How Arizona hopes to avoid a 'nightmare' if November ballot stretches to a second page

This story was produced by Votebeat and reviewed and distributed by Stacker Media.

How Arizona hopes to avoid a 'nightmare' if November ballot stretches to a second page

Paper jams. Rejected ballots. Higher costs. Incorrect voter turnout numbers. All of these problems have happened in elections across the country when the ballot was so long that it stretched onto a second sheet of paper.

In Arizona, officials are worried about all of that and more, as they prepare to add an extra page to ballots for November's election, which includes the presidential race.

For most Arizona counties, it would be the first time in recent history that the ballot has enough contests to spill onto a second sheet. That's in large part because state lawmakers are expected to refer an unusually large number of measures to be decided by voters.

Election officials won't know for certain what's on the ballot until July or August, and the length will vary by county. But a second page is likely enough that they've already begun testing it, hoping that careful planning will help them avoid the problems second pages have caused elsewhere.

The directors are printing ballots and running them through tabulators two at a time, conducting mock elections, and updating one another in monthly meetings. Some are calling around to other states where multi-page ballots are commonly used to ask for advice.

Election administrators and voting experts from two of those states, Florida and Texas, told Votebeat that planning ahead and extensive testing are key.

There are also many decisions election administrators need to make before the election gets underway. Obvious ones include the amount of ballot paper and the number of voting booths and tabulators to order, all of which are affected by having a two-page ballot.

But election officials and lawmakers also must anticipate how to handle a wide range of potential problems and situations, and have procedures in place to resolve them.

For example, if two voters in the same household send back just the first page of both of their ballots in one envelope, should election officials count those ballots? How will they determine voter turnout, without being able to rely simply on the number of pages scanned by tabulators?

Mark Earley, supervisor of elections in Leon County, Florida, where multi-page ballots are common, called tracking turnout "a nightmare" when there is more than one page.

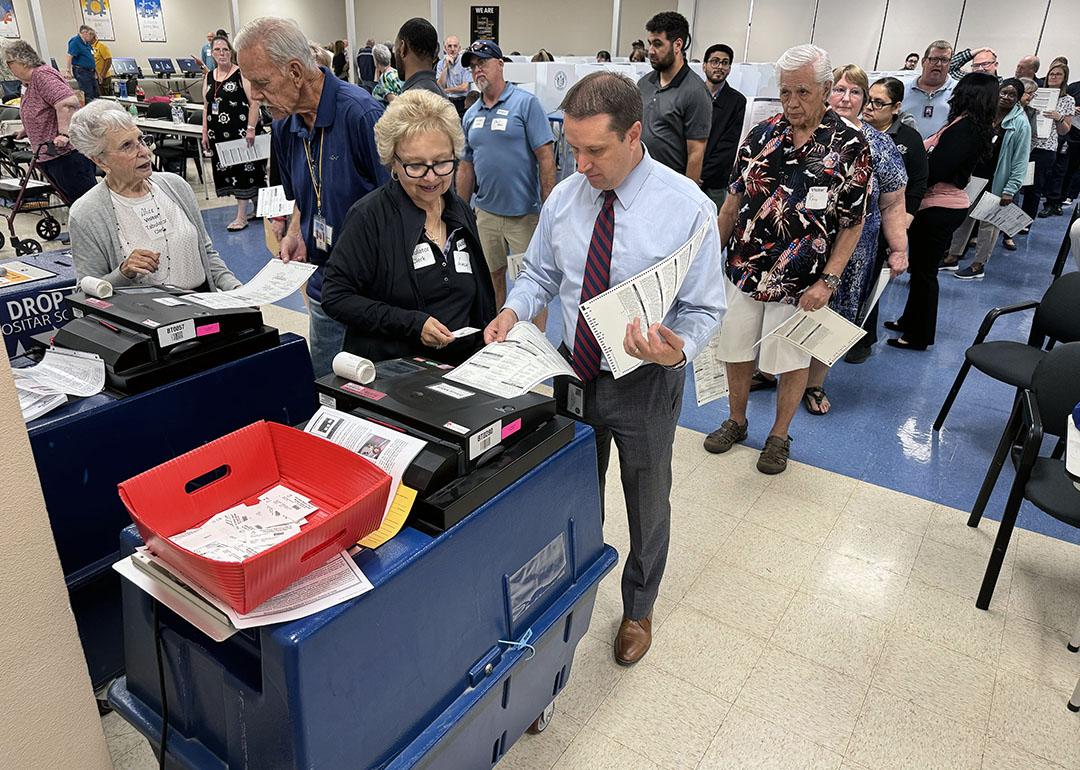

To help work through some of those potential problems, Maricopa County Elections Director Scott Jarrett on May 29 ran a mock election, pictured above, in which paid temporary workers got a quick training on how to handle a two-page ballot in a polling place, before facing a flood of fake voters. Election officials sometimes refer to these as two-card ballots.

Poll workers had many questions: How should they keep the pages straight as they sort stacks of ballots to hand to voters? What if the tabulator counts the first page of the ballot, but won't take the second? What if a voter is accidentally given two of the same page rather than both pages of the ballot?

Even as Arizona officials think these scenarios through, at least some are still hoping they won't need a two-page ballot. Pima County's deputy elections director, Jeremy George, said his county "will make every effort to keep it to one card." Yavapai County Elections Director Laurin Custis said she will "throw a small party if we don't have a two-card ballot."

"Deep down," said Coconino County Elections Director Eslir Musta, "I think we are thinking, 'Wouldn't it be great if it was a one-card ballot?'"

How ballots began to grow in Arizona

There are many reasons why Arizona has mostly been able to get away with one page, when other states haven't.

Under state law, the full text of wordy propositions can be moved off the real ballot to a separate pamphlet. State law also allows the text size to be smaller than recommended, and the ballot tabulators most counties use allow for 19-inch-long ballots.

In 2022, though, there were 10 statewide ballot propositions. Pinal County was forced to have two pages. Maricopa County managed with one page, front and back, albeit with very small type. This year, counties are expecting 15 or more propositions.

Arizona counties would have to spend more money on ballot paper, postage, and printer supplies if they switch to two pages. During the midterm election, Pinal County's printing costs increased by 28 cents per mailed ballot, and postage costs went from 80 cents for one page to $1.02 per ballot mailed.

Earley and another Florida administrator, Broward County Supervisor of Elections Joe Scott, said two-page ballots can also require more voting booths and tabulators, because voter mistakes on ballots and problems tabulating take longer to address when there is more than one page.

Scott also advised election officials to consider how they will handle different situations with mail ballots. Previously, in Broward, if a household sent in the first page of two different voters' ballots in the same ballot envelope, and the two ballots had identical votes on them, they would count one of the ballots and void the other. If the ballot choices weren't identical, they wouldn't count either one. But a new state law in Florida will now require all counties to reject both ballots in a situation like that, Scott said.

Scott said decisions like this should happen soon in Arizona, adding "it might already be too late" for statewide policies. For example, Jarrett said that, in this scenario, Maricopa County would reject both ballots. Custis said she is still debating these kinds of questions.

For his part, Musta said he has been calling other states to see if there are best practices, notably on calculating voter turnout. When ballots are a single page, election officials can rely on the number of pages scanned by tabulators to know how many people voted. With more than one page, it's not that simple. Some voters cast only the first page of the ballot, so officials can't just divide the number of scanned sheets by two to calculate turnout.

The last time Earley had a two-page ballot in an election, in 2012, 10,000 of 150,000 voters didn't return the second page.

The expected statewide recounts complicate the matter further. For various reasons, the two pages of the ballot may get separated during the initial count, and Musta said other states have told him not to worry about keeping the two pages together. But then decisions must be made about how results will be compared and reconciled.

The state's elections director is advising counties as they prepare to move to a two-card ballot, according to a spokesperson with the Secretary of State's Office. A spokesman for the office did not comment directly on whether it would issue any written guidance for counties on ordering supplies, testing, or how to address certain scenarios.

Two-page ballots create problems at the polls

A two-page ballot can mean double the wear on tabulation machines, and more maintenance issues.

"It's like two elections instead of one," Earley said.

When Pinal County deployed a two-page ballot during the 2022 midterm, the extra pages made it harder for poll workers to count the number of unused ballots during their end-of-night audits. That's partly why the county couldn't fully reconcile the election results.

Pinal County tabulates the ballots cast at polling places at a central counting facility, not on site at the polling place, and the sheer amount of paper meant it took workers much longer to count ballots on election night. As counting stretched into the early morning, workers made mistakes that wouldn't have been caught had it not been for a statewide recount later. That's in part because the poll worker numbers were so off.

Election officials across the state, such as Jarrett in Maricopa County and George in Pima County, say they are planning for the additional work and time that will go into counting a two-page ballot.

In Harris County, Texas, a two-page ballot during the 2022 midterm contributed to paper jams and errors when voters tried to cast their ballots, according to preliminary findings of a state investigation that studied a wide range of problems that occurred during the election.

"The paper jams led to many locations utilizing more ballot paper than anticipated, which may have further contributed to the supply issues related to ballot paper," the report found.

Bob Stein, a political science professor and election administration expert at Rice University in Texas, said that based on observation at polls and interviews with Harris County poll workers, his team found that some voters were putting both pages of the ballot into the tabulators at once, causing the jams.

He said anytime election officials introduce new processes, there's always a learning curve for voters and poll workers.

This is why testing and training are "absolutely critical," Stein said.

He also said any type of voter confusion, even if it just causes just a short delay for each person, will lengthen lines and increase wait times at the polling places.

In Maricopa County, 90 to 100 contests are expected on each ballot. It would be the first time since 2006 that the county has more than one page.

The mock election event on Wednesday was designed to see where these bottlenecks occurred. In the morning, during a drill that was meant to simulate an early voting day, a line formed after voters checked in, while they waited to get their ballot.

That's because it was no longer as simple as handing one page to one voter, and sorting the ballots coming off the printer was more difficult. It was also taking longer for poll workers to prefold the two pages of the ballots for voters, since during early voting they must place them in a ballot envelope instead of putting them into a tabulator.

Halfway through the experiment, a county trainer told the workers to change the way they were folding the ballots, to try to speed up the line. Jarrett said later that this kind of small adjustment could make a big difference.

After the mock event was over, Jarrett laughed when asked if anything came up that surprised him.

"Not yet," he said.