The share of seniors in Henry County, Tennessee with Alzheimer's

The share of seniors in Henry County, Tennessee with Alzheimer's

An estimated 10.7% of Henry County's 65+ population has Alzheimer's disease, according to new estimates released in 2023 by the Alzheimer's Association. That compares to 10.9% statewide, and ranks #26 of 95 counties in Tennessee included in the data. Locally, it means about 800 people have Alzheimer's in Henry County.

Alzheimer's disease afflicts an estimated 6.7 million Americans, and that number is only growing. Without a breakthrough in prevention—or a cure—medical professionals believe the volume of diagnoses could double by 2060. Researchers hope the new state- and county-level estimates will help regional public health officials better treat Alzheimer's patients, develop localized care plans, and budget for care—particularly as new treatments come at a cost.

Alzheimer's is the most common form of dementia, and among the top 10 causes of death in the U.S. These deaths are increasing as deaths from other health-related causes, including heart disease and stroke, are on the decline. With Alzheimer's, the brain shrinks, brain cells die, and peoples' memory and language centers fail. As the disease advances, the loss of brain function leads to dehydration, malnutrition, infection, and ultimately death.

Progress on finding a cure or effective treatment for Alzheimer's has been slow, as medical professionals still don't know what causes it. But earlier this year, the Food and Drug Administration fully greenlit the first drug proven to effectively treat the disease: lecanemab (sold under the brand name Leqembi), created by Eisai Inc. and Biogen. Earlier treatments only addressed symptoms of Alzheimer's, while lecanemab treats the early stages of the disease itself and slows its progression.

The drug costs $26,500 annually and is partially covered by Medicare if a patient's medical team participates in a registry to track the drug's outcomes. Those high costs could keep the treatment out of reach for low-income Americans, who already have higher odds of developing Alzheimer's, studies have shown.

Nearly all Alzheimer's patients are on government insurance, and estimates show that Medicare could spend $2 billion to $5 billion annually on lecanemab and related care. That's not much compared to the $345 billion that Alzheimer's and other dementias cost in 2023, including nursing home stays, symptom management medications, and other care for those with the disease. Without medical advancements, the Alzheimer's Association expects those costs could rise to nearly $1 trillion by 2050. If lecanemab and similar drugs can slow progression in even half of mild Alzheimer's patients, one study from the University of Chicago estimates Americans would save $212 billion to over $1 trillion in care-related costs over the next decade.

Having a treatment to slow the progression of Alzheimer's also creates more urgency to diagnose the disease sooner to retain more brain function. Warning signs for the disease include disruptive memory loss, difficulty with familiar tasks, worsening judgment, and changes in mood and personality.

The U.S. has a shortage of specialists in elder and memory-related medicine and nurses providing care at nursing homes and assisted-living facilities. In regions with high rates of Alzheimer's, these shortages could be particularly catastrophic within the current models of care.

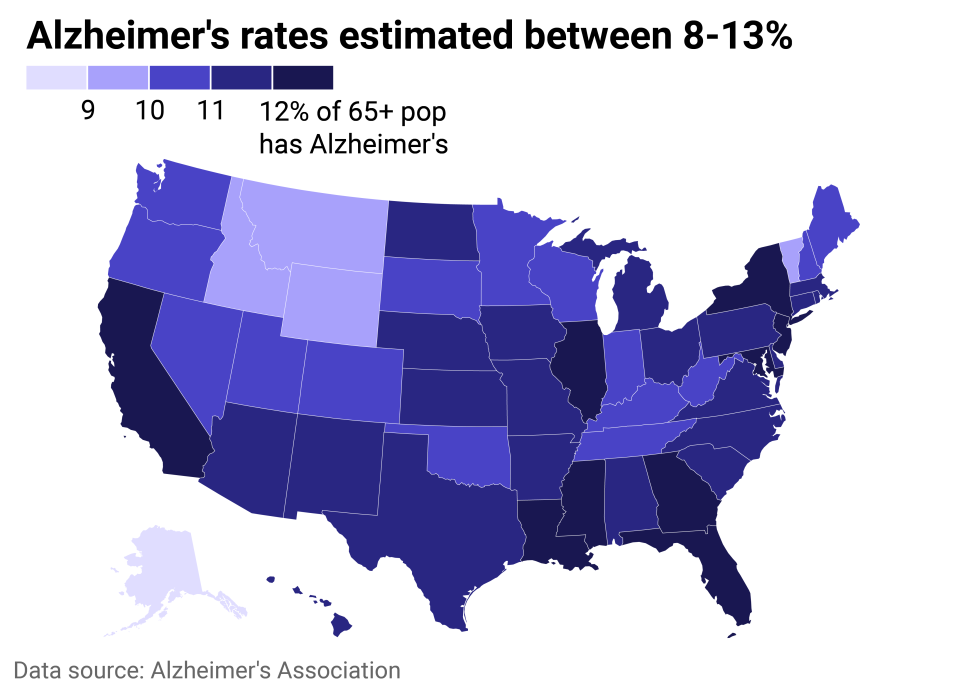

In a national analysis to see areas most at risk, Stacker mapped states by the share of the 65+ population estimated to have Alzheimer's disease, using data released by the Alzheimer's Association in July 2023.

Alzheimer's rates by state

State and detailed county-level estimates show vast disparities in the prevalence of Alzheimer's disease based on racial and socioeconomic factors. Older Americans, women, Black and Hispanic Americans, and those with lower education levels are at higher risk for developing Alzheimer's dementia, according to data from the Chicago Health and Aging Project, on which these estimates were based.

The East and Southeast regions of the U.S. were estimated to have the highest prevalence of Alzheimer's, particularly Maryland, New York, Florida, Mississippi, and Louisiana. In Maryland, nearly 30% of residents are Black, and a slightly higher share of the population is 85+ years old compared to national numbers—substantial risk factors that earn it the #1 spot. In addition to a high prevalence of the disease, Mississippi has the highest Alzheimer's mortality rate, largely due to having the worst-quality health care system in the country, Time reported.

Some of the most afflicted counties are home to Black and Hispanic populations in the South, low-income populations in Appalachia, and older adults in Florida, according to Time. Other studies have found that people in rural areas tend to be underdiagnosed or diagnosed in later stages of dementia, delaying or preventing potential treatments.

Alzheimer's Association volunteers have been using the data to advocate for public policy priorities with elected officials, the association's senior director of government affairs in New York, Bill Gustafson, told Stacker via email.

Advocates in New York recently utilized the state and county data to advocate for more resources for the Alzheimer's Community Assistance Program and the Special Needs Assisted Living Voucher Demonstration Program for Persons with Dementia. The state of New York budgets $26 million annually for services for Alzheimer's patients and announced new funding in September 2023 to focus on high-risk, rural, and historically underserved communities.

"This data is a tool to help the Alzheimer's Association demonstrate the public health crisis the disease poses for the state and, with that knowledge, urge our elected officials to support dementia-specific policy to address said crisis," Gustafson said.

Beyond medicine, doctors and researchers are evolving patient care for those with Alzheimer's, as well. One French facility creates autonomy for patients in a village-like setting, aiming to create normalcy, improve life quality, and reduce stress and depression. As treatments progress, the U.S. federal government is testing a new payment program for dementia care providers, aiming to delay nursing home stays.

Between advancing medicines, treatments, and databases, as well as shortages of caregivers and medical professionals in the field, change is on the horizon for Alzheimer's care in the U.S. and beyond.

This story features data reporting and writing by Paxtyn Merten and is part of a series utilizing data automation across 3,100 counties.