How the US compares to other countries on policies that could mitigate homelessness

This story originally appeared on Foothold Technology and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

How the US compares to other countries on policies that could mitigate homelessness

In late February 2023, the Department of Housing and Urban Development announced it was allocating $5.6 billion in grants to finance community programs, including affordable housing development plans and assistance for people experiencing homelessness or who are at risk. The grants benefit all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the five U.S. nonstate territories.

According to HUD, the Biden administration has exceeded its annual goals for mitigating homelessness by 25% until 2025, an ambitious objective outlined in the federal strategic plan launched in December 2022.

Despite the government's efforts, the U.S. does not consistently rank well compared to other member nations of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development regarding policies to resolve homelessness, particularly when measured against countries of comparable economic stature.

The problems, though similar, differ widely among nations due to population, public policy, geographical and weather conditions, income inequality, and health care systems. The same applies among the states; two densely populated states, New York and California, rank alongside one of the least populous states, Hawaii, making up the top three states in people experiencing homelessness. In 2020, they were the only three states with more than 40 people without homes out of every 10,000 inhabitants. The homelessness rate in D.C. far surpasses that oven even the worst-off states, with more than 90 people in 10,000 without a home.

The COVID-19 pandemic slowed down the already lethargic progress of the U.S. in addressing the homelessness crisis, though it is still uncertain how much the pandemic truly affected the situation.

While Congress, HUD, and local governments handed over billions of dollars in emergency aid to properly quarantine and protect the unsheltered, even demanding that hotels provide temporary accommodation for hundreds of persons, data gathering became a distinct challenge. Eviction prompted by rental nonpayment was halted thanks to policies such as the federal eviction moratorium and parallel programs at local levels, yet any change in the number of unsheltered homeless remains nebulous due to insufficient data gathering and the general difficulty in tracking individuals with no constant point of origin.

Experts agree on one thing: The pandemic exposed the brittleness of existing sheltering resources and the long road ahead toward finding a lasting comprehensive solution. The aim is to provide not only affordable housing, but also sustainable answers to the many factors that force people into homelessness, including social reintegration programs, mental health care, substance abuse treatments, and a safe haven for domestic violence victims.

Foothold Technology cited data from OECD to visualize how U.S. housing stock and policies compare to other countries and what that means for reducing rates of homelessness.

The relative dearth of US housing stock is a primary impediment to aiding the unsheltered homeless

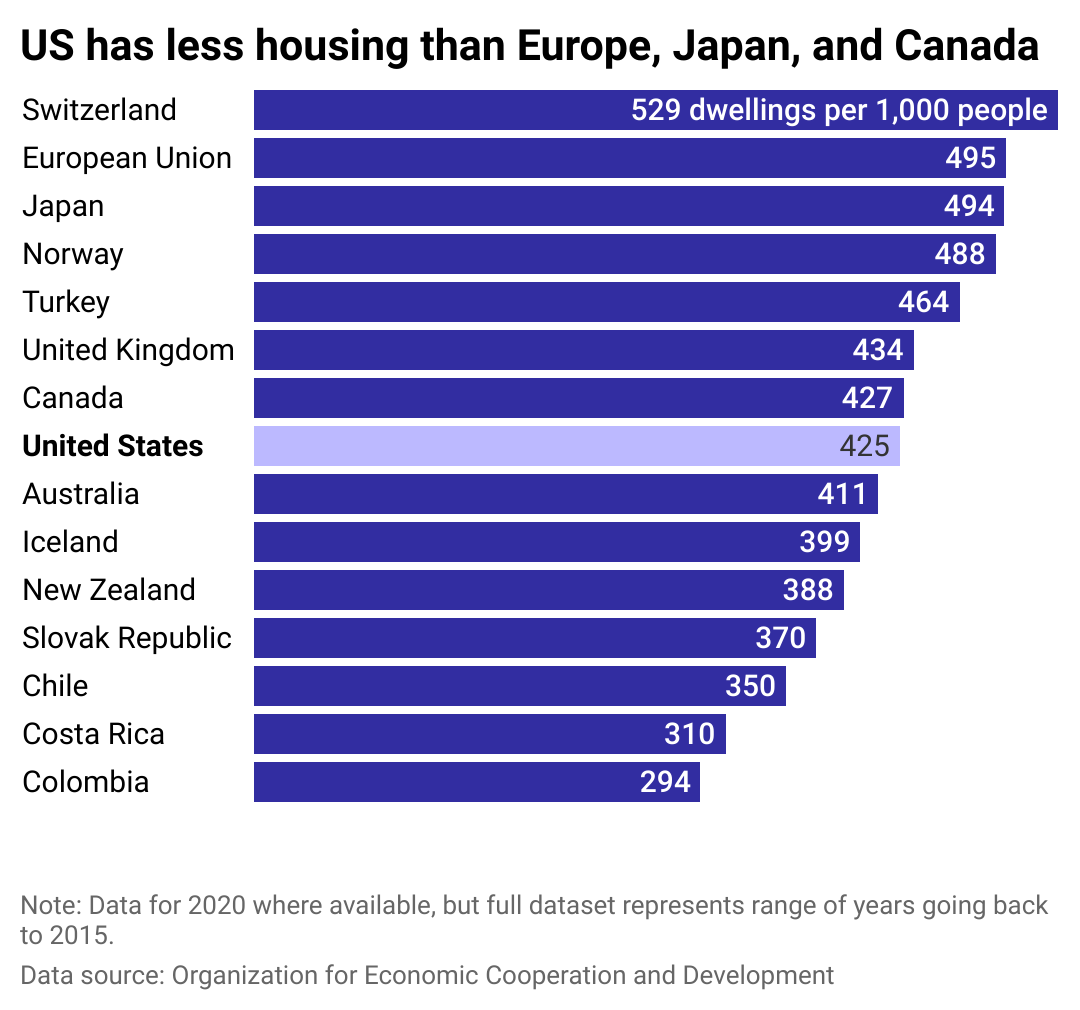

The number of dwellings—rooms or groups of rooms intended for habitation—per 1,000 inhabitants determines the adequacy of the housing stock or available structures built for private habitation in a country.

OECD statistics show that Western Europe is well ahead of the United States in housing stock, as are Japan and Canada. Turkey was also better off than the U.S. until the earthquake that struck the country on Feb. 6, 2023, along with its aftershocks, destroyed roughly half a million apartments, driving the country into a severe homelessness crisis.

The disaster proved that adequate housing means not only shelter, privacy, and comfort, but also the need to enforce construction regulations that ensure the safety and protection of people even under the most dangerous and unforeseen circumstances.

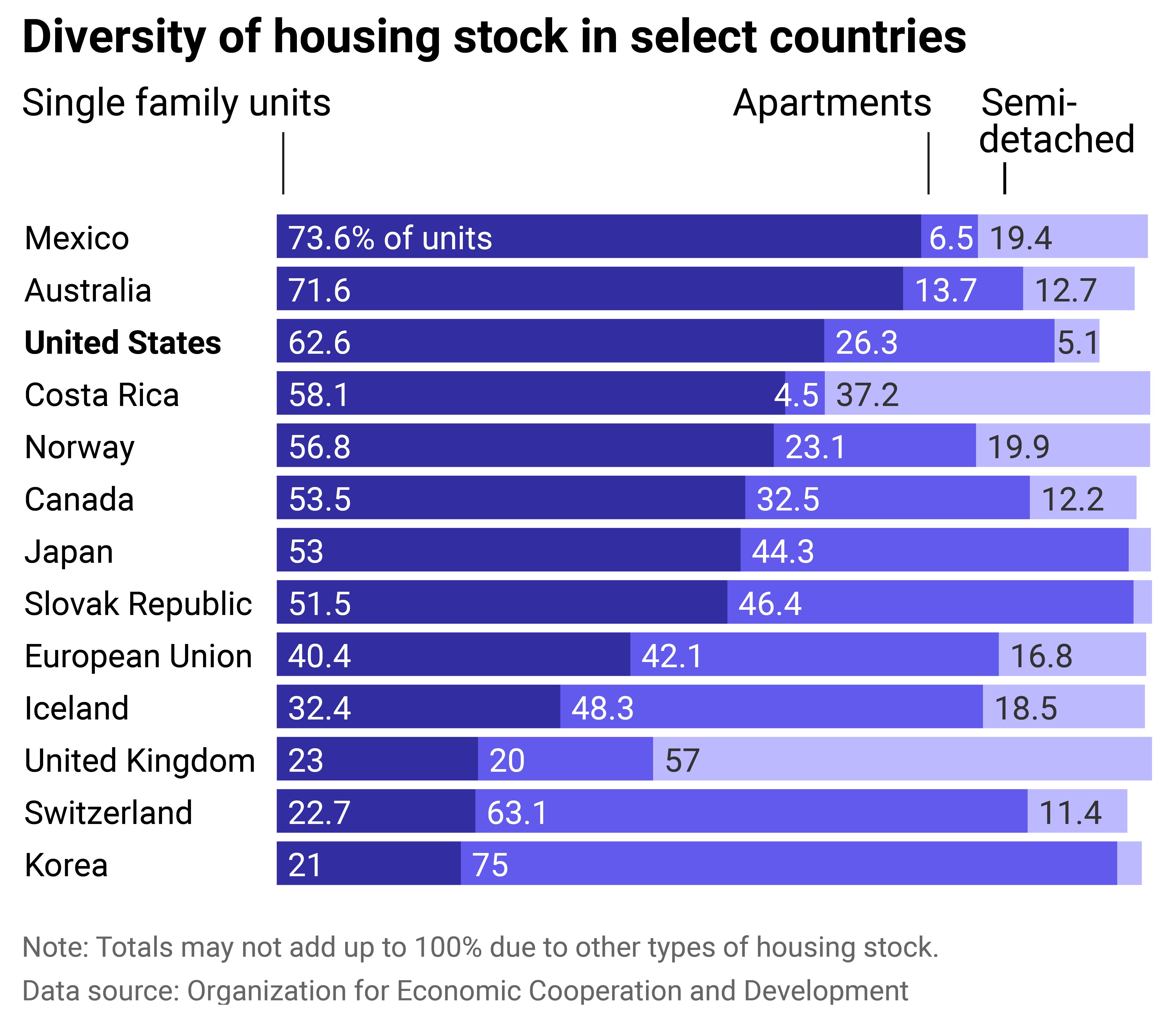

America has traditionally been a house-centric society, which presents a distinct hurdle to advancing the housing of the homeless

Walk around the center of Rome, Paris, or Madrid, and you will find clothing stores or restaurants on the ground level of apartment buildings. European cities built 1,000 years ago or more have progressively adapted their living conditions and zoning regulations to modern times.

The opposite happened in younger (and geographically larger) countries such as the United States and Canada.

Zoning in the U.S. is typically determined and implemented at the state and local government levels. Safety, convenience, and practicality are among the considerations when a plot of land is zoned for development. Still, single-family homes tend to win out as a means of sustaining existing home values. They also perpetuate the American tradition of the neighborhood versus mixed-housing developments that place detached homes and multi-unit structures like apartment buildings in the same development location.

In most American cities, residential, commercial, and industrial areas are defined during the urban planning phase. Therefore, zoning regulations become rigid as these varying forms of structural developments are determined.

Apartments, flats, condos, studios, or lofts in large multi-unit buildings are the reigning housing type in several century-old and high-density European and Asian cities with limited empty land to grow, particularly in national capitals or industrial hubs. Some cities in the U.S. have begun to turn away from the traditional focus on single-family homebuilding and toward other housing forms.

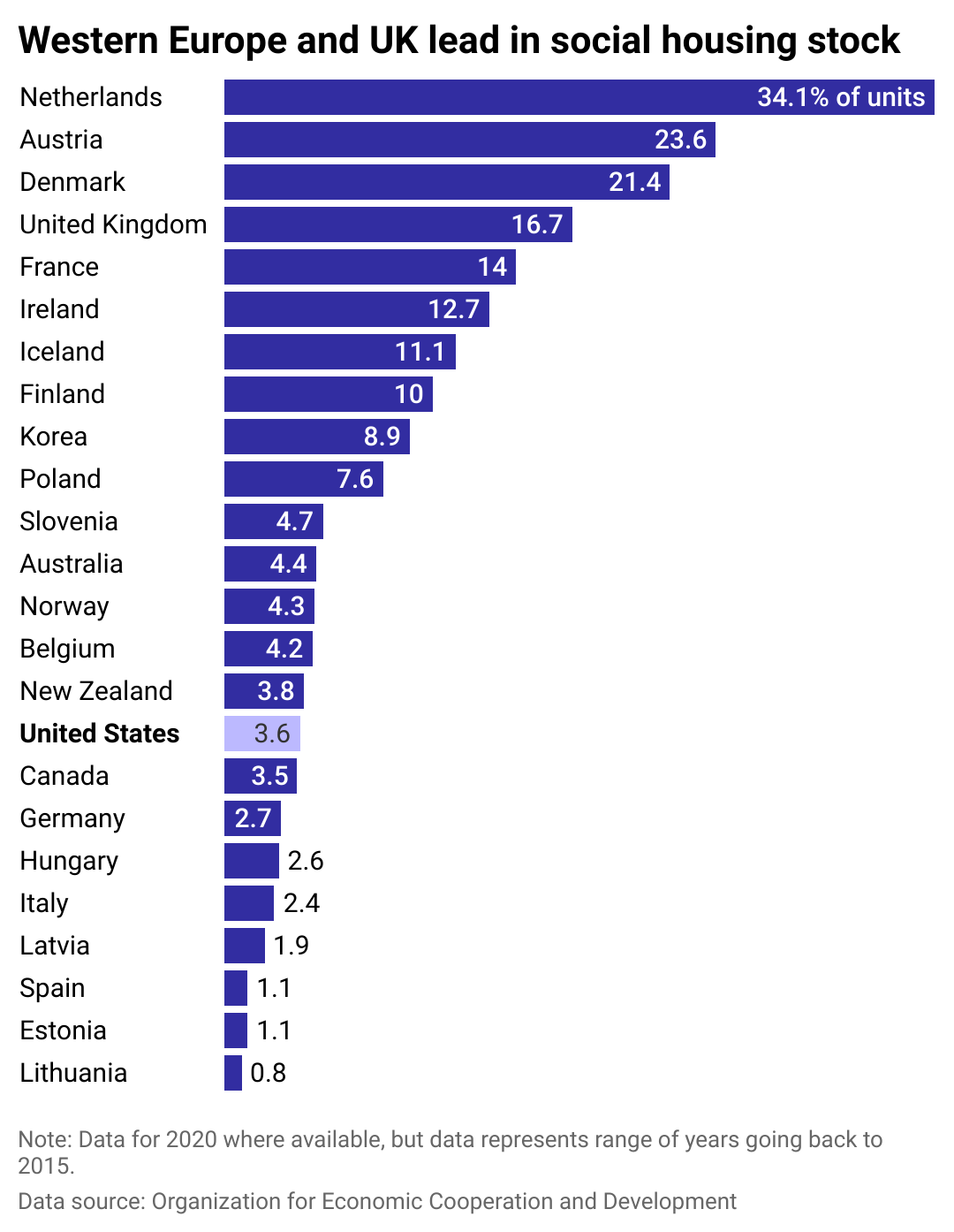

The US lags behind most other developed nations in public housing

The countries of the European Union differ significantly when comparing their social (read: government-subsidized) housing programs.

Austria is one of the OECD countries with a high rate of social housing. It has succeeded not only in providing lower- and middle-income citizens with affordable living options, but managed to incorporate these subsidized dwellings into community development without the stigma they are viewed with and the implicit segregation they are exposed to in the U.S.

In Germany, on the other hand, the government leans toward subsidizing renters over owners, despite the fact that most multi-unit structures are owned by private landlords and not the government itself.

People living in OECD countries must meet specific criteria to qualify for social rental housing. Families with children and seniors usually have priority over single adults. Income also plays a role as the dwellings are not allocated through regular market mechanisms. In Europe, some countries have housing programs for college students, recent graduates, and young couples aimed to help them jump-start their life without extra burdens.

In the U.S., public housing has become synonymous with "affordable housing," a term that often functions more as a political signifier than a viable mode of residential development. There are, however, states in the U.S. that have begun to make progressive strides toward increasing the availability of public housing and, in turn, divorcing it from the stigma of being a blight on community development.

In June 2022, the Rhode Island legislature approved a $10 million pilot program that will build affordable housing units across the state, and Colorado passed a bill to create a housing authority that will create thousands of housing units devoted to middle-income families.

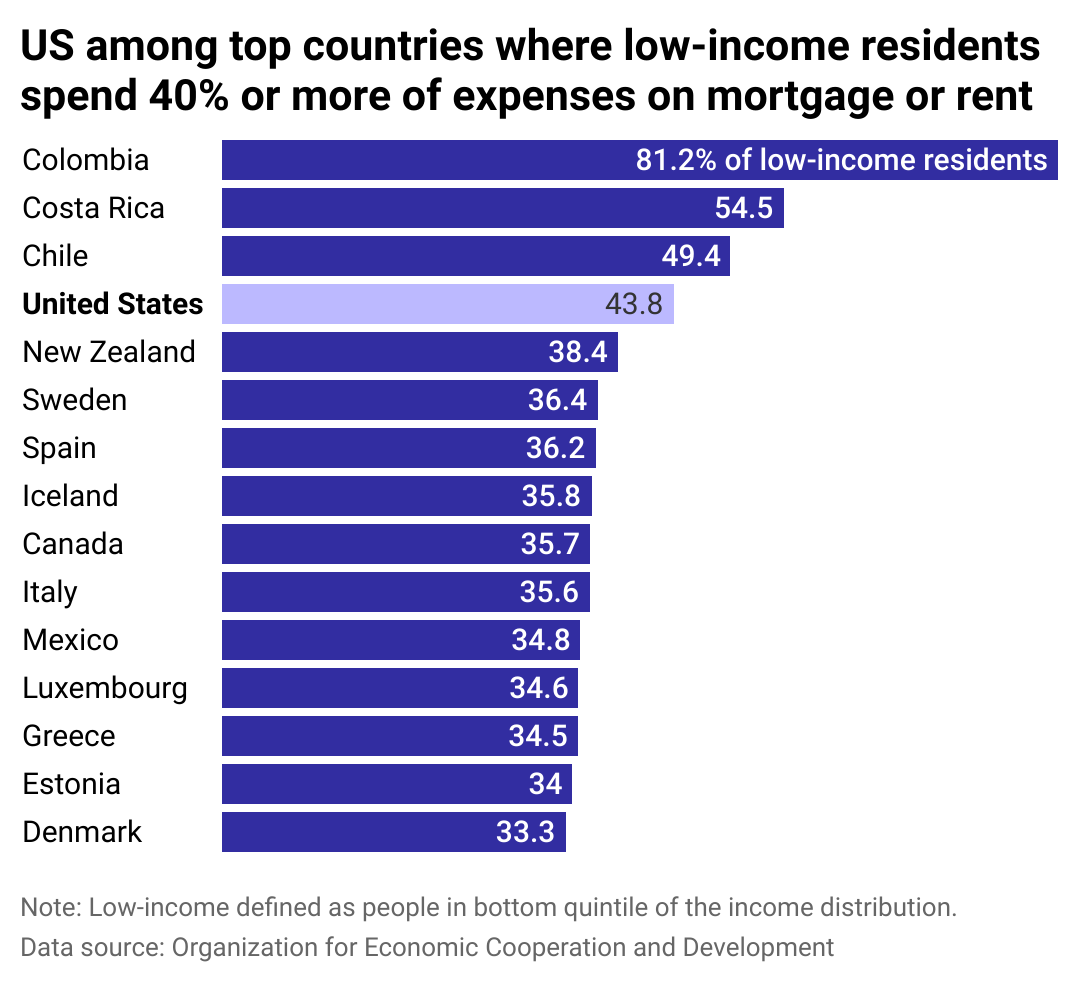

Overburdened housing costs create inequity for low-income residents

According to the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, stable, adequate, and affordable living conditions provide people with a "platform for improved outcomes around employment, health, and education." And yet in the U.S., low-income people spend nearly half of their income on rent or mortgage. This has become a deepening problem over the past year, as wages have failed to keep up with inflation, which has reached historic levels.

Moreover, in an effort to curb inflation, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates seven times in 2022, with further increases coming in 2023. Higher interest rates have made home financing more difficult for lower-income families and increased the burden on renters, as higher rates have increased the cost of borrowing on landlords and property developers.

One of the most concerning effects of homelessness relates to the young. Children and teenagers who experience homelessness are more susceptible to developing mental health problems and dropping out of school, which jeopardizes their chances of eventually prevailing in the labor market.

Another factor contributing to unaffordability in urban housing is gentrification, as exemplified by the ongoing situation in San Diego, where traditionally working-class neighborhoods have become unaffordable to most residents—especially senior citizens, and in some cases forced them into homelessness.

Cities like San Francisco, New York, and Chicago all face similar problems.