Coral reefs: How they work, why they're in danger, and why it matters

Coral reefs: How they work, why they're in danger, and why it matters

Coral reefs are some of the world's most diverse ecosystems— even more diverse than some tropical rainforests. They offer habitat and protection for many underwater organisms and, from a purely visual standpoint, are beautiful to behold. These reefs are made up of the skeletons of coral polyps and are found all over the world. Most coral live in warm, tropical seas, but some can survive way down at the bottom of the ocean where it is dark and cold. About 25% of marine life rely on coral reefs for food, shelter, and breeding. People around the world also rely on coral reefs for food, medicine, and environmental protection like preventing coastal erosion.

The biggest coral reef is the Great Barrier Reef, which is located off the coast of Australia and is over 1,500 miles long. Unfortunately, the Great Barrier Reef is struggling with the impacts of climate change. In fact, the UNESCO World Heritage status of the Great Barrier Reef is being reconsidered because a large portion of the reef has been degraded. In a report to UNESCO, the Queensland government referred to the reef as "an icon under pressure with a deteriorating long-term outlook."

This description of the Great Barrier Reef has become apt for coral reefs all around the world, which are being threatened by overfishing, pollution, storms, diseases, predators, and rising sea temperatures due to climate change. The Earth has already lost 27% of the world's live coral, and conditions are not improving. Using data from a range of sources, including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Conservation International, the Coral Reef Alliance, and others, Stacker compiled a list of things readers should know about coral reefs. This article reveals how coral reefs work, why they're in danger, and why it matters.

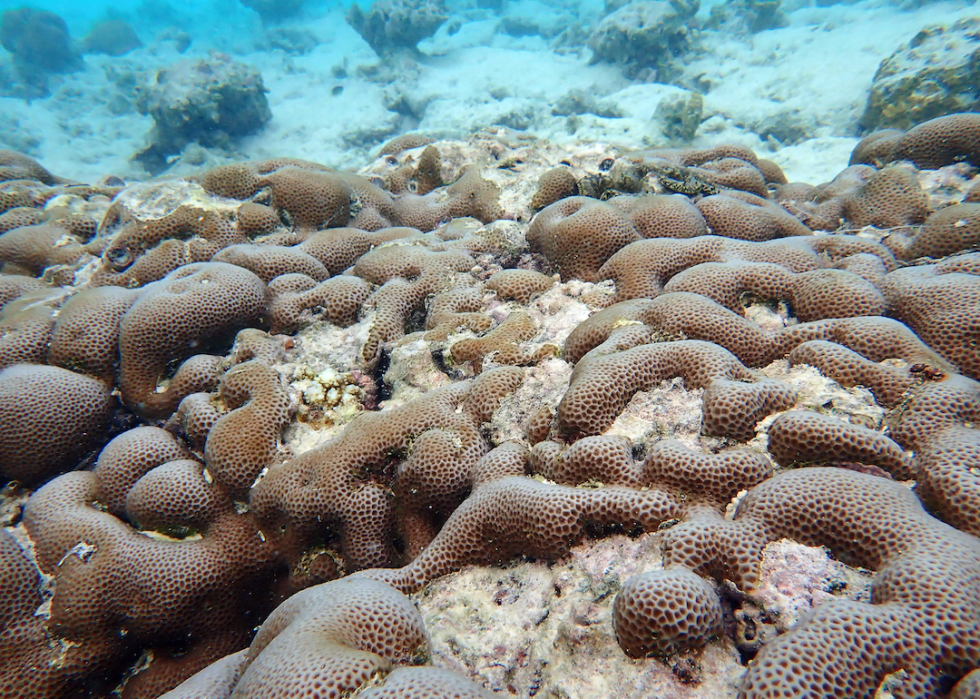

Coral reefs are made of skeletons

Corals comprise of the skeletons of generations of hard corals. When an individual coral polyp dies, it leaves its skeleton behind, and the next generation grows on that skeleton. Then fish, such as parrotfish and sea urchins, along with other organisms break these skeletons down into smaller pieces, which end up in the gaps of the reef.

[Pictured: Macro image of coral polyps.]

Coral reefs grow by latching onto rocks

Reefs are created and grow when coral larvae latch onto submerged rocks and other hard surfaces in the ocean. The coral polyps then secrete skeletons, which are made from calcium carbonate. These skeletons protect coral from predators and also provide a surface to which the coral polyps attach themselves, thus growing the reef.

[Pictured: A bommie reef in the Egyptian Red Sea.]

Corals (generally) like it warm

Warm water is best for coral reef growth, and most thrive between 70 and 85 degrees Fahrenheit. They prefer to be close to the surface where sunlight can come through. There are corals in the ocean that are as deep as 300 feet, but in general, reef-building corals do not grow well below 60-90 feet.

[Pictured: Reef-building coral colonies grow on the edge of a low-lying island just off of Raiatea and Tahaa in French Polynesia.]

Today’s coral reefs are pretty young

While the geological record shows that the predecessors of today's coral reefs were formed at least 240 million years ago, most of the coral reefs we see today are between 5,000 and 10,000 years old. And size doesn't necessarily indicate how old a reef is.

[Pictured: A Ph.D. student conducts research on the coral reefs of the Gulf of Eilat at the Interuniversity Institute for Marine Sciences.]

Coral reefs come in different shapes and sizes

There are many kinds of coral reef formations, which scientists generally split into four groups: atolls, barrier reefs, fringing reefs, and patch reefs. Atolls are rings of coral that create lagoons, and they are usually located out in the sea. Barrier reefs grow near the coastline and are separated from the shore by wide lagoons. Fringing reefs also grow near the coasts but are separated from the shore by narrow lagoons, and patch reefs grow in isolated "patches" and are small, usually growing up from the bottom of an island platform.

[Pictured: Aerial views of The Great Barrier Reef in Cairns, Australia captured on Aug. 7, 2009.]

Coral reefs are very biodiverse

Coral reefs are thought by many scientists to have the highest level of biodiversity of any ecosystem on Earth, including tropical rainforests. Although they only occupy less than 1% of the ocean, coral reefs are home to over a quarter of all marine life.

[Pictured: A sea turtle swims in the Ras Mohammed protection area near Sharm el-Sheikh in Egypt.]

Coral reefs cultivate symbiotic relationships

Many reef-building corals contain photosynthetic algae called zooxanthellae in their tissue. The corals and the algae have a symbiotic relationship, meaning that the coral provides the algae with the compounds needed for photosynthesis along with a protected environment. In exchange, the algae produce oxygen and help the coral dispose of its waste. This mutualistic relationship recycles nutrients in nutrient-deficient tropical waters.

[Pictured: Bright sunlight shines on a fragile colony of staghorn coral.]

Coral reefs provide food

The fish that depend on coral reefs provide food for over a billion people around the world. They are vital to the world's fisheries and form the nurseries for approximately a quarter of the fish in the ocean. If properly managed, reefs can provide up to 15 tons of fish and seafood per 247 acres each year. The NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service estimates that in the United States, the annual commercial value of coral reefs to national fisheries is over $100 million.

[Pictured: A Rusty Parrotfish (Scarus ferrugineus) feeds on algae.]

Coral reefs help make medicine

Some species that live in coral ecosystems produce chemical compounds useful in pharmaceuticals. Some of these medicines are being developed to treat cancer, arthritis, asthma, bacterial infections, heart, and other diseases. This potential has led coral ecosystems to be dubbed by some as the "medicine cabinets of the 21st century."

[Pictured: A coral sample in a test tube is pictured at the National Sequencing Center (Genoscope) in Evry, France.]

Coral reefs create and protect land

Long after volcanic islands sink back into the sea, the atoll islands created by coral growth and other reef-associated organisms can remain above the ocean's surface. In addition, coral reefs can protect adjacent land from storms and tsunamis and prevent coastline erosion.

[Pictured: An aerial view of Lady Elliot Island, Australia photographed in 2012.]

Much tourism relies on coral reefs

Millions of scuba divers and snorkelers visit coral reefs each year, and more people visit the beaches protected by the reefs. This tourism brings billions of dollars into local economies in reef regions through fishing trips, boat trips, and diving tours, along with associated hotels, restaurants, shopping, and other tourism-related business. One estimate places the value of coral-reef based recreation and tourism at $9.6 billion.

[Pictured: A free diver swims over a vivid coral reef in the Red Sea, Egypt.]

But coral reefs also struggle with too much tourism

While tourism might need coral reefs, coral reefs are suffering some unintended consequences of tourism. For example, scuba divers and snorkelers often inadvertently touch, pollute, or damage parts of coral reefs, which stress the corals and can lead to coral bleaching, which can eventually kill the coral.

[Pictured: Snorkelers on Jackson Reef in the Straits of Tiran, Egypt.]

So what is coral bleaching?

When corals get stressed by changes in temperature and nutrients or an influx of pollutants or irritants, they get rid of their symbiotic algae and turn white. Without the algae, the coral loses its primary source of food, making it more vulnerable to diseases that can eventually lead to death.

[Pictured: A bleached coral colony.]

Pollution and sedimentation hurt reefs

As humans continue to develop beachfront areas, the resulting deposits of pollutants and sediments into the water have become a primary stressor for coral species. The sediments deposited onto reefs can suffocate the coral, interfering with feeding, growth, and reproduction. Pollutants also impact coral reproduction and growth and can lead to coral bleaching.

[Pictured: Fish pass over a coral reef at Hanauma Bay in Honolulu, Hawaii.]

Overfishing and coral harvesting damage reefs as well

Increased demand for fish has led to overfishing, which can change the structure of the food chain and cause unintended ecosystem consequences, such as algal overgrowth. In addition, the use of explosives to kill fish can cause physical damage to the corals. There is also a practice of harvesting the coral itself for aquariums, jewelry, and other items that destroys the reef habitat.

[Pictured: Indonesian workers transport caught tuna in Denpasar, on Bali island.]

Rising ocean temperatures are killing coral

We can't talk about the threats facing coral species and coral reefs without mentioning climate change. As atmospheric temperatures rise, seawater temperatures do as well. This rise in temperature leads to coral bleaching because the coral loses its food-producing algae, leaving just the white calcium carbonate structure, which makes the coral more susceptible to diseases.

[Pictured: Dead and dying coral lies on the sea floor near Male, Maldives in this image taken in December 2019.]

Ocean acidification is also killing coral

Along with rising temperatures, climate change has lowered the pH of oceans, making them more acidic. This is because the amount of carbon dioxide in the ocean increases as much as it does in the atmosphere. When carbon dioxide enters the ocean, it reacts with seawater to form carbonic acid, making the ocean more acidic. This increased acidity slows coral and reef growth, and when acidification is especially severe, the coral skeletons making up the reefs can dissolve.

[Pictured: French scientist Sylain Agostini checks seawater on the deck of the French research schooner Tara in March 2017 near Shikinejima Island, Japan.]

Mass bleaching events becoming more common

There have been more mass bleaching events, occurrences of coral bleaching taking place over hundreds of miles, within the last decade. In 2016, over 85% of the northern and far northern areas of the Great Barrier Reef experienced bleaching, and 29% of the reef's shallow-water corals died. During that same time, bleaching also occurred in much of the Western Indian Ocean. And between 2014 and 2017, the longest and most destructive mass bleaching event took place, with over 75% of global coral reefs experiencing bleaching-level high temperatures.

[Pictured: Dead coral lies on the seabed near Male, Maldives in December 2019.]

What can be done?

According to the IUCN, the only hope for saving global reefs is lowering emissions. Limiting the rise in temperatures to 1.5° Celsius, as outlined in the Paris Agreement on climate change, would likely lead to a decrease in atmospheric carbon concentrations, which would then also lead to oceans becoming less acidic and would prevent seawater temperatures from going up. The IUCN Issues Brief on coral reefs says that this reduction in emissions would provide the "only chance for the survival of coral reefs globally," and that "other measures alone, such as addressing local pollution and destructive fishing practices, cannot save coral reefs without stabilized greenhouse gas emissions."

[Pictured: Steam and exhaust rise from industrial facilities in Germany.]

So how are we doing?

At this moment, the world is not on track to meet the goals set out in the Paris Agreement on climate change. So scientists are looking to other methods to save the reefs, such as coral transplants, where they take fragments of coral that have survived bleaching, grow them separately, and attach them onto the reefs. Other scientists are raising coral larvae in labs and then using them to restore damaged patches of the Great Barrier Reef. But these projects take time and money, and if temperatures continue to rise, resilience will become essential. Some researchers are looking at coral species that are already well-suited to high temperatures to learn about the physical and behavioral characteristics that help these species survive.

You may also like: Countries exporting the most endangered species to America