Trump administration declares timber emergency after decades of employment decline in the industry

Trump administration declares timber emergency after decades of employment decline in the industry

Earlier this year, the Trump administration issued an executive order to increase timber production by at least 25%, citing wildfire risk reduction and economic development as the primary drivers behind the order. Whether President Donald Trump’s forest management policies will improve rural economies in communities formerly dependent on logging is a point of contention, however.

The Daily Yonder reporters Sarah Melotte and Ilana Newman spent a week in mid-August interviewing sources for a series of articles about mining, natural resources, and human health in the rural Northwest. On their first day out in the field, they met logger Bruce Vincent, owner of Vincent Logging, at his office in the small town of Libby, Montana. Vincent Logging is a small timber operation that Bruce’s parents started in 1968.

They spent the majority of the day riding in Bruce’s truck, listening to him tell them about the history of natural resource extraction in Libby, his passion for creating a better place for the next generation of Montanans, and the many projects he takes on around town to help realize that vision. For fun, he said he has 20 grandkids, who tend to keep him busy. He smiled, his blue eyes squinting beneath an old baseball cap.

After lunch, Bruce took the reporters to an active logging area where his son, Chas Vincent, was operating a machine, aptly referred to as a delimber, that strips branches from felled trees. After delimbing the logs, Chas separated them into neat stacks by species.

Employment in the natural resource extraction industry, like logging and mining, used to be the primary driver of economic activity in many small Northwestern towns like Libby. But those jobs have dwindled in recent decades, leading to the socioeconomic challenges associated with unemployment, including low wages and high poverty. In 2023, Libby’s poverty rate was 26%, more than twice as high as the national rate of 11%.

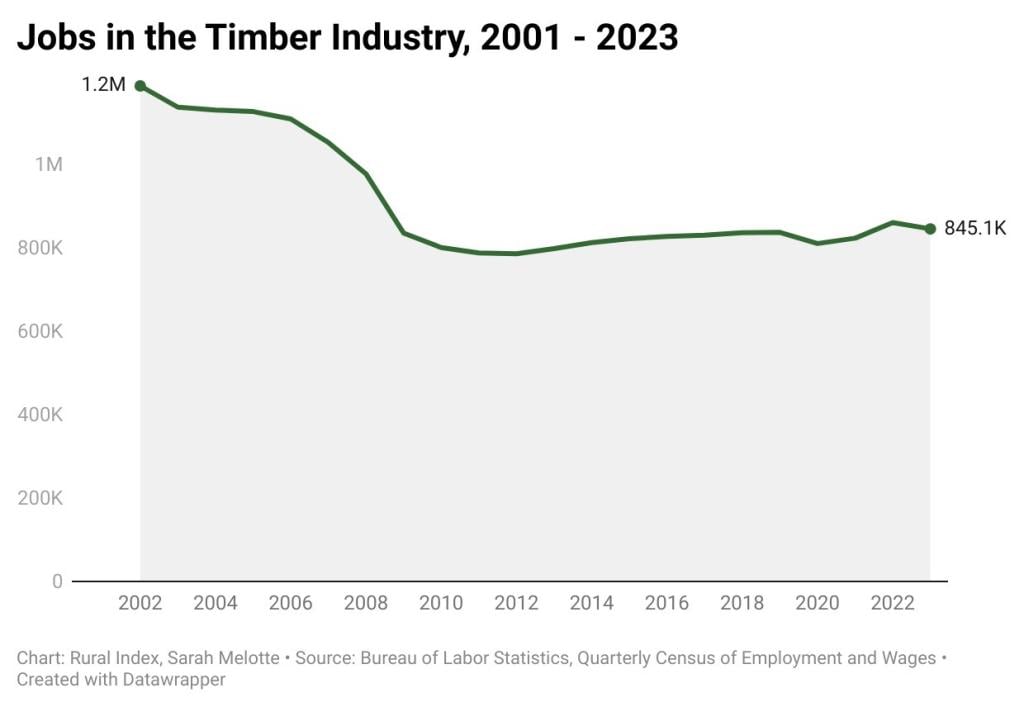

Timber jobs have been on the decline nationwide. Timber employment went from about 1.2 million jobs in fiscal year 2001 to about 845,100 jobs in 2023. In this analysis, timber jobs include employment related to the growing, harvesting, and transportation of trees.

This county-level data comes from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW), a Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) measure meant to capture economic changes over time. Timber went from about 1% of total employment in 2001 to 0.58% of employment in 2023, representing a decline of almost half a million jobs.

In contrast to most of Melotte’s other figures in the Rural Index, this analysis includes data from metropolitan counties. That’s because over 65% of timber industry jobs were in metro counties in 2023. Most of those jobs were likely within rural tracts of metropolitan counties, since logging requires wide swaths of forestland. But because the federal system Melotte usually uses to categorize rurality is a county-level binary, it doesn’t allow her to capture the nuances within an individual county. Including timber employment data of all counties, not just officially rural-categorized ones, lets her demonstrate the timber employment trends at a larger scale.

On April 4, 2025, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollins established an Emergency Situation Determination (ESD) that would expedite environmental permitting on 112.6 million acres of publicly held U.S. Forest System land. Rollins’s action came a month after Trump’s Executive Order to expand timber production by 25%. Enacting the ESD would allow the Forest Service to roll back environmental protections to expedite the logging process.

According to Rollins, issuing the ESD will clean out forests at high risk of wildfire and support rural economies, but experts say the truth is more complex than that.

Assistant Professor at Washington State University, Austin Himes, told Oregon Public Broadcasting (OPB) that Trump’s orders don’t address the main issues that led to timber decline. Himes said logging economies need a steady supply of timber over several decades, not a temporary jolt in production. But the Trump administration’s forestry plans don’t address sustainable long-term planning, according to Himes.

“What we’re going to see, I suspect, are areas that are hit particularly hard by very intensive harvesting practices that lead more to sort of lose-lose situations for communities who enjoy those forests and the ecological sustainability of those forests,” Himes told OPB.

But many industry experts and rural people disagree, saying that Rollins’s memorandum will ensure that forests are managed sustainably while growing rural economies by truncating environmental regulations like the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), believed by many in the timber industry as an unnecessary bureaucracy.

“By streamlining permitting and empowering forest managers, this initiative will create jobs, support rural economies, and ensure our forests are properly managed for future generations,” House Agriculture Committee Chairman Glenn Thompson told the American Ag Network, a multimedia news source.

But the national timber emergency declaration might not be legally viable, according to Albert C. Lin, professor of law at the University of California, Davis. In an article for the The Conversation, Lin said the Trump administration’s ESD doesn’t qualify as a legal emergency under the Army Corps of Engineers definition, which stipulates that a situation qualifies as an emergency if it results in “an unacceptable hazard to life, a significant loss of property, or an immediate, unforeseen, and significant economic hardship.”

According to a memorandum issued by the Army Corps of Engineers, an emergency situation can include natural disasters, like earthquakes and floods, or “catastrophic … failure to a facility,” like a collapsed bridge. The Trump administration’s ESD doesn’t qualify as an emergency under The Corps’s own guidance, Lin argued.

Bruce said there was more to a timber economy than just felling trees.

“You need a market to deliver the product to,” he said. “We used to have a sawmill in town. We had a plywood plant in town. We had a pres-to-log plant in town. We have none of that … so we need to have a small processing plant in town. And in order to get that, we’ve got to have this certainty that the forest is going to be managed.”

In May of this year, Bruce and Vincent Logging fostered a partnership between Lincoln County, Montana, where Libby is the county seat, and the U.S. Forest Service to manage forest lands with the twin goals of economic development and wildfire risk reduction. Lincoln County is surrounded by the 2.2 million-acre Kootenai National Forest.

Lincoln County Commissioner Brent Teske said that he hopes the county’s partnership with the Forest Service will have a “trickle down effect … with industry investing in wood fiber manufacturing, providing jobs to a community that is suffering economic hardship.”

This story was produced with support from the LOR Foundation. LOR works with people in rural places to improve quality of life.

This story was produced by The Daily Yonder and reviewed and distributed by Stacker.