New vehicle costs are tempering but remain high relative to income

This story originally appeared on The General and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

New vehicle costs are tempering but remain high relative to income

Buying a new vehicle has become much more expensive since the COVID-19 pandemic threw a wrench into automotive manufacturers' supply chains. New vehicle prices have been rising at the fastest clip in recorded history since the spring of 2021.

That rapid rise in costs began to slow, finally, this year. But that doesn't mean buying a new vehicle is getting cheaper—it's just not getting more expensive as quickly as it has been for the last several years.

The General used data from Cox Automotive and Moody's Analytics to examine new vehicle affordability for American consumers. The index considers actual sale prices after any discounts or negotiations rather than simply the MSRP. It also factors in a 10% down payment plus interest and assumes a 72-month term for financing.

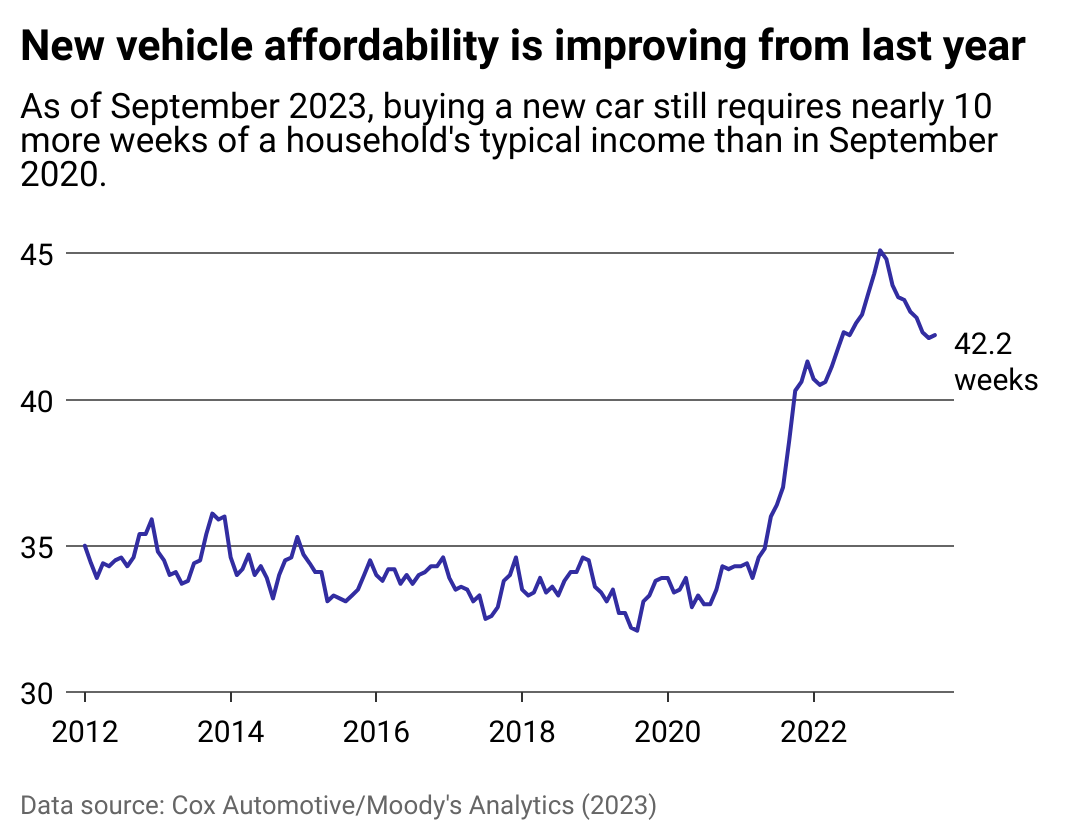

From 2012-2019, an American household earning the median income could purchase a new vehicle with the equivalent of about eight months of income. Today, buying a new car requires closer to 9.5 months' worth of income.

This represents a shift that's happened in just three years whereby new vehicles have moved further out of reach for the typical American family thanks to a combination of rising prices for vehicles and higher costs to borrow money.

The cost of purchasing a new vehicle relative to income is falling from a decade high

Throughout the 2010s, the cost of purchasing a new vehicle remained relatively stable for American households, rising cyclically around the end of each year. However, the pandemic created a disruption in the vehicle manufacturing industry that would reverberate for years.

The first year of the pandemic kept Americans at home, attempting to avoid the worst outcomes of the little-understood COVID-19 disease spreading through the country. By spring 2021, however, Americans were able to get early vaccines, allowing them to hit the roads again to return to workplaces, visit family, and travel for leisure to places where leisure industries were still operating.

The uptick in mobility that year meant Americans needed cars again, and demand for vehicles shot back up to what was typical. But manufacturers weren't ready. Not only had their assembly plants been shut down sporadically as infections spread through them, but a shortage of computer chips hampered production levels. The mismatch between demand and availability of new vehicles meant dealerships and manufacturers could charge more.

That trend propelled the prices for new vehicles to record highs before plateauing this spring. In November, the number of unsold new vehicles on lots rose 62% over the same time in 2022.

"The supply issues that started in 2021 appear to have passed as most brands have seen their availability improve substantially," Cox Automotive senior economist Charlie Chesbrough said in a statement this month.

But even as more vehicles are available, fewer Americans are buying in the face of higher interest rates for car loans. Sales have been weaker, contributing to a decline in prices that could continue into the holiday months.

"As we enter the holiday sales season, greater discounting from the automakers seems likely," Chesbrough said.

Story editing by Ashleigh Graf. Copy editing by Tim Bruns.