This story originally appeared on ADHD Advisor and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

South Carolina ranks #36 in mental health care deserts

Mental health stigma is largely on the decline in the United States, allowing more people than ever before to pursue care. Yet other barriers—including a shortage of mental health professionals—present ongoing problems for those who would otherwise seek help. More than 1 in 10 Americans lack adequate access to mental health care, according to the Department of Health and Human Services.

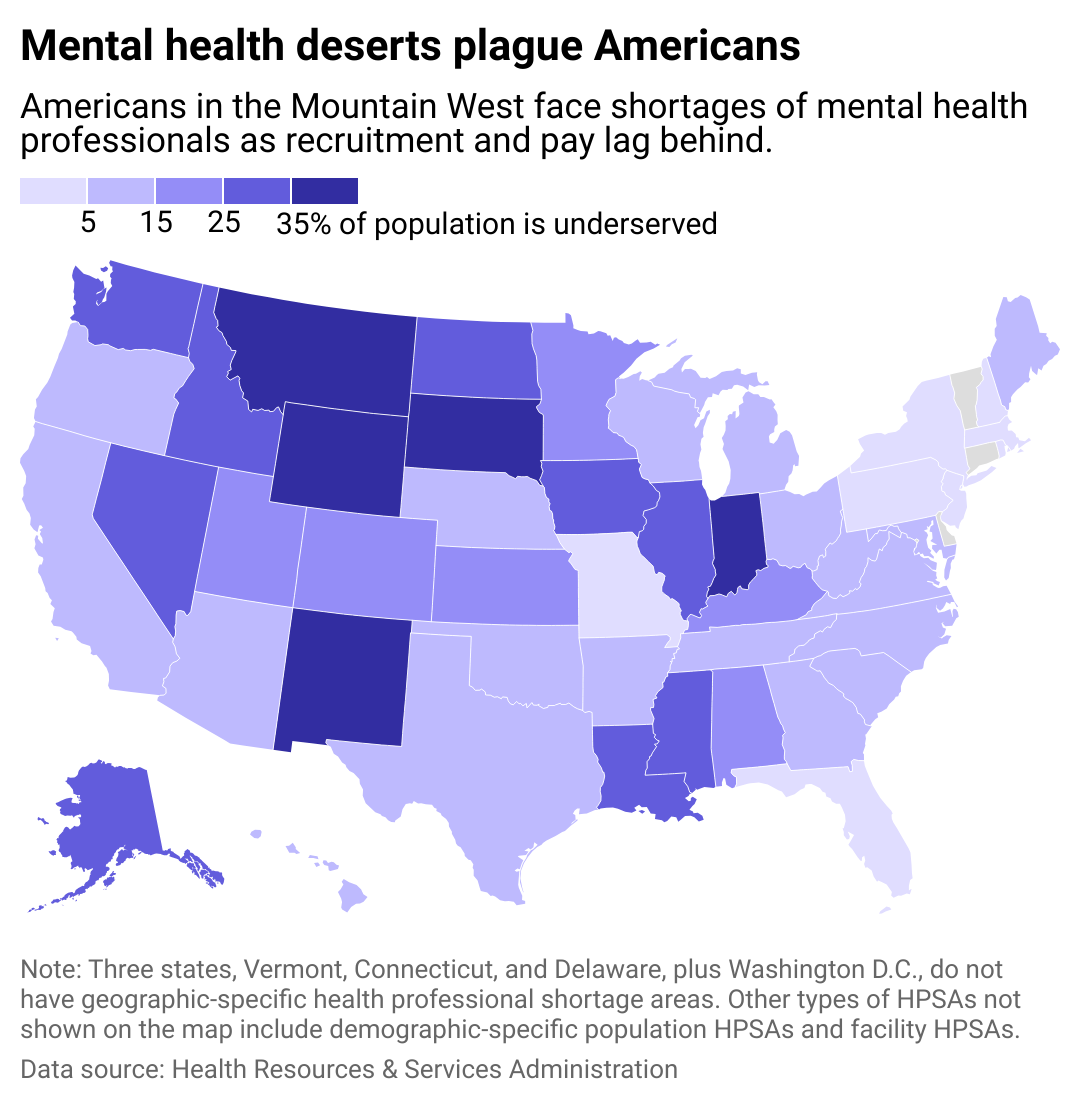

ADHD Advisor used data from the Health Resources & Services Administration to map and analyze mental health provider shortages across the United States. An area is considered underserved if it has fewer than 1 provider for every 30,000 people or a ratio of 1 to 20,000 for high-need communities. While this analysis focuses on geographic shortage areas, other designations can impact specific demographics or facilities like prisons.

Lack of access to mental health care can have long-term effects in regions across the U.S., including the lack of a proper diagnosis or an individual turning to drugs or alcohol to self-medicate. For those who do get diagnosed, including those with ADHD, insufficient mental health care access may prevent people from seeking help or managing their medications properly. This is particularly true in rural counties, where existing, limited access to care—including long wait times and far distances to travel for care—was further disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

South Carolina has 5 designated geographic mental health shortage areas, covering 20 counties. About 398.6K residents are underserved, or 7.4% of the state's population. Read the national analysis to learn more.

In 5 states, more than 35% of the population is underserved

The mental health provider shortage impacts people in communities throughout the U.S., with South Dakota, Wyoming, New Mexico, Indiana, and Montana facing the most severe shortages.

It's an ongoing cycle: Provider shortages mean doctors and clinicians are in charge of expansive caseloads, which can lead to burnout and increased retirements. In New Mexico, for example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates the state needs at least 61 mental health professionals to ease the burden—but low pay makes it difficult to recruit people from out of state.

Lawmakers have come together at the local and federal levels to remedy this.

The Biden administration has poured billions of dollars into increasing access to care, including grants to increase the pipeline of mental health professionals in high-need areas. States are also taking an active role by offering monetary incentives, including student loan reimbursement. Apprenticeship programs can also help stem some of the shortage in high-need areas. In Alabama, for example, students getting their master's degree in social work at the University of Alabama can get real-world experience while getting paid.

While there's no one-size-fits-all approach to remedying the mental health crisis, its impacts are being felt across the country. In 2020, Americans spent about $280.5 billion on mental health and substance abuse treatments, with about a quarter coming from Medicaid spending alone.

This story features data reporting by Elena Cox and Paxtyn Merten, writing by Elena Cox, and is part of a series utilizing data automation across 47 states.