As more states adopt traffic enforcement cameras, here's where New York stands

This story originally appeared on The General and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

As more states adopt traffic enforcement cameras, here's where New York stands

Technology is helping some states and cities crack down on dangerous driving.

In particular, traffic cameras have spread throughout the nation. These are intended to ensure that drivers fully stop at red lights and maintain posted speed limits, which help motorists avoid major safety threats. About 340 communities throughout the United States have red light cameras, and 278 have speed cameras, according to the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety.

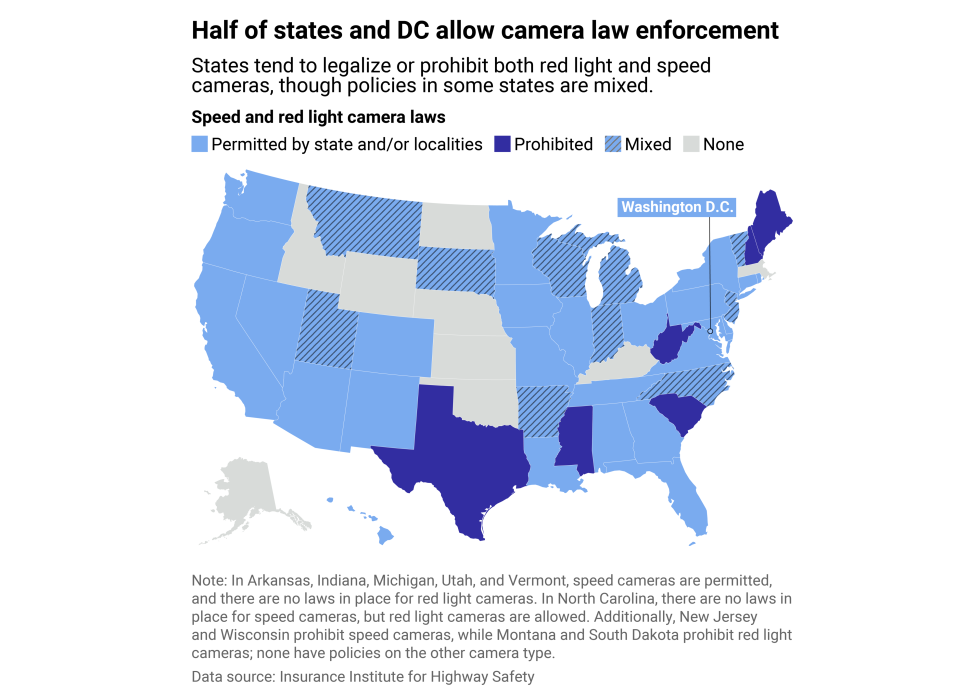

Automated camera enforcement programs are not everywhere, however, and some states even prohibit them. The General used data from the nonprofit Insurance Institute for Highway Safety to map state policies on the use of red light and speed cameras, as well as analyze their prevalence across the nation.

Case studies have shown the efficacy of traffic cameras. New York City was the first to implement a red light camera program in 1992. In October 2024, the state of New York announced it was expanding its red light camera programs, citing a 73% drop in red light running and related crashes where they were installed.

Following its own example, New York City in 2013 started adding speed cameras to school zones and realized immediate results. In those school zones, speeding fell by 63%, crashes by 15%, and fatalities by 55%. The cameras issued an average of 104 speed violations per day in their first month, a figure that fell to 51 per day by the end of their first year in service. The vast majority of drivers didn't receive a second fine after their first offense—signaling a change in driver habits.

School zones are a common site for speed cameras, but the devices are also useful in residential neighborhoods and construction zones. When installing red light cameras, jurisdictions tend to make data-driven decisions about where to place them; factors include red light violations, intersection crash data, and pedestrian injuries.

Read on to see how New York compares to others in traffic camera laws, and check out the national analysis here.

States split on use of cameras for traffic safety enforcement

Where New York stands on traffic enforcement:

- Speed camera laws: Permitted by state and/or local law

- Red light camera laws: Permitted by state and/or local law

Red light and speed cameras are typically permitted by state law and city, county, or area ordinances. Their use, however, is not ubiquitous.

The spread of these automatic traffic enforcement cameras—especially red light cameras—has received major backlash. Critics say the cameras are an example of policing for profit or that they don't do enough to protect pedestrians.

Eight states prohibit red light cameras, and the same number doesn't allow speed cameras. Both types are illegal in six states: Maine, Mississippi, New Hampshire, South Carolina, Texas, and West Virginia. Texas Gov. Greg Abbott signed a ban into law in 2019 after years of opposing them as the state's attorney general. His office cited a study by two economics professors who determined that red light cameras increased rear-end accidents—a common complaint from opponents. On the other hand, a study by the IIHS showed that red light cameras reduce fatal crashes at monitored intersections.

Prior to the Texas ban, red light cameras in the city of Plano drove accidents down by a third and simultaneously raised money for trauma centers and traffic safety programs. State police officials had also supported the cameras.

Bias is another point of contention in automated traffic enforcement. Proponents say that cameras are equitable, as they follow consistent rules and apply the same repercussions for all vehicles running red lights or speeding, eliminating any prejudiced application of laws by police officers.

However, the issue of where cameras are placed can still contribute to and reinforce discrimination in law enforcement. For instance, a ProPublica series—backed up by University of Illinois Chicago research—found that Chicago's automated red light and speed camera programs disproportionately ticketed Black and Latino motorists, with dire financial consequences. Meanwhile, the city of Rochester, New York, ended a six-year red light camera program in 2016 after determining that it unevenly fined low-income residents.

Red light and speed camera trends have diverged

Even the studies that showed discrimination also found that the cameras improved safety. As with any form of law enforcement, automated cameras are a tool with benefits and drawbacks that must be weighed in community decisions.

ProPublica reported that Chicago would review cameras at locations where evidence suggested they didn't reduce crashes but that the city wasn't considering cutting or downsizing the program. Federal Highway Administration guidance on speed cameras provides that they should supplement other efforts, including more traditional enforcement measures, engineering, and education, to "alter the social norms of speeding."

The number of red light cameras has actually decreased drastically over the past decade amid community opposition and lack of financial viability as well as reductions in citations (i.e., fewer people running red lights). Meanwhile, the number of communities with speed cameras has continued to grow—and helped alter dangerous driving habits.

Federal regulations say states could spend up to 10% of their allocated Bipartisan Infrastructure Law funds on automated traffic enforcement measures. This means over $1.5 billion in federal funding is available to expand these technologies. But since not all states allow them—and considering other highway safety initiatives that could be funded instead—the real investment will likely be much smaller.

Still, as states and jurisdictions deal with mounting speed-related fatal crashes, which remain at the highest levels in over a decade following a 2020 peak, Americans should expect to encounter enforcement cameras in their travels.

This story features data reporting and writing by Paxtyn Merten and is part of a series utilizing data automation across 50 states and Washington D.C.