Lessons in civics are a privilege most often enjoyed by more affluent students in US schools

This story originally appeared on HeyTutor and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Lessons in civics are a privilege most often enjoyed by more affluent students in US schools

Americans' trust in government is at a record low. Fewer citizens participate in elections than other similarly developed democracies. To top it all off, young people have limited opportunities to learn about how U.S. governments, the justice system, and the courts work, according to recent survey data.

Civics activities have the potential to teach young adults their roles and responsibilities as active members of a democratically run society—yet school principals surveyed by Brookings report that few U.S. schools today offer extracurricular activities that could foster participation in civics.

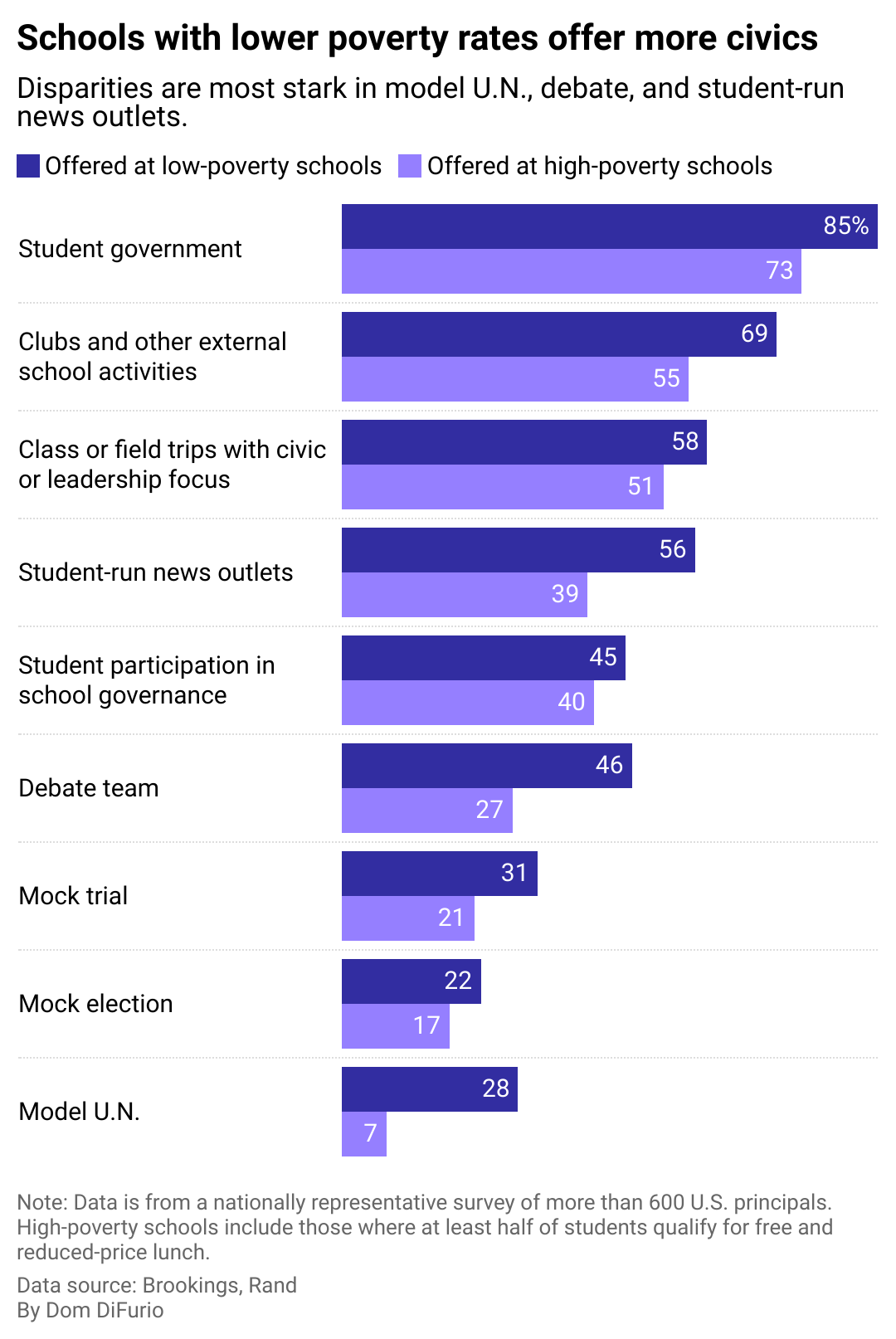

HeyTutor analyzed data from the nonpartisan, nonprofit Brookings Institution to illustrate how schools are incorporating civics into education, broken down by schools serving communities with high and low rates of poverty. Brookings partnered with Rand, a nonprofit think tank, to conduct a nationally representative survey of 650 U.S. high school principals.

American eighth graders' understanding of civics hasn't improved much since at least 1998, according to one measure tracked by the National Assessment of Educational Progress. The NAEP surveys students to measure their understanding of civics topics like government, the Constitution, and the rule of law.

Civics can be taught through participating in events like mock elections where students get to see firsthand how casting a vote translates into representation of their interests, or debates where they're exposed to the arguments driving popularly debated political topics relevant to their country. Though now outdated, the "I'm Just A Bill" Schoolhouse Rock! video explaining how a proposed bill becomes law is another example of creative civic education that succeeded in familiarizing a complex subject that would otherwise be inaccessible if not taught in a formal setting.

The NAEP survey also gauges students' feelings about the opportunity to learn about the functions of the U.S. government. Students who perform better on the civics understanding questions are more likely to say that their knowledge of civics helps them understand what's happening in the world and allows them to make a difference in their communities.

Advocating for more civic education in an article published in The Atlantic last year, Richard Haass, president of the Council on Foreign Relations, wrote that the U.S. is "not tied together by a single religion, race, or ethnicity. Instead, America is organized around a set of ideas that needs to be articulated again and again to survive."

Learning the ins and outs of government, the criminal justice system, the courts, and democratic elections has become all the more important as issues like misinformation, inequity, and the rise of global authoritarianism have grown in recent years, according to the nonprofit, nonpartisan social sciences research firm American Institutes for Research.

The organization advocates for the idea that civic knowledge is best learned through a combination of education and experiences. But not all students get an equal opportunity to partake in extracurricular activities like field trips, debate clubs, and mock trials, which have long fostered civic understanding and engagement in young people.

Who gets to learn about how their government works?

Aside from student government participation, civics-related opportunities for public school students are limited, according to survey data from Brookings.

While student-run news organizations are found in 56% of schools in communities with low poverty rates, the figure is closer to 1 in 3 for schools where more than half of the student body qualifies for free and reduced-price lunch.

Time dedicated to teaching about civics topics may not exist in many schools outside of social studies and history classes. Fewer than 1 in 3 students surveyed by the NAEP said their schools have dedicated teachers for civics education.

A 2019 study of state education laws regarding civics found that there may be room for stronger standards at the state level in much of the country. It found that 30 states require high schoolers to take a full semester of civics classes for graduation, only nine states require a full year or more, and 11 states have no requirements whatsoever for civic education in the curriculum.

Complicating the push for more civics is the necessarily controversial nature of the social topics relevant to civic experiences. Education and debate about politically charged civics topics such as racial equity have come under fire in recent years as parents have exerted more influence over school boards. Public trust in the honesty and ethics of grade school teachers has also taken a nosedive in recent years, driven heavily by Republican-identifying Americans whose trust seemingly evaporated in the aftermath of COVID-19-induced school closures. It comes as Americans' trust in most professions requiring expertise has fallen considerably.

These are factors civic education specialists have to reckon with as they work to expand teaching about the topic vital to young people's participation in U.S. democracy. In California, the Democracy Project has piloted a two-week course for social studies, history, and civics teachers around topics like immigration, human rights, and gun violence. Meanwhile, in Rhode Island, legislators are demonstrating that schools will need not only guidance but funding as they pursue more robust civics education. Legislators are now pushing for public funding after a survey found that 4 in 5 schools in the Ocean State lack a dedicated course despite a 2021 bill requiring students to be proficient in civics.

Story editing by Alizah Salario. Additional editing by Elisa Huang. Copy editing by Tim Bruns.