This story originally appeared on Northwell Health and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Breaking down racial disparities in diabetes prevalence

Diabetes is a disease about which there are countless myths, misconceptions, and even moral judgments. Widespread cultural beliefs about who develops diabetes—as well as how and why—contribute to stigma and shame around the illness while obscuring its real, and very troubling, social determinants.

To many, diabetes—particularly Type 2—is associated with bad decision-making: It is seen as a consequence of unhealthy dietary and lifestyle choices, and therefore somehow different from other chronic illnesses like cancer or Crohn's. Others may consider diabetes a product of body fat or even a disease specific to the biology of certain racial or ethnic groups.

Diabetes stigma is pervasive. Two studies published in 2020 in association with the University of Connecticut's Rudd Center for Food Policy & Health found this to be the case not only socially but within medical settings as well. In one study, 53% of surveyed adults with Type 2 diabetes believed they could have prevented developing the condition, and nearly 1 in 2 experienced judgment for their dietary choices and felt the need to hide their condition from others.

A second study showed that 44% of diabetic adults felt judged by their health care provider for their weight and condition. In an earlier 2017 study of people with either Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes, 81% of those who reported stigmatization indicated they felt perceived as having a character flaw, or that having diabetes was a "failure of personal responsibility."

Yet medical researchers have debunked factors like individual choice, body fat, or ethnic biology as the driving forces behind diabetes. Instead, the disease is one of many health conditions that expose existing racial and class-related health disparities. The impacts of social inequities, including conditions created by systemic racism and poverty—like access to quality, affordable health care, nutritious foods, and a clean environment—as well as other factors like family history, have been shown to heavily influence diabetes rates.

These inequities continue to also impact the treatment of those who have already been diagnosed with diabetes. The price of insulin in the U.S. has exploded by more than 600% over the past two decades, far surpassing inflation rates. Reports have accused pharmaceutical companies of taking advantage of the fact that insulin is a lifesaving drug for millions of people, knowing that it will likely be bought at any price.

The increasingly high cost of insulin disproportionately impacts low-income and uninsured populations, putting them at higher risk of dangerous complications and death. The Inflation Reduction Act capped copays on insulin for Medicare subscribers at $35, but set no limit for Medicaid, employer-provided, or individually purchased insurance coverage.

Using data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and World Bank, Northwell Health looked at racial disparities in the prevalence of and morbidity from diabetes in the U.S. Both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes were included in the data, but since Type 2 is far more common, most of the trends represented in the analysis reflect the rates of Type 2 diabetes.

Diabetes rates in the US

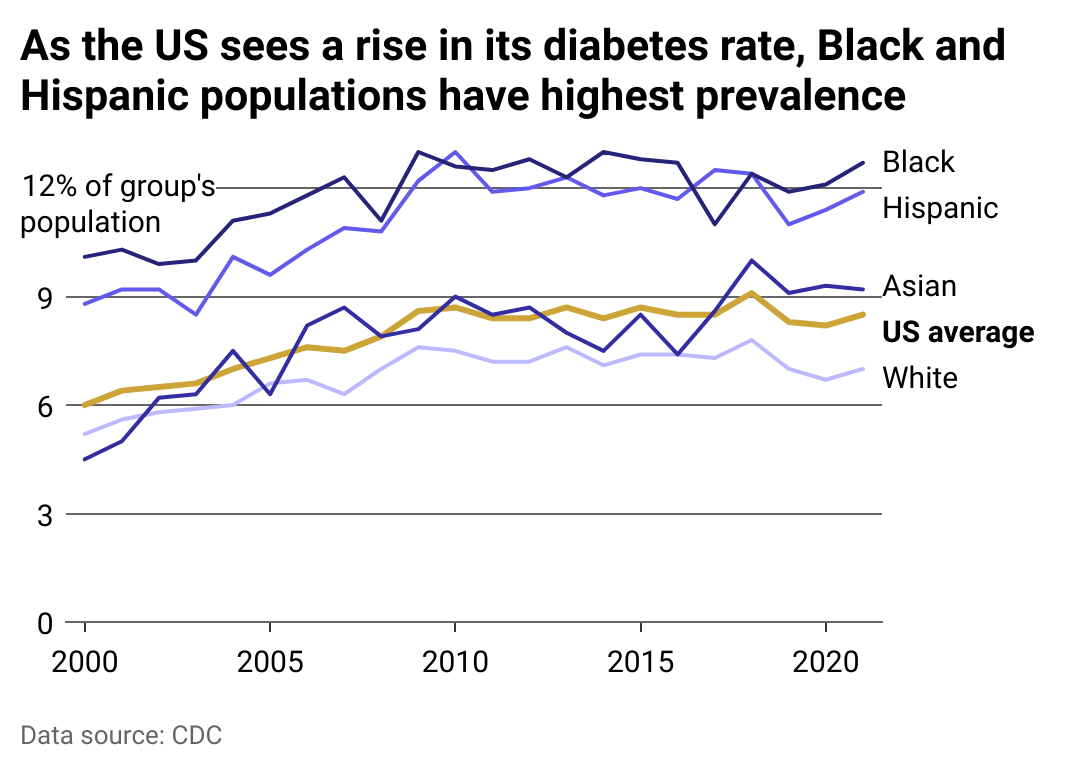

The U.S. has one of the highest rates of diabetes in the world, but the disease does not fall across the population evenly. According to the CDC, Black and Hispanic populations experience much higher rates of diabetes than white populations; Asian populations have diabetes rates just above the U.S. average.

Native Americans also experience disproportionately high rates of diabetes, according to data from the Indian Health Service. As much as 14.5% of American Indian and Alaska Native populations suffered from diabetes in the 2018-19 year—the highest rates of diabetes of any racial or ethnic group.

Studies of racial disparities in diabetes rates have shown that a range of economic, social, and geographical factors linked to systemic racism impact diabetes prevalence. According to the American Journal of Public Health, poverty, high exposure to toxins, limited access to affordable nutritious foods, and inaccessible health care services are just a few of the risk factors that have been shown to elevate the risk of diabetes—risk factors that Black and other non-white Americans experience at disproportionate rates.

Despite the higher rates of the disease among non-white populations, these populations are not always accounted for in clinical trials for treatment. A 2017 analysis of diabetes treatment testing revealed that, out of 19 individually tested drugs, only four were tested in Black, Latino, and Asian populations (the others were selectively tested among those populations, but not in each of them), even though these groups make up a large percentage of those who suffer from diabetes in the U.S. Native Americans' participation in clinical trials for diabetes treatment was not included in the analysis.

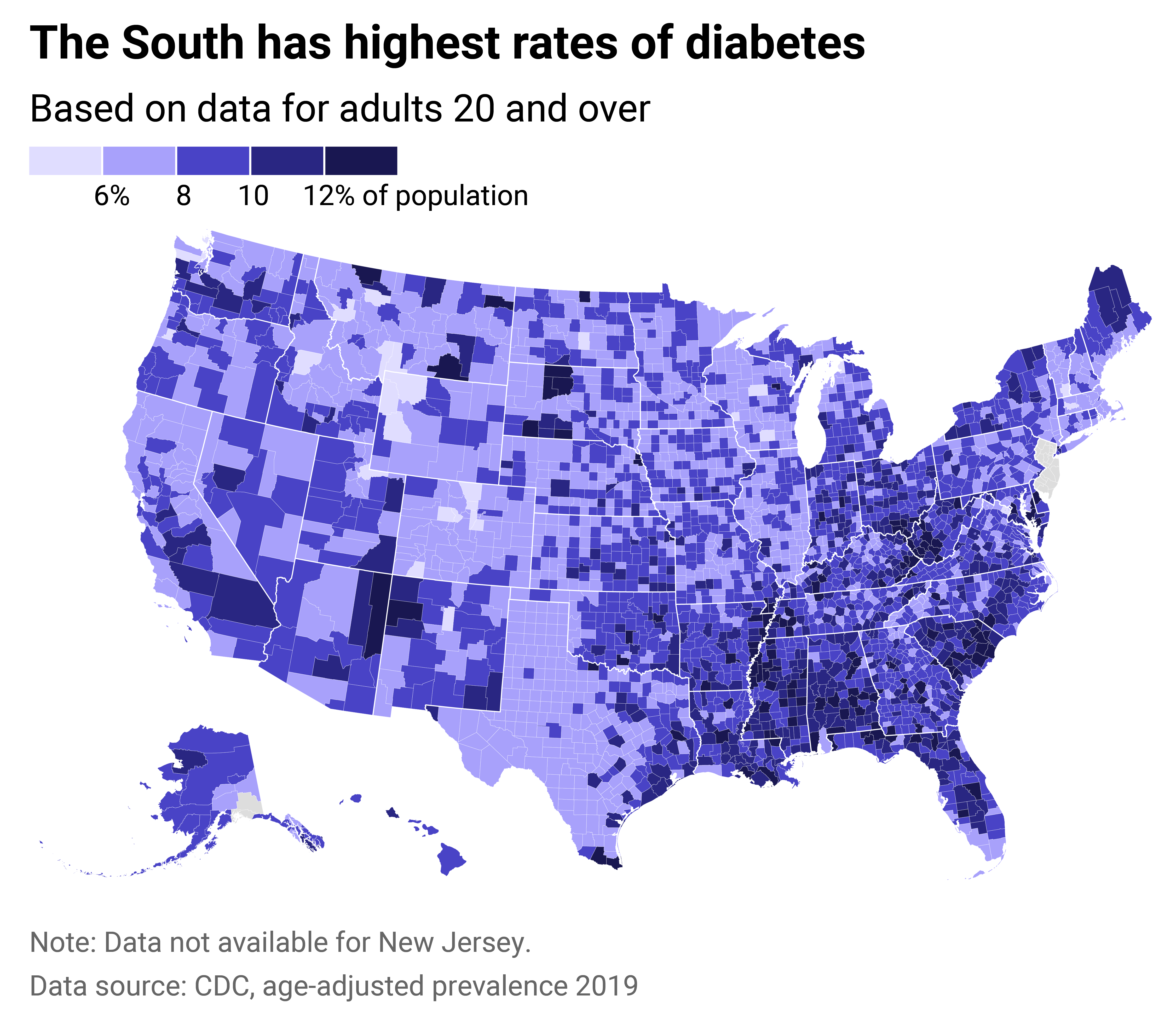

Regional disparities

Diabetes rates are particularly high in the Southeast and Appalachian regions of the U.S., a cluster that the CDC dubbed the "diabetes belt" in 2015. Determined using county-level data, regions were included in the diabetes belt if at least 11% of residents were diagnosed with the disease. Overlapping heavily with the so-called "stroke belt," the disparity in diabetes rates in this region mirrors specific population concentrations—a majority of Black Americans live in the Carolinas, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, according to Census data.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, many of the factors associated with greater diabetes prevalence are particularly concentrated in this region. Many of the counties with high diabetes rates are rural, where accessing health care is more difficult due to far distances between residents and providers, limited public transportation, and lack of affordability. In addition, many states in the region have not adopted expanded Medicaid access, which would cover more low-income individuals and offer an enhanced federal matching rate, making affordable health care even less accessible.

Disparities among Pacific Islanders

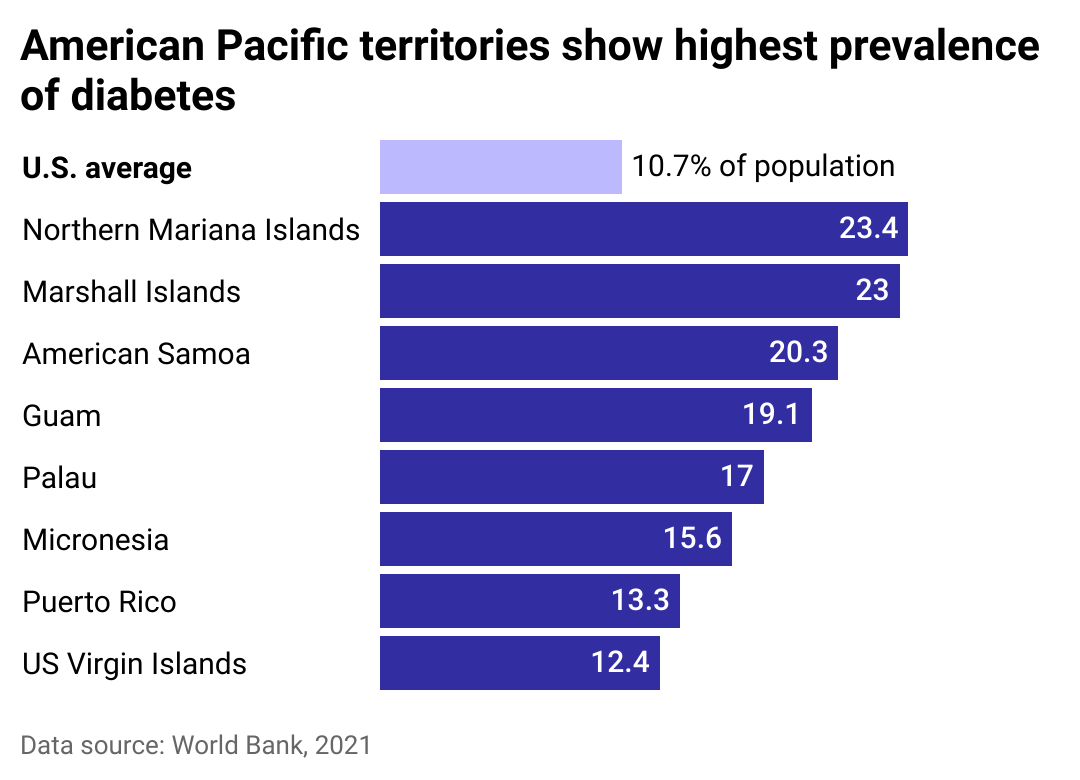

Over the past several decades, Pacific island nations have experienced some of the highest rates of diabetes in the world, and much higher rates than the continental U.S. But it has not always been this way: Studies have shown that colonization of the islands had a seismic impact on health outcomes, as well as economic and social well-being.

Before Japanese, Spanish, American, and German forces occupied the Pacific islands, Indigenous Pacific Islanders mostly ate native staple foods like taro, breadfruit, yam, and cassava. The arrival of colonizing powers meant the replacement of many of these foods with heavily processed foods and different types of starches, which caused a fundamental shift in general nutrition.

Adding to the influx of less nutritional foods into Pacific island nations was the intentional sale of nonnutritious (but affordable) food waste, like turkey tails, by the U.S. to the islands, enabling American industries to profit while causing enough health issues that American Samoa banned turkey tail imports in 2007. These profound changes to diet are thought to have helped catalyze a rapid increase in diabetes in a population that previously had very low rates of the disease.

Disparities in mortality

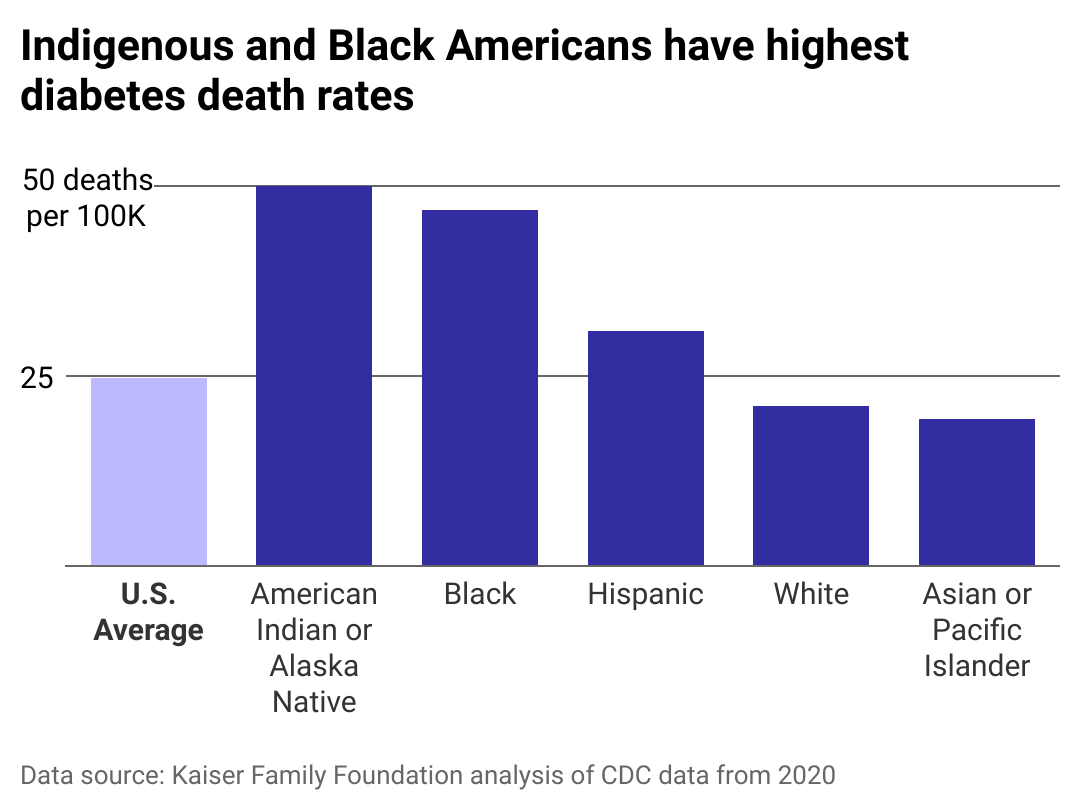

In 2021, diabetes was the eighth leading cause of death in the U.S. Indigenous Americans, Alaska Natives, and Black Americans have disproportionately high diabetes death rates compared to the national average. Diabetes is not usually a deadly illness, so long as it is treated and monitored carefully. It can, however, develop into a fatal disease if it goes untreated, and can also result in complications like heart disease and a higher risk of stroke.

Studies have shown that diabetes mortality is influenced by the same risk factors that put Black and Indigenous Americans at higher risk for diabetes in the first place: segregation, poverty conditions created by systemic racism, and lack of access to affordable health care. For those without equitable access to affordable treatments and monitoring by doctors for potential complications, diabetes is more likely to become deadly.