20 products you might not know are from the Amazon rainforest

20 products you might not know are from the Amazon rainforest

Rainforests exist on every continent except Antarctica, but none is bigger, more diverse, more significant, and more threatened than the Amazon rainforest. Around 60% of the rainforest is located in Brazil, with most of the rest spread between Peru and Colombia, and much smaller sections distributed among six other South American countries. The largest tropical jungle on Earth, the Amazon accounts for more than half of all the remaining rainforest habitats left on the planet.

Scientists first coined the term "biodiversity" there—and for good reason. About 10% of all known plant and animal species live in the Amazon, but only one of those species can be blamed for the predicament currently facing the most biodiverse region on Earth. About 24 million people live in the Amazon, including hundreds of thousands of indigenous people. Beyond the extraordinary diversity of life, the Amazon sources the raw materials for all kinds of products that people use in their daily lives in the world beyond the jungle. Stacker used a variety of sources to compile a list of common products largely sourced from the Amazon rainforest—or from former rainforest land that was cleared for commercial use.

Until the 1960s, centuries after the European conquest of South America, most of the Amazon's interior was inaccessible and cut off to human activity. Over the past 40 years, however, nearly 20% of the Amazon has disappeared because of logging, agriculture, ranching, and mining. Wildly destructive fires have also devastated the Amazon, particularly in the last few years. In 2020, the Amazon Conservation Association and Monitoring the Andean Amazon Project estimates the Amazon lost 5 million acres of primary forest across nine countries.

Continue reading to find out how much you depend on products from the Amazon rainforest.

You may also like: How communities are dealing with invasive species across the U.S.

Soybeans

The fires currently devouring the Amazon started with a hasty rush to plant a massive cash crop in the form of a tiny bean that’s native to the Far East on the other side of the world. Soybean farming has long been a blight on the Amazon, with farmers destroying massive swaths of pristine jungle—often with fire—to make room for soybeans, which are used in everything from alternative milk and cooking oil to tofu and soy sauce. The vast majority of soybeans, however, don’t end up on dinner plates in vegan and vegetarian restaurants.

Beef

Agricultural deforestation causes most of the Amazon’s destruction, mainly from clear-cutting and burning for cattle ranching and soybean farming, two industries that are directly linked—about 80% of the world’s soybean crop goes into livestock feed. Brazil exports more beef than any country in the world and only three countries produce more beef than China. The tariff-driven trade war in 2019 compelled China to cut its U.S. soybean imports in half and instead place massive new soybean orders with Brazil, sparking a frenzied land grab by soy farmers who started hundreds of new fires every day to cash in on the boom.

Chocolate

Decades of cattle ranching have left the Amazon rainforest with a treeless dead zone the size of Spain, but some of those used up former grazing pastures are being reclaimed by the main ingredient in chocolate. Cocoa, which indigenous people were already stirring into drinks when the first Europeans arrived in the 1500s, is a far less-destructive crop because it enjoys shade and therefore doesn’t require clear-cutting. New re-foresting laws combined with a strong effort from conservationists have led to a massive cocoa-planting initiative that is poised to make the popular bean one of the Amazon’s most important exports.

Vanilla

Of the world’s 35,000 orchid species, vanilla comes from the only one that grows an edible fruit. The vining plant is native to Mexico, but Madagascar has been the vanilla capital of the world since a 12-year-old slave discovered how to hand-pollinate the flower on a Madagascar plantation in 1841. The vast majority of common “vanilla” products contain either no or almost no actual vanilla and instead use synthetic flavoring. The real stuff, however, comes not only from Madagascar—it grows and is cultivated in rainforest habitats like those in parts of Mexico, Costa Rica, and the Amazon.

Rubber

When Charles Goodyear accidentally discovered the process of vulcanization by combining sulfur with heated rubber in 1839, an obscure milky substance called latex became one of the most valuable products on Earth. The new demand was met with a brutal system of colonial forced labor that enslaved and killed millions of indigenous people and decimated huge swaths of rainforest, most notably in the African Congo and the Brazilian Amazon. Although synthetics largely replaced natural rubber in the post-colonial period, tapping rubber trees is now an important vocation for local people—many of whom are descended from rubber slaves—living in the Amazon.

Gold

Aerial photos of the Peruvian Amazon reveal tens of thousands of acres of dead, poisoned wastelands where lush rainforests once stood. The earliest European explorers entered the Amazon chasing rumors of gold, and today, thousands of illicit mines prop up Peru’s multibillion-dollar illegal gold-mining industry. Besides clear-cutting and deforestation, mining uses toxic chemicals like liquid mercury that contaminate local rivers and streams, making the effects of mining-based destruction especially hard to reverse.

Golf balls

With a little poking around on sites like eBay, it’s still possible to track down golf balls made with balata covers, but no known manufacturers still produce them today. From the turn of the 20th century until the 1990s, however, the best golfers in the world prized balata golf balls for their soft, but durable casings, which allowed golfers to put much greater spin on their shots. Those covers were produced from a rubber-like sap tapped from balata trees, which are native to the Amazon.

Food coloring

Achiote is a spice that’s common in many Mexican and Caribbean dishes, but in the United States, achiote is used mostly as a dye in food coloring. Made from the seeds of the evergreen Bixa orellana shrub, achiote-based food coloring is used to add a yellow hue to such foodstuffs as margarine, butter, smoked fish, chorizo, and cheese.

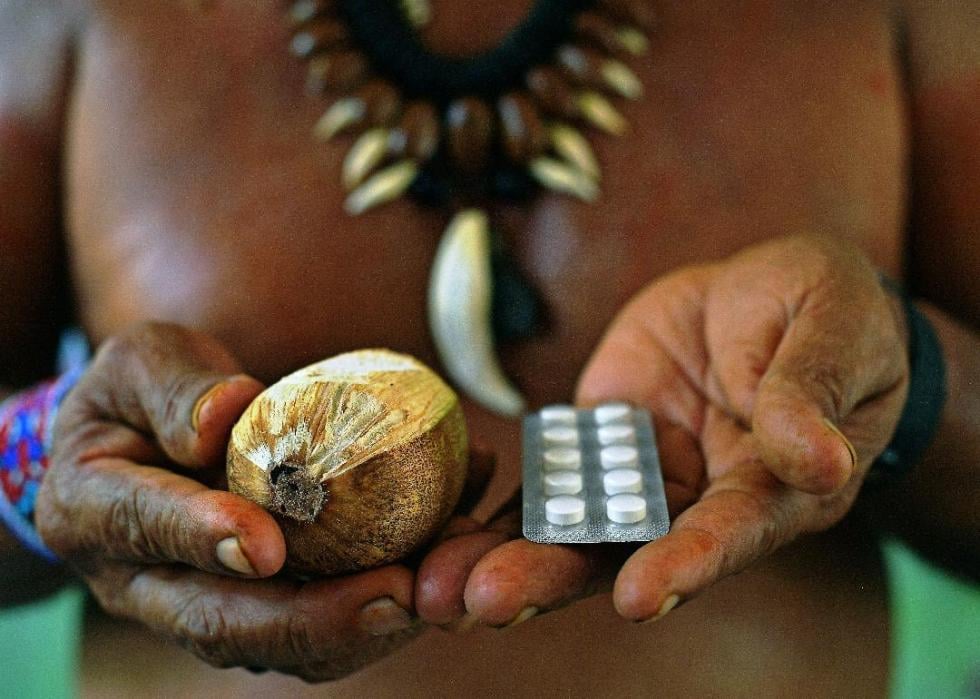

Medicine

Indigenous people knew for thousands of years that the Amazon was bursting with both deadly poisons and healing medicines, and the modern pharmaceutical industry has tapped into the rainforest’s medicinal offerings. Common treatments for Hodgkin’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and lymphocytic leukemia are derived from Amazon-based plants, as are active ingredients in anti-tumor medications and birth-control pills.

Diamonds

One of the most pristine sections of the Amazon is located in a remote section of Brazil that's home to a tribe that wasn't even discovered until 1969, but like the rubber slaves from colonial times, the tribe found itself in the unfortunate position of living on land that contained something valuable. In 2015, a massive untapped diamond reserve was discovered in the tribe's jungle reserve, and within just one year, the region experienced a deforestation rate 256% higher than the law allows. Today, the tribe's ancestral home is the #7 most deforested indigenous area out of 419 that exist in the Brazilian Amazon.

Black pepper

Black pepper is the most commonly used spice in the world, and Vietnam produces more of it than any other country. On the other side of the world in a different rainforest, however, the Piper nigrum L. climbing plant that produces peppercorns winds its way up the trees in the Brazilian Amazon, as well. Brazil produces about 40,000 tons of black pepper a year, 85% of which is exported.

Coffee

Like the cocoa beans used for chocolate, the plants that produce coffee beans have evolved to thrive in the shade of the jungle canopy, which makes them a natural fit for the Amazon. Although the large, bushing coffee plant originated in Ethiopia and Sudan, Latin America grows half of the world’s coffee today. Much of that comes from the Amazon, and as one of the most significant global commodities, coffee is a $30-billion-a-year industry.

Wood

Trees from the Brazilian rainforest produce some of the finest, most durable, most rot-resistant wood in the world, and exotic hardwoods like tigerwood, purpleheart, ipe, and, most commonly, Brazilian mahogany, have been prized by builders for generations. With some variations fetching thousands of dollars for a single tree, the Amazon represents an endless expanse of dollar signs for people who earn a living by turning trees into lumber—but the expanse is not endless. Logging, both legal and illegal, has been one of the primary drivers of deforestation for decades, but it takes at least as many decades for a single one of those trees to grow to maturity.

Brazil nuts

Brazil nuts are more valuable than nearly any other nontimber product to come out of the Amazon. Brazil nut trees are among the tallest in the entire rainforest, towering over 160 feet to the ceiling of the canopy and their dense, hard, nut-containing fruits weigh five pounds and crash to the forest floor like missiles. Despite their massive size, however, Brazil nut trees are highly dependent on ecological stability, as they can’t survive without animals like bees and agoutis, as well as other plants.

Corn

The global outcry over deforestation pressured many farmers to leave the Amazon rainforest and plant their crops farther south in the region of Brazil known as the Cerrado biome. The largest tropical savanna in South America, the Cerrado is a vital ecological zone that's home to 5% of the world's species, and just like its Amazonian neighbor to the north, industrial agriculture is wiping it out. Corn has been vital to people of the Amazon for thousands of years, but when large-scale modern farms moved their operations to the Cerrado, one ecological disaster was traded for another.

Sugar

The Brazilian government is considering lifting a nearly decade-old ban on opening the Amazon to the production of sugarcane for the biofuel industry. Brazil’s sugarcane biofuel industry formed an unlikely alliance with 60 nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) urging the government not to lift the ban, a move they say would hasten destruction of the rainforest to the brink of no return. Large-scale sugar operations are already leading to rapid deforestation in the Bolivian Amazon and destroying massive sections of the Cerrado savanna.

Palm oil

From food and cosmetics to fuel and cleaning products, palm oil is found in hundreds of commonly used products, and President Jair Bolsonaro is intent on making Brazil a global leader in palm oil production. That, however, would come at the expense of the Amazon rainforest. The amount of Amazon land turned over to palm oil producers in Brazil doubled between 2004 and 2010, and it’s predicted to double again by 2025.

Rice

Brazil is the #9 largest rice-producing country in the world and the largest anywhere outside of Asia. Like corn, rice has been a critical crop to Amazonian people for thousands of years, but modern agricultural practices have destroyed countless acres of rainforest to make room for massive industrial rice-growing operations.

Bananas

Bananas are the fourth-largest fruit crop in the world and the single most popular fruit in the United States—and many of them are grown in the Amazon. First introduced to South America by the Portuguese in the 16th century, bananas grow in every high-humidity tropical region on the planet.

Pineapples

Pineapples were a highly prized commodity among the European social elite in the 1700s and 1800s after Spanish conquistadors brought them back from Europe. Their roots in the Amazon, however, date back much earlier. South American Tupi-Guarani Indians grew and ate pineapples for thousands of years before European contact.

You may also like: Superfoods that have been used by other cultures for generations