Catching cancer early lowers risk of mortality, but screening is the first step

This story originally appeared on Northwell Health and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Catching cancer early lowers risk of mortality, but screening is the first step

The American Cancer Society expects to hit a bleak milestone this year: New cancer cases in the U.S. are predicted to cross the 2 million mark for the first time.

Simultaneously, the risk of dying from cancer has steadily declined over the past three decades due to treatment advancements, fewer people smoking, and, importantly, detecting cancer early.

"Screening is really crucial in cancer care," Dr. Shanthi Sivendran, American Cancer Society's senior vice president of cancer support, told Stacker. "The earlier we can catch a cancer, the better the outcome and potentially the less intensive the treatment has to be."

Northwell Health partnered with Stacker to explore cancer screening data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, breaking down screening statistics by geography and race.

There aren't ways to detect many types of cancer early, but for four of the cancers increasing in numbers across the U.S.—breast, prostate, colorectal, and cervical—screening tests are available. The tests for cervical and colorectal (which includes colon and rectum cancer) can prevent cancer in some cases since precancerous lesions may be detected and removed.

Experts at the ACS recommend people get cervical cancer screening starting at age 25; breast or prostate cancer, as well as colorectal cancer screening, starting at age 45; and discuss getting lung and prostate cancer screening with a doctor at age 50.

Many Americans follow these guidelines, but screening potential is "unfulfilled due to lower than optimal uptake and quality issues," according to the ACS' 2023-2024 Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures report. Only 64% of women over the age of 45 have followed ACS guidelines for receiving a mammogram, and nearly 3 in 5 (59%) adults in the same age group were screened per the guidelines for colorectal cancer, according to the report.

The rural/urban divide in testing

As in other areas of health care, there are disparities along racial, geographical, and socioeconomic lines for who is getting screened and ultimately treated for various cancers.

Sivendran pointed to geographic differences and a rural/urban divide driving much of the disparity. People in rural areas may face transportation challenges and need help getting to their medical appointments. They also need access to more specialized services or cutting-edge technologies often pioneered at large research institutions in urban settings.

Health care providers, governments, and nonprofit organizations have concentrated on addressing these disparities in recent years. In their Cancer Moonshot initiative first announced in 2022, President Joe Biden and first lady Jill Biden listed ensuring access to cancer screenings as their first objective. Last year, the initiative announced an additional $240 million investment to find new ways to prevent, detect, and treat cancer, including funding to develop new cancer-detection tools.

Pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies are pitching in too. Pfizer funded a $15 million initiative led by the ACS to increase access to cancer screenings, clinical trials, and patient support, with an initial focus on breast and prostate cancer in underserved communities.

"How do we make sure what ZIP code you live in doesn't determine the quality of your cancer care?" Sivendran said. "Your ZIP code shouldn't be the reason you have different outcomes."

The CDC collected screening data for males and females, and this story specifically looks at female populations in designated age ranges for breast and cervical cancers. Northwell Health and Stacker recognize not all people who are at risk of breast and cervical cancers identify as women.

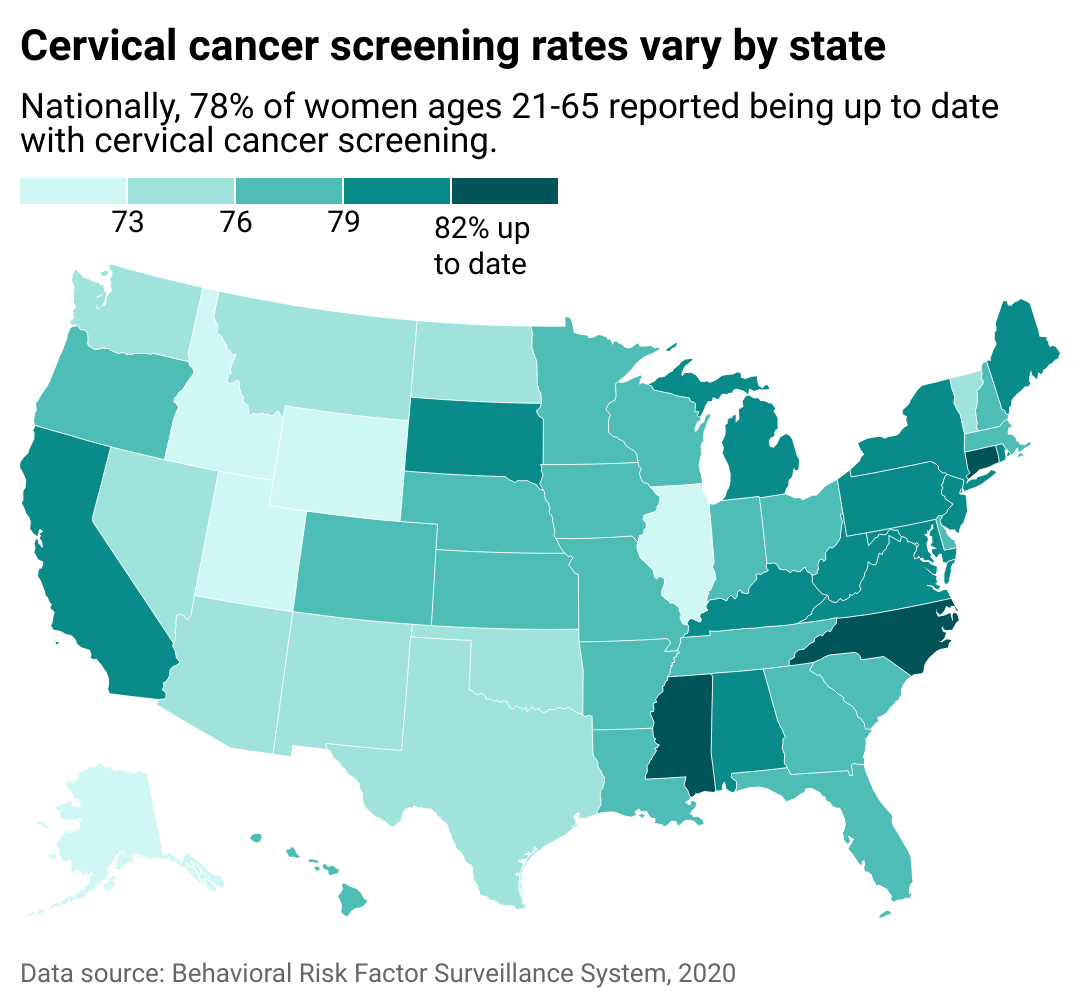

Cervical cancer

Since the mid-1970s, the cervical cancer death rate has dropped by more than half, with rates stabilizing in recent years, according to the ACS. The initial decrease is due in large part to prevention efforts and screening.

The human papillomavirus causes most cervical cancers, and the CDC recommends girls aged 11 or 12 get the HPV vaccine as a prevention measure. However, the vaccine isn't protective against all types of cervical cancer, so it is essential for women to still get screened with regular Pap tests starting at age 21.

Up-to-date screening rates vary from 90% or more in states such as South Dakota and Connecticut to as low as 79% in Alaska.

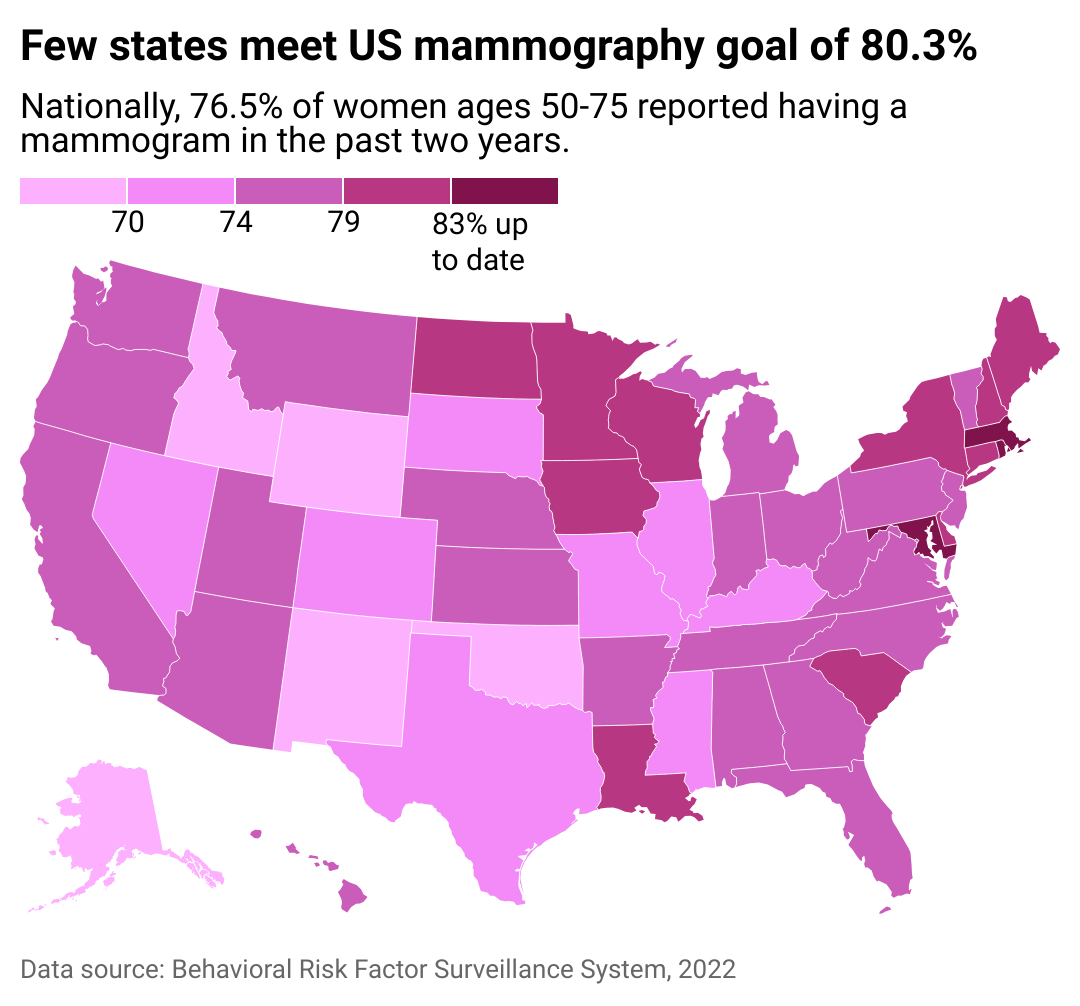

Breast cancer

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among U.S. women. The ACS reports that 1 in 8 women will be diagnosed with invasive breast cancer in their lifetime, and 1 in 39 women will die from it.

In self-reported data, Black women are more likely than white women to report being screened within the past year or two (65% for white women and 69% for Black women) for breast cancer. However, a 2021 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that Black women are less likely than white women to be given newer 3D technology for their mammograms. Medical facilities were more likely to instead give Black women 2D mammography, an older technology, even when both machines were offered in the same facility.

The 3D mammography has a higher detection rate and lower recall (false positive) compared to the older technology, according to a 2021 study published in the journal Radiology.

Despite the higher self-reported screening numbers among Black women, the long-term outcomes of a breast cancer diagnosis show a striking disparity.

"Death rates are highest among Black women, exceeding those in White women by 40% and almost 2.5 times higher than Asian/Pacific Islander (API) women, who have the lowest rates," the ACS said in its 2022-2024 Breast Cancer Facts & Figures report. "Thus, both Black and American Indian/Alaska Native women have higher mortality rates than White women despite lower incidence."

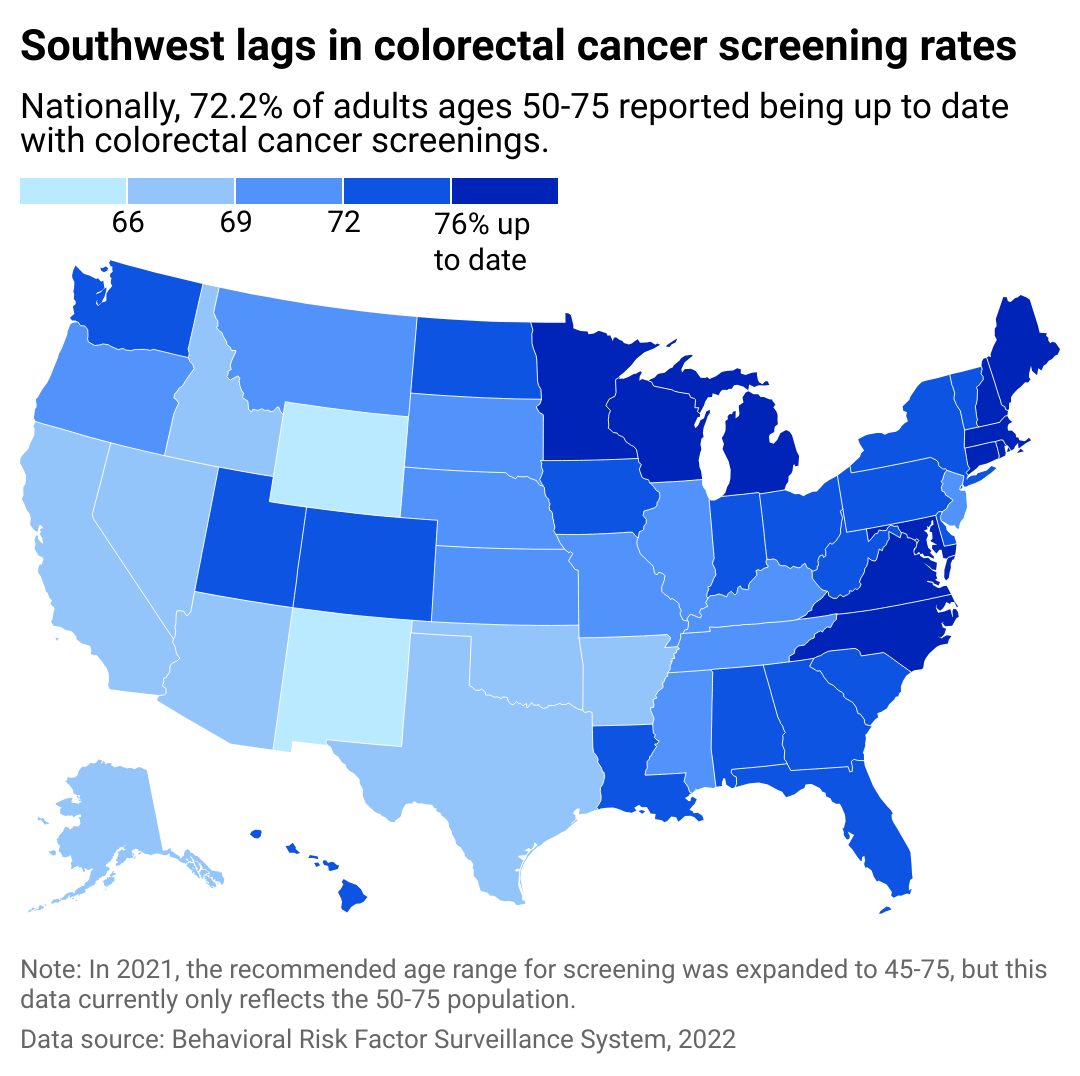

Colorectal cancer

Researchers have seen more young people diagnosed with and die from colorectal cancer. Diagnoses of people under 55 doubled from 11% in 1995 to 20% in 2019, according to the ACS.

"It's an alarming trend we are seeing," Sivendran said. "Colorectal cancer was previously the fourth leading cause of cancer death in men and women under the age of 50. It has moved to the first in men and the second in women in the span of less than two decades."

Previous guidelines recommended people get a colonoscopy at age 50, but Sivendran emphasized that once you hit your 45th birthday, you should talk to your doctor about getting a screening.

"It appears there is some shift that has happened in people born in 1960 and onwards," Sivendran said.

She added that experts are actively researching why there has been such a sudden shift, investigating population-level changes in genetics, environment, and diet as potential culprits but have yet to reach a conclusion.

Screening rates vary widely, with some states in the Great Lakes region and along the East Coast reporting higher rates and New Mexico and Wyoming as among the lowest.

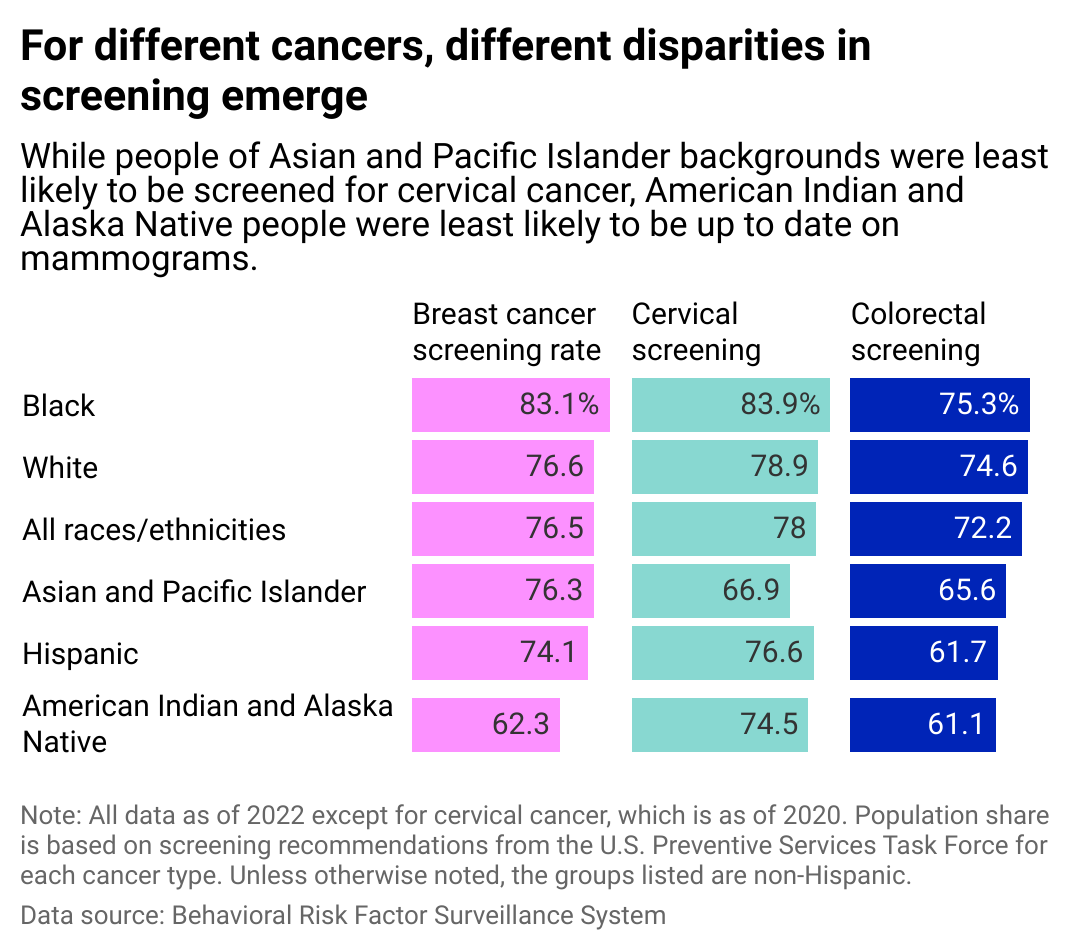

Racial disparities

This story cites data from the CDC's Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, used by the ACS and other reputable research organizations. However, the BRFSS data is collected via phone interviews with people living in the United States, and many researchers point out that self-reported data is often inaccurate and result in underestimates of disparities.

Some studies compared self-reported cervical cancer screening rates to the patient's actual health records and found that the patients overestimated their screening rate. Additionally, there was sometimes a misclassification of the individual's race.

"Despite mixed findings regarding cancer screening disparities, research suggests people of color receive later stage diagnoses for some types of cancer compared to their White counterparts," the KFF reports. "For certain cancers, disparities in stage of diagnosis despite comparable screening rates may be related to screening guidelines not accounting for earlier onset and increased age-specific cancer incidence for different groups, as well as disparities in quality of screening techniques and delays in diagnostic evaluation."

While the disparity in screening rates can be murky, we know that Black people experience worse outcomes when diagnosed: Black people have the highest death rate for most cancers, according to the ACS.

Solving this disparity will take a multipronged approach, Sivendran said. Governments and organizations can invest in infrastructure to encourage an active lifestyle, ensure that all neighborhoods have access to nutritious cancer-fighting food, provide transportation to rural patients who may need specialized services, and of course, ensure life-saving screening tests are available to all who need it.

Story editing by Ashleigh Graf. Copy editing by Paris Close.