What America looked like during the Great Depression

What America looked like during the Great Depression

The Great Depression can be traced back to the devastating stock market crash of October 1929. Although the U.S. economy expanded exponentially in the period after World War I and the New York Stock Exchange surged, heedless speculation was all too common, putting many Americans at risk.

There were signs during the summer of 1929 that economic expansion was slowing. Consumer debt and unemployment rose, while wages remained low and production declined. In one week in October, tens of millions of shares were traded on the stock market as investors panicked, rendering millions of shares worthless. Investors who had borrowed money also saw their investments completely wiped out.

Financial stress continued to worsen from 1929 to 1933. U.S. industrial production declined by 47%, and unemployment is thought to have exceeded 20% at its peak. In comparison, during the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009, unemployment peaked at just under 10%. When President Franklin D. Roosevelt took office in 1933, he signed the New Deal into law, which created several programs aimed at spurring economic recovery and employing the jobless, like the Works Progress Administration and the Tennessee Valley Authority.

The American money supply also increased drastically, rising by almost 42% between 1933 and 1937, thanks to an influx of gold in the U.S., but also partly because of growing political tensions in Europe that precipitated World War II. Low interest rates also made credit more available and encouraged borrowing.

Stacker compiled a collection of 50 incredible images showcasing what life was like during the Great Depression. Using several historical and archival websites, the following slides help understand the stories behind the images, and how the Great Depression affected the lives of millions of Americans.

Read on for a glimpse into how Americans persevered during one of the most difficult decades in history.

Man sleeps on New York City docks in 1930 or 1931

A man wearing a three-piece suit under an overcoat is pictured in this photograph asleep in New York City, his attire indicating that he was once a white-collar worker. At the time when unemployment rates peaked during the Great Depression, one-third of the population of New York City was jobless. Many workers who kept their jobs were forced to take significant pay cuts. To jumpstart the economy in the city, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt commissioned the construction of the Lincoln Tunnel and the restoration of LaGuardia Airport.

[Pictured: A man sleeps on the docks in New York City photographed by Lewis Hine.]

Maxwell Street Market in Chicago around 1930

The Great Depression hit the city of Chicago hard because manufacturing was the dominating industry in the city, and it was this industry that was hit the hardest by the economic downturn. African Americans and Mexican Americans were disproportionately affected by the Great Depression—by 1932, up to 50% of Black workers in Chicago were unemployed. Even before the Great Depression, Chicago was facing financial difficulties. In 1928, the city was unable to collect taxes due to a property reassessment, which led to Chicago's fiscal emergency funds being completely emptied by 1932.

[Pictured: Maxwell Street market in Chicago circa 1930.]

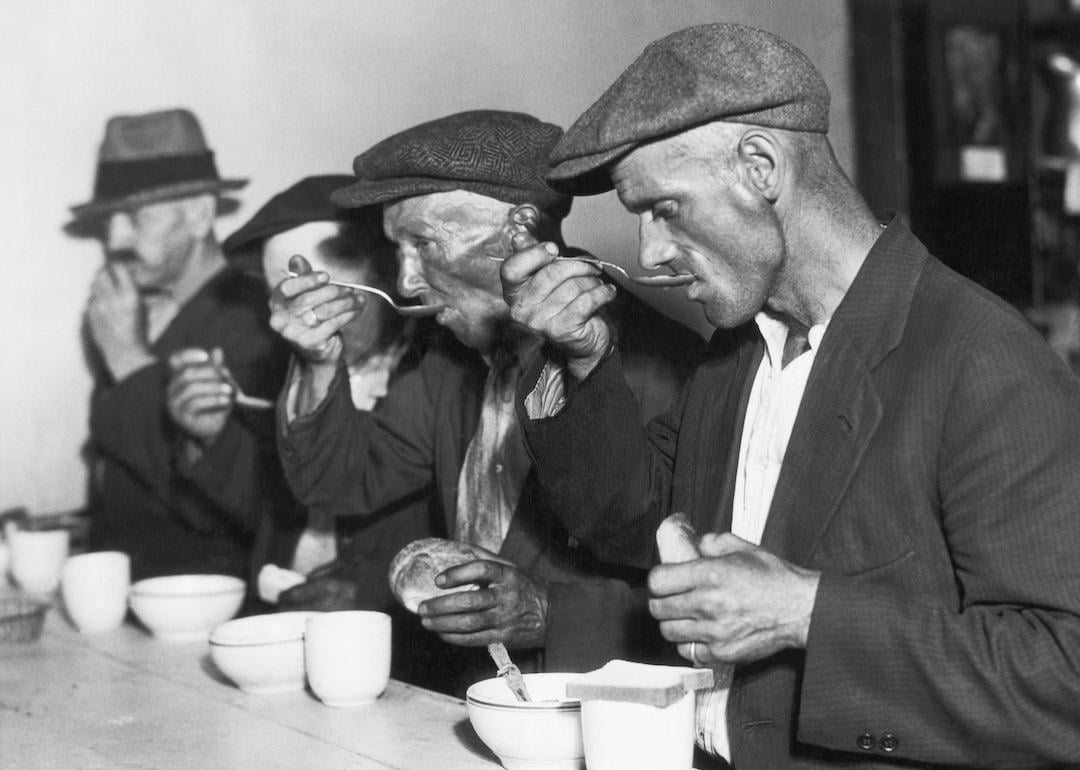

Unemployed people in line for dinner at a shelter in New York City in 1930

New York City's Municipal Lodging House opened in 1909 at 432 East 25th Street to provide accommodation and lodging to the homeless. The building had a total of 964 beds, and three meals a day were served there. In return, men had to work for five hours in a stoneyard. The Municipal Lodging House is thought to have been the first building constructed by the city to specifically serve temporarily homeless men and women. The demand for shelter at the building was so high that it was renovated in 1932 to lodge 4,500 people.

[Pictured: Throngs of unemployed waiting line to gain entrance to the Municipal Lodging House in New York City for the Sunday Dinner.]

A shanty town in New York in 1932

During the Great Depression, the demand for lodging in homeless shelters increased so dramatically that most cities simply couldn't accommodate everyone in need of housing. Instead, people experiencing homelessness constructed shanty towns or "Hoovervilles" close to free soup kitchens. These shanty towns usually consisted of tents or small shacks, with most people building temporary residences out of wooden crates, cardboard, scrap metal, or whatever other material they could find.

[Pictured: A shanty town in New York City.]

Line for a soup kitchen in Los Angeles in 1931

In this photograph, men wait in line at a soup kitchen that had just been opened by Aimee Semple McPherson-Hutton, an evangelist who had become an American cultural icon in the 1920s. She dedicated the Angelus Temple in 1923, which could hold up to 5,300 people. Throughout the Great Depression, the Angelus Temple provided food, clothing, and other necessities to families in need.

[Pictured: A soup kitchen in Los Angeles dated December 1931.]

Miners in Ward, West Virginia on strike in 1931

The West Virginia Mine Workers Union was created in 1931 in response to the difficult financial times many miners and their families faced during the Great Depression. Frank Keeney headed the union, and in July 1931, the union staged a major strike. Although a number of progressive labor organizations supported the strike, it was called off later in August as the cost of feeding and housing the striking workers became too expensive. The union later disbanded in 1933.

[Pictured: Striking miners in Ward, West Virginia, dated August 4, 1931.]

Menu at a penny restaurant in New York in 1931

While penny restaurants first came to be in the late 19th century, they rose to particular significance during the Great Depression. Bernarr Macfadden, who is credited as being one of the founders of American fitness culture, ran the most well-known penny restaurants in New York, using proceeds from his magazines to open several restaurants that would offer food staples like prunes and whole wheat bread for just a penny—Macfadden famously thought of white flour as poison. His penny restaurant on West 44th Street had four floors: one that offered fine dining, two where customers could eat at tables, and one where customers could stand and eat.

[Pictured: Menu of "Penny Restaurant" offering a measure of relief.]

Dormitory for the homeless in New York in 1930

Beginning in 1930, organizations like the Salvation Army amped up their operations as the economic downturn became more severe, and began offering more people free dinner and lodging. However, patrons of the Salvation Army usually had to listen to a sermon before they could eat dinner, and some people started avoiding the shelters because of the religious undertones. Instead, many people took to shanty towns or even slept in smoke shops.

[Pictured: A dormitory for homeless unemployed persons in New York City dated May 12, 1930.]

Signs depicting wage scales in 1935

Four years after the stock market crashed in 1929, about 25% of the U.S. workforce was unemployed. Even white collar professionals like doctors and lawyers experienced their incomes drop by as much as 40%. Although unemployment was all too common, the number of married women in the workforce actually rose during the Great Depression as families looked to add an extra wage-earner. However, many people criticized women for taking jobs while so many men struggled to find work of their own.

[Pictured: Signs showing depressed wage scales circa 1935.]

Unemployed workers protest in Chicago in 1932

In the early 1930s, Chicago's unemployment councils had 22,000 members while the Chicago Workers' Committee on Unemployment had 25,000 members in 1932. Chicago's unemployment councils would frequently hold protests to stop evictions. People would meet at Washington Park and then march over to the site of an eviction. These protests could draw thousands of people, and the march over from Washington Park would often attract even more onlookers. The protests were sometimes successful, with landlords and police deciding eviction wasn't worth the trouble.

[Pictured: A demonstration of 20,000 unemployed workers in Chicago's Grant Park dated Oct. 31, 1932.]

People protest an eviction in New York in 1933

In this photograph, protesters gathered as the New York City Marshal evicted four households from the "Paradise Alley" colony of artists and poets located at Avenue A and 11th Street on the Lower East Side in Manhattan. Those evicted included sculptor Jean Dellasser and artist Lee Hager. About 500 unemployed people protested the evictions and attempted to move the residents' furniture back into their homes. Police reserves were eventually called to break up riots.

[Pictured: An eviction protest in New York City dated Jan. 11, 1933.]

Children take apart packing boxes for stove fuel in New York City in 1931

During the Great Depression, children often worked both inside and outside the home: babysitting, cleaning houses, shining shoes, delivering papers, and picking crops. But the overall lack of jobs actually led to children and teenagers staying in school for longer than ever before, and high school became a normal teenage rite of passage for the first time. A record-breaking 65% of teenagers attended high school in 1936.

[Pictured: Youth chopping packing boxes for kitchen stove fuel in New York City.]

Farmers in Iowa attempt to stop a foreclosure sale in 1935

In the early years of the Great Depression when a farm was foreclosed on in Iowa, farmers and neighbors would frequently attend foreclosure auctions to intimidate potential buyers in the hopes that the farm equipment could be purchased for a low price and returned to its owners. Nevertheless, between 1930 and 1935, about 750,000 farms disappeared through foreclosure or bankruptcy sales.

[Pictured: A foreclosure sale in Iowa in the early 1930s.]

Family listening to the radio in Michigan in 1930

As the Great Depression affected more and more American families, at the same time, the amount of time people spent listening to the radio increased, as the radio provided a low-cost escape from financial hardships as well as a way to keep up with the news. After he was sworn in in 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt began broadcasting his Fireside Chats, in which he sought to inform the public of his programs and current events.

[Pictured: A rural Michigan family listens to their radio in August 1930.]

'Hunger Marchers' protest in Boston in 1932

In this photograph, 500 "hunger marchers" descended on Boston Common to encourage the state's government to support relief measures, including unemployment insurance. Hunger marches originated in the United Kingdom in the 20th century but became widespread in the United States during the Great Depression as the unemployed grew increasingly frustrated with the economic, political, and social norms of the time. In Massachusetts, these protests often happened on either the Boston Common or near the State House.

[Pictured: "Hunger Marchers" protest on Boston Common on May 2, 1932.]

Minnesota farmers in St. Paul protest lack of government relief in 1933

Minnesota's Farmers' Holiday Association was founded in 1932 to urge farmers to partake in a buying and selling "holiday," in which farmers would refuse to buy and sell goods or pay taxes until they were paid a fair rate for their labor. In March 1933, 20,000 Minnesota farmers marched to the state's capital of St. Paul in support of pro-farm legislation. But later that year, the group's attempts at a nationwide strike fell apart when dairy farmers and corn farmers couldn't agree on tactics.

[Pictured: Minnesota farmers protest march in St. Paul on March 22, 1933.]

Signs urge veterans against voting for certain candidates in 1932

Congress passed legislation in 1926 to give veterans of World War I bonuses based on the length of their service in 20 years. While veterans were allowed to borrow against their bonuses, banks simply had no credit to spare during the Great Depression, and in 1932, several veterans organized the Bonus Expeditionary Forces to demand an early payout of their bonuses. Between 20,000 and 40,000 veterans traveled to Washington D.C., occupied buildings, and set up shantytowns to make the case in person for their bonuses.

[Pictured: The "Bonus Expeditionary Forces" urge voters not to vote for Hoover and several other candidates in St. Paul, Minnesota in 1932.]

Ford owner signals support for Roosevelt prior to 1932 election

Automobile magnate Henry Ford endorsed incumbent President Herbert Hoover in the 1932 election for president in June of that year, calling him best-fitted for the job compared to any of the other candidates in either political party. After a rumor circulated that Ford had encouraged his employees to vote for Hoover, Jerome T. Harriman, who represented traveling showmen in the U.S., announced he would start a movement to contradict Ford's endorsement and said he would send a bumper sticker to any Ford owner who supported Roosevelt in the election.

[Pictured: Jerome T. Harriman points to a sticker on his car supporting Roosevelt for President dated Oct. 20, 1932.]

Men enjoy beer on 4th of July in Bangor, Maine in 1933

Although alcohol was illegal during the Great Depression, the economic downturn ignited a movement of people seeking to repeal Prohibition and the 18th amendment that made alcohol illegal. Those who opposed Prohibition argued that the U.S. would benefit from the tax revenue and jobs that legalization of alcohol would provide. It was estimated that Prohibition resulted in the loss of 250,000 jobs and $11 billion in alcohol-related taxes. In 1933, Prohibition was finally reversed.

[Pictured: People celebrate the first 4th of July after Prohibition Repeal in Maine.]

Workers unload crates of beer after the repeal of Prohibition in 1933

President Franklin D. Roosevelt campaigned in the 1932 election on repealing Prohibition, claiming that it would raise the federal revenue by several hundred million dollars per year in the midst of the Great Depression. Roosevelt was elected, and in February of the following year, Congress passed the 21st amendment, which repealed Prohibition. The amendment required state legislatures to ratify it, and nine months later, Utah became the final state needed to approve the amendment.

[Pictured: Workmen unloading crates of beer stacked at a New York brewery in 1933.]

Workers at the U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing in 1933

Roosevelt signed the Emergency Banking Act into law in 1933, which gave the president, the comptroller of the currency, and the Secretary of the Treasury more control over the country's banking system and was intended to restore trust in the financial system. The law also gave the Federal Reserve the power to issue emergency currency backed up by the assets of a commercial bank to increase the money supply.

[Pictured: Workers at the U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing in Washington D.C. cut dollar bills from newly printed sheets in March 1933.]

Customers in New Jersey after a shuttered bank was granted deposit insurance in 1936

D'Auria Bank and Trust Company in Newark, New Jersey, closed in 1936, and several of the bank's officers and directors were arrested for making false statements in violation of the Federal Reserve Act in order to receive deposit insurance. However, this did not affect the payout for deposits from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., which insured deposits up to $5,000 for the bank's more than 3,000 customers.

[Pictured: FDIC bank insurance saves depositors in Newark, New Jersey.]

Roosevelt visits a CCC camp in Virginia in 1933

The Civilian Conservation Corps was a work relief program that began as part of Roosevelt's package of New Deal programs to reinvigorate the U.S. economy. The CCC provided jobs on environmental projects to millions of young men, and the organization planted more than three billion trees and built trails and shelters in more than 800 parks during its nine years in operation. Just months after Roosevelt established the CCC in 1933, there were 1,433 established working camps and 300,000 employees.

[Pictured: President Roosevelt visits CCC Camp #350 in Virginia's Shenandoah Valley in August 1935.]

An automobile assembly line in Detroit in 1934

In the first decades of the 1900s, Detroit was the automobile capital of the world, and by 1914, the city was producing half of the cars in the world. However, when the stock market crashed in 1929, just a year later auto sales declined by 75% and as a result, thousands of people lost their jobs. In 1933, Frank Couzens became mayor of Detroit and helped revive the city's economy by balancing the budget, acquiring federal relief funds, and paying public employees with "I.O.U.s."

[Pictured: Workers on a busy assembly line in a Detroit automotive factory.]

Construction of the Golden Gate Bridge in 1935

Construction on San Francisco's Golden Gate Bridge began in 1933, and despite the treacherous conditions and the bridge's location over open water, people scrambled for jobs on the construction crew, which comprised many people with no building experience desperate for a job with steady wages. The bridge's two towers were completed in 1935, and the bridge finally opened to the public in May 1937.

[Pictured: Construction on the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco dated Sept. 20, 1935.]

A dust storm in Springfield, Colorado in 1937

In the 1930s, the midwestern United States experienced the worst drought in North America in a thousand years, which was made worse by unsustainable farming practices. High winds at the time blew away topsoil, which was no longer protected by prairie grasses that had been farmed away. By 1937, more than one out of every five farmers was receiving federal emergency aid, and many became homeless or were forced to migrate to find work.

[Pictured: A dust storm in Colorado in May 1937.]

Workers clear flood debris in Kentucky in 1937

One of the most severe floods in American history plagued the Ohio River Valley in 1937, which particularly devastated Louisville, Kentucky and southern Indiana. Two-thirds of the population of Louisville had to be evacuated, and an estimated 60% of the city was flooded. The recovery and cleanup took months, even with the help of the military and aid workers, and several of Louisville's neighborhoods completely disappeared.

[Pictured: A WPA truck being loaded with flood debris in Louisville, Kentucky in 1937.]

A general store in Moundville, Alabama in 1936

This photograph was captured by Walker Evans, one of the most prominent photographers who documented the Great Depression and its impact on Americans. In 1935, Evans took a job with the Department of the Interior to photograph jobless coal miners in West Virginia. He later became an information specialist with the Farm Security Administration, which was created by the New Deal. His photos captured American life, from barbershops to churches in rural areas, and first appeared in print in the late 1930s.

[Pictured: The interior of a general store in Moundville, Alabama as captured by FSA photographer Walker Evans in 1936.]

Farmers in Oklahoma in 1936

Dorothea Lange, who took this photograph, began working with the California State Emergency Relief Administration in 1935, which had begun a photo-documentary project to document the rural poor. Lange traveled around California, the south, and the southwest between 1935 and 1939 and captured the life of rural and migrant farmers. She is most well known for her "Migrant Mother" photograph, which was published in The San Francisco News in 1936.

[Pictured: Farmers in Oklahoma by FSA photographer Dorothea Lange in August 1936.]

A teenage sharecropper in Georgia in 1937

Sharecropping refers to the agricultural practice in which people cultivate and farmland that they typically rented from a landowner who would receive a portion of the crop. After the Civil War, sharecropping and tenant farming was a common occupation for African Americans and poor whites. Tenant farming peaked during the Great Depression, in which tenant farmers comprised 65% of all farmers in Alabama, but declined significantly with the onset of World War II.

[Pictured: FSA photographer Dorothea Lange portrait of a teenage sharecropper in Georgia.]

Homeless people ride freight train to California in 1934

"Hobos," or unemployed people experiencing homelessness, would sometimes hop on a freight train to travel somewhere else to look for work. However, this was a very dangerous practice as it involved running alongside a freight train as it gained speed and then jumping into an open boxcar. Many were killed or injured just attempting to hop on a train, and railroads also hired "bulls" to arrest or intimidate anyone who wasn't a paying customer.

[Pictured: People ride empty freight cars to Southern California in 1934.]

An abandoned farmhouse in central Oregon in 1936

Oregon experienced a severe drought beginning in 1928, which didn't let up until more than 10 years later in 1940. The effects of the drought were worsened by already-declining prices for wheat and other crops, and some of the government's relief efforts weren't welcomed by Oregonians. The Taylor Grazing Act attempted to restore grazing land by limiting herders' access to the land, but that put many small farmers and farming operations out of business.

[Pictured: An abandoned farmhouse in central Oregon as captured by FSA photographer Arthur Rothstein in June 1936.]

Street musicians in West Memphis, Arkansas in 1935

Jazz and swing music were the most popular music genres during the Great Depression, and people often listened to artists that included Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, and Tommy Dorsey. Country music also became popular, with Woody Guthrie ushering in the rise of country and folk music. Guthrie toured the country and penned a number of songs in support of the labor union movement.

[Pictured: Two street musicians in West Memphis, Arkansas photographed by Walker Evans in 1935.]

A roadside food stand in Louisiana in 1936

With the Great Depression, cheap, commercially processed food increased in popularity, while the interest in gourmet cuisine at fancy restaurants dwindled. Almost every medium-sized city in the United States had a roadside hamburger stand, and thousands fast food restaurants were built in downtown urban areas, leading to the first real popular American fast-food chains. Several processed food products that came to be during the Great Depression are still popular today, like Fritos and Kraft macaroni and cheese.

[Pictured: FSA photographer Walker Evans documents a roadside food stand in Ponchatoula, Louisiana in 1936.]

Construction of Hoover Dam in 1935

In 1928, then-U.S. President Calvin Coolidge signed legislation approving what they called the Boulder Canyon Dam Project, which would later become the Hoover Dam. Work toward the dam stretched over three presidencies—President Herbert Hoover signed the first appropriations bill for the dam in 1930, and when construction started on the project, it was announced that it would be renamed to the Hoover Dam. Today, the Hoover Dam stores enough water to irrigate 2 million acres, and generates enough hydroelectric power for 1.3 million people annually.

[Pictured: WPA Construction of the Boulder (Hoover) Dam in 1935.]

Laborers take the Tennessee Valley Authority exam in 1933

The Tennessee Valley Authority was authorized in 1933 as part of Roosevelt's New Deal in order to help the Tennessee Valley region recover from the financial hardships of the Great Depression and improve the general quality of life in the area. The TVA was unique in that it was essentially a "corporation" backed by the federal government. The organization, which is still in operation today, has supplied electricity and spearheaded one of the largest hydropower construction projects to take place in the U.S.

[Pictured: Men take the TVA Examination in Clinton, Tennessee.]

WPA airport workers strike in Philadelphia in 1936

In 1935, the mayor of Philadelphia approved a Works Progress Administration project to improve the city's airport, which was then called the Philadelphia Municipal Airport. The WPA, which was enacted by Congress in 1935 as part of the New Deal and provided jobs on construction projects to thousands of unemployed men, modernized the airport and added a new terminal, renaming the airport to the S.D. Wilson Airport. It would later become the Philadelphia International Airport.

[Pictured: WPA workers strike at the Municipal Airport in Philadelphia on Aug. 6, 1936.]

Vernon Evans stands next to his car in Montana in 1936

Vernon Evans was working in Lemmon, South Dakota, as a hired hand during the onset of the Great Depression, and was soon laid off. He and his wife Flora, along with her sister and brother and another friend, packed up and set off for Oregon, with only $54 between them. On the way, their car captured the attention of FSA photographer Arthur Rothstein, who took this iconic photo of Evans standing next to his Model-T in Missoula. Evans lived in Oregon for nine years until his father died, upon which he returned home to South Dakota.

[Pictured: Vernon Evans photographed by FSA photographer Arthur Rothstein near Missoula, Montana in 1936.]

Eroded farmland in Martin County, Indiana in 1938

In the period following World War I, farmers responded to incentives from the federal government to provide food for countries in Europe that were recovering from the war, and over-plowed and over-planted their land, resulting in catastrophic erosion, mounting debts, and crashing prices for agricultural goods during the Great Depression. The combination of this erosion and a severe drought created the Dust Bowl, which severely impacted 27 states and affected more than 75% of the U.S. as of 1934.

[Pictured: Eroded farmland in Martin County, Indiana dated May 1938.]

A church in Natchitoches, Louisiana in 1940

The Great Depression caused a religious reckoning for some in the United States: many took to church and religion to pray for economic recovery and revival, as well as rain in drought-affected areas, while others were faced with disappointment and despair that caused them to turn away from religion. When the New Deal was enacted, it raised questions about what responsibility the church and religion still had for social welfare and brought about some discontentment. At the same time, Jewish Americans and Catholics were increasingly paying more attention and expressing more concern about religious persecution in Europe.

[Pictured: A small church in Natchitoches, Louisiana in June 1940.]

Evicted sharecroppers with their possessions in Missouri in 1939

The Southern Tenant Farmers Union was founded in 1935 by sharecroppers to achieve government relief, after New Deal agricultural policies did not bring them the economic benefit they had hoped. In late August 1935, thousands of sharecroppers went on strike, and although landowners eventually raised wages, tensions between farmers and landowners only continued to grow and even became violent. By 1936, the organization had more than 25,000 members.

[Pictured: A portrait of evicted sharecroppers and their possessions in New Madrid, Missouri as photographed by Arthur Rothstein.]

Family in Oklahoma leaves home following drought in June 1938

In this photo by Dorothea Lange, a family in Pittsburg County, Oklahoma, is leaving their home due to a severe drought in the region during the summer of 1938. Beginning in 1930, the Midwestern region of the United States was hit with a drought that transformed the Great Plains into a desert that came to be called the Dust Bowl. The panhandle of Oklahoma was most affected by the drought, which lasted about a decade.

Children of migratory bean-pickers in Oregon in 1939

Many Americans from the Midwest who were affected by the Dust Bowl migrated west to look for work, aided by Route 66, which led to the west coast. But upon arriving in the west, many migrants found that there were fewer employment opportunities than they had hoped for and to make matters worse, a significant reduction in the going wage rate. Many of the midwestern migrants set up camps in irrigation ditches in farmers' fields, which had poor sanitary and living conditions.

[Pictured: Children of migratory bean farmers in Oregon from Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, California, and Missouri as photographed by Dorothea Lange in 1939.]

People wait in line for food at a relief program in San Antonio in 1939

San Antonio was hit particularly hard by the Great Depression because of the city's historical skepticism to unionized labor and heavy industry. For example, even during the peak of unemployment during the Great Depression, San Antonio rejected Ford Motor Company's interest in building a production facility in Bexar County, where San Antonio is located. And while San Antonio had historically been a military city, it was heavily affected by the downsizing of the military following World War II.

[Pictured: People wait in line to receive commodities through a relief program in San Antonio, Texas in March 1939.]

Workers install telephone lines in a rural area

The Rural Electrification Administration was founded by Roosevelt in 1935 with the aim of bringing electricity to rural areas of the U.S. In the 1930s, 90% of people living in urban areas had electricity, compared to only 10% of people living in rural areas. Private electrical companies largely ignored rural areas, assuming farmers wouldn't be able to afford electricity and not wanting to spend large sums of money to install electricity lines. By 1939, the REA helped create 417 local electricity cooperative companies and brought electricity to 25% of rural households.

[Pictured: REA workers install telephone lines in rural areas.]

A railroad station in Fargo, North Dakota in 1939

The railroad industry was already suffering heading into the Great Depression, having been affected by government regulation, the increasing popularity of automobiles, and investment in competing modes of transportation. Locomotive sales dropped drastically, and a third of the nation's railroads went into bankruptcy during the Great Depression. However, efforts through the New Deal did help to finance the electrification of the Pennsylvania Railroad from New York City to Washington D.C.

[Pictured: FSA photographer Arthur Rothstein captures the scene at a train station in Fargo, North Dakota in 1939.]

A worker in the Social Security Administration in 1937

Roosevelt created the Social Security Administration when he signed the Social Security Act into law in 1935 to create a federal safety net for the unemployed, elderly, and disabled. Inspired by some of the economic benefits offered in Europe, Roosevelt created a system in which people contributed to their own financial security by contributing part of their wages through payroll tax reduction. Registration for social security opened one year later in 1936.

[Pictured: A worker in the new Social Security Administration inputs data.]

Food market display of signs welcoming the use of food stamps

Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace created the first food stamp program, which was implemented in 1939 as part of the New Deal program. Low-income families could purchase food stamps and additional bonus stamps for food items that were in surplus. Orange stamps would buy food and household items, while blue stamps were used to purchase commodity surplus goods, which could include things like beans, flour, or eggs.

[Pictured: A market sign welcoming food stamps made available to Americans in 1939.]

Migrant worker passes sign advertising Navy recruitment

Although the Great Depression slowed the growth of the U.S. Navy, especially research and development programs, several advances were made in aviation technology. As the 1940s approached and war seemed to be on the horizon, the Navy expanded its pilot training program and started designing new modern ships and airplanes. Even though the U.S. proclaimed neutrality when World War II began, the Navy's fleet would patrol the seas long before the U.S. officially got involved.

[Pictured: A migrant worker from Arkansas walking past a poster advertising recruitment for the U.S. Navy in Benton Harbor, Michigan, photographed by John Vachon in 1940.]

Mural promoting the sale of defense bonds in Grand Central Station

To finance its involvement in World War II, the U.S. promoted war bonds, which were ways Americans could invest money by lending it to the government. During the entirety of World War II, 85 million Americans bought bonds worth a total of more than $180 billion. The government even successfully kept inflation down during the war by convincing the public that it was their patriotic duty to buy war bonds.

[Pictured: A mural promoting the sales of defense bonds in New York's Grand Central terminal photographed in 1941.]