From strikes to labor laws: How the US adopted the 5-day workweek

This story originally appeared on Firmspace and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

From strikes to labor laws: How the US adopted the 5-day workweek

It’s hard to imagine a world where Fridays don’t start the weekend, but the two-day weekend only rose to popularity in the 20th century.

The five-day, 40-hour workweek became part of American labor law partly due to Henry Ford. In 1926, the founder of the Ford Motor Company took his six-day-a-week operation down to five days per week, with no changes in employee compensation. He believed doing so would make his workers more productive—and more inclined to spend money during their downtime. With days off, people would have more time for leisure activities and shopping, spending their earnings, perhaps, on vehicles. This landmark change made Ford one of the first companies in the nation to set the standard of a five-day workweek.

When the 1929 stock market crash crippled the world economy, the resulting Great Depression led to mass strikes in response to rising unemployment and poverty, among other troubles. Backed by lawmakers within the federal government who realized labor laws needed to change, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Fair Labor Standards Act into law in 1938. This set specific restrictions and bylaws regarding labor, including the right to a minimum wage and “time-and-a-half” overtime pay for any time one worked in excess of 44 hours each week.

After this landmark labor law, policies would continue to change. In 1940, when the Fair Labor Standards Act was amended to bring the overtime threshold down to 40 hours per week, the 40-hour workweek and two-day weekend became officially mandated across the United States. Today, discussions of a four-day workweek have surfaced after the COVID-19 pandemic led to businesses exploring more flexible remote and hybrid working environments. In order to contextualize how the nation’s approach to labor has evolved, Firmspace examined historic milestones that led to the five-day workweek, from strikes to legislation.

Companies around the world have since started experimenting with the application of a four-day workweek again, with some making the shift permanent. The United Arab Emirates, for example, became the first nation in the world to adopt the concept of the four-and-a-half-day workweek, which went into effect on Jan. 1, 2022. Belgium is one of the most recent countries to try out the four-day workweek and the U.K. has invited companies to participate in a national trial to determine if a four-day workweek mandate would be viable. There are companies even in the U.S. that have just implemented four-day workweeks, with others planning trials for reduced work hours.

Read on to learn how the workweek has changed in the U.S. throughout history.

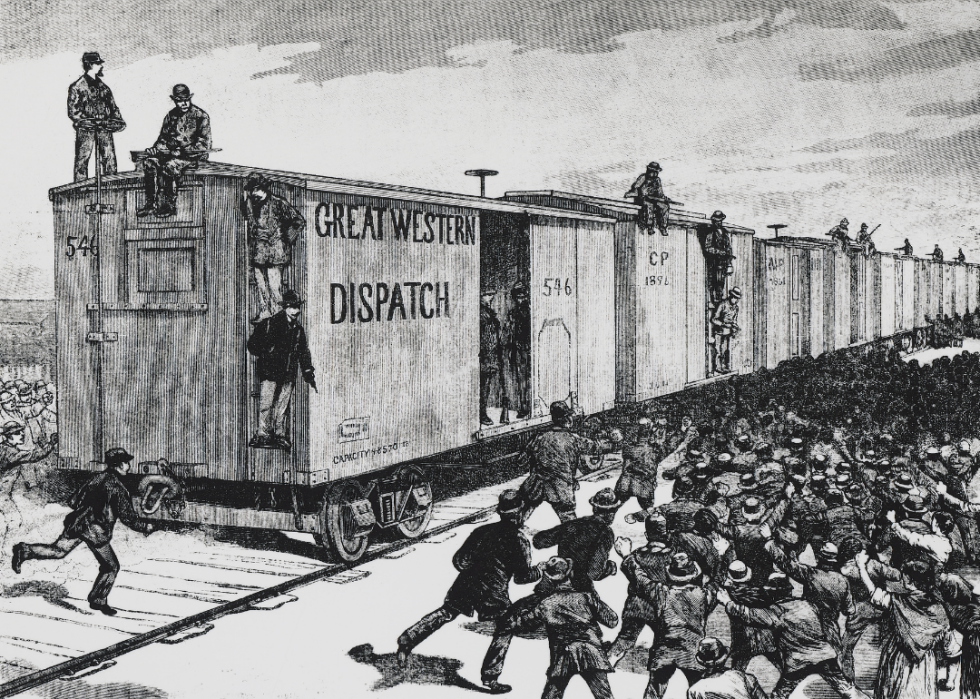

1886: Great Southwest railroad strike

In March 1886, a member of the Knights of Labor was fired from his railroad job in Texas for calling a company meeting, presumably without the approval of Texas Pacific. As a result, the Knights staged a full-on strike that quickly spanned Texas, Missouri, Kansas, and Arkansas to protest working conditions and demand an eight-hour workday. The multi-state strike continued over the course of two months and eventually led to violence.

Strikers burned railroad bridges in Texas, and conflicts between union members and law enforcement began to sprout up. The strike was unsuccessful however, and was called off when a congressional committee suggested the Knights of Labor end the strike. Internal friction within the Knights of Labor led to dwindling membership, and a new union—the American Federation of Labor—was formed.

1913: Paterson silk strike

A strike among textile workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1912—which developed when mill owners reacted to a new law that reduced the working hours and pay for women mill employees—was something of an archetype for the Paterson Silk Strike a year later. The 1913 strike among silk mill workers in Paterson, New Jersey, was to demand an eight-hour workday and various improvements to working conditions. Workers felt the conditions had been steadily fallen behind due to the ongoing technological advancements adopted by silk mills in Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island—developments Paterson mill owners were either unwilling or unable to keep pace with.

The strike lasted five months. Even though some 25,000 workers participated, the strike ultimately ended in failure, as the mill owners simply could not afford to meet the strikers’ demands, lest they go out of business. The largesse of the Industrial Workers of the World union swiftly degraded, and its influence in the eastern U.S. was permanently damaged.

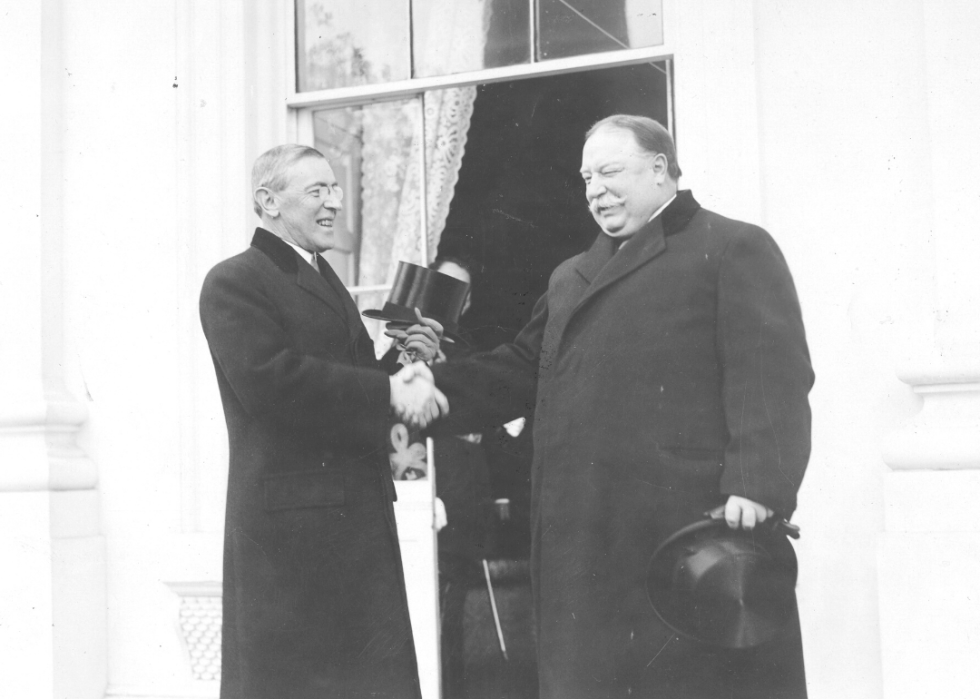

1913: President Taft creates Department of Labor

On his final day in office, just hours before Woodrow Wilson was to succeed him, President William Howard Taft inked an act that would lead to the creation of the U.S. Department of Labor.

Initially hesitant to sign the bill, Taft was given an ultimatum: Sign the act or allow it to run out when his term ended. The role of the Department of Labor was to implement the nation’s labor policies, which included the right for workers to have an eight-hour workday and bargain collectively. This latter attribute was in large part the result of the Department of Labor’s assuming responsibility for national war labor policies when the U.S. entered World War I in April 1917.

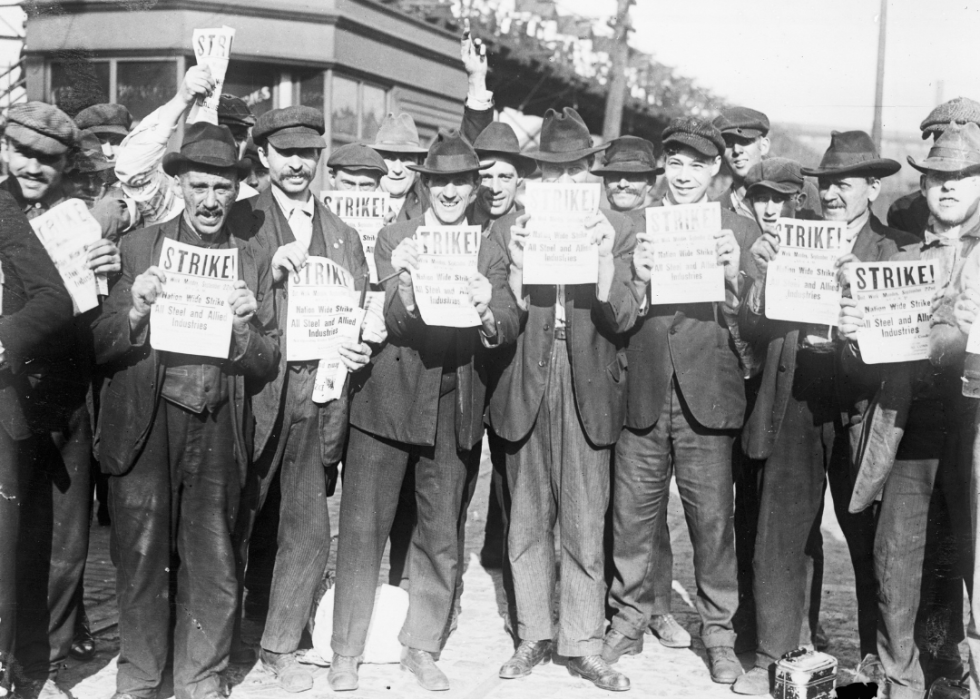

1919: A general strike stops the steel industry cold

The steel industry strike of 1919 occurred at a time when social tensions were at a fracture point following World War I, when the economic dependability of wartime production ended and inflation was on the rise, causing food prices to more than double. Steelworkers, largely in Pennsylvania and Ohio, had to deal with 12-hour workdays and racial- and class-based tensions at work. They wanted improved working conditions and higher pay—an uphill battle in the face of postwar inflation, which made it difficult for the steel companies to justify raising wages.

In September 1919, the entire steel industry came to a halt when 365,000 workers walked off their jobs. At the time, U.S. Steel—under the auspices of Andrew Carnegie, J.P. Morgan, and Charles Schwab—was the largest single employer in the country. Most of the strikers were white, and when the industry brought in Black strikebreakers, race- and class-fueled riots ensued. The strike eventually folded in January 1920 when many workers crossed the picket line because they could no longer afford to be out of work.

The steelworkers’ strike was one among many that occurred in 1919—along with strikes in the mining and law enforcement sectors, among others—and marked a crucial moment in American labor history. It served as an example of an industry breaking a long-term strike without recognizing any union—or involving the federal government.

1926: Passaic textile strike

The Passaic textile strike involved more than 15,000 wool, silk, and dye workers in the area of Passaic, New Jersey, who protested a 10% cut in their wages. Many of the workers were making little more than $1,000 annually—and even less for women. Mill managers knew a majority of the workers were immigrants from other nations and used that to prevent them from seeking union support, which subjected many workers to harsh working conditions and long hours at just about every textile mill in the region.

In August 1926, six months into the strike, workers elected a committee that met with officials from the United Textile Workers of America, where they would be recognized within the Local 1603 of the UTW. That November, the Passaic Worsted Company agreed to recognize the union, allow collective bargaining and arbitration of disputes, and agreed not to hire any new workers until all strikers were reemployed. Other mills soon followed suit, and the strike ended in March of the following year. Sadly, the mill owners later broke with their agreement, rehiring strikers at much lower wages.

1938: Fair Labor Standards Act is passed

The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 was created under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal program. It was legislation that had a significant impact on the U.S. labor market, establishing a minimum wage, “time-and-a-half” overtime pay, and a 44-hour workweek (later revised to a 40-hour workweek). This law also made it a requirement to compensate employees for working overtime and prohibited specific types of child labor.

The adoption of the 40-hour workweek was comparatively attractive against Sen. Hugo Black’s 1932 proposition of the adoption of a 30-hour workweek, which was met with fierce resistance. From October 1938 to June 1940, the Wage and Hour Division of the Department of Labor logged more than 43,000 complaints against companies for being in violation of the act.

1947: Portal-to-Portal Act is passed

The Portal-to-Portal Act was created to clarify the type of work time in which employees should be paid. The Supreme Court ruled that activities done solely for the employer count toward the workday. Essentially, as long as an employee is participating in activities that benefit the employer, the individual should be paid for his or her services—no matter where the work is performed.

However, certain key exceptions were clarified by the Portal-to-Portal Act that affected (and continue to affect) practically all workers, namely that workers are not compensated for the time it takes to commute to their job and any incidental activities that take place either before or after their work.

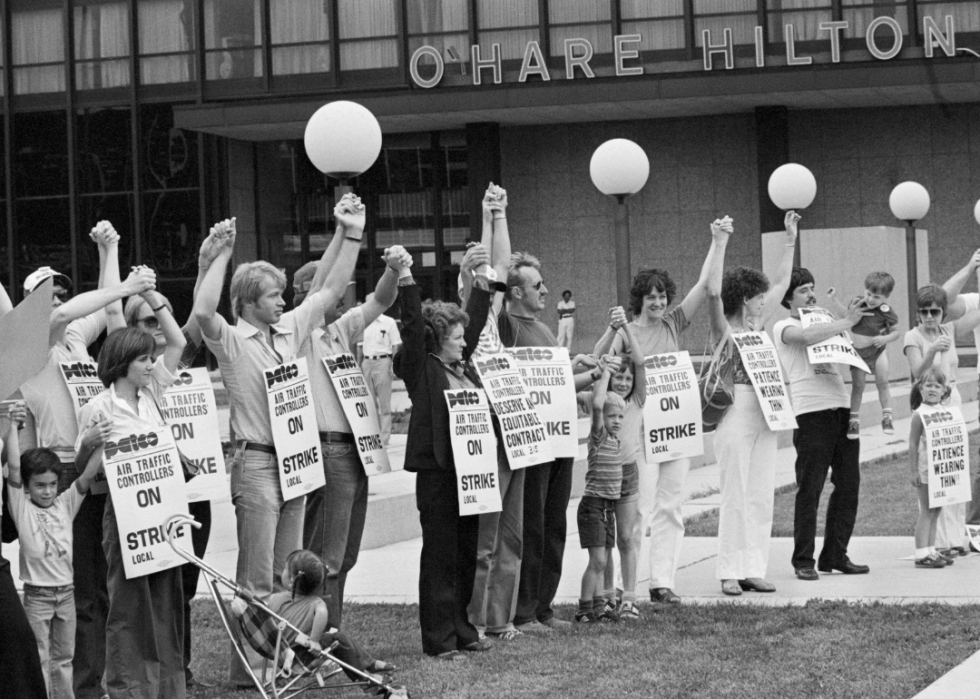

1981: 13,000 air traffic controllers walk off the job

In August 1981, two days after 13,000 air traffic controllers walked off the job, contract negotiations with the Federal Aviation Administration failed. Consequently, President Ronald Reagan fired more than 11,000 air traffic controllers who didn’t follow his orders to return to work. The mass firing banned the workers from federal service for life. Workers were demanding a four-day, 32-hour workweek and an across-the-board $10,000 salary increase.

Although this action slowed commercial travel, the system didn’t completely collapse. Airport workers filling other roles, along with some 2,000 nonstriking controllers, filled the gap left by the strikers, and national flight schedules largely returned to normal.

President Reagan stated the strike was illegal and imposed hefty fines against the air traffic controllers’ union, as allowed by a 1955 congressional ruling that was subsequently upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court. This demonstrated to businesses that negotiating with unions was not a default necessity and that the executive branch of the federal government could take a pro-business stance.

1985: Amendments to the Fair Labor Standards are passed

The Fair Labor Standards Amendments of 1985 allowed state and local governments to pay their employees’ overtime hours with paid time off from work instead of overtime pay. It further permits workers to accumulate paid time off hours and stipulates that all accumulated hours must be paid out to the worker in full should an employee leave their position. This bill also protects child employment standards and recordkeeping.

These amendments absolved government bodies from having to pay overtime as a wage, which, according to a statement of support issued by President Ronald Reagan, would save state and local governments $3 billion each year. The amendment was a counter-ruling to the Supreme Court and a measure of support to government entities, even while it restricted government workers’ rights to specific forms of compensation.

2022: California proposes 4-day workweek

In April 2022, California lawmakers proposed a statewide, four-day workweek to the legislature. The proposal would not only reduce the workweek from 40 to 32 hours per week for companies with 500-plus employees but also require employers to pay employees time-and-a-half if the employee worked more than 32 hours per week.

Cristina Garcia, a member of the California State Assembly, co-authored the bill in response to the COVID-19 pandemic impacting the nation’s seemingly obsolete work model. “We’ve had a five-day workweek since the Industrial Revolution,” Garcia told the Huffington Post. “I think the pandemic right now allows us the opportunity to rethink things, to reimagine things.”

However, the bill has been put on hold and has not advanced in the legislature as of May 2022. Nonetheless, some companies in the state are giving the idea a try, having noticed it has been successfully applied in other U.S. companies and parts of the country. Boulder County, Colorado, for example, fully adopted the shortened workweek in May 2021 after initiating a successful four-day workweek pilot during the first quarter of the year.