Within the gender housework gap, laundry is one of the most unequally divided tasks

This story originally appeared on Hampr and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Within the gender housework gap, laundry is one of the most unequally divided tasks

More American men took time off after the birth of their first child than ever before over the past few years. Women have outpaced men in college degree acquisition rates for decades, and young women earn just as much as young men, if not more than them, in many U.S. cities.

Despite all appearances that American society is moving swiftly toward gender equality, the amount of time women spend on unpaid housework compared to men remains distinctly unequal. On an average day, women spend nearly 40% more time on unpaid caregiving and housework than men, according to an analysis of 2018 data by the Institute for Women's Policy Research, published in 2020.

Why have such gender divides persisted? Hampr analyzed data from the American Time Use Survey, Gallup, and the Pew Research Center and used historical and academic research to get the inside scoop on the gender housework gap. It's worth noting the majority of existing data and research on the gender housework gaps focus on dynamics between women and men, and little information on the subject exists regarding queer and gender nonconforming people. Additionally, most studies have historically focused on the gender gap between white men and women, and more research is needed to determine how the gender housework gap varies based on race and more expansive gender identities.

Previous studies, however, have shown that expectations around housework and caregiving responsibilities negatively affect women's earning power. For one, many women work less or need to take on lower-paying, more flexible jobs to attend to unpaid caregiving responsibilities—a move that reduces their wages.

Another major factor is the lost wages and career momentum many women face when they go on parental leave. Racial discrimination, as well as bias against LGBTQ+ and workers with disabilities, further complicates the gender pay gap.

Meanwhile, research shows that men benefit financially from women taking care of domestic responsibilities, while women's salaries suffer. Researchers have suggested that reducing women's involvement in housework and caretaking could be an important factor in closing the gender pay gap. However, women who outearn their husbands still spend more time on housework and childcare than their male partners.

More advanced technology doesn't mean less time spent on housework

It's difficult to pin down the origins of ideas about traditional gender roles and "women's work"—they are seemingly organizational structures that have existed forever. Asked to point to a specific era defined by these gender roles and norms, many people would single out the 1950s and '60s, a time collectively remembered as the golden age of the housewife.

But the idea of that time is just that: an idea, according to Kate Mangino, a gender equality expert and author of the book, "Equal Partners: Improving Gender Equality at Home."

"There was a myth of the stay-at-home mom and the working dad and the nuclear family," Mangino told Stacker, clarifying that in many families, both rural and urban, both parents worked a great deal. "It was really only a certain socioeconomic class that could afford to have someone stay at home."

Movies, television, and advertisements attempted to sell both women and men the concept of the ideal domestic woman, fulfilled by unpaid cleaning, cooking, and caretaking. Still, the reality of most Americans outside of the white middle and upper class was starkly different. Wealthier white families also employed many women of color to perform the tasks associated with the white housewife.

It wasn't until after World War II that many American households began to own electric washing machines, which replaced their usual laundry workers. Without these hired hands, however, women took over the responsibility of doing family laundry.

Today, outsourcing tasks like laundry is still primarily a luxury enjoyed by those with the means. Outsourcing, Mangino said, "buys you more time that you have for work or for your family, whereas if you do not have those privileges, then you're going to have to figure out a way to do it yourself or lean on friends and family and neighbors to provide those for you."

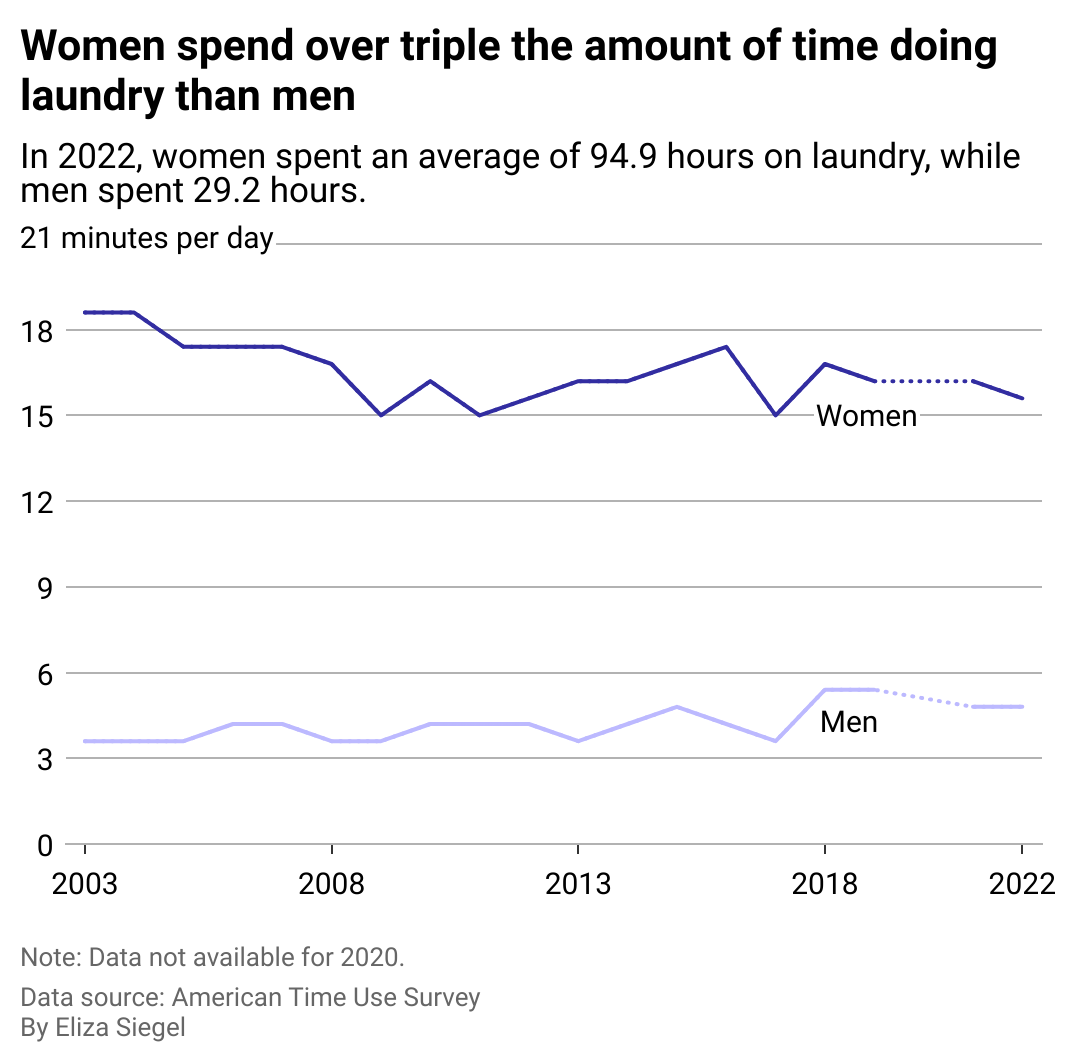

Laundry is still disproportionately performed by women. Although the last two decades have given rise to marginal changes—women spend an average of a few minutes less per day on laundry than they did 20 years ago, while men spend a couple of minutes more—the gap remains significant.

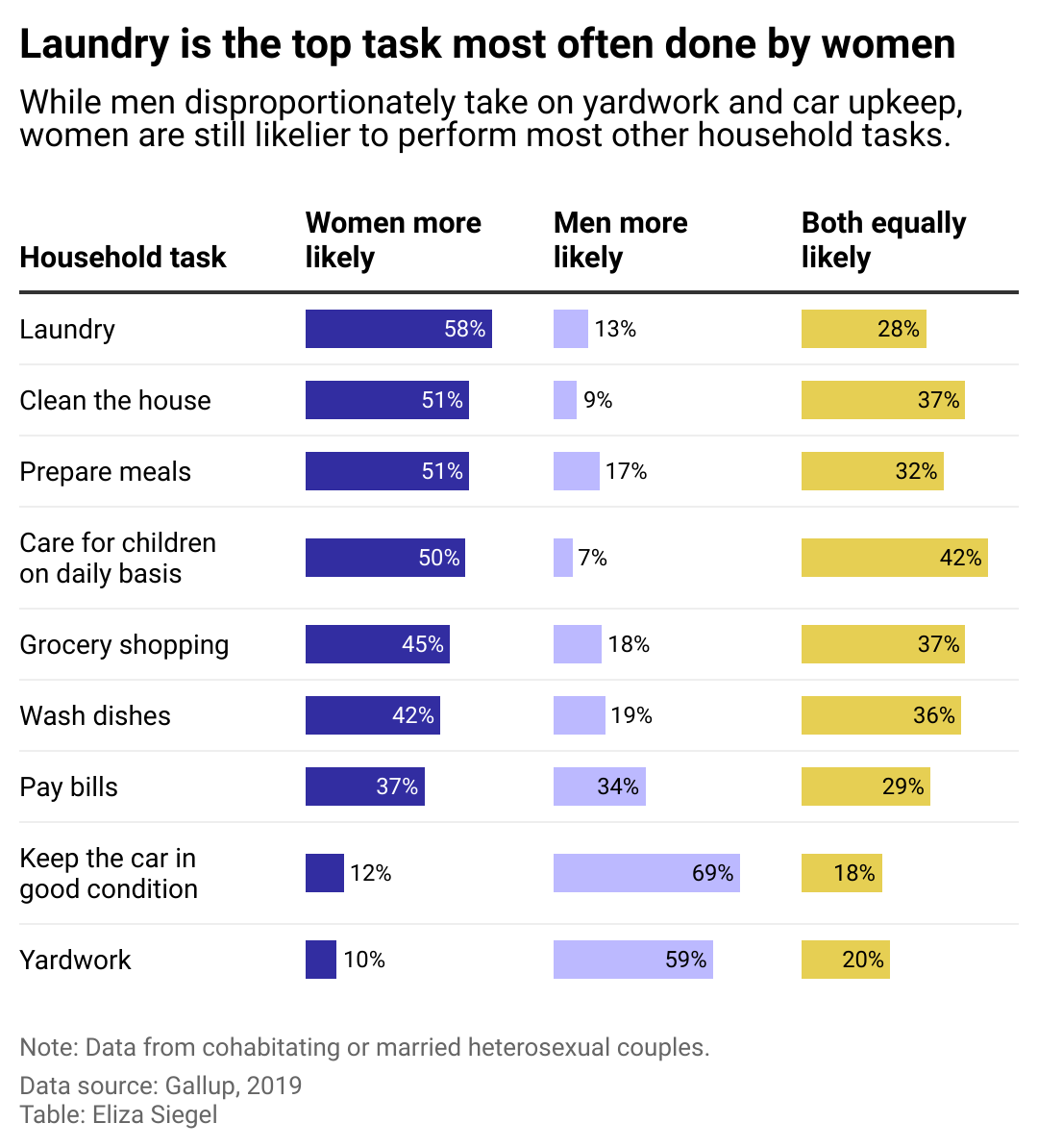

Chore types remain very gendered

Within the domain of household tasks, some, like laundry, cleaning, and cooking, are still disproportionately performed by women. Other chores, like yardwork and keeping the car in good condition, are done predominantly by men. Sociologists have extensively studied this gendered division of labor, classifying different types of housework as male- and female-coded.

"Female-coded tasks tend to be routine and indoor, and male-coded tasks tend to be intermittent and outdoor," Mangino said. While male-coded, intermittent, and outdoor tasks like lawn care and car maintenance are certainly laborious and valuable, they don't need to be done daily or even weekly. "If something else comes up and you're sick or you have to do something at work or you take a vacation, if you skip a week mowing your lawn, it's not a real problem," Mangino noted.

On the other hand, female-coded routines and indoor tasks, such as cooking, cleaning, and caretaking, need to happen every day. "If you miss a day because you're sick or something comes up at work, you might be able to get by for one day by ordering pizza and letting the dishes pile up in the sink. But if you let it go for more than one day, it's a major issue," Mangino said.

While many households may not strictly adhere to this division of labor, many do, keeping women on the hook for household management and caregiving.

"Nothing in our DNA or hormones prevents any human from being an exceptional caregiver," Mangino said. "It's all about experience and exposure. But I think because we've normalized women caregiving and we've normalized women managing households, those norms continue to persist."

Systemic inequalities and individuals perpetuate the gender housework gap

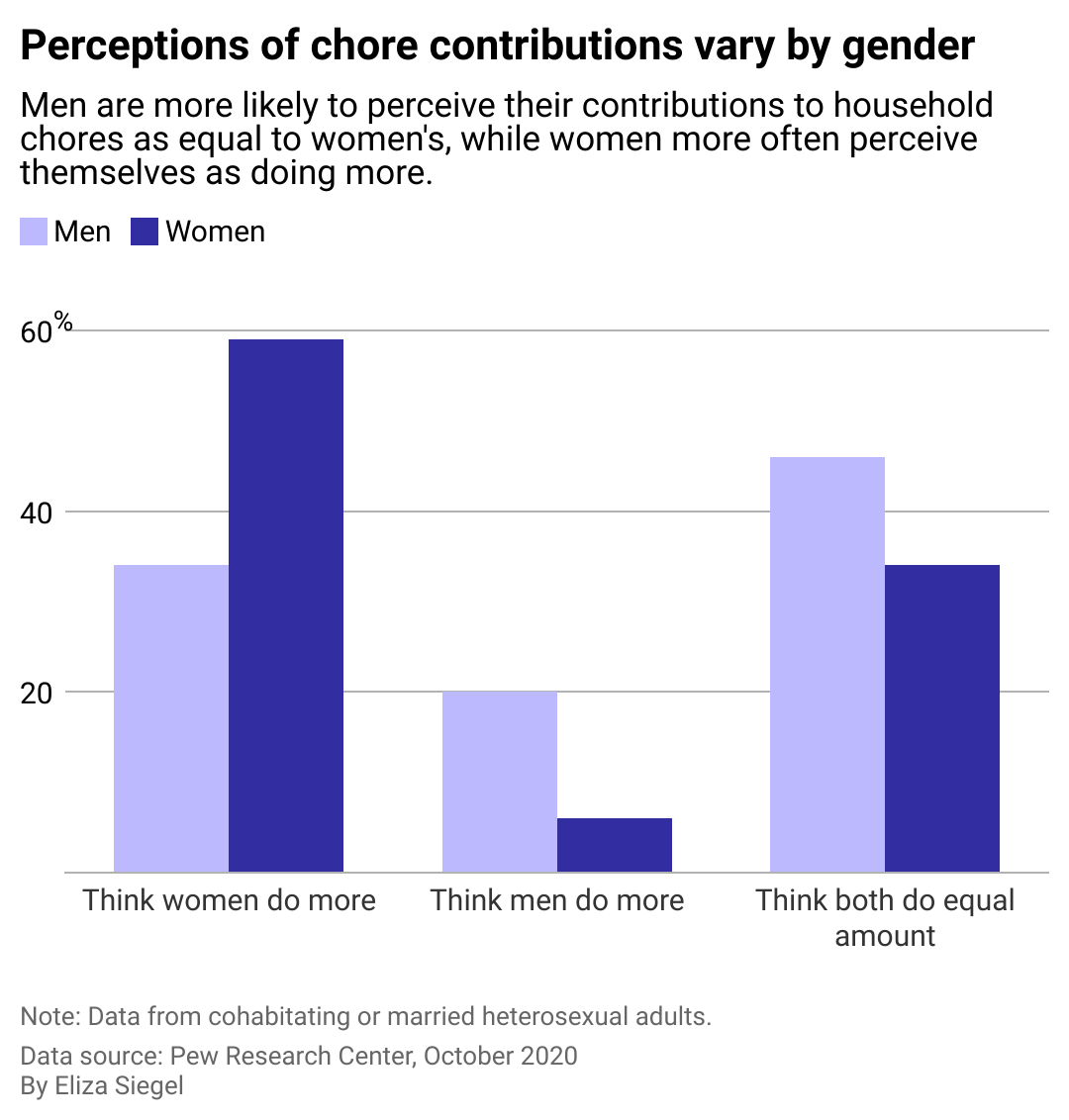

Just as the gender division of labor in households is deeply unequal, perceptions of who is contributing—and how much—are also skewed. Nearly half of men think they participate in housework just as much as women, and 1 in 5 believe men do more housework than women, according to 2020 data from the Pew Research Center. Meanwhile, nearly 3 out of 5 women think they do more housework, an accurate perception backed up by overwhelming evidence.

According to Mangino, structural issues such as the lack of a federal paid family leave policy, prohibitively expensive childcare, wages that have not kept up with rampant inflation, and the lack of benefits for many low-wage workers all contribute to the continuation of the gender housework gap, among other inequities.

Even workers with paid family leave benefits often face professional penalties for using them—men, in particular, are implicitly or openly discouraged from taking time off work to care for their families, Mangino said.

For Sarah Johal, the founder and CEO of the nonprofit CareSprint, business leaders do their workers a disservice by not tracking employees' caretaking responsibilities and integrating them into their benefits policies.

"Companies are already having to aggregately report their outcomes for gender, race, ethnicity, job levels. This is the gold standard of corporate diversity reporting, but caregiving isn't there at all, so you have an enormous segment of workers, primarily women, who are going ignored in that experience," Johal told Stacker.

Apart from advocating for structural changes that would help narrow the gender housework gap, Mangino said that individuals must also approach the division of labor in their own households with intentionality and equity in mind.

"Both people need to be able to say, 'Okay, this is the pattern. This is the norm. This is our history,'" Mangino said. "'So we're not going to let that happen. We're going to be intentional. We're going to make changes in our home.'"

Story editing by Carren Jao. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.