Students’ skills and interest in science tumble in first post-COVID-19 test

Students’ skills and interest in science tumble in first post-COVID-19 test

U.S. eighth graders are less prepared to be the scientists of tomorrow than they were before the pandemic.

In the first nationwide test of students’ science knowledge since 2019, the percentage of students scoring at the proficient level fell to 29%, down from 33%, and the average score dropped back to levels last seen in 2009, when a new version of the test was introduced, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

Students’ confidence in the subject area has also slipped, with 28% saying they “definitely can do various science-related activities,” down from 34%.

Performance fell across all three categories — physical, life, and earth and space sciences. Less than half of students can identify the major component of living cells, compared to 55% in 2019, and the percentage of students who can identify a characteristic of mammals declined from 72% to 68%.

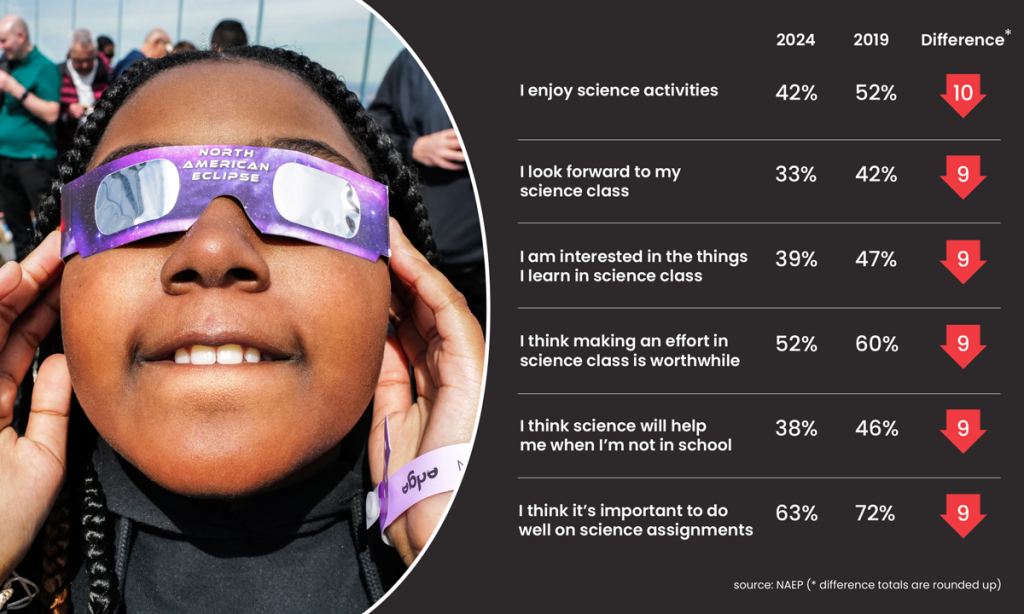

It’s not just the decline in skills that concerns science experts; it’s the dramatic decrease in their interest. The share of students saying they enjoy science activities plummeted from 52% to 42%.

“If you’re not interested, it’s hard to learn,” said Christine Cunningham, senior vice president of STEM learning at the Museum of Science in Boston and a member of the National Assessment Governing Board, which sets policy for NAEP. Students were also less likely than in 2019 to say they engage in tasks like designing research questions, debating scientific ideas and conducting experiments to explain why something happens. “As someone who works a lot with students or with teachers who do that kind of inquiry, that’s why students get excited,” Cunningham told The 74.

COVID-era school closures derailed student learning in all areas, but science was hit especially hard as teachers tried to keep kids on track in reading and math. A 2022 report from the Public Policy Institute of California showed that only about a quarter of districts emphasized science in their recovery efforts. Teachers were more likely to assign free online lessons and let students work at their own pace, compared with a typical school year. Widespread declines in reading performance have also hampered students’ ability to keep up in science at a time when technology is rapidly evolving.

“Science is such a hands-on experience, and trying to find ways to bring that to different homes was challenging,” said Autumn Rivera, a sixth grade science teacher in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, west of Denver. “Eleven- and 12-year-olds really need a lot of activity.”

She got families involved in “kitchen chemistry,” asked students to dissect a flower and recorded videos of lessons to discuss with students on Zoom. One of their favorite experiments was studying the water cycle by hanging a plastic bag full of water in a sunny window.

In the spring of 2021, according to assessment company NWEA, students had missed out on at least two months of science learning. By 2024, science achievement in third to fifth grade had returned to 2019 levels, but seventh and eighth graders, across all racial groups, saw the most significant declines and were still more than three months behind pre-pandemic performance.

One former education secretary warned against using COVID “as an excuse.” Margaret Spellings, who led the department during George W. Bush’s administration, noted that, as with students’ achievement in other subject areas, performance in science did not improve between 2015 and 2019. Average scores for eighth and 12th graders were flat and declined for fourth graders.

A positive trend, Cunningham said, is that more elementary schools have added STEM as part of an elective rotation with art and music. Those classes can be highly engaging, but aren’t always focused on grade-level standards, she said. In addition, regular classroom teachers might scale back science lessons and focus more on reading and math.

High and low performers

The declines in achievement were not confined to a few student groups. They affected students whether or not they live in the suburbs, come from wealthier homes or have parents who graduated from college. Students without disabilities and who speak English as a first language also scored lower than in 2019.

But Matt Soldner, acting NCES commissioner, pointed out what he considers the one encouraging sign from the results — a 6-point increase in scores for English learners.

“NAEP describes the what, not the why,” he said, “but that’s an interesting subgroup finding.”

As with other NAEP assessments, the science results show a widening gap between students scoring at the highest and lowest levels. Scores for students in the 90th percentile dropped from 196 to 194, but fell further, from 106 to 101, for students at the 10th percentile. In fact, for students at both the 10th and 25th percentiles, scores are at “historic lows,” said Soldner. “These results should galvanize all of us to take concerted focused action to accelerate student learning.”

Julia Rafal-Baer, co-founder of ILO Group, an education consulting firm, and also a member of the governing board, said access to books likely contributes to the disparities in scores. If science wasn’t a high priority in some schools, “how is it that high-performing kids are still absorbing enough to be able to be high-performing?” she asked.

Many students, Rivera said, lack the reading skills to interpret science texts.

“I’m having to take a step back and really focus on basic reading … which is not something that I am technically trained in as a sixth grade teacher,” she said. Like many teachers, she also sees families place less emphasis on consistent attendance and good work habits. “We’re seeing students missing work. We’re not really seeing … emphasis placed on school or on achievement.”

Poor basic math skills are also hindering students’ progress in science, said Cunningham, who designs STEM curriculum materials for schools across the country.

“Teachers are spending more time making sure that the kids are prepared to do some of the things that in the past they may have assumed kids would come equipped to do,” she said. “Could they make a table? Could they make a graph?”

On NAEP, the percentage of students saying they frequently “used tables or graphs to identify relationships between variables” fell from 43% to 39%. Less than a third “used math equations to explain or support scientific conclusions.”

‘Starving ourselves of knowledge’

NAEP will assess students’ reading and math skills again in 2026, but the next science assessment won’t take place until 2028, again just for eighth grade. Students will take a redesigned test that includes a stronger emphasis on students applying their knowledge and will incorporate more technology and engineering topics.

Because so many students — at least a third — score below basic, Cunningham added that the board felt it was important to expand the number of questions targeting students at that level.

“We need to know more about what that population knows,” she said. The questions, for example, might be simpler and require less reading.

Fourth graders were left out of the 2024 and 2028 science tests for budget reasons, Cunningham said. They’re scheduled to participate again in 2032. But one former governing board member said the absence of data from fourth graders is troubling.

“If there had to be a cut, I understand why we would, but it still raises the question of what we expect in science in early grades,” said Andrew Ho, a testing expert and education professor at Harvard University. “Why are we starving ourselves of knowledge about educational progress outside of [English language arts and math]?”

Staff cuts to NCES delayed the release of the results, which were expected earlier this summer.

During a background call with reporters last week, a member of the governing board said the results were “an opportunity for the field to see that these report cards are of the same quality that they have come to expect from the NAEP program.” But an NCES official on the same call said that in light of Education Secretary Linda McMahon firing most of the center’s employees, the department will need “sufficient staff and other resources in place” to conduct the tests next year and plan for 2028.

McMahon reiterated her support for the NAEP program during a recent interview.

“If we have an objective measure across all states, like NAEP, then I think that’s the best way to go,” she said. “We will not get away from having NAEP scores and the research that we can all rely on to make sure that we’re doing the right things.”

‘AI-driven world’

Beverly DeVore-Wedding, president of the National Science Teaching Association, still worries that the “current political climate” will diminish the program.

“I am concerned about them changing the assessment picture and that NAEP could get reduced to only reading and mathematics,” she said.

The science results also have implications for other aspects of President Donald Trump’s agenda, such as incorporating artificial intelligence into learning. Last week, first lady Melania Trump hosted an event tied to the president’s challenge for students to use AI to address community challenges.

“It’s not one of those things to be afraid of,” McMahon said at the event. “Let’s embrace it. Let’s develop AI-based solutions to real-world problems.”

Rafal-Baer said the rapid adoption of AI tools just reinforces the importance of science education.

“AI is here and it’s already reshaping how we work, learn and solve problems,” she said. “The complexity is only going to accelerate, and we can’t afford to have a scientifically illiterate workforce trying to navigate an AI-driven world.”

This story was produced by The 74 and reviewed and distributed by Stacker.