Dark Forest: A look inside controversial wilderness therapy camps

Dark Forest: A look inside controversial wilderness therapy camps

In 2007, 17-year-old Sarah Stusek woke up at 4 a.m. The lights were mysteriously turned on. Her phone was gone. She looked up to see a man and a woman hovering over her on either side of the bed. They told her to get dressed and that they were taking her somewhere. They didn't explain where.

The pair gave her an ultimatum: act civil in an airport, or prepare for a long car ride. She chose the former. Stusek was whisked away from her suburban home in Annapolis, Maryland, to Three Rivers, a wilderness therapy camp located in the Montana backcountry. For several months, she would sleep in tents and build fires from scratch with other teens.

This kidnapping was not only orchestrated by Stusek's parents, but entirely legal due to a lack of regulations.

In the United States, thousands of pre-teens and teens have their rights signed over to "therapy camps" in the troubled-teen sector, a largely unregulated, multi-billion dollar industry aimed at rehabilitating youth labeled as "troubled" or "delinquent" by parents, guardians, psychiatrists, or school officials.

Whether the concern is substance abuse, poor grades, or mental health, much of the troubled-teen industry packages its "tough love" approach as a cure-all solution to desperate parents.

While institutions that fall under the broad category of therapy camps come in many forms, the most rustic — and inherently rural — are wilderness therapy camps. The Daily Yonder looked closely at the controversial practices employed by the wilderness therapy camp industry to treat troubled teens that, according to former campers and child welfare advocates, may do more harm than good.

The beginning of wilderness therapy camps

The idea of escaping to nature to clear the mind is not a new one, and this modern version associated with the troubled-teen industry has its roots in Utah.

In the 1960s, school officials at Brigham Young University developed a course called "Youth Leadership 480." The course, taught by then-undergraduate Larry Dean Olsen, aimed to help failing students gain readmission by learning outdoor survival skills on month-long backpacking trips in the Utah desert. Subsequently, the course garnered the attention of Utah County officials, who adopted its model to try to help juvenile delinquents. Some of Olsen's former peers, realizing the potential for profit, branched off and started their own private wilderness therapy camps.

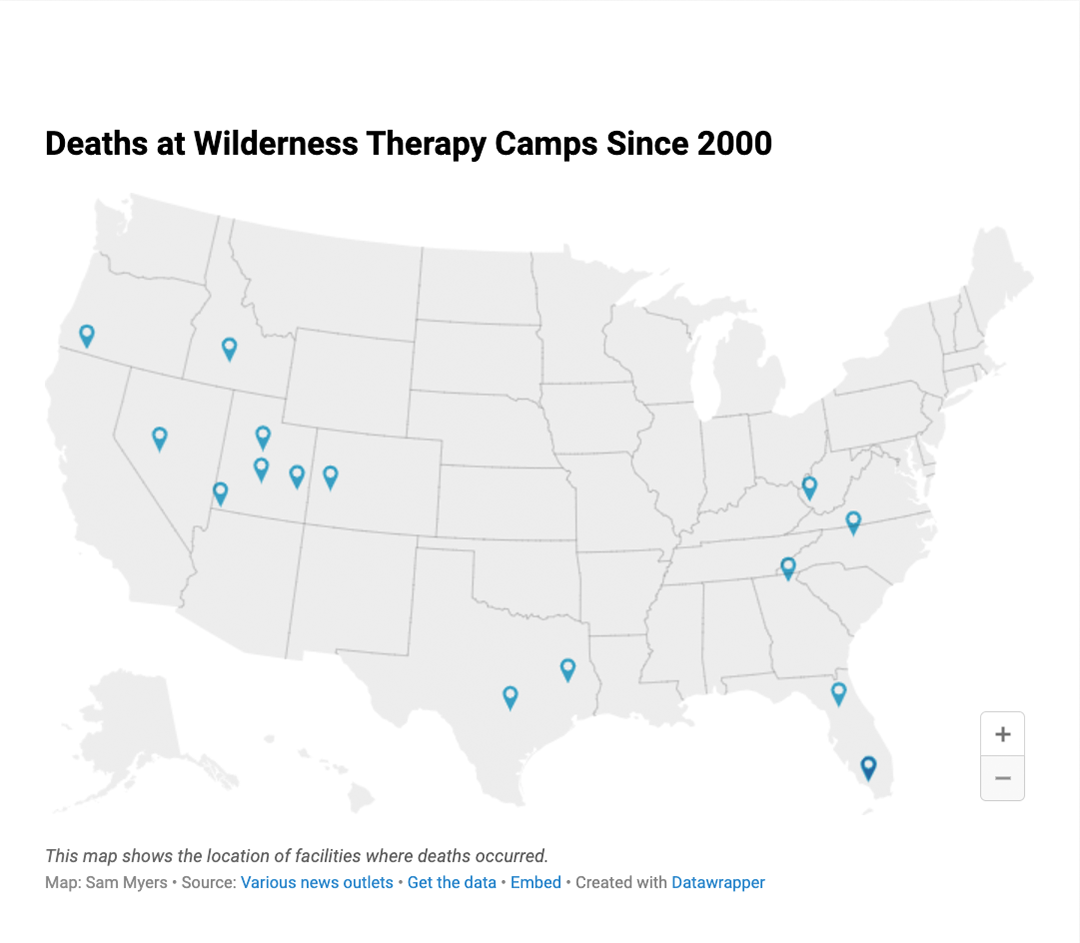

Over several decades, Utah's pristine natural beauty and loose regulations turned the Beehive State into an unofficial poster child for wilderness therapy camps and the troubled-teen industry. These camps can also be found nationwide, especially in the West and Southwest.

"There are other states that certainly have just as many bad facilities, but Utah for sure has gotten the most attention," said Meg Appelgate, co-founder and CEO of Unsilenced, an organization aimed at raising awareness of institutionalized child abuse in the troubled-teen industry.

When she was 15, Appelgate was abducted by two strangers in the middle of the night. She spent the next three-and-a-half years in two programs: the Intermountain Children's Hospital, a lockdown residential treatment center in Idaho, and Chrysalis, a therapeutic boarding school in northern Montana.

Uncovering abuse, death, and deceptive marketing

Like other branches of the troubled-teen industry, wilderness therapy camps eventually drew increased scrutiny.

In 2008, the United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) published an extensive report examining allegations of abuse, death, and deceptive marketing practices at residential programs nationwide. The report covered several deaths at wilderness therapy camps. In one instance, a 14-year-old at a Texas wilderness therapy program died of cardiopulmonary arrest after his hiking group got lost for hours in temperatures with a heat index near 105 degrees Fahrenheit.

Running away isn't an option, as trekking the Utah desert or the Montana wilderness is a herculean task for even the most seasoned survivalist. In 2014, a 17-year-old named Alec Lansing died of hypothermia after running away from a wilderness therapy camp in North Carolina.

There is no evidence that wilderness therapy camps effectively rehabilitate troubled youth. In 2006, Maia Szalavitz, a journalist who covers drugs, addiction, and public policy, published her book "Help at Any Cost: How the Troubled Teen Industry Cons Parents and Hurts Kids." In an interview with the San Diego Union-Tribune, Szalavitz went as far as to say that the practices used by these programs would be violations of the Geneva Convention for prisoners of war.

Digital deceit

It would be easy to mistake a wilderness therapy camp website for the visitors' page of a national park or a mountain resort. These organizations invest heavily in making their websites appealing to parents.

"You know, you look at these websites, you see horses and animals, and you get to go hiking, boating, skiing, rock climbing, and all this stuff. And they really make it look amazing. But in reality, what we're seeing is that those are just things on a website," said Appelgate about observations she's made in her work to stop institutionalized child abuse. "And yeah, they might get to see dogs or horses, but behind the scenes, what you think is going on really isn't."

The GAO's report showed that many programs employ deceptive marketing, including false statements and misleading representations of practices and policies.

This means parents are paying exorbitant amounts of money for experiences their children may not even be having. A survey of 28 wilderness camps conducted by All Kinds of Therapy found that sending a child to one of these programs for 30 days costs, on average, $19,934.

An alarming lack of care

"I was out in wilderness therapy for 72 days," said Kayla Muzquiz, who spent much of her childhood in the troubled-teen industry. "And unfortunately, they didn't take me to a doctor. I think if they did, they would have found that I had a thyroid condition. They didn't do any tests to see if there was anything wrong with us before sending us out into 'the field,' is what they would call it. But I almost died like three times. I woke up next to a snake, a copperhead, twice."

Muzquiz was sent to SUWS of the Carolinas, a wilderness therapy program in rural North Carolina.

"We would wake up every day and hike 10 miles with almost a 60-pound pack on our backs," Muzquiz added. "It was excruciating because I had an undiagnosed autoimmune disorder throughout my time in the troubled-teen industry. So while I was hiking, I was constantly in pain. And it wasn't just regular pain that ibuprofen or Tylenol could take care of; it was just my body attacking itself constantly. So, if you complained, you couldn't move up in levels or ranks in wilderness, so it was more like you just had to bite your tongue and kind of just roll with the punches."

It's tough to regulate the wilderness

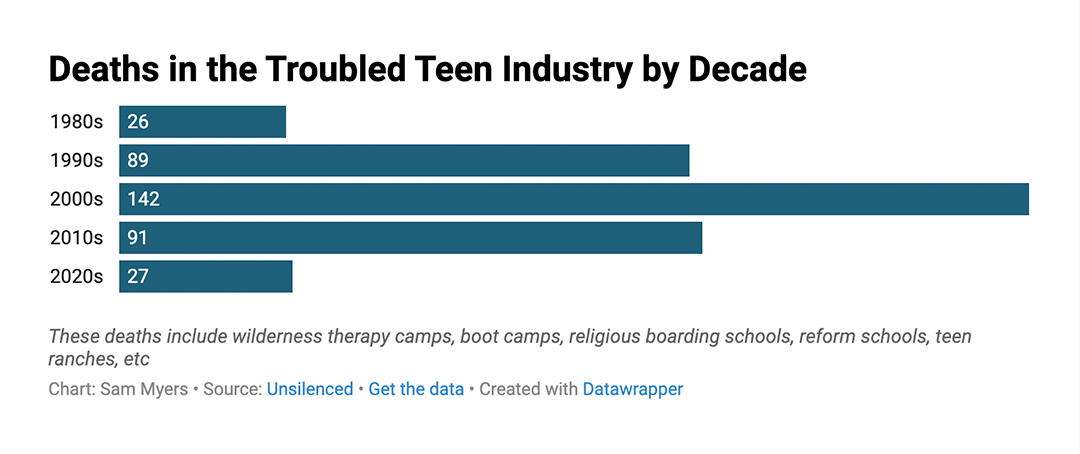

Even with a long paper trail of abuse and death, wilderness therapy programs have no federal oversight, leading to inconsistent, and mostly non-existent regulations at the state and local level.

"I think that another really hard part is that this [troubled-teen] industry was built decades and decades ago, without any foundation of regulation, reporting, governance, anything really," said Appelgate. "So, how do you regulate 100 years later, when it's a $23 billion industry, and we've got 120,000 to 200,000 kids being funneled into these facilities annually?"

On top of that, Appelgate said the placing of these camps in rural locations is not just about easy access to nature.

"Many of these programs strategically operate in very remote areas. The reason they do so is one, it's in the middle of nowhere, and kids can't run away. But also because they become the economy. And so, the entire town often depends on the jobs at that facility. So, you're not going to have your town really turning on you if you're helping the economy to that degree."

For many camps, young, naive college kids become a cheap labor source and bring money to the local economy.

This lack of regulation has created an "incestuous cycle" of corruption and abuse in Appelgate's eyes.

"Let's say a case of sexual abuse happens. What they'll do is just fire that person, and then tell the authorities they took care of it … but that facility isn't held accountable for having had that person there. So, that person will go and work at a different facility. And maybe the same thing happens. Maybe it doesn't. But we see this kind of moving and shifting within this industry. And furthermore, let's say the whole facility did something terrible, and they shut down. Well, what they usually do is rebrand under a new LLC – even if they're in the same building and do the exact same things."

Rebranding is a common practice for wilderness therapy camps, and Aspen Achievement Academy (AAA) is just one example. Opened in 1989 by the Aspen Education Group, AAA operated in Loa, Utah, right in the heart of Capitol Reef National Park. It didn't take long for the program to be mired in scandal.

According to research done by the organization Breaking Code Silence, a mother accused a therapist at the facility of assaulting and sodomizing her 14-year-old daughter in 1991. The therapist was fired, but it's unclear if they were criminally charged. Two years later, a 14-year-old boy attempted suicide by jumping off a 75-foot cliff. And in 2007, a 16-year-old boy died by suicide.

In 2011, Aspen Achievement Academy merged with another Aspen Education Group program and rebranded to Outback Therapeutic Expeditions. 34 years later, they're still operating.

Before arriving at SUWS of the Carolinas, Kayla Muzquiz attended New Leaf Academy, a boarding school in Hendersonville, North Carolina, that the Aspen Education Group owned. It closed in 2010.

"To me, it was really just a facade of a school. They tried to pass it off as an educational place that had therapeutic properties attached to it. But it was dehumanizing, and they would take everything away from you." said Muzquiz.

"Because the wilderness program is supposed to be worse than the boarding school, it's a punishment. It's something that they tell you, 'Hey, we're going to send you to the wilderness. We're going to tell the higher-ups to consider wilderness for you.' And it's basically being removed from the community of kids and staff." said Muzquiz.

Making headway at the state level

For years, lawsuits were the only way to shut down these programs. But recently, momentum for governmental regulation has built in some states.

In March, Appelgate testified in front of the Montana State Senate to support HB218, which would revise program practices and provide additional licensing requirements. HB218 passed with bipartisan support and was signed into law on May 17, 2023.

In 2021, Oregon was the first and only state to enact regulations on the practices of teen kidnapping services – prohibiting handcuffs and requiring registration with the state's Department of Human Resources. For many, this legislation, spearheaded by Oregon Senator Sara Gelser Blouin, is a pivotal win.

"She has done a great job reforming Oregon," said Appelgate. "I forget what number of teen transports they had before the bill. Now, it's like one. It has completely put it out of business, which is just fantastic. She's done a great job at shutting down little aspects of the pipeline that lead to it. Now, Oregon isn't a very big send-out state."

Sarah Stusek, Meg Appelgate, and Kayla Muzquiz agree that their own kidnappings were the most traumatic part of the whole experience. And Stusek, like many former camp goers, took to social media to share that particular story. The TikTok detailing her kidnapping has millions of views.

While Stusek said there were also some positive aspects of the wilderness therapy camp she attended, she still thinks practices like planned kidnapping should be outlawed.

"I do think that they should be banned. It's not a good practice at all … I think the wilderness, in general, and being outside is very healing for someone, but it has to be in the right circumstances. It can't be a power struggle thing. You have to want to do it."

This story was produced by The Daily Yonder and reviewed and distributed by Stacker Media.