‘We opened a door nobody knew existed’: How displaced Black families won reparations in Portland

‘We opened a door nobody knew existed’: How displaced Black families won reparations in Portland

For decades, the Albina district in Portland, Oregon, was the center of the city’s Black community. Local musicians transformed the neighborhoods into a hotspot for the West Coast’s jazz, blues, and soul music scenes, earning Albina the nickname “Jumptown” in the 1940s and ‘50s. Milestones in Oregon’s civil rights struggle grew out of meetings in Albina’s parks and gathering halls. It was residents of Albina who started a citywide tree-planting program responsible for many of Portland’s now-famous blooming cherry trees.

But by the ‘70s, much of it was gone. Government officials had carved up the area in the name of urban renewal, displacing hundreds of Black families, Next City reports.

Cities nationwide have stories like Albina’s. But last month in Portland, community organizers helped write a new chapter, as the city became one of the first in the U.S. to resolve a legal claim holding public agencies accountable for the racist policies that displaced families decades ago. The settlement includes an $8.5 million payment to survivors and descendants, as well as other non-monetary support.

Even as the federal administration rolls back protections, the settlement sends a message about the power of community organizing and local elected officials to address racist harms, according to attorneys and plaintiffs.

“It’s important to [address] historical racist conduct, understand that it still lives and has impacts today, and that we can and should address it, regardless of what the federal government thinks,” says J. Ashlee Albies of Albies & Stark, an attorney for the plaintiffs.

Twenty-six individual survivors and descendants of families displaced from the historic Central Albina neighborhood filed the federal civil rights lawsuit against the City of Portland; The city’s development commission, called Portland Prosper; and a hospital involved in an old scheme to redevelop the neighborhood in December 2022. The Emanuel Displaced Persons Association 2 (EDPA2), an organization of survivors and descendants, was also a plaintiff.

The suit alleged that from the 1950s to the 1970s, the defendants conspired to force hundreds of families from their homes and businesses in Central Albina. Historically, Albina was home to 80% of Portland’s Black population.

Between 1971 and 1973, the City of Portland and Portland Prosper’s predecessor, the Portland Development Commission (PDC), demolished more than 180 properties in the neighborhood, including homes, businesses, and buildings belonging to church and community groups. Of those displaced, 74% were Black. Many were homeowners. Byrd, founder of EDPA2, calls the episode “a real estate massacre.”

At the time, the City of Portland and PDC claimed that properties in the neighborhood were blighted and used eminent domain to force some residents out of their homes. They claimed that the demolitions were necessary to expand Emanuel Hospital, now called Legacy Emanuel Hospital. However, the hospital expansion was never realized.

Decades later, much of the land seized from Black families in Central Albina remains vacant or is used only for parking. Survivors remember a different Central Albina. “It was a thriving Black neighborhood, a thriving community,” Donna Marshall, whose family was the last to leave the neighborhood in the 1970s, told Oregon Public Broadcasting.

Plaintiff Mike Hepburn’s grandparents, Donald and Elizabeth Hepburn, owned a duplex that had been in the family since the early 1900s. Above is a 1969 photo of the Hepburn family's house, which was demolished against the family’s will to expand Emanuel; below is a 2022 photo of the still-vacant lot where the Hepburns' house once sat.

For many families, the loss of homes in Central Albina meant a loss of community, inheritance, and access to education, employment, and other opportunities. “I lost all my friends. We lost our business,” recalls Marshall, who was a teenager when her family was forced to relocate. “Everything just fell apart.”

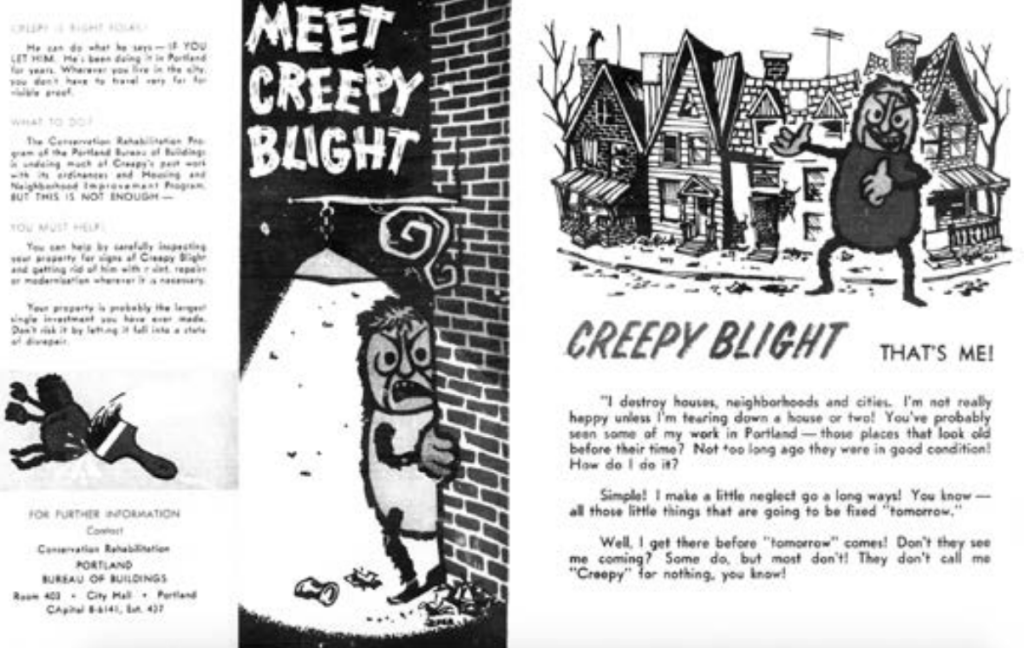

Byrd, a trained librarian turned community archivist, uncovered much about Central Albina’s past through painstaking research that laid the groundwork for the legal claim. “I did that through scouring Portland archives, old newspaper articles, talking to people, even looking at advertising, brochures, and obituaries,” she explains.

During her research, Byrd discovered something unexpected and personal about the destruction of Central Albina. “I saw my grandmother’s name in one of the documents that I came across,” she recalls. “I was like ‘Wait a minute, this is my grandmother,’ and then it was on because I really wanted to find out what had happened.” She also learned more about the original Emanuel Displaced Persons Association, an organizing group that gathered in a church basement and sought to prevent the removal of Black families from Central Albina decades earlier.

Later, EDPA2 partnered with graduate students at Portland State University, who mapped demolitions and calculated the value of lost wealth across the neighborhood. That report found that if displaced residents still owned their homes in Central Albina, they would “likely control close to $100 million in residential property wealth, excluding the value of [seized] commercial properties.” The report recommended that the City of Portland create a restitution task force to administer a repayment plan.

PSU’s research also revealed that Emanuel Hospital began purchasing properties scattered across Central Albina long before plans for an urban renewal project were approved or announced. The hospital allowed buildings it had bought to sit empty or demolished them, later contributing to claims of blight in the neighborhood. Once PDC approved an urban renewal project in Central Albina, it paid the hospital the purchase price of the properties that the hospital had acquired earlier, as well as demolition costs.

A 1962 brochure produced by the Portland Bureau of Buildings that promoted the notion of “blight” in Central Albina. (Image courtesy of the Oregon Law Center)

“The conclusion we drew from this history is that the hospital would never have spent all that time and money to purchase these randomly located properties if they didn’t have the assurance that the city and Prosper Portland were going to come in and finish the job,” Ed Johnson of Oregon Law Center, one of the attorneys for the plaintiffs, told Oregon Public Broadcasting.

Details of what plaintiffs allege was a conspiracy to forcibly displace Black residents of Central Albina enabled attorneys to craft a case seeking justice for survivors and descendants. “It was a challenging legal argument but a righteous one,” says Albies. “There had been apologies from these institutions, but no real restitution had been offered, and [the lawsuit] was an opportunity to really talk about the impact on these families.”

The recent settlement aims to compensate for some of the economic loss and non-economic harm that families displaced from Central Albina experienced. The agreement acknowledges “Portland’s systemic discrimination and displacement” of Black communities, including excluding them from homeownership and “perpetuating segregation, displacement, and harmful stereotypes.”

The defendants first agreed to pay $2 million to settle the case. However, the Portland City Council later voted unanimously to increase the settlement to $8.5 million, after considering testimony from survivors and descendants about how the city’s racist actions had affected them and their families.

“It was a remarkable and important experience to see City Council recognize the scope and depth of harm,” says Albies. “Even though that increase is not enough to fully provide restitution, it is an important moment because it shows what can happen when you elect leaders who are from the community, who understand the impact of the harm of past practices and attempt to address that.”

The settlement also includes turning over property to EDPA2, establishing a permanent exhibit space dedicated to commemorating the history of Central Albina and Portland’s Black community in Keller Auditorium, supporting a documentary film about the displacement, and proclaiming an annual Descendants’ Day in Portland.

While the case in Portland is unique because researchers uncovered what they believe is evidence of a conspiracy to demolish swathes of Central Albina and displace Black families, it offers lessons in the importance of community archiving and organizing.

Recent examples of historic restitution packages in Tulsa, Oklahoma, to address the harms of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, and Palm Springs, California, to compensate Black and Latinx families displaced in racist urban renewal schemes, also relied on organizing at the grassroots and bringing to light historical evidence of past harms.

Back in Portland, Albies and Byrd hope that the recent settlement is only the beginning. “Although it’s not perfect, and it’s not adequate, it’s still very significant,” says Byrd. “We opened a door that nobody even knew existed.”

This story was produced by Next City and reviewed and distributed by Stacker.