25 facts about nuclear weapons

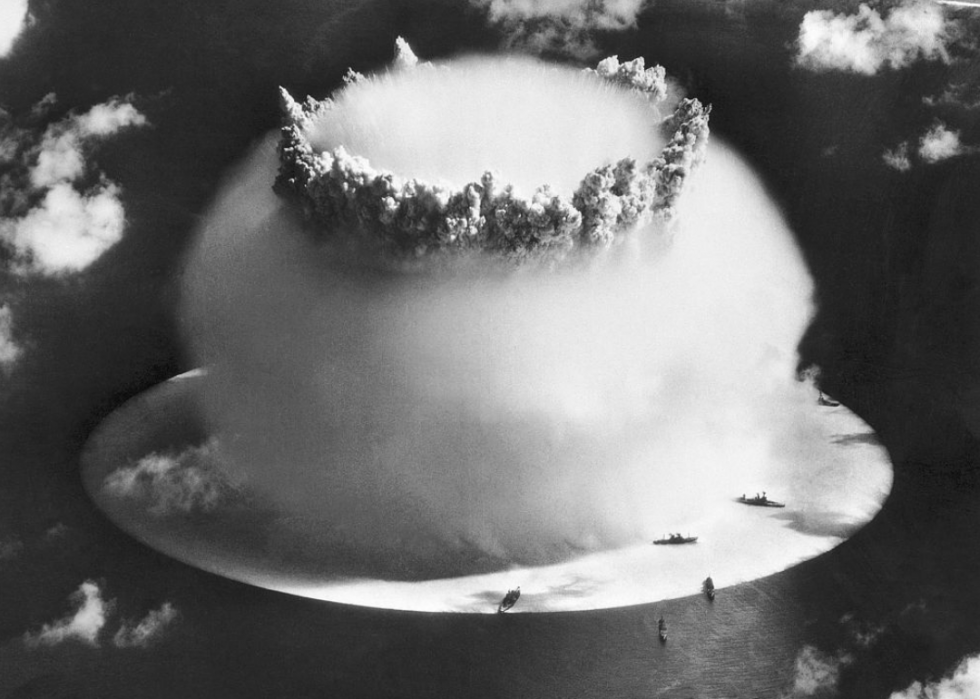

The early years of nuclear weapons were marked by an arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union. Although the United States built the first nuclear bombs, dropping them on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II, the Soviet Union's nuclear program was not far behind. By the beginning of the 1950s, both countries had even more powerful weapons—hydrogen bombs.

Each side built more and bigger bombs until the stockpiles peaked in the late 1960s at 31,255 for the United States and 40,159 for the Soviet Union. One bomb that the Soviet Union developed, known as the Tsar Bomba, was too big to use. When it was tested in 1961 on Novaya Zemlya, an archipelago in the Arctic Ocean, it destroyed all of the houses in a village 34 miles from ground zero.

Today the stockpiles have shrunk, but the battles over nuclear weapons remain and feature new actors. Experts say North Korea could have materials for as many as 100 nuclear bombs, and although Iran insists its nuclear program is for peaceful use, there is concern over whether it will develop weapons. Meanwhile, the trauma of nuclear warfare runs deep in societies affected most by it; the Oscar-winning blockbuster "Oppenheimer" was only recently released in Japan (with content warnings for viewers) eight months after its initial debut, due to concerns about the consequences of downplaying the after-effects of the devastating bombings that ended World War II.

Using government documents, news reports, and academic studies, Stacker compiled 25 facts and events that shaped the state of nuclear weapons in the world today.

Countries armed with nuclear weapons

According to security experts, nine countries now have nuclear weapons (whether acknowledged or not): the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, China, India, Pakistan, North Korea, and Israel. Israel has neither confirmed nor denied the existence of its weapons. The United States and what was then the Soviet Union were the first to develop them, followed by the United Kingdom, France, and China.

Trying to stop nuclear proliferation

The United States and other countries hoped to stop the spread of nuclear weapons with the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, which went into effect in 1970. Since then, 191 states have joined, including the five so-called nuclear weapons states—the U.S., Russia, the United Kingdom, France, and China. These countries were allowed to keep their weapons but are supposed to be reducing the number of them they have.

Refusing to agree to the accord

India, Pakistan, and Israel, all of which have nuclear arsenals, never signed the treaty. Israel is believed to have about 100 weapons. North Korea withdrew from the pact in 2003 and, since 2006, has tested nuclear explosives a number of times.

Large arsenals of the late 1960s

At its peak in 1967, the U.S. had 31,255 nuclear weapons in its stockpile. The Soviet Union topped that with 40,159 in 1968. Globally, the numbers have dropped overall; however, more countries now have nuclear weapons.

China's "modest" nuclear weapons stockpile

China has what the Union of Concerned Scientists classifies as a relatively modest nuclear arsenal of about 250 warheads and bombs, of which fewer than 100 could reach the U.S. China conducted its first nuclear test explosion in 1964. The country's limited number of nuclear weapons can be traced back to the attitude of its former chairman, Mao Zedong, who called them "paper tigers."

Lost bombs and other missing nuclear devices

According to the Brookings Institution, the United States has never recovered 11 nuclear bombs lost in accidents. Four were aboard a plane that crashed in Greenland in 1968, contaminating a fjord when the weapons broke open. A 1989 study found that 50 warheads and nine nuclear reactors had been lost at the bottom of the ocean as a result of accidents involving the U.S. and the former Soviet Union.

To launch or not in 12 minutes

If missiles were believed to have been launched at the U.S., the president would have only about 12 minutes to decide whether to counter with a retaliatory intercontinental ballistic missile—what is known as the launch-under-attack option.

Assassinating Iran's top nuclear scientists

Since 2007, Israel is believed to have assassinated seven scientists and military officials essential to Iran's nuclear program. The first was a nuclear scientist who died in a gas leak at a uranium plant. Among the most recent was in November 2020, when Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, Iran's top nuclear scientist, was ambushed and shot to death. Iran says its nuclear program is for peaceful use, but there is widespread concern that the country will work to develop weapons. Americans and Israelis say Fakhrizadeh was crucial to Iran's nuclear weapons development.

Blackout at Iran's nuclear fuel enrichment facility

A power failure caused by an explosion at Iran's primary nuclear fuel enrichment facility in Natanz in April 2021 set Iran's nuclear program back nine months. Israelis are believed to have played a part in the explosion. In July 2020, a different explosion destroyed part of the same facility, and intelligence officials say Israel was also responsible for that attack.

U.S., Iran negotiate nuclear deal

Under President Biden, the United States is negotiating with Iran to try to revive a nuclear agreement that would limit Iran's production of nuclear fuel in return for relaxing sanctions that have crippled its economy. The deal went into effect under President Obama, but it was scuttled by President Trump. As of April 2023, the administration is exploring a "freeze for freeze" approach that would call for Iran to reduce its nuclear development program in exchange for relief from certain sanctions.

Iran steps up uranium enrichment

In response to the attack on its main nuclear facility in Natanz, Iran announced that it was enriching uranium at 60% for the first time. This was one of several moves Iran made in response to sanctions that would cut the time necessary to develop a nuclear weapon. It also announced it would install extra centrifuges needed for uranium enrichment and begin producing uranium metal used in a weapon's core; the country has refused U.N. inspectors daily access to its sites.

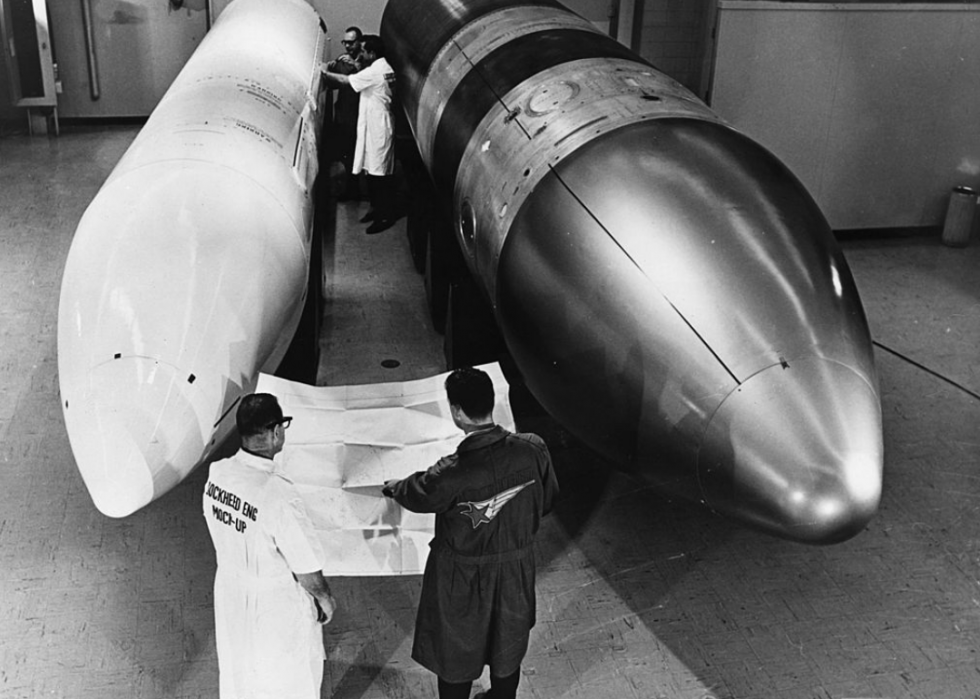

A weapon as large as a minivan

The B53 bomb went into service in 1962. The heaviest nuclear weapon in the U.S. arsenal after the Cold War, the bomb weighed 8,850 pounds and was about the size of a minivan. In 1997, the bombs were taken out of the active stockpile, and in 2011, they were finally disassembled.

Largest weapon in U.S. stockpile

The largest known weapon currently in the U.S. stockpile is the B83, a 1.2-megaton bomb. Its explosive power is 80 times that of the bomb the U.S. dropped on Hiroshima.

Billions for nuclear deterrent

According to the Congressional Budget Office, the projected cost of the U.S. nuclear forces from 2021 to 2030 will be $634 billion. The lion's share of these funds will be handled by the Department of Defense; early-warning systems alone will see $49 billion dedicated to development and maintenance, breaking down to approximately $4.4 billion per year.

$600 billion to modernize nuclear arsenal

The United States would need to spend $600 billion through 2030 to modernize its nuclear arsenal, which covers operating costs, extending the life of its nuclear weapons, and purchasing new delivery systems for what's known as the strategic triad—bombers, intercontinental ballistic missiles, and submarine-launched ballistic missiles.

U.N. tries to ban nuclear weapons

A treaty whose goal is to eliminate nuclear weapons entered international law in late 2020. Sixty eight countries have ratified the accord, but none of the nine countries with nuclear weapons have. These countries boycotted the negotiations that brought about the treaty, and they are not bound by it if they do not sign it. The U.S. has argued that the treaty will not result in the elimination of a single weapon.

U.S. offers a "nuclear umbrella"

The United States provides a "nuclear umbrella," or guarantee of defense to its non-nuclear allies, including the member states of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) plus Australia, Japan, and South Korea. Japan demilitarized after World War II, though in 2014 then-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe lifted the ban on the military defending allies under attack.

Withdrawing forward-deployed weapons in the Pacific

The U.S. removed the last of its forward-deployed nuclear weapons, or those located in other countries, from the Philippines, Guam, South Korea, Taiwan, and Okinawa in 1991. At its peak in 1977, the country had 3,200 such weapons deployed in the Pacific region.

Estimates on North Korea's nuclear capabilities

Experts say North Korea could have materials for up to 100 nuclear weapons, and the country has tested ballistic missiles that could reach the U.S. North Korea has continued testing despite U.N. Security Council sanctions and summits with both South Korea and the U.S. regarding its nuclear weapons. In March 2023, North Korea revealed that it possesses small nuclear warheads capable of being fitted to short-range missiles.

North Korea unveils enormous new missile

Just before the U.S. presidential election in 2020, North Korea unveiled a large new intercontinental ballistic missile, parading it through the streets of Pyongyang. The Washington Post described the untested missile as one of the largest "road-mobile, liquid-fueled" ballistic missiles ever made and noted that the Hwasong-15, the largest missile before this, could likely reach all of the U.S. The U.S. and Russia have produced larger missiles, but those are powered by solid fuel and are kept in silos.

North Korea tests nuclear bombs

North Korea has conducted a number of nuclear tests, most during Kim Jong Un's time as the country's leader. The first bombs were detonated in 2006 and 2009 under Kim Jong Il; tests were then done in 2013, twice in 2016, and in 2017 under Kim Jong Un. North Korea said the last test was of a thermonuclear weapon. In 2022, North Korea conducted 63 missile tests, and while none contained a nuclear payload, the frequency of such tests may be a harbinger of the eventual development of further nuclear payload capability.

Trump, Kim Jong-un meet in historic summit

Kim Jong Un and former U.S. President Donald Trump attended a summit in Singapore in 2018, making Kim the first North Korean leader to meet with a sitting U.S. president. The summit ended with little substance, and Trump was criticized for giving credibility to Kim. However, some scholars argue that the talks showed Kim is rational and might be persuaded to hold off on new testing if the Biden administration promises something in return.

Second North Korea, U.S. summit held in Hanoi

In 2019, Kim Jong Un and former U.S. President Donald Trump met for a second time in Hanoi, Vietnam. The two-day meeting ended unexpectedly in the middle of the second day, and no joint statement was issued. The same differences that tripped up the first meeting—the definition of denuclearization among them—seemed to have played a role here.

Trump crosses into DMZ separating two Koreas

At their third meeting, former President Donald Trump crossed into the demilitarized zone separating North and South Korea and met for 50 minutes with Kim Jong Un. Nonetheless, no further progress was made on nuclear talks, and Trump was again criticized for giving legitimacy to Kim without any concessions.

Russia-Ukraine War raises concerns about Russia's use of nuclear arsenal

Russia's invasion of Ukraine in 2022 has meant mounting tensions not only in the immediate area but also between Russia and NATO allies. As of 2022, Russia has the largest arsenal of nuclear weapons in the world, closely followed by the U.S. Together, the two countries own 90% of the world's nuclear weapons. In September 2022, Russian President Vladimir Putin threatened the use of "all weapons available" in the event of an attack on Russia by Western allies of Ukraine, alluding to the nation's nuclear stockpile and emphasizing that the threat was not a bluff. U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken responded with a condemnation of Putin's threat, calling it "loose talk." Other U.S. officials underscored Blinken's point, stating that there was no indication that Russia was actually making moves toward employing a nuclear weapon.