How syringe exchanges in Tennessee reduce the spread of disease

This story originally appeared on Ophelia and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

How syringe exchanges in Tennessee reduce the spread of disease

In March 2024, Oregon quashed its efforts to decriminalize illicit drugs, which would have been the first of such laws in the nation, but the debate on how to curb the growing drug overdose epidemic in the United States rages on.

More than 100,000 Americans died from a drug overdose in the 12 months leading up to October 2023, according to the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. However, nearly two-thirds (64.7%) had a potential opportunity for intervention at least once, such as the presence of a bystander, a mental health condition, or a previous nonfatal overdose.

Syringe services programs are one of the provenly effective methods for decreasing overdose deaths as well as the spread of infectious diseases like HIV and Hepatitis C. SSPs are operated by community-based prevention programs that can offer other services such as testing, counseling, and medical treatment/wound care.

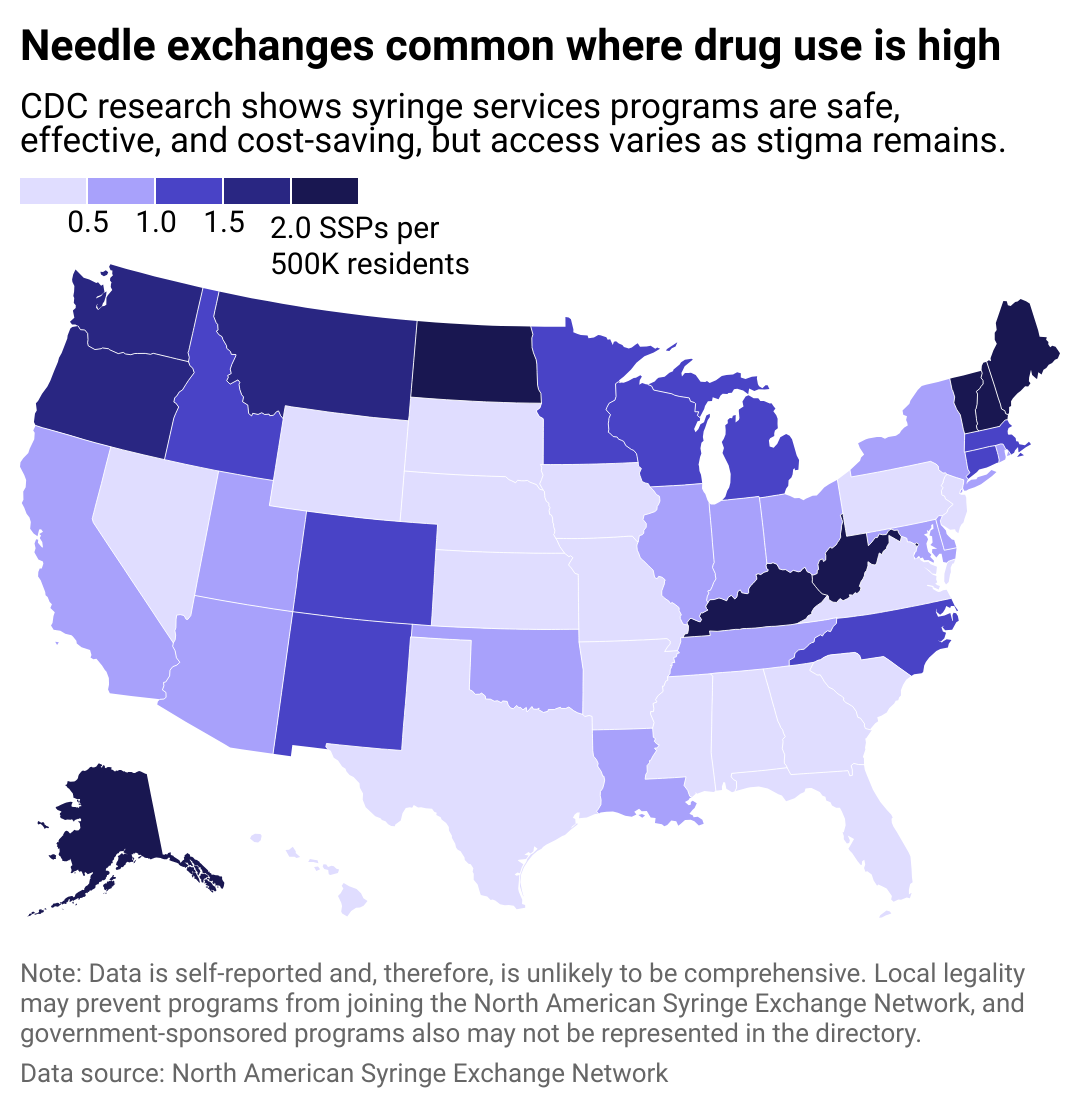

Ophelia examined data from the North American Syringe Exchange Network to determine which states have the most syringe services programs per capita. The number of programs in this analysis are self-reported to NASEN and are therefore unlikely to be comprehensive. For example, Kentucky had 32 SSPs in the database, but the state's Cabinet for Health and Family Services reported 84 operational sites as of June 2023. Five states (Kansas, Mississippi, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wyoming) had no exchanges listed.

Syringe exchange nonprofits typically receive federal funding, state funding, and grants. CDC research has found that syringe services programs reduce overdose deaths and crime, as well as the spread of discarded needles in public areas like parks. However, the stigma of substance use disorder and NIMBYism—the "not-in-my-backyard" mentality—have created obstacles to passing potentially lifesaving legislation.

Syringe exchange access varies by state

Despite the lifesaving potential of these kinds of programs, syringe exchanges were federally banned at the national level from 1988 to 2015. A study published in the International Journal on Drug Policy attributes the end of the ban to shifting perspectives and lessons learned during the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

The rise of HIV infection related to the growth of the opioid epidemic in the early 2010s was powerful enough to sway politicians who had been reluctant to embrace syringe exchanges. States in the years since passed their own laws to create exchange programs. Most recently, a bill authorizing community syringe exchanges passed in the Nebraska Legislature but was ultimately vetoed by Gov. Jim Pillen.

Syringe exchanges in Tennessee include:

A Betor Way SSP

Memphis, Tennessee

Bucket City Harm Redux

Murfreesboro, Tennessee

Live Free - Claiborne

Tazewell, Tennessee

Partnership to End AIDS Status, Inc

Memphis, Tennessee

Rubiela M Collins Exchange

Kingsport, Tennessee

Safe Point in Memphis

Memphis, Tennessee

Syringe Trade Education Program of TN Chattanooga

Chattanooga, Tennessee

Syringe Trade Education Program of TN Johnson City

Johnson City, Tennessee

Tennessee Harm Reduction

Jackson, Tennessee

Benefits and risks of needle exchange programs

Critics often argue that needle exchanges promote drug use at the expense of taxpayer dollars, or that they feel unsafe around the people with substance use disorder that use them.

Research conducted over three decades, however, shows that syringe exchange programs provide a benefit to communities, according to the National Institutes of Health.

A 2019 study from the National Bureau of Economic Research found that syringe exchange programs reduced HIV diagnoses by as much as 18%. They've also been shown to save taxpayers money. In Indiana, a state-implemented syringe exchange program is expected to save taxpayers $120 million. People who use syringe service programs are also five times more likely to begin a drug treatment program and three times as likely to quit injection drug abuse, according to the CDC.

This story features data reporting by Elena Cox, writing by Dom DiFurio, and is part of a series utilizing data automation across 46 states.