12 times taxpayers footed big bills for new stadiums and arenas

12 times taxpayers footed big bills for new stadiums and arenas

Seven of the NFL's 30 stadiums cost more than $1 billion to construct, and five of those seven stadiums were built in the past decade, according to a dataset compiled by the Cincinnati Enquirer. Set to join that list is a new, $1.4 billion Buffalo Bills stadium due for completion in 2027, which is being built with $850 million in state and local funds. Needless to say, the construction of $1 billion dollar stadiums has gained steam.

The new Bills stadium is part of a larger trend of stadiums and arenas being built using, in significant part, public funds. One might well be excused for asking why public funds are necessary when most sports franchises are owned by billionaires (as is certainly the case with the Buffalo Bills and their fracking maven owner Terrence Pegula). Only a handful of NFL stadiums, all built more than 20 years ago, have not used public funds—and this trend is not exclusive to the gridiron, as Stacker compiled a list of 12 professional sports venues that drew heavily on public funding for their construction demonstrates.

Sifting through data from Marquette Law School, the Buffalo News, the Cincinnati Enquirer, the New York Times, MLB.com, and many other sources, we've listed them from the least to the most amount of public funding.

Little Caesars Arena (Detroit)

- Year opened: 2017

- Total cost: $863 million

- Public funding: $324 million

- Portion publicly funded: 38%

- Tenants: Detroit Pistons (NBA)/Red Wings (NHL)

“Pizza! Pizza!” That’s the ad slogan of Little Caesars, but its namesake sports arena might have instead been named “Money! Money!” Why? Because its construction required a whole lot of it from a Detroit public that, for the most part, can’t even afford the ticket prices to attend a Pistons or Red Wings game. The Detroit City Council fought off a lawsuit challenging their public funding decision, arguing that it should have gone to a public vote and that the funds would have been better spent on schools. Most of the public funds came from property taxes originally intended for local schools.

AT&T Stadium (Arlington, Texas)

- Year opened: 2009

- Total cost: $1.2 billion

- Public funding: $444 million

- Portion publicly funded: 37%

- Tenants: Dallas Cowboys (NFL)

Jerry Jones has a net worth of more than $9 billion, which includes the $5.7 billion value of his Cowboys, the world’s most valuable sports team. Yet, despite his personal wealth, the popularity of the team allowed the controversial Cowboys owner to convince Arlington, Texas, residents to vote in favor of ponying up more than a third of the cost of the $1.2 billion Cowboys stadium in 2004. Their share comes from a half-cent sales tax and hotel and car rental taxes. Jones outspent stadium opponents by a 100-to-1 margin ($5 million versus $50,000), and the measure won by a margin of 55% to 45%. Money talks.

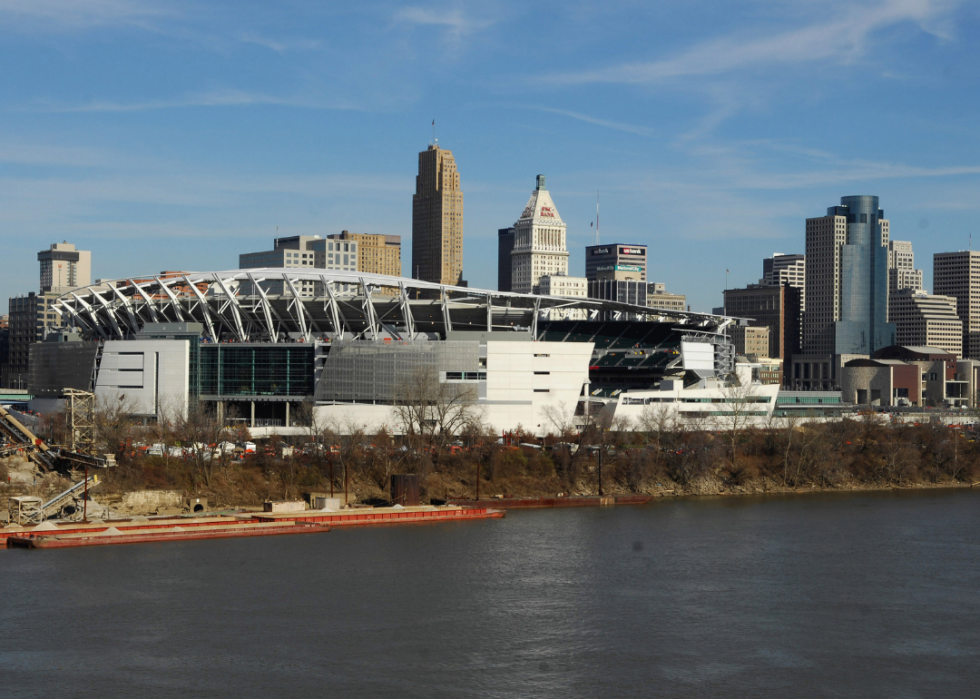

Paul Brown Stadium (Cincinnati)

- Year opened: 2000

- Total cost: $455 million

- Public funding: $411 million

- Portion publicly funded: 90%

- Tenants: Cincinnati Bengals (NFL)

Cincinnati residents can take some credit—nearly a half-billion dollars worth of credit, to be precise—for the Bengals’ 2022 Super Bowl appearance. The public paid for almost the entire riverfront stadium. But there’s already talk of it being outdated and in need of replacement before too long. The anxiety is well-placed as small-market teams like the Bengals that don’t have glitzy new stadiums are perennially threatened with extinction. Just ask any Oakland Raiders, San Diego Chargers, or St. Louis Rams fan.

Amway Center (Orlando, Florida)

- Year opened: 2010

- Total cost: $480 million

- Public funding: $420 million

- Portion publicly funded: 88%

- Tenants: Orlando Magic (NBA)

Many residents in the Disney-dominated city of Orlando, Florida, thought that paying for nearly half the cost of the Magic’s arena was a bit goofy or even daffy. But they were outnumbered by locals who convinced the city council that the arena would be a beauty, not a beast, and worthy of paying for most of it from hotel surcharges. So, yes, the next time you’re wondering about that hefty hotel tab when you take the kids to Disney World, you’re paying for the 20,000-seat arena. Average game attendance is north of 17,000, so the Disney magic (Disney is the team’s #1 sponsor) has made dreams come true for the Magic.

US Bank Stadium (Minneapolis)

- Year opened: 2016

- Total cost: $1.1 billion

- Public funding: $498 million

- Portion publicly funded: 45%

- Tenants: Minnesota Vikings (NFL)

When the Minnesota Twins demolished the old Metrodome to make room for a new outdoor stadium on the same site, prompted partly by ceaseless problems with the old roof, the writing was on the wall for the team they had shared ground with. The Vikings needed a new, football-friendly stadium. But who would pay for it? The Minnesota State Legislature decided that state residents would pick up much of the tab, tapping gambling, cigarette, sales, and corporate taxes. A Minneapolis hospitality tax also covered a portion of the cost.

Globe Life Field (Arlington, Texas)

- Year opened: 2020

- Total cost: $1.2 billion

- Public funding: $500 million

- Portion publicly funded: 42%

- Tenants: Texas Rangers (MLB)

The newest MLB ballpark is a state-of-the-art gem that cost about the same amount as the Cowboys’ nearby AT&T Stadium. Similar to that stadium’s funding, Arlington, Texas, is pitching in more than one-third of the cost, in this case, through a half-cent sales tax, 2% hotel surcharge, and 5% rental car tax. The cost is so high partly because of the retractable roof, which is used often during the dog days of Texas heat spells; it’s the largest single-panel retractable roof in the world. In Texas, they love to make ’em big.

LoanDepot Park (Miami)

- Year opened: 2012

- Total cost: $634 million

- Public funding: $510 million

- Portion publicly funded: 80%

- Tenants: Miami Marlins (MLB)

Is it ironic or just appropriate that a lending company has its name on this stadium? Because some pretty hefty loans came into play in its financing, including the biggest one from Miami and Miami-Dade County politicians, who put taxpayers on the hook for a cool half-billion. Because it’s spread out over 40 years, the total with interest is projected to exceed $2 billion. All for a team that routinely draws the worst- or second-worst crowds in the league—and for a stadium that taxpayers will be paying for long after it’s replaced by an even pricier one.

Barclays Center (New York)

- Year opened: 2012

- Total cost: $1 billion

- Public funding: $511 million

- Portion publicly funded: 51%

- Tenants: Brooklyn Nets (NBA)/New York Liberty (WNBA)

Many New Yorkers think the Nets overpaid for its superstars (especially the one who only played road games in 2021). But their salaries pale in comparison with what New Yorkers paid for the Nets’ arena. According to The New York Times, New York’s city and state governments chipped in about $260 million in taxpayer money and allowed another $266 million in tax exemptions. You can decide whether that was a three-point swish or a blown layup.

Nationals Park (Washington D.C.)

- Year opened: 2008

- Total cost: $611 million

- Public funding: $611 million

- Portion publicly funded: 100%

- Tenants: Washington Nationals (MLB)

It’s fitting that in the nation’s capital, the MLB ballpark was built not with some mixture of public and private funding but with all funding coming from the public. While the $611 million price tag is modest compared to today’s typical $1 billion-plus price tag, it’s still a lot of loot to pay for grass, seats, lights, and scoreboards. Business taxes, games ticket taxes, stadium merchandise sales, and rent paid by the team are the funding sources used to cover the bond.

Lucas Oil Stadium (Indianapolis)

- Year opened: 2008

- Total cost: $720 million

- Public funding: $620 million

- Portion publicly funded: 86%

- Tenants: Indianapolis Colts (NFL)

Lucas Oil would seem to be a better fit as the naming-rights sponsor of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, the best-known sports venue in Indianapolis, but a lot more money was needed for the Colts' stadium. The famed auto track only cost about $90 million in today's dollars ($3 million when it was built in 1909), only one-eighth the cost of the Colts' stadium. And the Colts only have to pay one-seventh of the stadium's cost, with the remainder covered by local sales, income, food, beverage, and car rental taxes and game ticket fees. The public funding was the most for any stadium at the time.

Allegiant Stadium (Paradise, Nevada)

- Year opened: 2020

- Total cost: $1.9 billion

- Public funding: $750 million

- Portion publicly funded: 39%

- Tenants: Las Vegas Raiders (NFL)

Vegas is all about money, and it cost a staggering amount to finance its gleaming new football stadium near the Strip. But, intent on adding one more attraction to lure visitors to come and spend their money—whether on slots, sports bets, or luxury suites—team owner Mark Davis forged a deal that had locals plopping $750 million in the pot. Time will tell whether the bet will pay off, but Vegas veterans will tell you that you can’t win if you aren’t in the game, and Vegas is now a proud NFL city. The public’s share of the stadium costs come from hotel room taxes backed by public bonds, though Clark County had to dip into its reserves to help the team get through the fan-free, COVID-19 pandemic period.

Yankee Stadium (New York)

- Year opened: 2009

- Total cost: $2.3 billion

- Public funding: $1.2 billion

- Portion publicly funded: 52%

- Tenants: New York Yankees (MLB)

“Damn Yankees!” is a 1955 movie classic but also the curse directed at the team everyone loves to hate when it came out that taxpayers would foot more than half of the mind-boggling $2.3 billion costs of its current stadium. The same team that hands huge contracts to free agents every year in its quest to add to its record 27 world championships pleaded poverty when it came time to build. So more than half of the construction costs came from public funds and tax breaks. A consolation to Yankees haters is that the team hasn’t gone to the World Series since the year the stadium opened.