This story originally appeared on GigaCalculator and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

So sweet: How added sugar is skewing US nutrition

Any consumer who peruses a food product's nutrition label before making their purchase decision is all too aware of how prevalent added sugars are—even in many household staple items, such as bread and cereal products. The Food and Drug Administration defines added sugars as "sugars that are added during the processing of foods (such as sucrose or dextrose), foods packaged as sweeteners (such as table sugar), sugars from syrups and honey, and sugars from concentrated fruit or vegetable juices."

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that Americans 2 years and older limit their consumption of added sugars to less than 10% of their total daily calories. That translates to 200 calories or less from added sugars for a diet of 2,000 calories per day. For children younger than 2, the recommendation is even stricter—no foods or drinks with added sugars at all.

Added sugars contribute to all manner of health concerns, chief among them obesity, which remains an urgent problem in the United States. About 32% of American adults and 15.5% of adolescents experience obesity, according to CDC data as of 2020. Adults who have obesity are at greater risk for a range of serious health problems, including heart disease, stroke, Type 2 diabetes, some cancers, and poor mental health. People with obesity also have a greater chance of developing severe COVID-19 symptoms.

To gauge the impact of added sugar on the national diet, GigaCalculator investigated how added sugar is skewing U.S. nutrition using data from the Department of Agriculture and various government and scientific sources.

How added sugars got their own line on nutrition labels

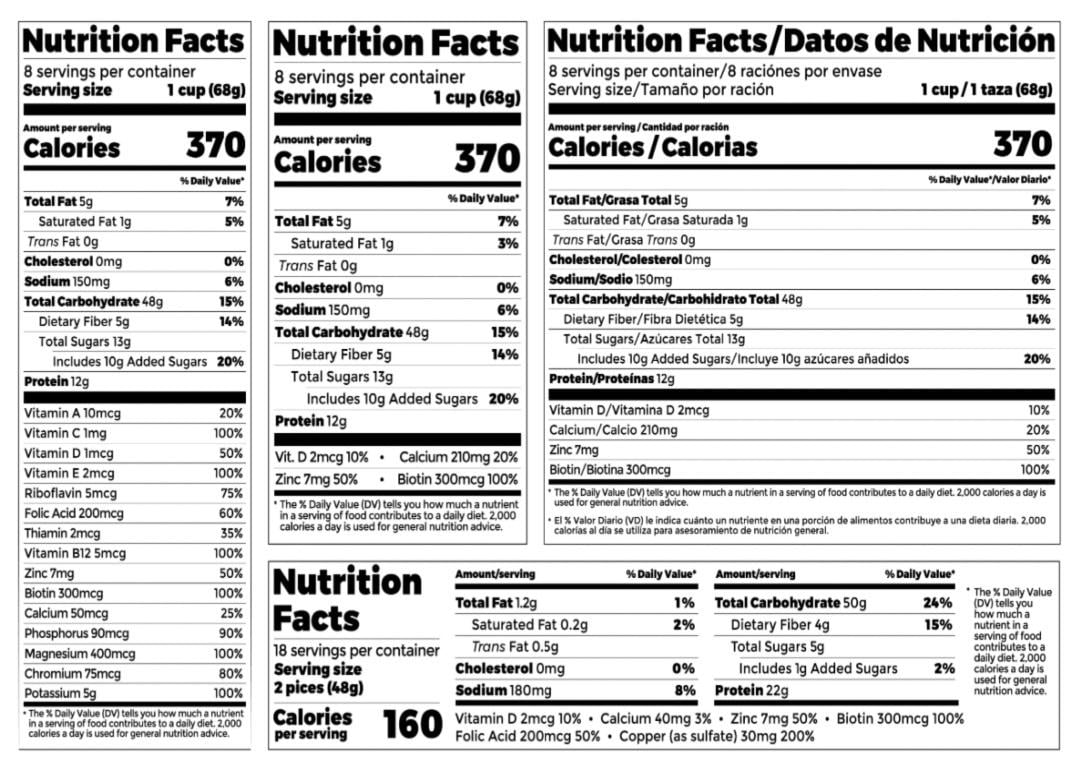

Added sugars were first listed on nutrition labels in 2020, though the change was announced in 2016 partly because of the nutrition campaigns spurred by former first lady Michelle Obama. The sugar industry has a strong lobbying arm, and the changes to the FDA's requirements for nutrition labels were met with significant resistance, notably from the soda industry. One of the main reasons the label updates were given four years to go into effect was the tremendous cost associated with the new requirements; it will ultimately cost an estimated $2 billion to change all the product labels at all points of sale nationwide.

The FDA reasons that disclosing added sugars on the nutrition facts label of every product not only allows Americans to see how many grams there are in a portion of food and what percentage of total calories they constitute but also empowers them to use that information to make healthy food choices. An exception is made for single-ingredient sugars such as table sugars, maple syrup, and honey. Most Americans get their added sugars from beverages, desserts, and sweets.

While there is no daily recommendation for how much natural sugar—naturally present in milk, fruits, and vegetables—should be in a person's diet, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommends that added sugars make up less than 50 grams of added sugars on a 2,000-calorie daily diet.

The amount of added sugars per capita in the US climbed steadily until 1999

In the U.S., total caloric sweeteners available for consumption peaked at 153.6 pounds per capita in 1999. This was quite a jump from 1969's 117.9 pounds per capita. During that period, the U.S. population increased by more than 76 million people, meaning sugar consumption, and thus the viability of the sugar and sweetener industry, grew much more robust.

When total caloric sweeteners peaked in 1999, health groups petitioned the FDA to recommend that Americans limit the amount of sugar consumed daily. In a paper published the following year, USDA researchers noted that Americans who consumed more added sugars—more than 18% of their overall caloric intake—also typically consumed more calories but fewer nutrients. They drank 15 times more soft drinks and "fruitades" (e.g., lemonade) each day.

Researchers at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, traced today's problems with obesity to baby formula in the 1970s. By the mid-1970s, children younger than 2 were drinking about three times the amount of added sugars than adults.

Today, the amount of added sugars per capita in the US is comparable to what it was in 1985

Numerous studies show the amount of soda consumed by both adults and children has been falling for some time. The consumption of sodas and other drinks sweetened with sugar fell for adults and children between 2003 and 2014, according to a 2017 study from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, by 11.5% and 19%, respectively.

A 2011 study reported that between 1999–2000 and 2007–2008, the consumption of added sugars decreased, primarily due to a drop in soda consumption. And even though adolescents and young adults continued to consume these drinks, a 2020 report published in the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics found that the percentage of Americans who drank more than 500 calories worth of sugar-sweetened beverages daily fell dramatically from 2003 to 2016.

So what has all this decrease led to? In 2021, total caloric sweeteners in the U.S. were 127.3 pounds per capita, only 1.1 pounds per capita more than in 1985. Total caloric sweeteners per capita have been falling steadily at a rate of about 1.2 pounds per capita annually.

The overall rise and fall of added sugars is mirrored in the availability of high fructose corn syrup

The drop in high fructose corn syrup usage is partly linked to the increased sales of bottled water and artificially sweetened sugar-free drinks, according to the USDA. The use of other corn sweeteners, glucose syrup, and dextrose also has fallen.

Manufacturers embraced high fructose corn syrup in the 1980s as tariffs drove up the price of sugar. But health-conscious Americans concerned about obesity have begun turning away from sodas and other products sweetened with high fructose corn syrup, prompting manufacturers to omit it from products.

A rise in the cost of corn has also contributed to this drop. As a result, since 1999, when high fructose corn syrup volume in the U.S. reached a historic high of 65.9 pounds per capita, there has been a 40% drop in its use.

Decreasing the added sugar in your diet can help avoid various health issues

The CDC makes no bones about it: Americans are eating and drinking too much added sugar, largely in the form of cakes, pies, brownies, soda, candy, and other sweets. As a result, they're suffering from an increased propensity for weight gain and obesity, Type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease (not to mention cavities).

Eating foods that naturally contain sugar, such as whole fruit, is better for your health because your body digests those foods slowly, providing your cells with a steady supply of energy, according to Harvard Medical School. They also supply fiber, essential minerals, antioxidants, protein, and calcium.

Adult men eat an average of 24 teaspoons of added sugar daily, equal to 384 calories, according to the National Cancer Institute. One 15-year study found that people who took in 17-21% of their calories from added sugar had a 38% higher risk of dying from cardiovascular disease than those who kept their consumption to 8%.