This story originally appeared on Better and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

History of the American mortgage

Homeownership has long been a part of the American Dream. Whether your generation, your grandparents’ generation, or your great-great-grandparents’ generation, most people equate the thought of owning a home with achieving the right type of success. After all, owning property can help you build wealth, give you access to equity, and offer something tangible to be passed down for generations.

Better, an online lender and homeownership platform with a free mortgage calculator, compiled a list of 15 events and milestones in the history of the American mortgage system, using information from news articles, encyclopedias, and historical literature.

While the idea of homeownership is hardly a new one, mortgages—the tool many people use to reach this major milestone—are a relatively recent concept. In fact, the option to borrow money to purchase a home has only been around for a couple of hundred years. And mortgages, as we know them, have been around for even less time than that.

The first real mortgage loans in America weren’t issued until the late 1700s, after the formation of the first commercial bank. By the late 1800s, banks and mortgage loans were common but still unlike the mortgage loans we see today. At that point in time, balloon payments were common and the mortgage loan terms offered by lenders were a lot shorter than you’d expect—making it tough for buyers to use them or even qualify.

The events that have occurred over the last 100 years have had an even bigger impact on shaping mortgage loans. The introduction of new laws, along with massive economic shifts—and other events, like questionable lending practices—have all played a part in refining the mortgage loan process. But what exactly are the events that have played a part in American mortgage loan history? And how have they helped shape mortgage loans to become what we know today?

Keep reading on to learn about the major historical landmarks of the American mortgage system.

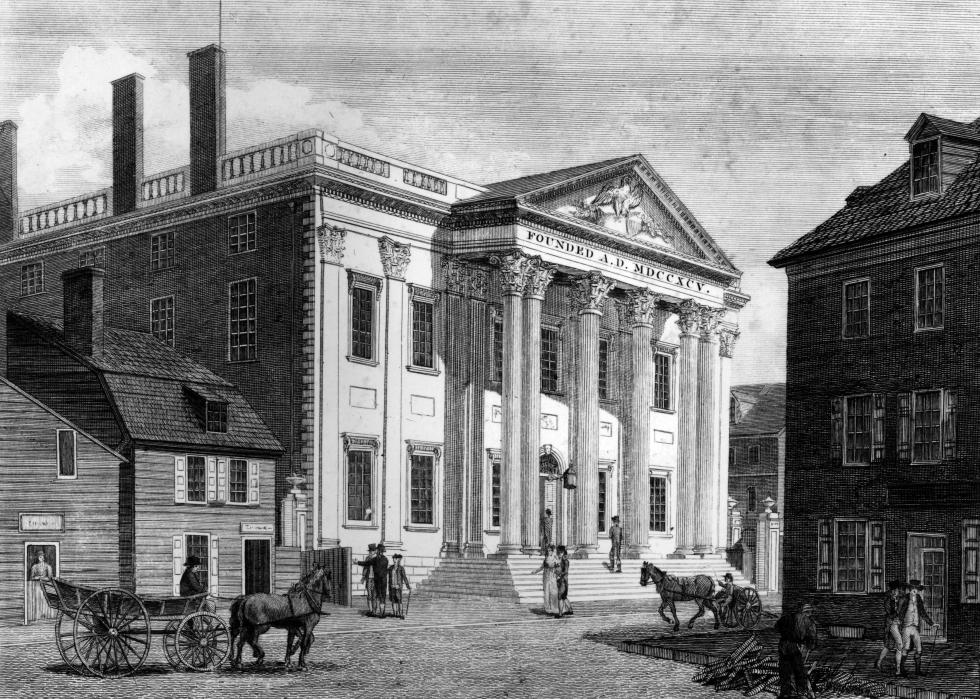

1782: First US commercial bank begins operations

The Bank of North America began operating on Jan. 7, 1782, in Philadelphia, becoming the first national and commercial bank in the nation. Unlike the banking institutions we have today, this bank was created by the Congress of the Confederation with the sole purpose of doing business with and for the government.

In its first year of operations, the Bank of North America had become a fully functional lender, offering stock shares of the bank and bank certificates, and had also issued a high volume of loans to the public and private sectors. The quick success of the Philadelphia banking institution led to the formation of commercial banks in other cities like Boston and New York just a few years later.

By the turn of the century, over a dozen cities across the nation had become home to newly formed commercial banks.

End of 1800s: Balloon mortgages become common

Waves of immigrants landed on America's shores in the late 1800s, causing a substantial increase in demand for property. In turn, there was an uptick in the demand for mortgages, but those mortgages were quite different from what they are today.

Five- and six-year amortization periods were the norm and borrowers typically had to put up half of the home’s purchase price upfront, as banks would generally finance just 50% of the property’s cost. Rather than requiring borrowers to make monthly payments on the principal they borrowed, banks only required borrowers to pay interest on the loan for the five-year period.

Once the loan term came to an end, borrowers were required to make a balloon payment for the full amount owed on the property. This raised the risk of loan default significantly and meant that borrowers typically had to have a substantial amount of money to buy a home.

1929: Great Depression causes housing mortgage crisis

Most people associate the 1920s with the stock market bubble and subsequent crash, but a housing bubble was also looming during that time.

It was more common than ever to finance the purchase of a home, and with more buyers in the market, real estate construction was booming. But balloon mortgages were still the norm at this point, and these loans’ affordable, interest-only payments led buyers to purchase homes they couldn’t afford. Many people were saddled with securities debt as well at this time, meaning they were overextended across the board. There were other issues, too, like land and home values lagging behind the growing mortgage debt, which helped to create the perfect storm for a housing crisis. And when the stock market crashed in a correction, that’s exactly what happened. The housing market bubble burst, causing major issues for homeowners and banks alike.

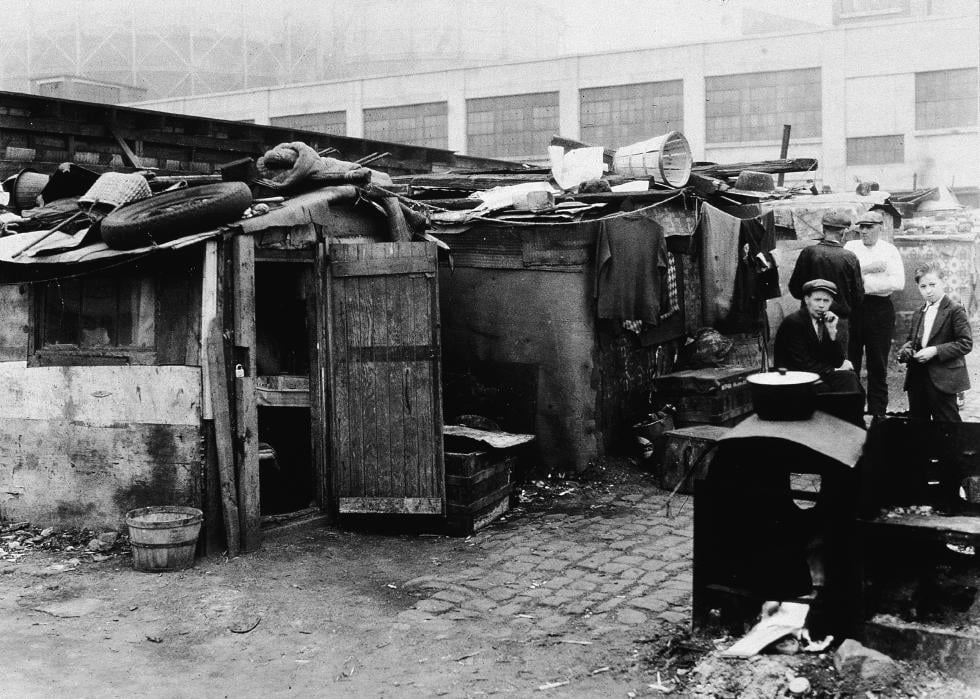

1933: 40-50% of mortgages are in default

By 1933, the bank failures that occurred due to the stock market and housing crash had affected the U.S. economy in a big way.

Business financing had all but disappeared, leading companies that were reliant on these money sources to fail en masse. Job losses were widespread and the unemployment rate had increased significantly. In turn, home prices plummeted and it became extremely difficult for struggling homeowners to sell their homes or properties to offload the expense. Mortgage and other bills went unpaid and millions of people were at risk of losing their homes to foreclosure. Due to heavy losses, however, foreclosure wasn’t always a viable solution for banks because of the lack of resources to fund the process.

1933: The New Deal transforms the American mortgage system

As part of the New Deal, the Home Owners’ Loan Act was signed into law in 1933 and had a massive impact on how mortgages were being handled. The goal of the Home Owners’ Loan Act was to “provide emergency relief with respect to home mortgage indebtedness, to refinance home mortgages, to extend relief to the owners occupied by them and who are unable to amortize their debt elsewhere.”

This act also marked the start of redlining, the process of color-coding maps to indicate where it was "safe" to insure mortgages—often leaving out predominantly Black neighborhoods. Furthermore, The Federal Housing Administration's "Underwriting Manual" advised highway installations as reasonable means to separate Black and white neighborhoods.

The Home Owners' Loan Act also required the formation of the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), which was in charge of providing relief to banking and financial institutions and Americans who were unable to afford their home-related costs. To provide this relief, the HOLC would acquire distressed mortgages and give the banks and other lienholders government-insured bonds in return. The homeowners, on the other hand, were issued new mortgage loans with significantly longer loan terms and lower interest rates, helping them to better afford the payments.

1934: Federal Housing Administration is created

In the mid-1930s, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) was created as a housing agency under the federal government. The goal of creating the FHA was to help make home financing more accessible and affordable while improving housing standards and driving employment opportunities in the housing construction industry.

This was extremely important after the Great Depression, as lenders were hesitant to offer low-interest loans to prospective buyers after the collapse of the economy a few years prior. To encourage more mortgage loans to be issued, the FHA insured the mortgage loans offered by banks and other lenders, thereby reducing the risk for the lenders. The FHA also introduced longer loan terms of 20 to 30 years and low down payment mortgage loans. This helped more buyers to enter the market and helped to greatly cut down on foreclosure rates by making home purchases more affordable for buyers.

1938: Fannie Mae added to National Housing Act

Fannie Mae in 1938 was added to the National Housing Act via an amendment to help further resolve the mortgage lending issues caused by the Great Depression. The government’s goal in creating Fannie Mae was to help stabilize the mortgage market by increasing liquidity for private lenders. To do this, Fannie Mae would buy FHA-backed loans from lenders to free up cash.

By doing this, lenders had more liquidity on hand and were able to offer more home loans to buyers. This helped to rapidly transform the mortgage lending industry for the better and had a huge impact on the housing market post-recession, too. Fannie Mae’s involvement in the mortgage lending space also led to the creation of the long-term, fixed-rate home loan, which made it easier for buyers to afford their home purchases.

1940-1960: Homeownership soars after World War II

Prior to World War II, there were significant declines in homeownership—especially farm home ownership—which was due in major part to the economic woes the nation had been facing. However, those trends were all but reversed following the war.

The passage of the Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944, known colloquially as the G.I. Bill, offered a range of benefits to veterans including low-interest mortgages—but largely left out Black service members returning from war. Coupled with the thriving national economy following World War II, the national rates of homeownership increased from 44% to 62% between 1940 and 1960. Even the states that had extremely low homeownership rates prior to World War II—Alabama, South Carolina, Louisiana, and Mississippi, among others—experienced a tremendous boom in homeownership.

To coincide with Veterans Day in November 2021, representatives James Clyburn of South Carolina and Seth Moulton of Massachusetts introduced the GI Bill Restoration Act which would grant descendants and surviving spouses of Black World War II veterans extended access to the VA Home Loan Guaranty Program and Post-911 GI Bill's education benefits.

1968: Fair Housing Act is passed to prohibit discrimination in the housing market

Civil rights were front and center during the late 1960s, and the focus on equal rights for all led President Lyndon Johnson to push legislation for fair housing to prohibit discrimination during the sale, rental, or financing of housing based on a person’s race, religion, national origin, sex, or other factors.

A fair housing bill was considered by Congress from 1966 to 1967, but ultimately stalled and was not passed. However, the push for fair housing laws continued—especially as Hispanic and African American veterans returned home from the Vietnam War and found they were unable to purchase or rent homes in certain areas due to discrimination.

When Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated in 1968, Congress quickly approved the Fair Housing Act following significant pressure from the public and the president. This meant people looking for housing could no longer be discriminated against due to their race or national origin. But while the act made discriminatory practices illegal, it has done little in the 50-plus years since to expand desegregation and increase fair housing opportunities.

1970: Freddie Mac is created to address expanding needs of homebuyers

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, mortgage loan interest rates were unpredictable and it was common for buyers to face unnecessary burdens while trying to obtain home financing. This made it tough for many buyers to fund their home purchases, especially at an affordable rate.

To help curb these issues, Congress created Freddie Mac to help stabilize the mortgage industry and make homeownership and rental opportunities more affordable. As with Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac achieves this by buying mortgage loans from lenders to free up cash and then packages them to be offered to investors. By doing this, lenders have more funds available for mortgage loans, which means that a wider pool of buyers gets access to the funding they need.

1970s: High interest rates and rising inflation affects new mortgage seekers

Unchecked inflation in the 1970s had a huge effect on mortgage loans as the Federal Reserve pushed interest rates higher and higher to compensate. This led to rates jumping from the mid-7% range in 1971 to more than 9% in 1974. The rates were pushed even higher over the next several years as inflation problems persisted, and mortgage lenders had to increase their rates to keep up.

By 1979, interest rates hit a whopping 11.20%, which made it incredibly difficult for mortgage seekers to afford a mortgage loan. With the dollar value low and interest rates high, potential homeowners were pushed out of the buying market throughout the 1970s—and well into the next decade.

1975: Home Mortgage Disclosure Act passes to improve unfair lending practices

There weren’t many safeguards in place prior to 1975 to ensure transparency in the lending process. While lenders were required to follow fair housing and other housing laws, there was nothing in place to monitor whether that was happening. That all changed when the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act was passed.

This act requires mortgage lenders to keep records of key pieces of lending practice information, which are then submitted to regulatory authorities so they can monitor trends in borrowing and lending. The goal of passing this act was to make mortgage lending more transparent while protecting borrowers and ensuring that lenders were following the letter of the law. It also allows regulators, public officials, and other interested parties to determine areas in which housing investments or government funding are needed.

Early 2000s: Subprime mortgage lending causes housing market to boom

During the early 2000s, mortgage lending took a turn for the worse as subprime mortgages became the norm. Prior to this point in time, it was difficult for buyers with poor credit histories or other financial barriers to acquiring a loan for a home. This changed when the demand for packaged mortgage loan-related investments—called the private-label securities market—grew.

Lenders needed to offer more loans to buyers to meet the investor demand for these types of securities, so they began offering risky loans to underqualified buyers instead. While many of these subprime loans appeared to be a good bet for buyers, these loans were designed to be unaffordable down the road. Still, this easy access to financing caused the housing market to boom, leading to high rates of homeownership and competition for available housing in many markets.

2007-2008: Housing bubble bursts, foreclosure soars

The subprime lending practices that were rampant in the early 2000s quickly led to a mess of foreclosures after the housing bubble burst. As of 2006, there were 717,522 homes in the U.S. with at least one foreclosure filing—or about 0.6% of all housing units. By 2008, that number had grown to 2,330,483—or about 1.8% of all housing units.

Florida and California were the two states hit hardest by the subprime mortgage crisis, but every state in the nation felt the effects of the bubble bursting. Lenders and banks felt the effects as well, with billions of dollars worth of losses during this time. These lender losses made it a lot harder for borrowers to qualify for purchase or refinance loans—and the rampant foreclosures caused housing prices to drop significantly.

2020-2021: COVID-19’s effect on mortgages and homeownership

The COVID-19 pandemic also had a massive effect on the mortgage and housing industry—and it’s due in major part to the decline in interest rates that occurred at the start of the pandemic. When the economy slowed to a halt in early 2020, the Federal Reserve dropped interest rates in a bid to stimulate spending. Mortgage rates fell in tandem, which led to a huge uptick in applications for refinancing and purchase loans.

Buyers who wanted to buy homes at record-low rates began snatching up available housing inventory—as did investors of all sizes, which led to high rates of homeownership. It also led to massive increases in home values and caused housing shortages across nearly every market in the nation, which priced out buyers who couldn’t afford the steep prices that came with the low rates.

Housing experts predict mortgage rates will rise in 2022, as the Federal Reserve is likely to increase interest rates multiple times throughout the year. The best advice for buyers is to research ahead of time and to be prepared to move quickly as soon as they see an attractive listing.