This story originally appeared on Hospice Care Ratings and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

The demand for end-of-life doulas is rising. Here's how they address the physical and emotional needs of those nearing death.

For 24 years, Natalie Ann Evans has worked as a birth doula, providing comfort and support to parents ushering new life into the world. But after caring for her mother in hospice in 2014, another facet of her career opened up.

"I realized how many similarities there were between end-of-life and [birth] doula work. So after [my mother] passed, I started supporting friends and family," Evans told Stacker.

A decade later, Evans decided to pursue end-of-life care and enrolled in a three-month end-of-life doula training program at the University of Vermont. Similar to a birth doula, an EOLD is a nonmedical professional who assists patients and families with the logistical, emotional, psychosocial, and spiritual aspects of dying. Death doulas, as they are sometimes called, are "companions to walk people through the process of dying," said Evans, adding that they give patients the "heart and hands, but also information that they need."

While there's currently no governing organization regulating end-of-life certifications, many doulas choose to get certified. In 2023, the International End-of-Life Doula Association boasted a membership of 1,500, compared to just 300 a few years prior.

The growing interest in and demand for trained individuals to help people transition at the end of life is partly due to what Evans considers an "opening up to accept and talk about what it means to die."

"You can have agency here," she told Stacker. "There's been a cultural shift of people being curious and wanting to know more."

And it's a shift decades in the making.

The growing death-positive movement

Many Americans grew up under the false assumption that talking about death was morbid, taboo, and simply inappropriate. However, since the 1960s, American culture has evolved in its approach to and acceptance of mortality, helping to normalize public discussion about death and dying. This is largely attributed to the introduction of hospice care to the United States in the 1970s. Hospice caregivers, like nurses, doctors, and social workers, support end-of-life care, focusing primarily on meeting medical needs and pain management. What began as a volunteer organization in the 1970s has evolved into a federally funded program integral to U.S. medical care.

The movement toward greater transparency around death and dying saw a marked shift in 2011 with several major initiatives. The late John Underwood created Death Cafe, a concept where people meet up in person or virtually to talk about death and grief to help reduce the stigma around these difficult conversations. That same year, end-of-life doulas, also known as death midwives, grew in popularity, and Washington state became the first state to legalize natural organic reduction burials.

This coincided with a budding community that grew into the death-positive movement, now an international phenomenon. It spawned, in part, from mortician Caitlin Doughty's nonprofit initiative, The Order of the Good Death, which aims to help change perceptions of funeral professionals, death, and dying—which was largely accomplished through her Ask a Mortician web series.

This trend has been most recently seen on DeathTok, where a group of real-life hospice workers, morticians, and death workers sing, dance, and improvise about their experiences on TikTok.

Talking candidly about a "good death"—one that is peaceful, meaningful, and in alignment with what the dying person wants and needs—has become more common for several reasons. During the COVID-19 pandemic, mortality was top of mind, and talking about death and dying was normalized. In the process, awareness grew about the gap in addressing the needs of the dying in an increasingly secular society.

Moreover, baby boomers—expected to comprise 22% of the U.S. population by 2040—are aging. By 2030, all boomers will be at least 65 or older; by 2040, about 78.3 million Americans will fall within that age bracket. That means more older adults will need care, and with grown children living further apart from their parents, some will turn to resources outside of the family unit for end-of-life care.

Hospice Care Ratings used KFF and National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization data to highlight hospice use and explain the important role EOLDs can play in helping people die more peacefully and with dignity.

As boomers age, more families are using hospice care

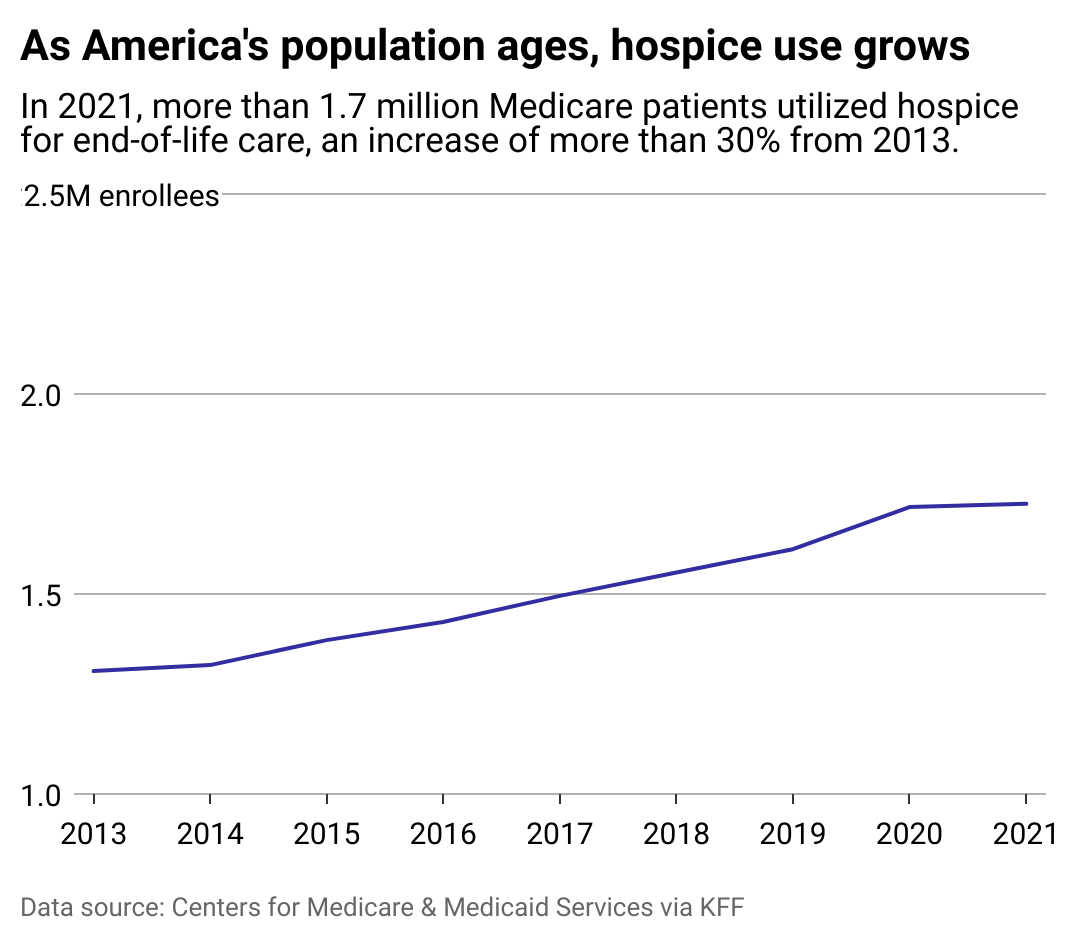

While EOLDs are still not mainstream, hospice care has evolved in the past two decades. The number of Medicaid beneficiaries who used hospice services rose by 30% between 2013 and 2021, according to KFF data. In 2021, 1.7 million Americans accessed hospice care from a pool of 2.6 million beneficiaries who died that year, meaning nearly 66% of patients chose to use hospice services.

Hospice services are palliative, meaning they focus on providing comfort and maintaining a patient's quality of life, not on curing a disease. Patients with a terminal prognosis (a life expectancy of six months or less) are eligible for Medicare hospice coverage, and some enter hospice in the very last weeks of life. The most common diagnoses of hospice patients are neurological diseases, such as Alzheimer's, along with cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and heart failure.

Medicare currently offers plans at varying care levels, from inpatient services to routine visits and continuous care, the latter two of which occur in the patient's home. Coverage at all levels includes symptom and pain management, medical supplies, and emotional support.

Visits from a hospice nurse can entail administering medications and monitoring a patient's physical well-being. Sometimes, hospice care includes social workers, chaplain services, and other community resources. They supplement, but do not replace, the role of a primary family caregiver. Even with a hospice team in place, many family caregivers lack the flexibility or experience required to care for a dying loved one.

The role of end-of-life doulas in hospice care

Many people need more consistent support between visits from hospice aides or even a knowledgeable presence or hand to hold—and that's where EOLDs like Evans come in. Death doulas often provide a bridge between hospice staff and families, helping to facilitate care.

"I will typically do a four- to six- or eight- to 10-hour shift, and I might be reading books and listening to music. I am a long, steady presence, which a hospice nurse can't do," Evans told Stacker.

As awareness grows about the needs of people nearing death, EOLDs are increasingly becoming an integral part of end-of-life services. They help with the emotional and logistical aspects of dying while hospice attends to medical needs. Just as it takes a village to raise a child, it takes one to help someone die ethically and peacefully in the manner that they want.

Evans described her job as having a holistic and practical side, but both involve figuring out what is good for people who are dying, not what they "should" be doing. When she meets with a new patient, she has a checklist: Do you have a will? An ethical will? A legacy project you want to undertake? Who can water your plants? These are the things that often fall through the cracks for families at a stressful time, even if they have the benefit of Medicare-covered hospice care.

Death doulas can also help set up essential documents like health care proxies and do-not-resuscitate orders. They also help facilitate difficult conversations, plan funeral arrangements, and provide support for grieving family members in the weeks and months after their loved one's passing. With EOLDs and hospice staff working in tandem, patients receive a more holistic approach to end-of-life care. This approach means thinking about every step of the process, from illness to health care choice and from how and where you die to how you are buried.

A patchwork health care system leads to disparate care

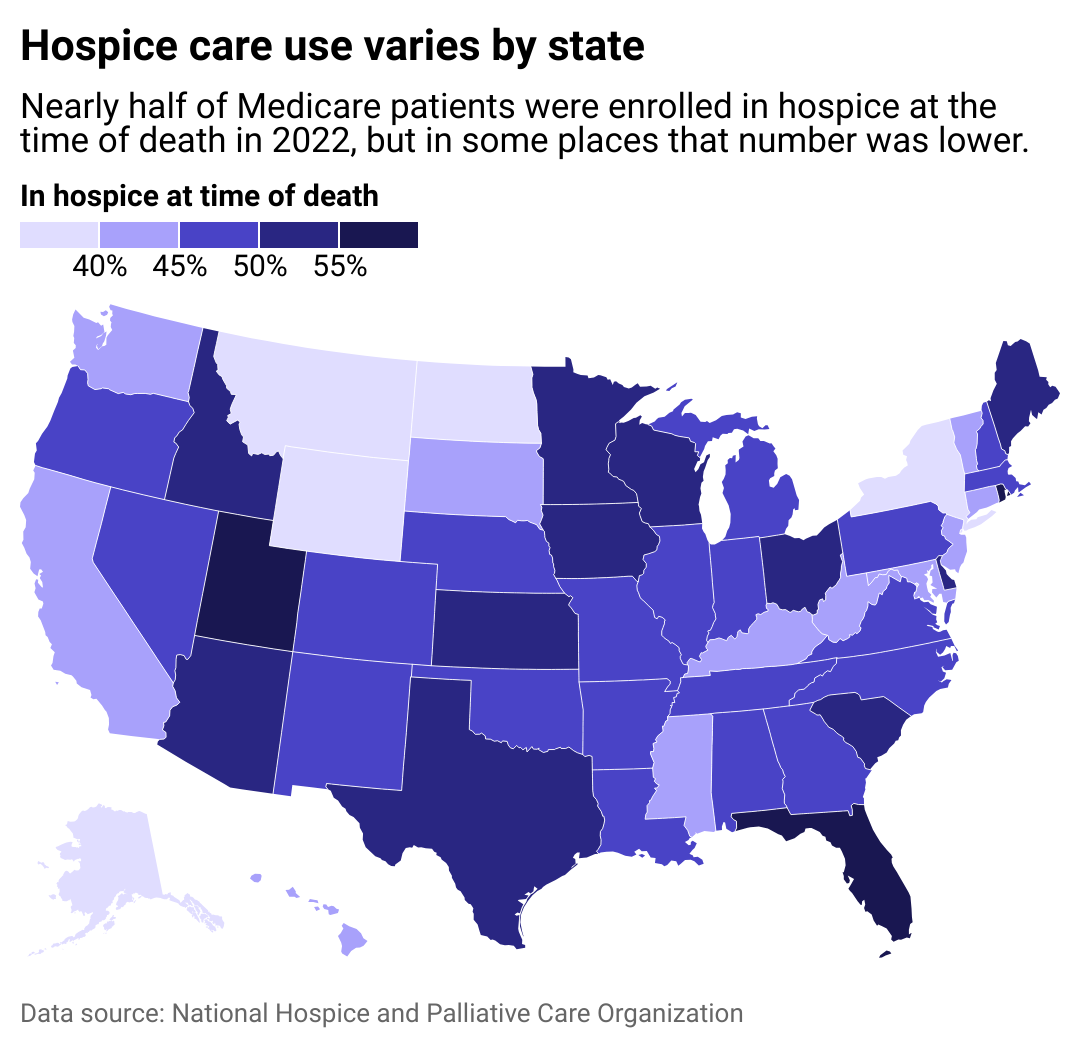

In 2022, nearly half of Medicare patients were enrolled in hospice at the time of their death, though figures vary from state to state. The increase in the use of hospice care services by older adults is a nationwide phenomenon, though usage varies widely.

Utah, Florida, and Rhode Island ranked first, second, and third, respectively, in the percentage of Medicaid beneficiaries who use hospice care benefits, which ranged between 55% and 60%. Meanwhile, New York had the lowest utilization rate at 25%, followed by Washington D.C., Arkansas, and North Dakota, with 40% or less of Medicare populations using their hospice benefits. This illustrates how disparate levels of care across the nation can lead to vastly different caretaking and end-of-life experiences.

The average length of stay in hospice is 92 days, and half of patients were enrolled for 17 days or less, but Medicare hospice coverage varies from state to state. For example, Alabama currently has the highest number of average hospice days covered by Medicaid at 91.3 days, while Wyoming ranks last with only 47.65, according to 2021 KFF data.

Disparities in hospice utilization across the nation

For those who don't qualify for Medicare and Medicaid coverage, private insurance, employment-based plans, and some long-term care insurance plans offer hospice coverage, typically with similar eligibility requirements as federal programs. However, about 8% of the U.S. population is uninsured, according to 2024 Census Bureau data.

This includes Americans stuck in the economic middle who do not qualify for federal assistance but don't have private insurance or the funds to cover additional medical expenses.

Nonprofit and specialty groups are filling some of the gaps and making coverage possible for more people. All enrolled veterans are eligible for hospice care through the Veterans Association; those with terminal cancer may qualify for additional services. Similarly, a plethora of free social services and resources are available for older adults through religious-affiliated organizations like The National Institute for Jewish Hospice and the Muslim Spiritual Care and Hospice Network, as well as many local Christian organizations.

Currently, Medicare does not cover EOLDs, but Evans believes the landscape may be shifting. She hopes that in a year or two, it might be standard practice to have death doulas covered by Medicare and Medicaid. Birth doulas, which weren't covered by insurance until recently, are now classified as a preventative service by Medicaid and eligible for reimbursement in a handful of states, including California, Oregon, Michigan, and New Jersey.

If the path of birth doulas sets a precedent, increasing the understanding of birth as a highly specific, holistic experience paved the way. As the population ages, hospice care use continues to rise. As more families grapple with loss, awareness and understanding about the emotional and spiritual needs of people who are dying and their loved ones will likely also expand—something Evans has long hoped for.

"My job is to listen to what people want," Evans said. "Dying is a personal experience."

Story editing by Alizah Salario. Copy editing by Janina Lawrence. Photo selection by Ania Antecka.