As nursing home costs rise, here's where private payers are footing more of the bill

This story originally appeared on Incredible Health and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

As nursing home costs rise, here's where private payers are footing more of the bill

Professional care for older adults is expensive, no matter what type of care they receive. Whether it's care at home, a residential facility, or a nursing home, it's a cost that hits families hard.

According to a 2021 survey by Genworth, the national median price Americans pay for a home health aide is over $61,000 per year, and that's the most affordable among all continuous care services for older adults. At the other end of the price spectrum, the median costs of a semi-private room at a nursing home are around $7,908 per month, which adds up to about $94,900 annually. That's 2.9% higher than the median cost five years ago.

With baby boomers—the second-largest adult generation—on their way to passing the age of 65 by 2030 according to the Census Bureau, planning for elder care is top of mind for many families.

Nursing homes—one of the most popular types of elder care—are live-in facilities that provide daily medical care, meals, supervision, and rehabilitation services for older adults. Most nursing home residents need ongoing care due to physical or mental health conditions. Nationally, 62% of nursing home residents rely on Medicaid as their primary payer, 13% on Medicare as their primary payer, and the remaining 25% either cover the costs from their own pockets or rely on private insurance plans. Other options for prepaid coverage are long-term insurance plans and health savings accounts.

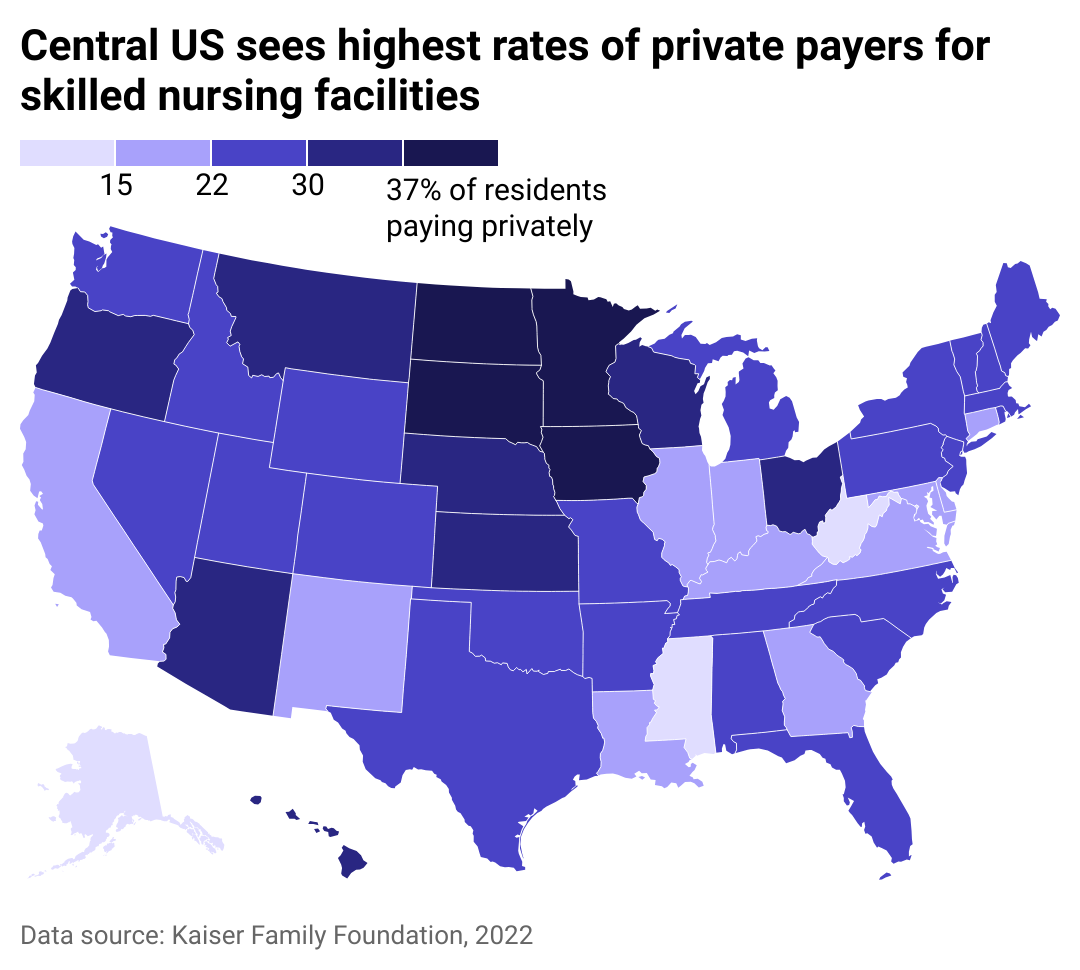

Incredible Health used Kaiser Family Foundation to look at states where nursing home residents primarily rely on private payments, whether from their own pockets or long-term care insurance, amid rising costs nationwide.

How Medicaid and Medicare work

The American Aging Council, an organization that provides free Medicaid planning assistance, warns that eligibility criteria are complex, with every state having unique requirements that continually change.

Income limits are applied differently to single and married applicants. A 65-year-old single person cannot earn more than $2,742 monthly to qualify for Medicaid. When both spouses request the coverage, married applicants can have a combined maximum income of $5,484 per month.

And there are limits on the assets a Medicaid recipient can own—as well as caps on assets their spouse can own if only one is applying for assistance from the program, which federal and state money funds.

Medicare, by contrast, does not have financial eligibility requirements. Instead, it is a federally funded health insurance program that covers people 65 or older and can also include younger people with certain medical conditions. Medicare participants can choose from several coverage options. However, Medicare only covers nursing home stays under specific circumstances, typically associated with recovery from surgery or other procedures or rehabilitation work like physical or occupational therapy.

The rising costs of senior care drastically affect the middle class, who usually have higher incomes than the maximum allowed by Medicaid but still not enough to pay the monthly costs of specialized geriatric services that Medicare won't pay. According to a 2019 study in the journal Health Affairs, the middle-class senior population will double from 7.9 million to an estimated 14.4 million by 2029—and they won't have the financial resources to pay for private senior care. Savings, properties, and business equity can quickly run short when elders pay for their care or seek help from other relatives.

Private long-term care insurance plans can help people prepare for the costs of aging without financially burdening family members. When shopping for long-term care insurance, besides asking fundamental questions about coverage and premiums, request information about entry and exit age, waiting periods, coverage for chronic and degenerative illnesses, and daycare services.

Where residents rely more on private plans

Minnesota has seen a rise in nursing home costs faster than the 3.25% national average. It has grown 10% over the past five years, reaching $11,601 for a semi-private room in 2022, according to Genworth. The national average cost is $7,908.

Currently, 37% of Minnesotans in nursing homes pay their own way or rely on private insurance plans, according to data from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Most states have seen costs grow close to the national average. However, other states with rapid cost growth, like West Virginia at 7% and Delaware at 5%, have a more significant share of residents who rely on Medicaid.

States with lower average household incomes, such as Mississippi—where relatively few older adults pay privately for their nursing home care—also struggle to meet other health and quality of life goals.

In more than 20 states, most in the central U.S., West, and Northeast, 22% to 37% of nursing home residents pay privately for geriatric daily care

Data visualization by Emma Rubin. Story editing by Ashleigh Graf, Jeff Inglis, and Kelly Glass. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.