Participation is down 40% in this agricultural program that protects wildlife, water, and soil

This story originally appeared on Thistle and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Participation is down 40% in this agricultural program that protects wildlife, water, and soil

Paying farmers to fallow their fields for conservation only works if the price is right, no matter how noble the cause. In some regions of the United States, farmers can net higher returns by continuing to harvest crops like corn and soybeans than they would if they leased their land for conservation efforts.

In 2021, the Biden administration set a "30 by 30 goal" by which the U.S. would conserve 30% of all land and waterways by 2030. Achieving this goal requires leveraging existing programs like the Conservation Reserve Program.

Under the CRP, established in the 1985 Farm Bill, the government pays farmers to take portions of their eligible farmland—typically marginal, less productive acres—and temporarily grow grasses, trees, and native plants instead of crops. The voluntary program is primarily utilized for climate change mitigation purposes such as carbon dioxide sequestration, land erosion reduction, water quality improvement, and wildlife habitat creation. There are 22 million acres of farmland currently enrolled in the program, representing a $1.77 billion government investment—or about $80 per acre on average.

While beneficial in the short term, this system is far from perfect. When the 10-year land lease period expires, farmers can choose to go back to using their land for agriculture, potentially undoing conservation gains.

The Environmental Working Group estimates that if all the land enrolled in the CRP over the last three years were plowed, it would release more than 2 million tons of soil carbon back into the atmosphere—just one example of the drawbacks of these temporary incentives. Similarly, the USDA estimates the total acreage currently devoted to the program is keeping 12 million tons of carbon dioxide from entering the atmosphere.

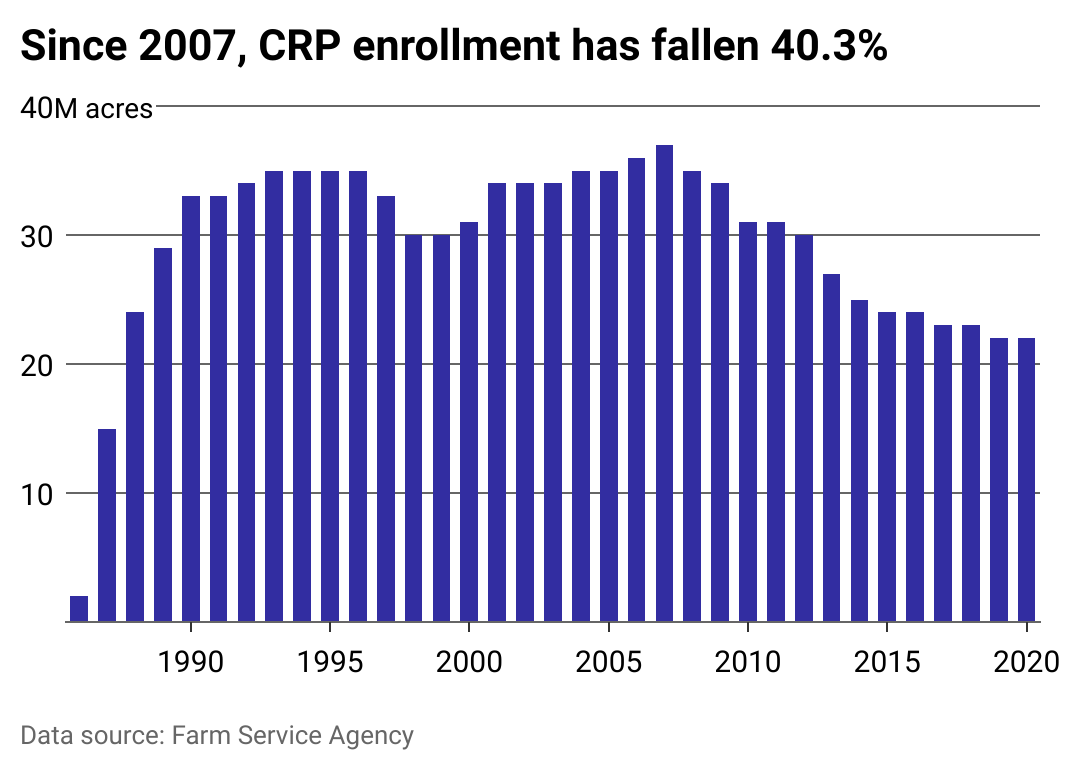

Thistle compiled data from the Farm Service Agency to look at how enrollment in the Conservation Reserve Program has changed over time. Contract expirations and variable soil rental rates across the country have, in part, contributed to declining enrollment over the last 15 years. Soil rental rates vary by region and agricultural use and are tied to local land rental market prices. While some parts of the U.S. are experiencing an increase, others have experienced a decrease in pastureland and cropland values in recent years.

There is less land in the Conservation Reserve Program than there used to be

Some of the CRP enrollment declines can be attributed to expiring contracts. The drops may also be related to the complex economics of enrollment—or the comparatively uncomplicated fact that some enrollees are simply getting lower soil rental rates for their acres based on the market value in their region.

When facing a 4-million-acre enrollment shortage in 2021, the USDA calculated the environmental impact this would have. The agency estimated, among other effects, the loss of 4 million game and grassland birds, the addition of 90 million pounds of nitrogen entering waterways, 30 million tons of soil erosion leading to water pollution, and 3 million metric tons of carbon dioxide unsequestered by vegetation.

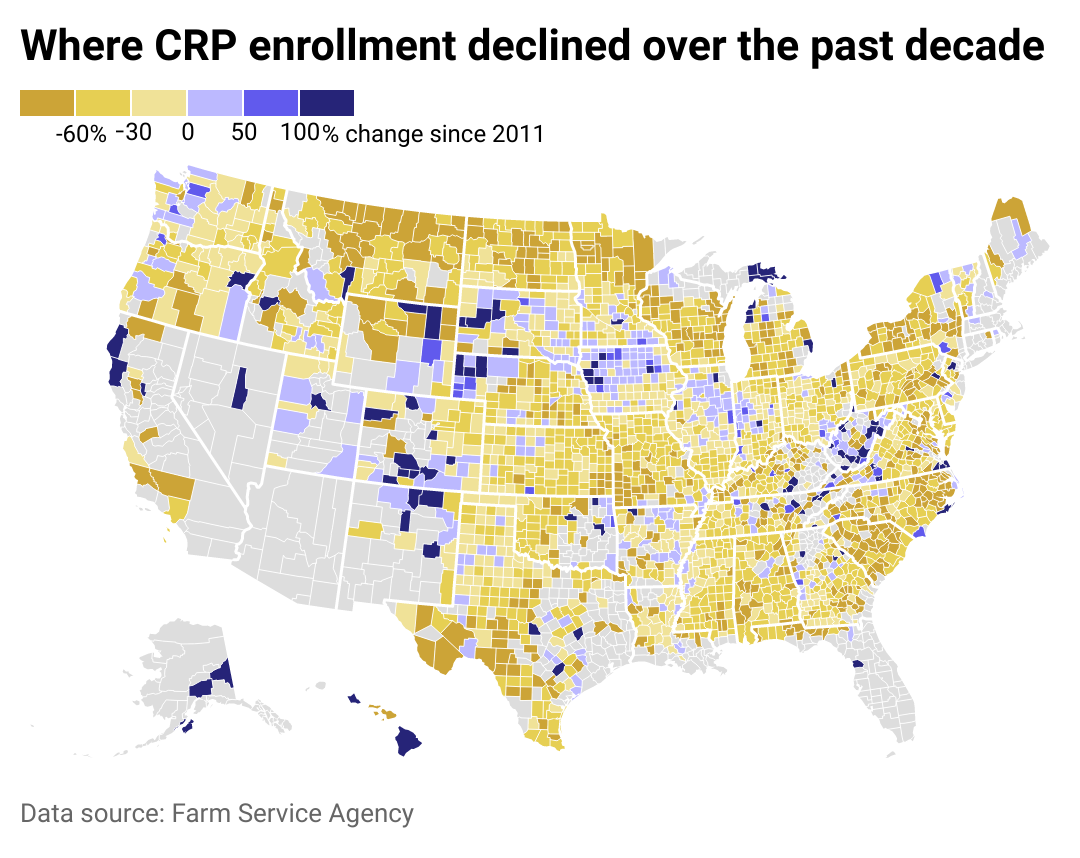

Most counties have seen declines in participation over the past 10 years

Counties that have seen growing enrollment have likely benefitted from expanded CRP eligibility and offerings such as establishing grassland minimum rental rates—a change helping more than 1,300 counties across the country.

Enrollment has been most heavily concentrated in the Upper Midwest and Great Plains regions of the U.S., with enrollment in the East being the lowest. The CRP caps enrollment at 25% of a county's total cropland.

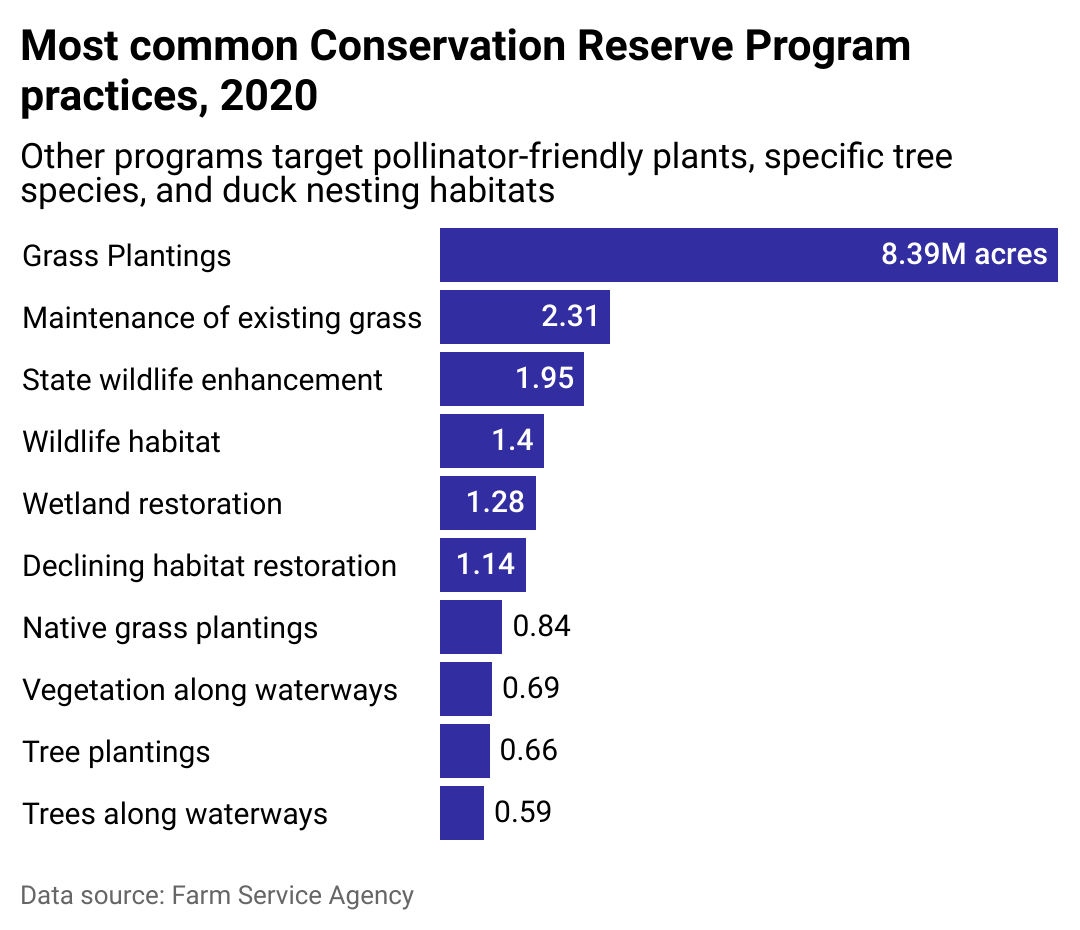

Grassland establishment and habitat expansion are among the most common programs

Planting and maintaining grass are the most common CRP practices because of grass' wide array of benefits and low cost relative to other conservation practices. Grass can prevent soil loss from wind and water erosion, create habitats for bird species, improve water quality by filtering sediments and retaining nutrients, and store carbon.

Riparian buffers, referred to here as vegetation along waterways, are less commonly implemented due to their scale but are essential for their role in preventing bank erosion and protecting waterways from agricultural runoff.

New changes from the USDA seek to improve participation

To increase enrollment, the USDA made several significant program changes over the past two years, including rate flexibility, more contract options, increased incentives, increased payments for certain practices like those that improve water quality, and greater technical assistance.

Additionally, the USDA enrolled the first three tribal nations in the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program, an offshoot of the CRP, in 2021. Together, the Cheyenne River Sioux, Oglala Sioux, and Rosebud Sioux tribes will allot up to 3 million acres of tribal land for conservation.