How climate change is affecting America's national parks

How climate change is affecting America's national parks

Yellowstone National Park regularly receives over 4 million visitors during its peak season. Its geothermal features, wildlife, and scenery make it one of the most popular parks in the U.S. But last June, park officials closed the more than 2 million acre park for over a week due to historic levels of flooding.

Reports later showed precipitation elevated water levels to record heights. It's difficult to attribute individual events like the historic flooding of Yellowstone directly to climate change. However, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports show North America's rain storms and subsequent flooding have increased overall due to greenhouse gas emissions.

America's national parks are home to some of the most breathtaking environmental extremes. From the rich biodiversity of the Great Smokies to Zion's red cliff sides, the parks' popularity is rooted in their unique geologies and ecologies, much of which formed throughout millions of years. But as human-driven emissions accelerate climate change, national parks will face drastic changes by the century's end.

Stacker referenced research from climate scientists, the National Parks Service, and the U.S. Geological Survey to examine how climate change impacts America's national parks.

Scientists warn that extreme weather events will only become more common as climate change increases the temperature in the atmosphere. Extreme weather events are some of the most recognizable changes people see in national parks. Still, over the next century, slower changes like increasing temperatures and changing precipitation will also take a toll on public lands.

Rising temperatures

National parks in and near the Arctic were largely projected to have the greatest increase in temperature over the next century. Declining snow and ice cover will accelerate temperature change in the region.

The average temperature increase across all sites managed by the National Parks Service, including monuments, historical parks, recreation areas, and other designations, was 4.9 degrees Celcius under high emissions scenarios. Reduced emissions showed an average increase of 1.7 degrees C, compared to previous century averages of 0.5 degrees C. These projections largely remain the same when looking exclusively at the 64 national parks, but the historical temperature increase is closer to 0.6 degrees C.

Patrick Gonzalez, executive director of the Institute for Parks, People, and Biodiversity and former principal climate scientist for the National Parks Service, published projections under different emissions scenarios for every park in the U.S.

Gonzalez and his team found temperatures in national parks are rising twice as fast as the rest of the country. Between 1895 and 2010, annual precipitation declined 12% across parklands compared to 3% in the U.S. as a whole.

Warmer temperatures combined with extended periods of drought can impact the plant and animal life that have become synonymous with particular parks. Saguaro National Park's eponymous cacti have failed to establish themselves in the park since the 1990s. In California's Sequoia National Park, the mortality of ponderosa and sugar pines during one particular drought period was seven times the normal mortality rate for nondrought periods as measured from 2004-2007.

Parks can practice resilience in the face of climate change threats. Heat-resistant coral in Biscayne National Park can preserve the reef ecosystem. In Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, establishing populations of rare and endangered plants outside of their usual range can protect them ahead of drier and warmer conditions.

Mitigation alone won't save America's parks, however. "The fundamental solution to protecting our national parks is to cut the carbon pollution from cars, power plants, deforestation, and other human activities that cause climate change," Gonzalez told Stacker.

Lowering emissions to the threshold established by the Paris Agreement could curb expected warming in national parks by up to two-thirds compared to warming in the highest emission scenarios by 2100, according to Gonzalez's research.

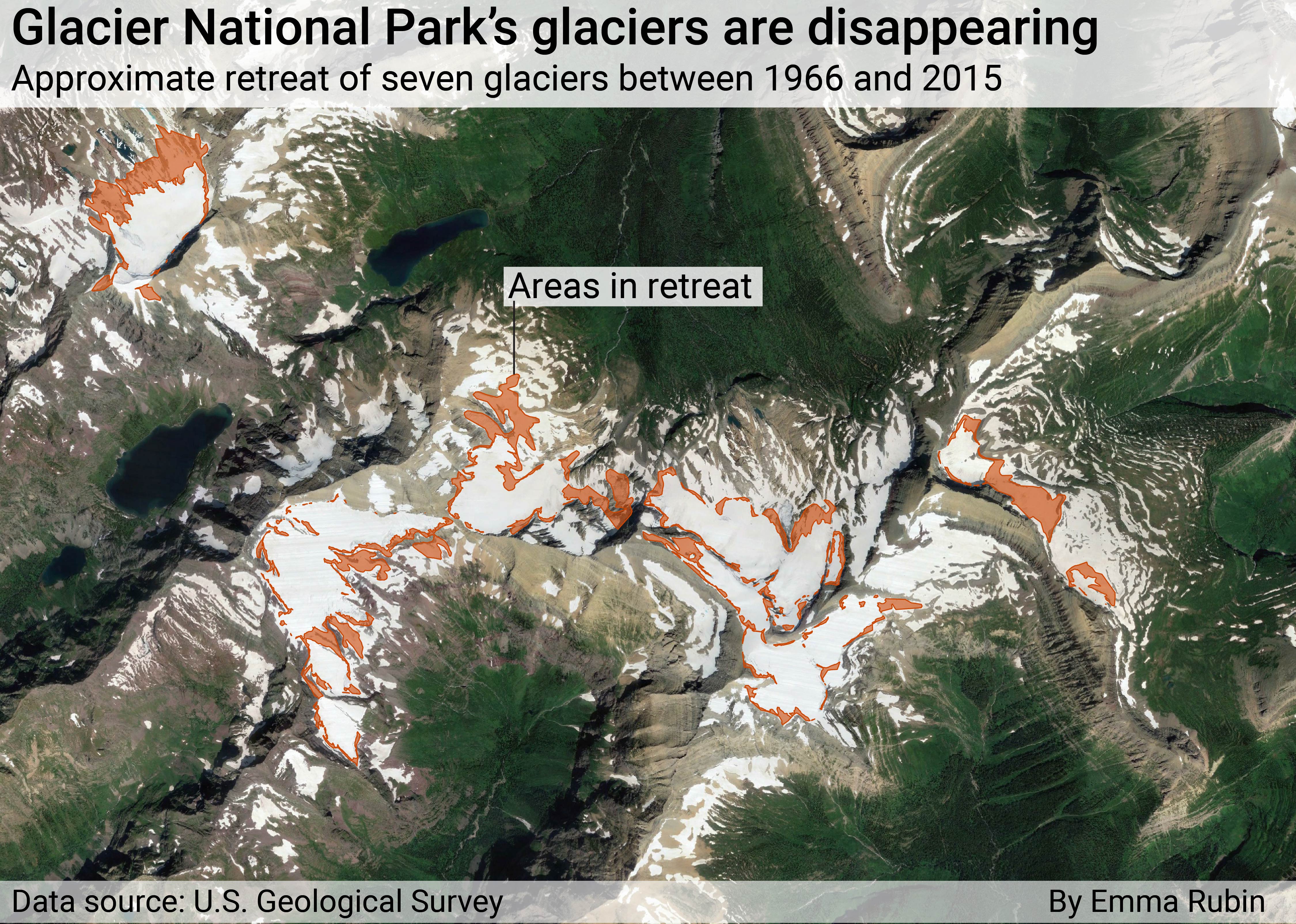

Glacial retreat

Between 1966 and 2015, Glacier National Park lost nine named glaciers. The National Parks Service additionally estimates that today some of the 26 glaciers in its last count may also be too small to meet the 0.1 square kilometer minimum.

The glacial retreat in the park has been ongoing since the end of the Little Ice Age in 1850. While natural climate change has played some role over the past century, human-caused climate change has accelerated recent losses. It's unclear when the parks' glaciers could disappear entirely, but it may already be too late to save the Montana parks' namesake. Even under reduced emissions scenarios, the glaciers are expected to disappear by the end of the century.

The losses are more than aesthetic. Glaciers provide fresh water and support stream ecosystems during the summer, providing cool water vital for the survival of species such as bull trout. Declining glacial volume means runoff may not be able to offset increasing water temperatures from hotter summers.

Other parks' glaciers are also suffering. Between 1984 and 2021, at least 14 of Kenai Fjords National Park's 35 named glaciers lost substantial area. Melt in environments like Alaska also contributes to sea level rise.

Sea level rise

Along the South Florida coast, the mingling of freshwater and saltwater tides creates unique ecosystems that support orchids, mangroves, and buttonwood trees. There, Everglades National Park, established in 1934, covers nearly 5 million acres and is the largest tropical forest in the U.S. Rising sea levels are, unfortunately, making waters in the area saltier, shifting the boundaries of its ecosystems.

Cape Sable, a freshwater marshland, was transformed in the early 20th century by attempts to dry the area for agricultural purposes. This process resulted in much of the freshwater being pumped out to sea. As a result, sea level rise combined with storm surges filled the area and surrounding lakes with salty water and marine sediment, disrupting the habitat.

Recent damming of the canals originally built to drain the area has helped stop freshwater flow out of Cape Sable. This effort proved particularly valuable in the aftermath of Hurricane Irma. Scientists found the restored habitat withstood the storm's effects much more robustly than the area's unprotected portions, demonstrating that restoring wetlands in coastal environments improves resilience in the face of rising sea levels.

Outside the Everglades, a quarter of all sites managed by the National Parks Service are along the coast. A May 2018 NPS study found that by 2100, sites along South Carolina's outer banks will see the highest sea level rise. Other sites throughout the Southeast will experience heightened risks from storm surges during hurricanes and tropical storms.

Animal life

Over 600 endangered and threatened animals live in park sites, according to the National Parks Conservation Association. Urban development, pollution, and other human activity have driven these animals to at-risk statuses, but public lands provide safe habitats with limited human encroachment.

Every year, thousands of sea turtle hatchlings emerge along the Southeast coast. The reptiles, about 2 inches when they hatch, face natural obstacles during their nocturnal shuffle to the ocean as well as the threat of predators like crabs. Human threats such as litter, fishing refuse, and beach activity further complicate the journey.

Four of five sea turtle species in the U.S. are endangered due to human threats. National parks like Dry Tortugas, the most active nesting site in the Florida Keys, offer a refuge for sea turtles and other animals.

As climate change shifts environments, however, protected lands that were once ideal habitats could become inhospitable. Low-lying islands in Dry Tortugas National Park will likely be submerged due to sea level rise by 2100, reducing the area favored by turtles amid other intensifying threats due to climate change.

Wildfires

Decades of fire suppression efforts during the mid-20th century led to debris buildup, which is now amplifying climate-fueled wildfire seasons in the West. Between 1984 and 2015, the area burned by wildfires in the Western U.S. doubled. Research has attributed a large share of this growth to climate change.

Three fires in 2020 and 2021 were estimated to have killed 13-19% of the Sierra Nevada's sequoia population. Sequoias are notably resistant to fires, and low-severity events are even critical to their growth. Still, large-scale events are damaging their range within and outside national park boundaries.

Prescribed burns can prevent large-scale fires that become hard to control, but climate scientists say prolonged drought and increased heat will continue to make fire impacts more severe. In high emissions scenarios, wildfires could even start impacting parks that haven't historically been affected, such as the Gate of the Arctic National Park and Preserve and Noatak National Preserve in Alaska.