As more public schools offer prekindergarten, a teacher shortage is slowing progress

This story originally appeared on TeacherCertification.com and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

As more public schools offer prekindergarten, a teacher shortage is slowing progress

Universal pre-K has been shown to prepare children for school, narrow the achievement gap, and help reduce child care costs.

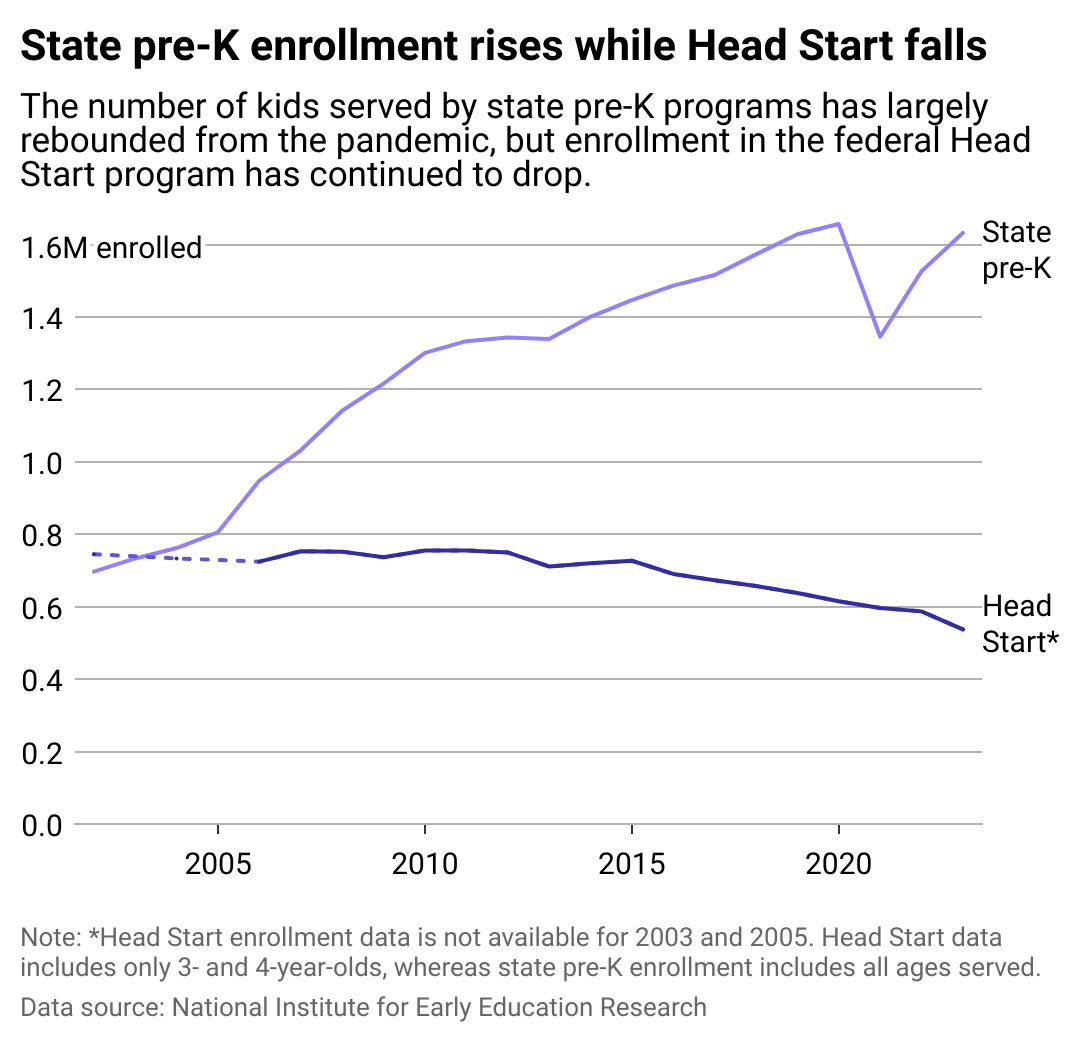

Still, just as state-funded pre-K programs have taken off nationwide, with enrollment increasing during the 2022-23 school year, a shortage of early childhood educators has thwarted progress toward providing a high-quality, equitable education for every 4-year-old.

The reasons for the shortage are complex. Low wages and burnout have led to high turnover across the board, but departures are particularly high among educators who work with infants and toddlers. Workplace stress in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as more stringent staffing requirements for teachers, make it increasingly difficult to fill vacancies.

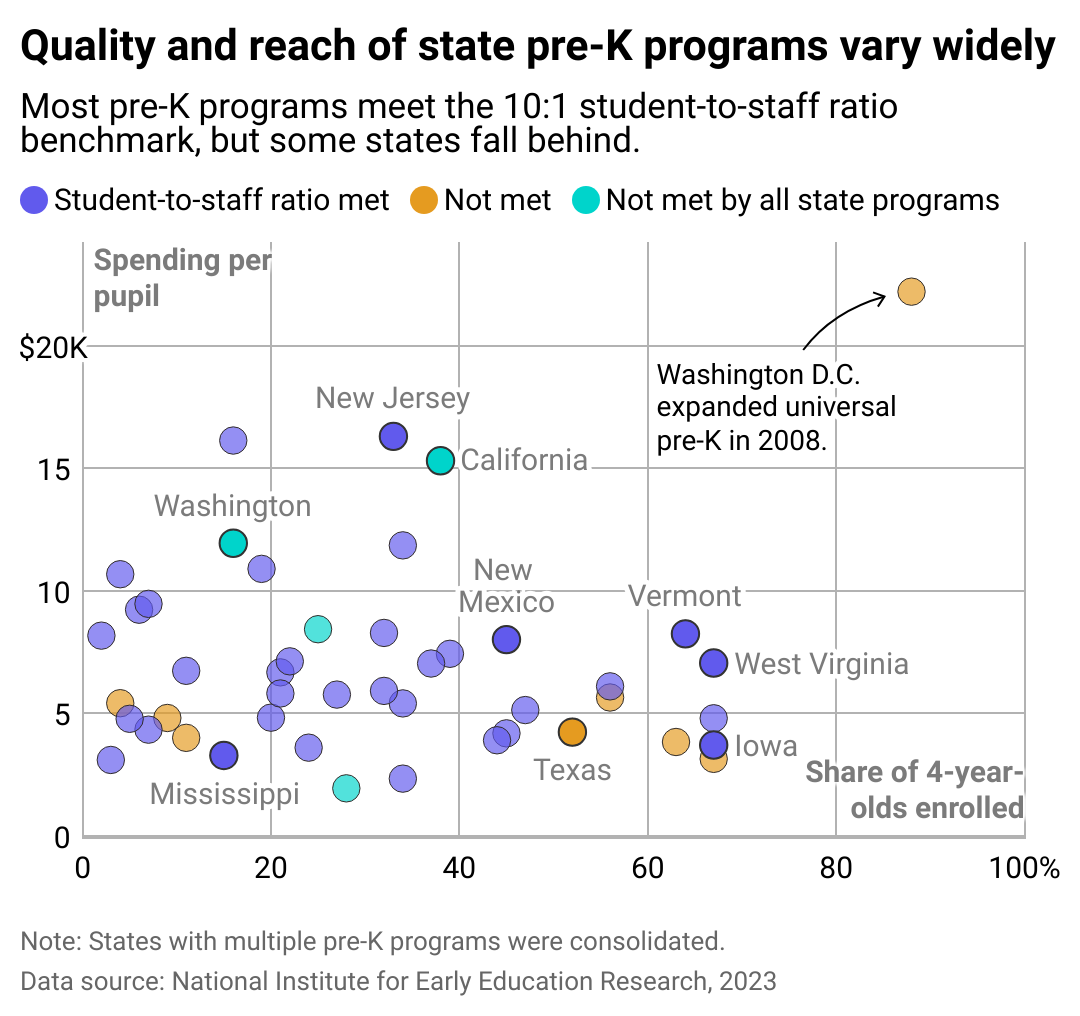

Finding qualified teachers is an issue in about half of states. Twenty-two states and Washington D.C. did not entirely meet credentialing benchmarks requiring teachers to hold a bachelor's degree. What's more, 31 states and Washington D.C. did not entirely meet benchmarks for assistant teachers, who must hold Child Development Associate credentials or the equivalent for the 2022-23 school year, according to a report from the National Institute for Early Education Research. Meeting student-staff ratios is also an issue nationwide.

To attract more candidates, some states are allowing a percentage of their early education lead teachers to receive waivers for policies that now mandate at least a bachelor's degree to be in the classroom.

During the 2022-23 school year, 44 states offered some form of public pre-K, with 35% of 4-year-olds attending state-funded preschool, according to the NIEER. However, because funding varies widely, the quality of these programs—and access to them—varies greatly across and within states.

TeacherCertification.com used data from the NIEER to investigate how states are pacing toward accessible, public pre-K programs.

Federally funded Head Start programs experience even greater teacher shortages

States fund early childhood education differently throughout the country, typically through general fund appropriations, block grants, and individual spending formulas. Massachusetts, for example, spends as little as $1,939 per child to fund pre-K programs, while upwards of $16,000 per child is spent in states like Oregon and New Jersey. Washington D.C., the nation's top spender on pre-K, allocates $22,207 per child.

In addition to universal state-funded programs, the federal government funds pre-K for children whose families meet federal low-income guidelines through the Head Start program. From birth to age 5, these children are eligible for the federal program, run by school districts, nonprofits, and for-profit child care centers. Faith-based institutions and tribal councils, formed by elected or appointed representatives from a Native American tribe, can also apply to receive federal Head Start funding.

In 2023, the Biden administration announced increased funding for Head Start programming, emphasizing boosting wages for the program's educators, who are currently among the lowest-paid workers in America. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, turnover for Head Start teachers and other staff members increased dramatically, from about 1 in 5 in 2019 to nearly 1 in 3 in 2022, according to an analysis of Head Start program data by the Urban Institute.

Teacher pay remains an obstacle to attracting and retaining qualified Head Start teachers. They earn an average of $35,000 annually, compared to $60,000 and $49,000, respectively, the average annual salaries for public school kindergarten and preschool teachers.

Moreover, the average Head Start staff vacancies quadrupled during the pandemic, from more than 2% in 2019 to nearly 9% in 2022. In both years, obtaining higher compensation elsewhere was the most common reason cited for departures, according to the analysis.

Universal pre-K varies widely and depends on accessibility, family income, and ZIP code

Despite offering universal pre-K, a term based on any state-funded preschool program where age is the only criterion for eligibility, accessibility continues to be an obstacle, depending on where you live. In practice, most states only serve a portion of eligible children. From only funding a limited number of hours per week to not providing transportation, many universal pre-K programs are simply inaccessible or impractical—often for the families who may need them the most.

Pre-K participation also varies widely across the nation. In Utah, merely 3% of children are enrolled in pre-K programs, while 67% are enrolled in states like Iowa, West Virginia, Oklahoma, and Florida.

Staff shortages also hinder states from offering enough slots for eligible children. Critics say that degree requirements for early childhood educators will decrease the size and diversity of the talent pool. At the same time, advocates suggest that additional credentials are the first step toward ensuring quality education.

Idaho, Indiana, Montana, New Hampshire, South Dakota, and Wyoming do not offer a pre-K program. Other states, like Georgia, fund pre-K programs through the state lottery, with funding levels fluctuating based on state and national lottery revenue.

Washington D.C. offers the closest to true universal pre-K, with 88% of eligible children enrolled in 2023. The district expanded pre-K significantly in 2008, making it the largest program in the country. While K-12 test scores have improved in the district since it began offering universal pre-K, helping it boast the highest maternal labor force participation rate in the nation, Washington D.C.'s commitment to spending on pre-K also has resulted in child care costs that are among the highest in the country.

"Since policies setting low minimal qualifications tend to go with low pay, it is hardly surprising that turnover among assistant teachers is quite high," the NIEER report stated.

Hopefully, as educators, policymakers, and parents gather more data about the impact of early childhood education, teachers will be compensated accordingly.

Story editing by Alizah Salario. Additional editing by Kelly Glass. Copy editing by Janina Lawrence. Photo selection by Ania Antecka.