can bestow. Of the thousands who fought and died, 12 men received Medals of Honor for their heroics on D-Day. Nine of them were given posthumously.

Heavy packs encumbered troops

The landing troops, most of whom were younger than 20, carried packs weighing around 80 pounds. This proved to be a fatal burden for many who evacuated their Higgins boats in deep water. Those who made it ashore had to run hundreds of yards under blistering fire while carrying the already heavy—and now waterlogged—packs.

Boat ramps served as shields

Higgins boats used cheaper, lighter wood where possible, but designers used steel for the landing ramps that served as shields protecting troops from relentless machine gun fire—until they opened. One D-Day veteran compared the sound of bullets hitting the closed ramps to the clanking of a typewriter.

1 Black combat unit participated

The U.S. Army was segregated during World War II, and Black units were largely relegated to supporting roles and manual labor. On D-Day, however, a single segregated Black unit participated in the landings: the 330th Barrage Balloon Battalion.

That unit's medic is an unsung hero

Waverly B. Woodson Jr. served as a medic with the invasion's only Black unit and, despite being badly injured himself, saved hundreds of lives—including four men he rescued from drowning. He ignored the constant threat of death and his own potentially mortal wounds while establishing a medical station where he treated at least 200 men for 30 hours before collapsing from exhaustion and his own injuries. In recent years, his incredible story emerged, leading to calls for the military to award him the Medal of Honor.

Although that recognition has not yet been granted, Woodson was posthumously awarded the Bronze Star Medal and the Combat Medic Badge in 2023, and in 2024, he received the Distinguished Service Cross—the Army's second-highest award for valor.

Germany surrendered less than 1 year after D-Day

The Normandy landings breached a continent the Nazis had transformed into a fortress. It was the beginning of the end for Nazi Germany and a major turning point in the war. On May 7, 1945—less than one year after D-Day—Germany surrendered unconditionally to the Allies.

Copy editing by Meg Shields.