Beyond Tulsa: Uncovering America's forgotten Black Wall Streets and their legacies today

Beyond Tulsa: Uncovering America's forgotten Black Wall Streets and their legacies today

"Beautiful, bustling, and Black"—that was how author, attorney, and activist Hannibal B. Johnson described Tulsa, Oklahoma's Greenwood District in his book "Black Wall Street: From Riot to Renaissance in Tulsa's Historic Greenwood District."

In the early 1900s, the Greenwood District flourished with over 100 Black-owned businesses, from restaurants and grocery stores to hotels and hospitals. Brick office buildings lined the streets with Black doctors, lawyers, and dentists ready to serve their communities. Visitors to the area included agricultural scientist George Washington Carver, famed contralto Marian Anderson, and blues singer and pianist Dinah Washington. The district's success represented more than just commerce; it embodied Black Americans' resilience and ingenuity in creating economic opportunities despite the crushing restrictions of Jim Crow laws.

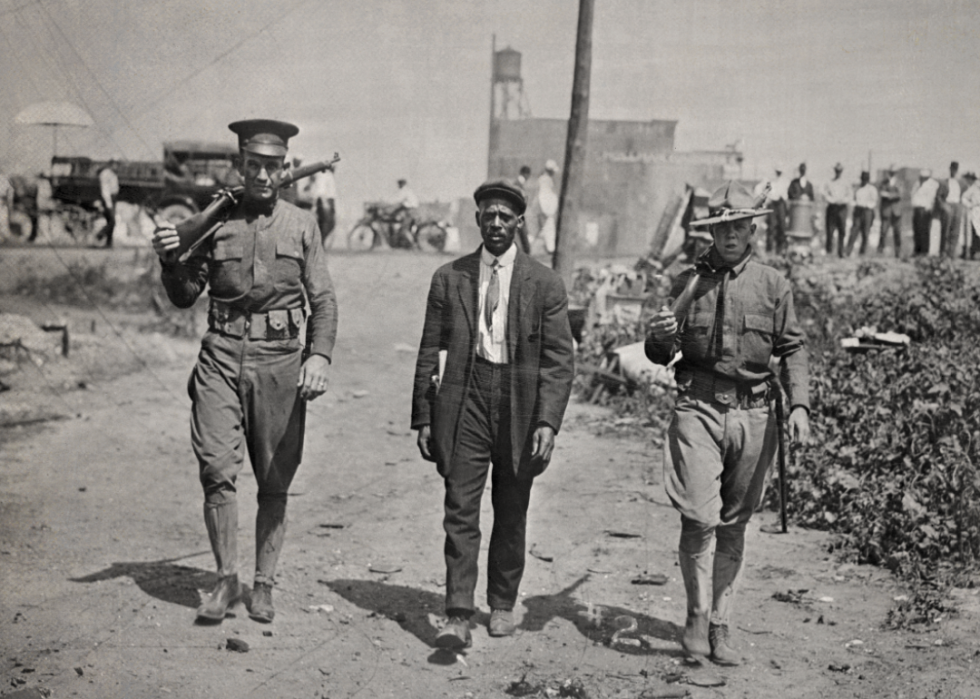

Greenwood's prosperity came to a violent end in 1921 when a white mob destroyed the district in what is now known as the Tulsa Race Massacre. In just two days, their ensuing violence left 35 city blocks decimated, over 800 people injured, potentially 100 to 300 people killed (though exact figures can never be determined), and generations of accumulated wealth erased.

Unfortunately, the tragedy at Greenwood wasn't an isolated event. The years leading up to 1921 were marked by race-related violence. As Johnson noted in his book, the United States saw 61 recorded lynchings of Black Americans in 1920; the year prior, more than 25 major race riots erupted throughout the nation in what was dubbed the Red Summer.

The devastation and its lasting impact

Today, the country continues to grapple with the aftermath of such vehement destruction. Evanston, Illinois, and Asheville, North Carolina, are among the few cities carrying out reparations projects despite opposition from the 6% and 13% of respondents who argued such programs would be too expensive or too difficult to administer, respectively, according to a poll of 1,000 people by the University of Massachusetts Amherst and Boston TV station WCVB.

Though Greenwood residents reconstructed with astonishing speed after the massacre, their efforts were continually stymied—not just by violence but by policies that deprived these areas of further opportunities. "The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre temporarily stilled the economic engines that revved on Black Wall Street. That said, the community quickly rebounded and rebuilt, peaking economically in the 1940s," Johnson told Stacker in an email. "In the 1960s and subsequent decades, structural factors like integration and urban renewal precipitated a second decline."

The 2024 ruling denying reparations to the last survivors of the massacre serves as a sobering reminder that the consequences of this destruction continue to reverberate through time, contributing to today's racial wealth gap.

The legacy of Black business districts across America

Though perhaps the most widely known, Tulsa's story was not unique.

"Wherever you had large Black populations concentrated because of segregation, you had these enterprising African Americans who sprouted up to provide every need possible," Dr. Shennette Garrett-Scott, author of "Banking on Freedom: Black Women in U.S. Finance Before the New Deal" and associate professor of history and Africana studies at Tulane University, told Stacker.

Across America, Black entrepreneurs established thriving business districts that faced similar threats from racial violence and discriminatory policies.

From Richmond's Jackson Ward—known as "the cradle of Black capitalism"—to Detroit's Paradise Valley, Chicago's Bronzeville, and Atlanta's Sweet Auburn, across America, Black entrepreneurs established communities with flourishing enterprises that stood as beacons of economic promise and prosperity.

Stacker used Census data and other sources to explore the untold history of lesser-known Black Wall Streets across the U.S. and how present-day Black business districts strive to rebuild wealth and opportunity in the current economic landscape.

The winding path to economic freedom

The roots of Black entrepreneurship run deep in American soil. The entrepreneurial spirit of Black Americans can be traced as early as the 17th century, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. Even while enslaved, Black Americans would barter and trade their surplus production with other people who were enslaved—though most profits went to their enslavers. Some with managerial duties even sold their skills and services to others. Once freed, Black Americans continued this tradition of engaging in businesses that used the skills valued by white enslavers, including catering and personal services such as tailoring and hair care.

In the decades following the Civil War, Black Americans faced a paradox: newly freed but systematically excluded from mainstream economic opportunities.

"These were enterprising, ambitious people who were trying to get their part, their piece of the American dream, who were just as enthralled with American free enterprise as their white counterparts," Garrett-Scott said. "Through their enterprise, they were able to carve out a space within the limitations—the limited options that they were given."

Overcoming systemic barriers

This exclusion, though devastating, sparked a wave of Black entrepreneurship across the country. According to the Negro Year Book of 1914-1915, Black business ownership grew from virtually zero in 1863 to over 40,000 enterprises by 1913, while Black homeownership rose from near zero to over 500,000 properties in the same period. This growth occurred despite the implementation of restrictive "Black codes" that required white sponsors for Black business licenses and Jim Crow laws that systematically segregated commerce.

These communities developed sophisticated financial networks, with Black-owned banks providing crucial capital to entrepreneurs routinely denied loans by white-owned institutions. "What made these Black business districts thrive wasn't just Black people supporting Black businesses; it was also Black-owned financial networks, Black banks, and Black insurance companies that provided the capital when white institutions refused," said Garrett-Scott.

One of the most significant developments was the creation of Black financial institutions. Exemplifying this trend was the Grand Fountain United Order of True Reformers, founded by Rev. William Washington Browne in 1881 in Richmond, Virginia's Jackson Ward. Beyond providing insurance and banking services, the True Reformers operated department stores, published a newspaper, maintained a home for older people, and invested in real estate across 10 Virginia cities, Washington state, Baltimore, and other locations.

Backlash and lasting impact

However, alongside these success stories came the backlash. Beyond Tulsa, Black Americans who engaged in economic activity fell victim to racial violence and intentional economic disruption. The East St. Louis Massacre of 1917, caused by white workers targeting their Black peers hired by the Aluminum Ore Company or the Elaine Massacre of Black sharecroppers seeking to unionize in 1919, marked systematic attempts to suppress Black economic independence.

"Violence plays a role in both creating Black Wall Streets and their decline," Garrett-Scott emphasized. "There are different, varying levels and kinds of violence." Beyond direct racial violence, Black businesses faced what Garrett-Scott calls "bureaucratic violence"—systematic exclusion from professional organizations, denial of licenses and permits, and restricted access to capital.

Discriminatory policies compounded the damage. Redlining prevented Black businesses from accessing loans and insurance, while urban renewal projects of the 1950s and 1960s often targeted Black business districts for demolition, displacing established enterprises and fragmenting communities.

"Urban renewal—ostensibly intended to eliminate urban blight—devastated Black Wall Street by displacing individuals and enterprises and gobbling up land," said Johnson. "Wealth disparities are in large part attributable to the ability to transfer property intergenerationally. Urban renewal adversely affected that dynamic for Black folks."

The ongoing wealth gap

The dismantling of these Black business districts has had lasting effects on economic progress for Black Americans spanning generations. According to the American Civil Liberties Union's 2023 Visualizing the Racial Wealth Gap report, the gap in wealth between Black and white families has only grown since the 1970s. In 2018, the median white family of three earned $33,000 more than a Black family of the same size. Black homeownership rates have also stagnated, lagging behind Hispanic homeownership rates and never reaching the 50% mark in the last 10 years.

"We haven't matched the level of economic destruction that came through those forms of violence and policy violence with the requisite level of economic investment into those communities. Each new generation can fall farther and far farther behind," Anthony Barr, director of research and impact at the National Bankers Association, told Stacker. Barr's research specializes in the racial wealth gap, financial wellness, and digitization.

Where Black Americans found success across the US

Different cities developed distinct patterns of Black business growth. Due to segregation, Richmond's Jackson Ward transformed from a mixed neighborhood that hosted German, Italian, and Jewish immigrants to a Black business hub.

During this time, "the Deuce," known as 2nd Street, became a cultural and economic powerhouse and the home of Hippodrome Theater, attracting performers like Nat King Cole and Cab Calloway. The district was also home to St. Luke Penny Savings Bank, founded in 1903 by the first Black American woman to charter a bank in the U.S., Maggie Lena Walker, and the Southern Aid and Insurance Company, the country's first Black life insurance company.

Durham, North Carolina, presented a unique case. Unlike older Southern cities, Durham's rapid growth as a tobacco town created unexpected opportunities. "My hunch is that the growth was so rapid that anybody could come here to get a job," Perry Pike of the Historic Preservation Society of Durham told the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. "They couldn't afford to discriminate in the way that other southern cities did." Durham was also believed to be more progressive than other communities.

"White allyship helped facilitate Black business success in Durham, both in terms of relative racial progressivism and capital investment," said Johnson.

Education and economic growth

This relative openness enabled the rise of North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company—the nation's largest Black-owned insurer at the time—and Mechanics and Farmers Bank. Andre Vann, a North Carolina Central University historian, also noted Durham fostered unusually progressive Black-white business relationships, with white capitalists often working through Black-owned banks to invest in Black communities.

Washington D.C.'s evolution tells yet another story. The city's Shaw neighborhood, particularly along U Street, emerged as a crucial hub after Black businessmen were forced out of downtown. By 1910, Shaw hosted over 200 Black-owned businesses, with the True Reformers' five-story building on 12th and U streets symbolizing the community's ambitions. The neighborhood's growth was closely tied to Howard University, reinforcing the power of education in economic mobility. The area's growth paralleled the expansion of Howard University, creating a symbiotic relationship between education and enterprise that became a model for other cities.

Barr notes modern Black business hubs can learn from these historical examples. "It's not just about creating new wealth; it's about supporting jobs, which is about supporting families," he said. "It's about increasing tax revenue, which is about being able to have more money available for public services and quality schools and infrastructure maintenance."

Collective economics: Building Black business districts today

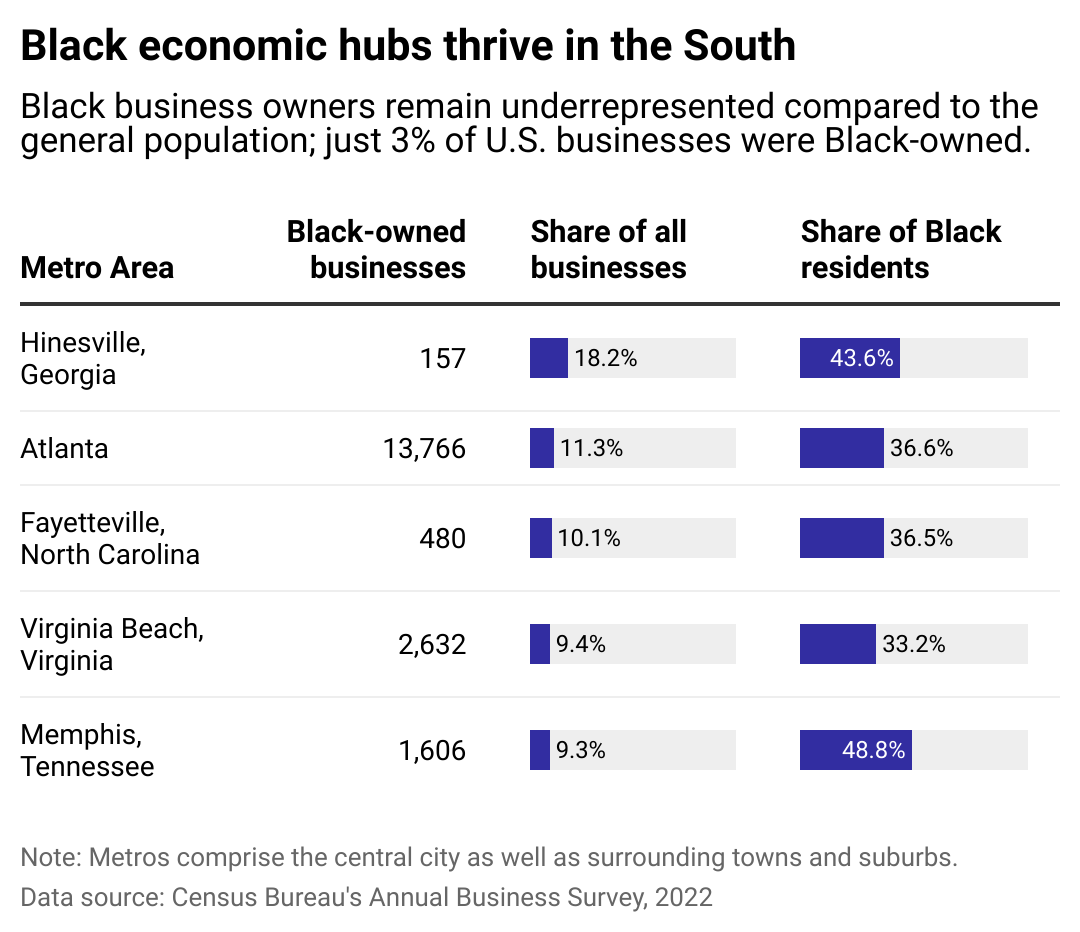

Today's landscape shows both progress and persistent challenges. Census data reveals that while Black Americans represented about 12% of the population, they owned just 2.4% of American small businesses in 2020. However, data suggests that Black-owned businesses thrive in Southern states. Hinesville, Georgia, leads with 18.2% of companies being Black-owned despite its population only being slightly above 35,000. On the other hand, Atlanta, a larger city with more than 500,000 residents, maintains a strong presence, with 13,766 Black-owned businesses representing 11.3% of all enterprises.

Cities like Memphis, Tennessee, also have a notable presence of Black businesses. The city, which hosts more than 600,000 residents, has a Black population comprising 48.8% of residents, and Black-owned companies comprise 9.3% of all enterprises.

The resurgence of modern Black business districts in these cities is driven by strong entrepreneurial ecosystems supporting emerging and established businesses. From local policies to entrepreneur networks, dedicated efforts are shaping sustainable ecosystems that empower Black entrepreneurs and fuel long-term success.

Building sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems

Today, this philosophy is embodied in the work of Atlanta's Dr. Lakeysha Hallmon, founder of The Village Market and author of "No One Is Self-Made: Build Your Village to Flourish in Business and Life." Hallmon launched The Village Market as a deliberate economic engine for Black-owned businesses. Since 2016, the model has served more than 1,440 businesses in 38 states and four countries, including the Bahamas. It has resulted in $8.8 million in direct sales to Black-owned enterprises and $800,000 in grants.

"The key for all of us is intentionality—whether through funding, mentorship, visibility, or policy changes, we must build ecosystems that not only provide opportunities but also advocate for long-term structural change in how Black businesses are supported and sustained. By working together, we can shift the narrative from survival to sustained success," Hallmon told Stacker in an email.

Mandy Bowman, founder and CEO of Official Black Wall Street, represents another example of the power of buying and supporting Black entrepreneurs. Bowman created Official Black Wall Street to connect Black businesses with consumers nationwide. Inspired by the history of Tulsa's Greenwood District, Bowman launched her platform to ensure Black businesses received sustained visibility and consumer support.

The power of social and economic networks

Ryan Wilson is the founder and CEO of The Gathering Spot, a private membership network designed to foster collaboration among Black professionals, entrepreneurs, and creatives. He underscores the importance of community spaces providing social and financial capital to help businesses thrive. "We have to have places where you're able to connect with the entire ecosystem. So, yes, business owners, but also the accountants, the lawyers, the people that can support your products," Wilson told Stacker.

Wilson emphasizes that business is ultimately built on relationships, and access to the right networks is often as crucial as access to funding. "At the end of the day, social capital is going to be required in order to facilitate financial capital and then ultimately close the wealth gap. People have to know one another before they do business with one another," Wilson said.

"Buying Black" has long been a powerful concept and driver of social capital in the fight for economic independence and wealth-building within Black communities. Johnson describes this tradition as "supporting Black-owned enterprises, entrepreneurs, and professionals; investing in our own community; and ownership—equity." Historically, Black business districts like Greenwood in Tulsa, Sweet Auburn in Atlanta, and Jackson Ward in Richmond were thriving because of "collective economics," or "economic cooperation" to support Black-owned businesses, ensuring that wealth circulated within Black communities.

And just as in centuries past with Black business districts, educational institutions like historically Black colleges and universities continue to be an economic mobilizer for Black entrepreneurship.

In Atlanta, the Center for Black Entrepreneurship aims to help bridge the wealth gap for Black communities through its programming and funding opportunities that serve Atlanta University Center students—which include Spelman College, Morehouse College, Morehouse School of Medicine, and Clark Atlanta University—and Black business owners. The center, bolstered by $10 million in funding from Bank of America, also provides a research program to find solutions for the unique challenges Black entrepreneurs face.

Challenges in accessing capital

Access to capital remains a significant barrier for Black entrepreneurs. According to the Federal Reserve's 2022 Small Business Credit Survey, Black-owned firms are twice as likely to be denied business loans as white-owned firms. The Census Bureau's 2022 Annual Business Survey also found that Black-owned firms were less likely to receive the full financing they sought than white-owned firms. Specifically, fewer than 2 in 5 (38.4%) Black-owned firms received all the funding they applied for, while 3 in 5 (62.3%) white-owned firms experienced the same outcome.

The venture capital landscape reflects similar disparities. In 2023, Black-founded startups in the U.S. received approximately $661 million in venture capital funding, representing just 0.48% of the total $136 billion allocated that year and 1.4% of total U.S. venture funding, TechCrunch reported. This marks a substantial decline from 2021, when Black founders secured nearly $5 billion, according to Crunchbase. The downturn of financing is more pronounced in certain regions. For instance, in Atlanta, Crunchbase reported investments in Black-owned startups dropped from $467 million in 2021 to just $23 million in 2023. However, some VC firms, such as the Atlanta-based Collab Capital, provide access to capital and strategic guidance to Black entrepreneurs and founders.

Broader economic disparities compound the financial challenges faced by Black entrepreneurs. A 2023 Pew Research Center survey found that 3 in 5 (64%) Black adults rate their personal financial situation as only fair or poor, and more than half experience at least one economic worry daily or almost daily. Despite these obstacles, entrepreneurship remains a key aspiration within Black communities; the same survey revealed that 22% of Black adults consider owning a business essential to their personal definition of financial success.

The Black Wall Street mindset and the future

These disparities underscore Black entrepreneurs' systemic and historical barriers to securing necessary funding for their businesses and achieving financial success.

While the challenges remain significant, today's Black entrepreneurs are building on their predecessors' legacy of resilience and innovation, working to close the racial wealth gap one business at a time.

"Black Wall Street clubs have sprung up all across the country," Johnson said. "They reflect what I call 'the Black Wall Street mindset,' the mental framework built on the historical example of the Black trailblazers from Tulsa's historic Greenwood District who displayed extraordinary vision, determination, and resilience in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds. Leveraging this powerful past, the Black Wall Street mindset says, essentially: 'They did. I can. I will.'"

Story editing by Carren Jao. Copy editing by Paris Close.