The chain reaction car crash: Who's to blame?

The chain reaction car crash: Who’s to blame?

A multicar pile-up: It’s the stuff of highway horror stories. Twisted metal, flashing lights, and a catastrophic domino effect that leaves a dozen drivers staring at each other, all asking the same volatile question: “Who started it?” And because fault directly determines which auto insurance policy pays for the damage, the stakes for getting it right couldn’t be higher.

In these chaotic scenes, human instinct is to point the finger at the very first car to brake or the very last car to crash. But in the eyes of the law, the answer is rarely that simple. A chain-reaction accident is a complex legal and investigative puzzle where liability is determined not just by the sequence of events, but by the principle of negligence.

This isn’t just about a driver failing to stop; it’s a deep dive into driving science, legal causation, and the ultimate responsibility we hold when operating a machine at high speed. CheapInsurance.com unravels the chain of fault and figures out who is truly to blame.

The Dominos: Understanding the Core Crash Scenario

Before discussing blame, the event must be defined. The most common type of chain-reaction accident is the “three-car pile-up” scenario, where Driver A stops or slows suddenly, Driver B hits Driver A, and then Driver C hits Driver B.

In most simple, nose-to-tail accidents, the rearmost driver (Driver C, in this case) is presumed to be at fault for the impact with the car immediately in front of them (Driver B). Why? Because of a non-negotiable legal duty: the obligation to maintain a safe following distance.

The Unforgiving Science of Following Distance

The law in most jurisdictions, whether phrased as the “assured clear distance ahead” rule or simply “maintain a proper following distance,” is the first line of defense against being the rearmost person in a pile-up.

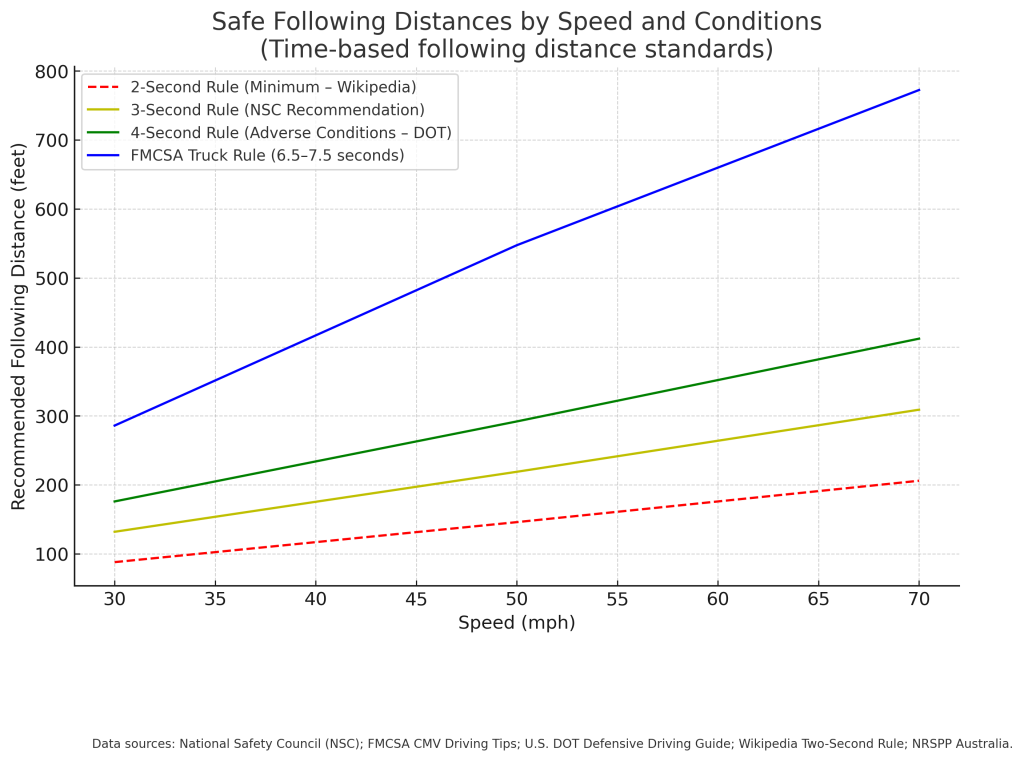

- The two-second rule: This common standard ensures there is enough time to perceive a hazard and fully react.

- The science of reaction time: The time it takes a driver to see a hazard and physically move their foot to the brake pedal is not zero. This reaction time, combined with the deceleration time of the vehicle, is what determines the safe distance.

If a driver is following too closely and strikes the car in front of them, they are generally considered negligent for that collision, regardless of why the car in front of them stopped. The driver’s negligence is a direct, immediate cause of that impact.

The Great Legal Battle: Proximate Cause vs. Negligence

The real complexity in a chain-reaction crash begins when the initial collision causes the second, third, and subsequent collisions. This is where the powerful, often elusive legal concept of proximate cause enters the courtroom.

Proximate cause is the idea that a negligent action must be “closely enough related” to the resulting damages to justify assigning legal responsibility. Think of it as a “normative strainer” that prevents one negligent driver from being held liable for every single consequence that ripples out into the world.

Scenario 1: The Single Chain of Negligence

In this scenario, Driver A slams into a sudden, unexpected roadblock. Driver B, following too closely, hits A. Then, Driver C, also following too closely, hits B. In many states, the finding may be that Driver B is responsible for the damage to A, and Driver C is responsible for the damage to B (and potentially B’s damage to A). The fault is apportioned between the vehicles that collided directly due to their failure to maintain distance.

Scenario 2: The Initial Negligent Act

This is the scenario that breaks the simple “rearmost driver” rule. Imagine this:

- Driver A is traveling at 90 mph in a blinding fog, a clearly negligent act for the conditions.

- Driver A slams into the median barrier.

- Driver B, C, D, and E all crash into the resulting debris and stopped vehicles, creating a massive, interconnected pile-up.

In this case, an investigator or jury may find that Driver A’s initial, reckless act (the excessive speed and failure to adjust to conditions) was the proximate cause of all the subsequent collisions. Driver A created a hazard so profound, sudden, and dangerous that the other drivers’ inability to stop even if they were following the two-second rule was a foreseeable consequence of the initial negligence.

The key question becomes: Did the initial negligence create an independent and unavoidable danger that made all subsequent crashes virtually inevitable? If the answer is yes, the initial driver shoulders a disproportionately high or even sole percentage of the fault for the entire catastrophe.

The Mechanics of Apportioning Fault

Modern legal systems, particularly in states that use comparative fault rules, do not require a plaintiff to prove which defendant caused which specific injury when it’s an indivisible injury (like whiplash) caused by successive negligent acts. Instead, they use a process of apportionment:

- Police reports (the first draft of history): Officers assign an initial fault percentage, but this is often overturned in court or by insurance adjusters.

- Accident reconstruction specialists: They use physics, skid marks, and crush analysis to calculate speeds, stopping distances, and the force of each impact. This data is critical for proving who was following too closely.

- The indivisible injury doctrine: If a victim in a multicar crash has injuries that cannot be rationally apportioned to a specific impact (a broken leg from the first crash and whiplash from the third), multiple negligent drivers may be held jointly and severally liable for the full extent of the victim’s damages.

The Bottom Line: Personal Responsibility Reigns

So, who is really to blame for the chain-reaction crash?

In the end, it’s often a combination of drivers who failed in their individual duty of care. While the first person to crash may be the “but for” cause of the pile-up, the second, third, and fourth drivers often bear the fault for their own separate impacts because they failed to maintain a safe stopping distance.

The ultimate lesson of the chain-reaction crash is not about blaming a single trigger; it’s about personal vigilance. The most effective defense against being at fault in a pile-up for drivers is not to hope for the car behind them to be attentive, but to ensure that their own following distance and that precious gap of asphalt is wide enough for the driver to stop, regardless of what the driver in front of you does. That safe space is the ultimate shield of responsibility.

This story was produced by CheapInsurance.com and reviewed and distributed by Stacker.