Amelia Earhart: The life story you may not know

When it comes to daring American historical figures, pilot Amelia Earhart regularly ranks at the top of the list. A pioneering force for women in aviation, Earhart shot to fame in 1928 after becoming the first woman to fly across the Atlantic. She continued to break a slew of records in the aviation industry, becoming a celebrity in her own right. Earhart's ambitious career led her to attempt a round-the-world flight in 1937, and her subsequent disappearance has become the subject of much debate ever since.

Believe it or not, it's not just cultural speculation about where Earhart ended up that has carried on into the 21st century—actual search efforts remain underway. In July 2025, researchers announced that they may have located the remains of Earhart's plane on the tiny Pacific Island of Nikumaroro. Subsequently, Purdue University—where the pilot worked from 1935 until she disappeared in 1937—stated that it would send a team to attempt to collect the wreckage in November 2025, though that mission has been postponed to some time in 2026. President Donald Trump also ordered the full declassification of all records pertaining to Earhart in September 2025, and as of February 2026, several thousand pages worth of information have been released to the public via the federally run National Archives website.

While it remains to be seen whether the files or the Purdue expedition will provide anything that could help solve her disappearance, Earhart's story is so much more than its beginning or its untimely ending. To commemorate her prolific life and legacy, Stacker compiled a list of 25 facts from her life that you may not know. To do so, we consulted biographies, magazine accounts, museum records, news articles, and more.

While she's best known for her historic aviation feats, Earhart was much more than just a pilot. She was first thrilled with the idea of flying while working as a nurse during World War I. After becoming an overnight celebrity, she went on to mentor women in aviation, write bestselling books about her adventures, and become a close confidante of Eleanor Roosevelt.

Although she was lost to the world before her 40th birthday, Earhart's legacy of perseverance has established her as one of the most legendary aviators and an image of American courage to this day. Read on to learn more about her

1897: Born in Kansas

Amelia Mary Earhart was born to Amy and Edwin Stanton Earhart in Atchison, Kansas. She and younger sister Muriel were partially raised by their maternal grandparents, spending the school year in Atchison and summers with their parents in Kansas City. A tomboy, Earhart spent her early years outdoors hunting and sledding alongside Muriel. Due to Edwin's legal work with numerous railroads, the family eventually moved later in her childhood, also living in Des Moines, Iowa, St. Paul, Minnesota, and Chicago.

1908: First airplane sighting

Earhart first laid eyes on an airplane while visiting the Iowa State Fair at age 10. Although her legacy is inextricably tied to flying, it wasn't love at first sight. "It was a thing of rusty wire and wood and looked not at all interesting," Earhart later recalled.

1910-1915: Family struggles

After her more idyllic early years, much of Earhart's childhood was marked by family struggles. Her father, Edwin, began struggling with alcoholism, causing him to lose his job and at one point check himself into a sanatorium. The family's travels often left them on unsteady ground, living in unheated rooms or even camping. Earhart was also rocked by the loss of her maternal grandmother, Millie, in 1911. Eventually, her mother, Amy, left Edwin and moved with her daughters to Chicago. The two later reconciled.

1918: Served as a nurse during World War I

During World War I, Earhart decided to leave her studies at Philadelphia's Ogontz School in order to join the World War I effort in Toronto. In February 1918, she moved to the city and became a Voluntary Aid Detachment nurse at Spadina Military Convalescent Hospital. During this time, Earhart also caught pneumonia from one of her patients, and her lungs never fully recovered.

While in Toronto, she and her sister, Muriel, became acquainted with local Royal Flying Corps officers, often visiting nearby military airfields to watch pilots practice. "They were terribly young, those air men, and eager. … Aviation … inevitably attracted the romanticists," Earhart later wrote in her book "20 Hrs., 40 Min."

1920: First airplane flight

In 1920, Earhart attended an air show in Long Beach, California, with her father. There, pilot Frank Hawk took her on her first airplane ride, which proved to be a life-altering experience. "By the time I had got two or three hundred feet off the ground, I knew how to fly," she later recalled.

1921: First flying lesson

Following her first airplane ride, Earhart became determined to fly, taking up truck driving and working for a telephone company to earn $1,000 for lessons. Her first teacher was Anita "Neta" Snook, as Earhart had insisted that she must be taught by a female pilot. For her 25th birthday and with the financial help of her mother and sister, she bought her first airplane, a yellow Kinner Airster she named "The Canary."

October 1922: Set a world altitude record for female pilots

It didn't take long for Earhart to begin setting aviation records. Just a year after she began flying, she participated in an air meet at Los Angeles' Rogers Air Field. There, she set the women's altitude record by flying to 14,000 feet.

1923: Received her international pilot's license

At the time, Earhart was only the 16th woman to ever receive an international pilot's license. Around this time, she also received a flying certificate from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. While licenses weren't required, the certificate was necessary for pilots hoping to break current FAI records.

1924: Hiatus from aviation

For a time, Earhart put her aviation ambitions on the back burner to attend to family troubles. She sold her plane to help with struggling family finances, and following her parents' divorce, moved in with her mother and sister in Massachusetts. After a brief stint at Columbia University, Earhart took a series of jobs, from teaching English to serving as a social worker. Still, she joined the Boston chapter of the National Aeronautic Association and still managed to fly occasionally.

1924: Engagement to Samuel Chapman

Earhart met her first fiancé, an engineer five years her senior named Samuel Chapman, while he was boarding with her family. According to biographer Susan Butler, the two bonded over their love of tennis and philosophy. Before Chapman left the family for California in 1924, he asked Earhart to marry him and she accepted. The two's relationship lasted six more years before she broke off the engagement amid her burgeoning aviation success.

June 1928: Flew across the Atlantic

Earhart's life changed suddenly when publisher George Putnam tapped her to be the first woman to fly across the Atlantic by plane—albeit as a passenger. Traveling with pilot Wilmer Stultz and Louis "Slim" Gordon, the three arrived in Wales after around 20 hours in the air. Although crowds hailed her as "Lady Lindy," Earhart insisted she had been "just a sack of potatoes."

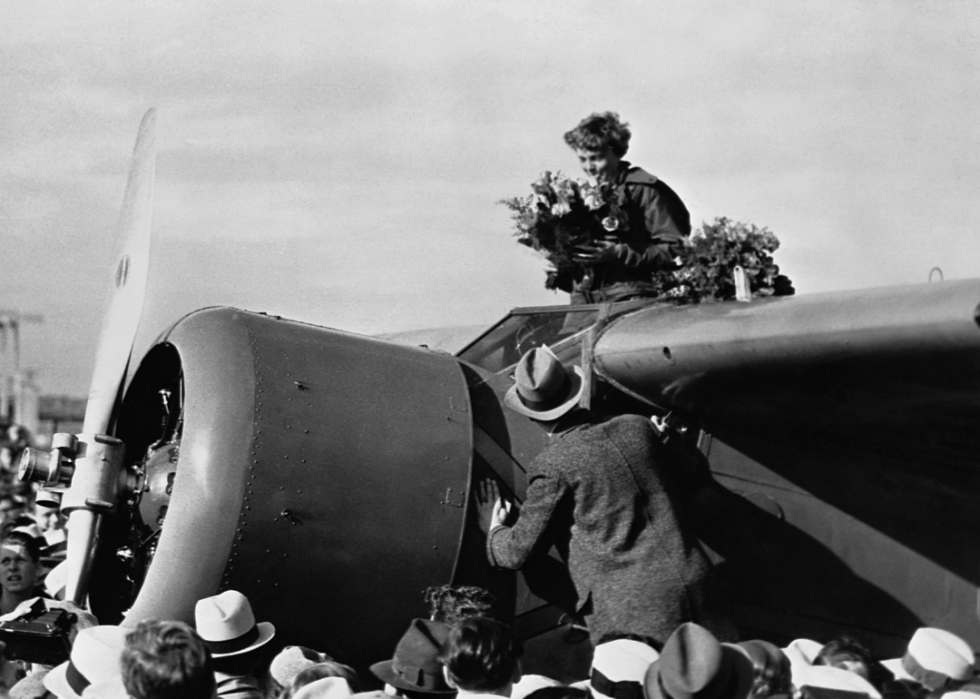

Summer 1928: Overnight fame

Following her trip across the Atlantic, Earhart became an overnight celebrity. Upon returning to the United States, she and her crewmates were invited to a White House reception hosted by President Calvin Coolidge. From there, she got a book deal, accepted a job as aviation editor for Cosmopolitan Magazine, endorsed products like Lucky Strike cigarettes, and went on a lecture tour.

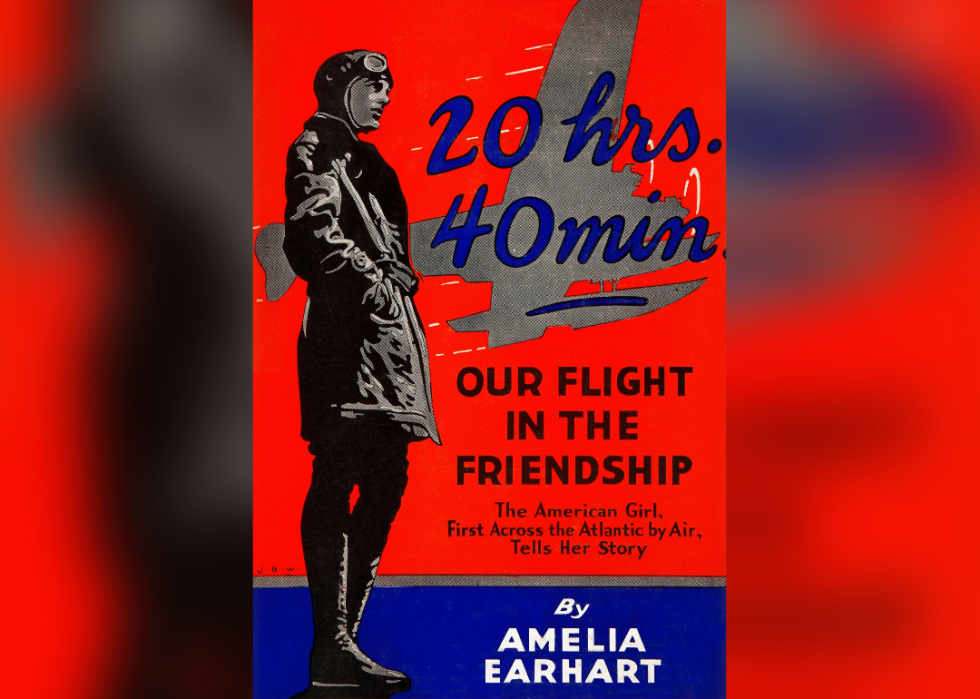

Summer 1928: Published first book, '20 Hrs., 40 Min.'

Capitalizing on her newfound popularity, Earhart published her first book, "20 Hrs., 40 Min." In the book, she writes about her historic experience crossing the Atlantic Ocean for the first time. However, she also included log entries from the flight, as well as passages recalling how she first became passionate about flying.

1929: Co-founded the Ninety-Nines

Meeting with a group of other women on Long Island, Earhart co-founded the Ninety-Nines, the first organization for female aviators. The name came from the fact that there were 99 charter members out of 117 licensed female pilots working in the United States at the time. Earhart was elected the group's first president, a position she held until 1933.

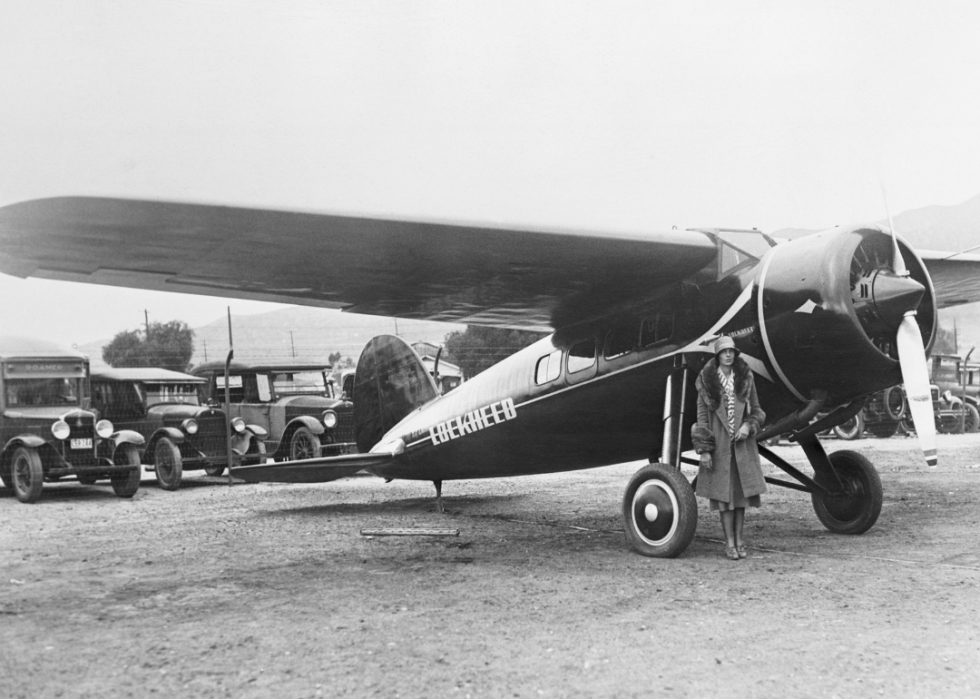

July 1930: Set the women's flying speed record

Earhart set the women's world flying speed record at 181.18 miles per hour. That same year, she became vice president of the airline Ludington Lines and received her transport pilot's license. However, tragedy also struck the Earhart family, as her father died of cancer around that time.

February 1931: Marriage to George Putnam

In February 1931, Earhart married Putnam, who was 10 years her senior. The two first connected while he helped her on her book "20 Hrs., 40 Min." Earhart held very progressive beliefs about marriage for the time, rejecting six proposals before finally accepting and writing to him on her wedding day: "In our life together I shall not hold you to any medieval code of faithfulness to me, nor shall I consider myself bound to you similarly."

May 1932: First solo female flight across the Atlantic

Four years after first crossing the Atlantic as a passenger, Earhart made history by flying the Atlantic on her own. In doing so, she became the first woman, and second person (after Charles Lindbergh in 1927), to accomplish such a feat. Upon returning home, she received a slew of honors, such as the Gold Medal of the National Geographic Society and the Army Air Corps Distinguished Flying Cross.

August 1932: First woman to fly coast-to-coast

Following her transatlantic flight, Earhart set another first-time record of her own. In August of 1932, she became the first woman to fly solo across North America and back. She completed the journey in a Model 5B Vega, a single-engine plane she customized herself.

1932: Published autobiography, 'The Fun of It'

When Earhart was asked why she flew planes, she often replied, "For the fun of it." Naturally, that became the title of her second book. While "The Fun of It" largely functions as an autobiography, she also spends time profiling other major figures in female aviation. Her next and final book, "Last Flight," would be published posthumously in 1937.

1933: Friendship with Eleanor Roosevelt

Upon another visit to the White House, Earhart struck a fast friendship with then-first lady Eleanor Roosevelt. During a White House dinner that year, Earhart spontaneously suggested that the pair take a brief flight to Baltimore before dessert. Later, Earhart even inspired Roosevelt to get her own student pilot's license.

January 1935: Solo flight from Hawaii to California

In January 1935, Earhart became the first person to fly solo from Honolulu to Oakland, California. That same year, she also made headlines by flying from Mexico City to New York and from Los Angeles to Mexico City. Around this time, she also joined the teaching faculty at Purdue University as a career counselor for women and an adviser to the school's aeronautics department.

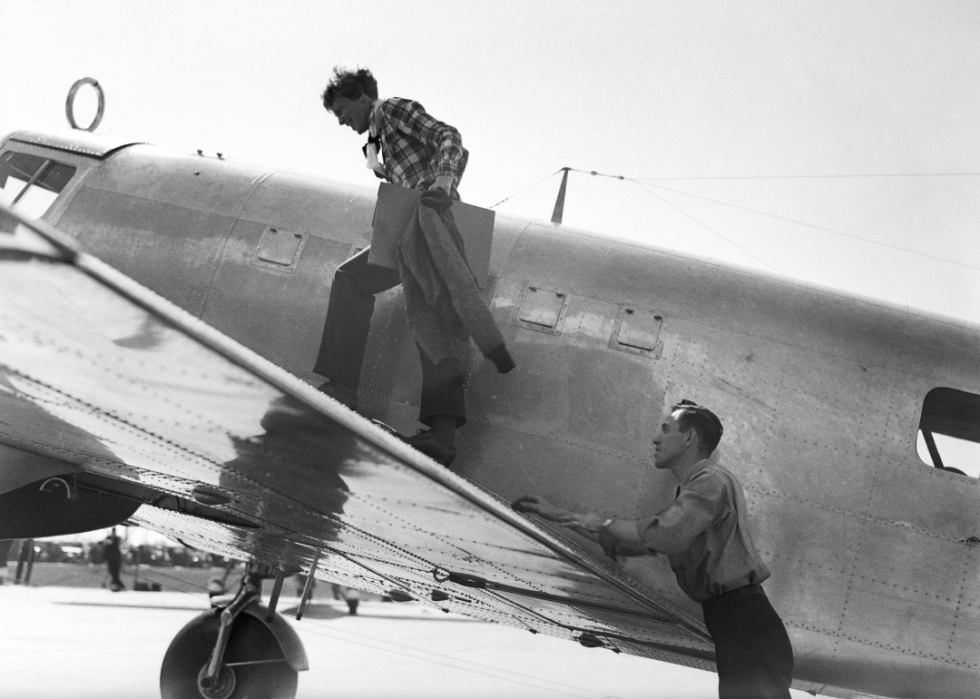

March 1937: First round-the-world flight attempt

After years of setting aviation records, Earhart decided to plan her most ambitious adventure yet: flying around the world. She made her first attempt in March 1937, intending to set off from Oakland, California, to Hawaii. Unfortunately, her plane was damaged upon a takeoff attempt and had to be returned to California for repairs.

June 1937: Second round-the-world flight attempt

Just a few months after her first round-the-world flight attempt, Earhart set off once again. This time, she was joined by Fred Noonan, and the pair were flying west to east. They departed from Miami but would never make it home to the United States again.

July 1937: Disappearance mid-flight

On July 2, 1937, Earhart and Noonan experienced weather difficulties and lost radio contact with the U.S. Coast Guard. Although an intensive search was authorized by both the U.S. government and George Putnam, their plane and remains were never found. The official explanation for Earhart's disappearance was that, due to running out of fuel, she crashed and sank northwest of Howland Island in the Pacific Ocean. However, some conspiracy theorists still hypothesize that Earhart secretly returned to the U.S. and lived as a housewife or that she was on a mission to spy on Japanese forces at the time of her death.

January 1939: Declared legally dead

Nearly two years after her disappearance, Earhart was declared legally dead in a Los Angeles Superior Court. To this day, what exactly happened to her and Noonan remains a mystery. Earhart continued to receive numerous honors after her death. She was posthumously inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1968 and the National Women's Hall of Fame in 1973.